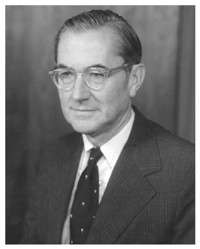

William Colby

| William Colby | |

|---|---|

| |

| Director of Central Intelligence | |

|

In office September 4, 1973 – January 30, 1976 | |

| President |

Richard Nixon Gerald Ford |

| Deputy | Vernon A. Walters |

| Preceded by | James R. Schlesinger |

| Succeeded by | George H. W. Bush |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Egan Colby January 4, 1920 St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died |

April 27, 1996 (aged 76) Rock Point, Maryland, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) |

Barbara Heinzen (1945–1984) Sally Shelton (1984–1996) |

| Children | 5 (with Heinzen) |

| Alma mater |

Princeton University Columbia University |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

William Egan Colby (January 4, 1920 – April 27, 1996) spent a career in intelligence for the United States, culminating in holding the post of the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) from September 1973 to January 1976.

During World War II Colby served with the Office of Strategic Services. After the war he joined the newly created Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Before and during the Vietnam War, Colby served as chief of station in Saigon, chief of the CIA's Far East Division, and head of the Civil Operations and Rural Development effort, as well as overseeing the Phoenix Program. After Vietnam, Colby became director of central intelligence and during his tenure, under intense pressure from the United States Congress and the media, adopted a policy of relative openness about U.S. intelligence activities to the Senate Church Committee and House Pike Committee. Colby served as DCI under President Richard Nixon and President Gerald Ford and was replaced with future president George H.W. Bush on January 30, 1976.

Early life and family

William Egan Colby was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, in 1920. His father, Elbridge Colby, who came from a New England family with a history of military and public service, was a professor of English, an author, and a military officer who served in the Army and in university positions in Tientsin, China; Georgia; Vermont; and Washington, D.C. Though a career officer, Elbridge Colby's professional pursuits focused less on strictly military activities and more on intellectual and scholarly contributions to military and literary subjects. Elbridge's father, Charles Colby, had been a professor of chemistry at Columbia University but had died prematurely, leaving his family largely without money. William's mother, Margaret Egan, was from an Irish family in St. Paul active in business and Democratic politics. With his Army father, William Colby had a peripatetic upbringing before attending public high school in Burlington, Vermont, and then Princeton University, graduating in 1940 and entering Columbia Law School the following year. Colby recounted that he took from his parents a desire to serve and a commitment to liberal politics, Catholicism, and independence, exemplified by his father's career-damaging protest in The Nation magazine regarding the lenient treatment of a white Georgian who had murdered a black U.S. soldier also based at Ft. Benning.[1][2]

Colby was for most of his life a staunch Roman Catholic.[3] He was often referred to as "the warrior–priest". He married Barbara Heinzen (1920-2015) in 1945 and they had five children. The Catholic Church played a "central role" in the family's life, with Colby's two daughters receiving their First Communion at St. Peter's Basilica.[4] In 1984, he divorced Barbara and married Democratic diplomat Sally Shelton-Colby.

Career

Office of Strategic Services

Following his first year at Columbia, in 1941 Colby volunteered for active duty with the United States Army and served with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)N as a "Jedburgh", or special operator, trained to work with resistance forces in occupied Europe to harass German and Axis forces. During World War II, he parachuted behind enemy lines twice and earned the Silver Star as well as commendations from Norway, France, and Great Britain. In his first mission he deployed to France as a Jedburgh commanding Team BRUCE, in mid-August 1944, and operated with the Maquis until he joined up with Allied forces later that fall. In April 1945, he led the NORSO Group into Norway on a sabotage mission to destroy railway lines, in an effort to tie down German forces in Norway from reinforcing the final defense of Germany.[5]

After the war, Colby graduated from Columbia Law School and then briefly practiced law in William J. Donovan's New York firm. Bored by the practice of law and inspired by his liberal beliefs, he moved to Washington to work for the National Labor Relations Board.

Central Intelligence Agency

.gif)

Shortly thereafter, an OSS friend offered him a job at the CIA, and Colby accepted. Colby spent the next 12 years in the field, first in Stockholm, Sweden. There, he helped set up the stay-behind networks of Operation Gladio, a covert paramilitary organization organized by the CIA to make any Soviet occupation more difficult, as he later described in his memoirs.[6]

Colby then spent much of the 1950s based in Rome, under cover as a State Department officer,[5] where he led the Agency's covert political operations campaign to support anti-Communist parties in their electoral contests against left wing, Soviet Union–associated parties. The Christian Democrats and allied parties won several key elections in the 1950s, preventing a takeover by the Communist Party. Colby was a vocal advocate within the CIA and the United States government for engaging the non-Communist left wing parties in order to create broader non-Communist coalitions capable of governing fractious Italy; this position first brought him into conflict with James J. Angleton.

