Polyketide synthase

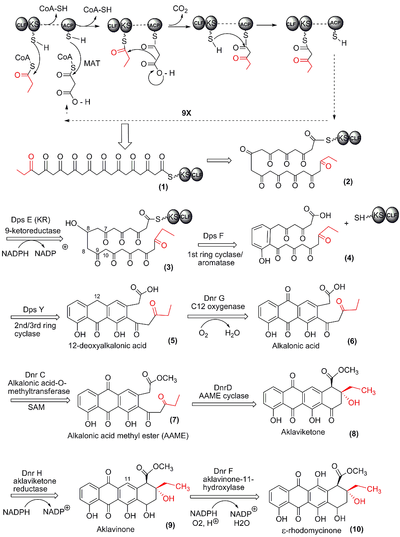

Polyketide synthases (PKSs) are a family of multi-domain enzymes or enzyme complexes that produce polyketides, a large class of secondary metabolites, in bacteria, fungi, plants, and a few animal lineages. The biosyntheses of polyketides share striking similarities with fatty acid biosynthesis.[1][2]

The PKS genes for a certain polyketide are usually organized in one operon in bacteria and in gene clusters in eukaryotes.

Classification

PKSs can be classified into three groups:

- Type I polyketide synthases are large, highly modular proteins.

- Type II polyketide synthases are aggregates of monofunctional proteins.

- Type III polyketide synthases do not use ACP domains.

Type I PKSs are further subdivided:

- Iterative PKSs reuse domains in a cyclic fashion.

- Modular PKSs contain a sequence of separate modules and do not repeat domains (with the exception of trans-AT domains).

Iterative PKSs (IPKSs) can be still further subdivided:

- NR-PKSs — non-reducing PKSs, the products of which are true polyketides

- PR-PKSs — partially reducing PKSs

- FR-PKSs — fully reducing PKSs, the products of which are fatty acid derivatives

Modules and domains

Each type I polyketide-synthase module consists of several domains with defined functions, separated by short spacer regions. The order of modules and domains of a complete polyketide-synthase is as follows (in the order N-terminus to C-terminus):

- Starting or loading module: AT-ACP-

- Elongation or extending modules: -KS-AT-[DH-ER-KR]-ACP-

- Termination or releasing module: -TE

Domains:

- AT: Acyltransferase

- ACP: Acyl carrier protein with an SH group on the cofactor, a serine-attached 4'-phosphopantetheine

- KS: Keto-synthase with an SH group on a cysteine side-chain

- KR: Ketoreductase

- DH: Dehydratase

- ER: Enoylreductase

- MT: Methyltransferase O- or C- (α or β)

- SH: Sulfhydrolase

- TE: Thioesterase

The polyketide chain and the starter groups are bound with their carboxy functional group to the SH groups of the ACP and the KS domain through a thioester linkage: R-C(=O)OH + HS-protein <=> R-C(=O)S-protein + H2O.

Stages

The growing chain is handed over from one thiol group to the next by trans-acylations and is released at the end by hydrolysis or by cyclization (alcoholysis or aminolysis).

Starting stage:

- The starter group, usually acetyl-CoA or malonyl-CoA, is loaded onto the ACP domain of the starter module catalyzed by the starter module's AT domain.

Elongation stages:

- The polyketide chain is handed over from the ACP domain of the previous module to the KS domain of the current module, catalyzed by the KS domain.

- The elongation group, usually malonyl-CoA or methylmalonyl-CoA, is loaded onto the current ACP domain catalyzed by the current AT domain.

- The ACP-bound elongation group reacts in a Claisen condensation with the KS-bound polyketide chain under CO2 evolution, leaving a free KS domain and an ACP-bound elongated polyketide chain. The reaction takes place at the KSn-bound end of the chain, so that the chain moves out one position and the elongation group becomes the new bound group.

- Optionally, the fragment of the polyketide chain can be altered stepwise by additional domains. The KR (keto-reductase) domain reduces the β-keto group to a β-hydroxy group, the DH (dehydratase) domain splits off H2O, resulting in the α-β-unsaturated alkene, and the ER (enoyl-reductase) domain reduces the α-β-double-bond to a single-bond. It is important to note that these modification domains actually affect the previous addition to the chain (i.e. the group added in the previous module), not the component recruited to the ACP domain of the module containing the modification domain.

- This cycle is repeated for each elongation module.

Termination stage:

- The TE (thio-esterase) domain hydrolyzes the completed polyketide chain from the ACP-domain of the previous module.

Pharmacological relevance

Polyketide synthases are an important source of naturally occurring small molecules used for chemotherapy.[3] For example, many of the commonly used antibiotics, such as tetracycline and macrolides, are produced by polyketide synthases. Other industrially important polyketides are sirolimus (immunosuppressant), erythromycin (antibiotic), lovastatin (anticholesterol drug), and epothilone B (anticancer drug).[4]

Ecological significance

Only about 1% of all known molecules are natural products, yet it has been recognized that almost two thirds of all drugs currently in use are at least in part derived from a natural source.[5] This bias is commonly explained with the argument that natural products have co-evolved in the environment for long time periods and have therefore been pre-selected for active structures. Polyketide synthase products include lipids with antibiotic, antifungal, antitumor, and predator-defense properties; however, many of the polyketide synthase pathways that bacteria, fungi and plants commonly use have not yet been characterized.[6][7] Methods for the detection of novel polyketide synthase pathways in the environment have therefore been developed. Molecular evidence supports the notion that many novel polyketides remain to be discovered from bacterial sources.[8][9]

See also

References

- ↑ Khosla, C.; Gokhale, R. S.; Jacobsen, J. R.; Cane, D. E. (1999). "Tolerance and Specificity of Polyketide Synthases". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 68: 219–253. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.219. PMID 10872449.

- ↑ Jenke-Kodama, H.; Sandmann, A.; Müller, R.; Dittmann, E. (2005). "Evolutionary Implications of Bacterial Polyketide Synthases". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (10): 2027–2039. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi193. PMID 15958783.

- ↑ Koehn, F. E.; Carter, G. T. (2005). "The evolving role of natural products in drug discovery". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 4 (3): 206–220. doi:10.1038/nrd1657. PMID 15729362.

- ↑ Wawrik, B.; Kerkhof, L.; Zylstra, G. J.; Kukor, J. J. (2005). "Identification of Unique Type II Polyketide Synthase Genes in Soil". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 71 (5): 2232–2238. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.5.2232-2238.2005. PMC 1087561

. PMID 15870305.

. PMID 15870305. - ↑ Von Nussbaum, F.; Brands, M.; Hinzen, B.; Weigand, S.; Häbich, D. (2006). "Antibacterial Natural Products in Medicinal Chemistry—Exodus or Revival?". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 45 (31): 5072–5129. doi:10.1002/anie.200600350. PMID 16881035.

- ↑ Castoe, T. A.; Stephens, T.; Noonan, B. P.; Calestani, C. (2007). "A novel group of type I polyketide synthases (PKS) in animals and the complex phylogenomics of PKSs". Gene. 392 (1–2): 47–58. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.11.005. PMID 17207587.

- ↑ Ridley, C. P.; Lee, H. Y.; Khosla, C. (2008). "Chemical Ecology Special Feature: Evolution of polyketide synthases in bacteria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (12): 4595–4600. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710107105. PMC 2290765

. PMID 18250311.

. PMID 18250311. - ↑ Metsä-Ketelä, M.; Salo, V.; Halo, L.; Hautala, A.; Hakala, J.; Mäntsälä, P.; Ylihonko, K. (1999). "An efficient approach for screening minimal PKS genes from Streptomyces". FEMS microbiology letters. 180 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(99)00453-X. PMID 10547437.

- ↑ Wawrik, B.; Kutliev, D.; Abdivasievna, U. A.; Kukor, J. J.; Zylstra, G. J.; Kerkhof, L. (2007). "Biogeography of Actinomycete Communities and Type II Polyketide Synthase Genes in Soils Collected in New Jersey and Central Asia". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 73 (9): 2982–2989. doi:10.1128/AEM.02611-06. PMC 1892886

. PMID 17337547.

. PMID 17337547.

External links

- Polyketide synthases at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)