Vietnam

In 1959 Colby became the CIA's deputy chief and then chief of station in Saigon, South Vietnam, where he served until 1962. Tasked by CIA with supporting the government of Ngo Dinh Diem, Colby established a relationship with President Diem's family and with Ngo Ngô Đình Nhu, the president's brother, with whom Colby became close.[5] While in Vietnam, Colby focused intensively on building up Vietnamese capabilities to combat the Viet Cong insurgency in the countryside. He argued that "the key to the war in Vietnam was the war in the villages."[7] In 1962 he returned to Washington to become the deputy and then chief of CIA's Far East Division, succeeding Desmond Fitzgerald, who had been tapped to lead the Agency's efforts against Castro's Cuba. During these years Colby was deeply involved in Washington's policies in East Asia, particularly with respect to Vietnam, as well as Indonesia, Japan, Korea, and China. He was deeply critical of the decision to abandon support for Diem, and he believed this played a material part in the weakening of the South Vietnamese position in the years following.[8]

In 1968, while Colby was preparing to take up the post of chief of the Soviet Bloc Division of the Agency, President Johnson instead sent Colby back to Vietnam as deputy to Robert Komer, who had been charged with streamlining the civilian side of the American and South Vietnamese efforts against the Communists. Shortly after arriving Colby succeeded Komer as head of the U.S./South Vietnamese rural pacification effort named CORDS. Part of the effort was the controversial Phoenix Program, an initiative designed to identify and attack the "Viet Cong Infrastructure." There is considerable debate about the merits of the program, which was subject to allegations that it relied on or was complicit in assassination and torture. Colby, however, consistently insisted that such tactics were not authorized by or permitted in the program.

More broadly, along with Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker and Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) commander General Creighton Abrams, Colby was part of a leadership group that worked to apply a new approach to the war designed to focus more on pacification (winning hearts and minds) and securing the countryside as opposed to the "search and destroy" approach that had characterized General William Westmoreland's tenure as MACV commander.[9] Some, including Colby later in life, argue that this approach succeeded in reducing the Communist insurgency in South Vietnam, but that South Vietnam, without air and ground support by the United States after the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, was ultimately overwhelmed by a conventional North Vietnamese assault in 1975.[8] The CORDS model and its approach influenced U.S. strategy and thinking on counterinsurgency in the 2000s in Iraq and Afghanistan.[10]

CIA Director

Colby returned to Washington in 1971 and became executive director of CIA. After long-time DCI Richard Helms was dismissed by President Nixon in 1973, James Schlesinger assumed the helm at the Agency. A strong believer in reform of the CIA and the intelligence community more broadly, Schlesinger had written a 1971 Bureau of the Budget report outlining his views on the subject. Colby, who had had a somewhat unorthodox career in the CIA focused on political action and counterinsurgency, agreed with Schlesinger's reformist approach. Schlesinger appointed him head of the clandestine branch in early 1973. When Nixon reshuffled his agency heads and made Schlesinger secretary of defense, Colby emerged as a natural candidate for DCI—apparently on the basis of the recommendation that he was a professional who would not make waves.

Colby was known as a media-friendly CIA director.[4] His tenure as DCI, which lasted two and a half tumultuous years, was overshadowed by the Church and Pike congressional investigations into alleged U.S. intelligence malfeasance over the preceding 25 years, including 1975, the so-called Year of Intelligence. Colby cooperated, not out of a desire for a major overhaul, but in the belief that the actual scope of such misdeeds—encapsulated in the so-called Family Jewels—was not great enough to do lasting damage to the CIA's reputation. Colby also believed that the CIA had a moral and legal obligation to cooperate with the Congress and demonstrate that the CIA was accountable to the Constitution. On a more practical level, he also believed that cooperating with Congress was the only way to save the Agency from dissolution during a period of great congressional strength. This openness policy caused a major rift within the CIA ranks, with many old-line officers such as former DCI Richard Helms believing that the CIA should have resisted congressional intrusion.

Colby's time as DCI was also eventful on the world stage. Shortly after he assumed leadership, the Yom Kippur War broke out, an event that surprised not only the American intelligence agencies but also the Israelis. This intelligence surprise reportedly affected Colby's credibility with the Nixon administration. Colby participated in the National Security Council meetings that responded to apparent Soviet intentions to intervene in the war by raising the alert level of U.S. forces to DEFCON 3 and defusing the crisis. In 1975, after many years of involvement, South Vietnam fell to Communist forces in April 1975, a particularly difficult blow for Colby, who had dedicated so much of his life and career to the American effort there. Events in the arms-control field, Angola, Australia,[11] the Middle East, and elsewhere also demanded attention.

Colby also focused on internal reforms within the CIA and the intelligence community. He attempted to modernize what he believed to be some out-of-date structures and practices by disbanding the Board of National Estimates and replacing it with the National Intelligence Council.[12] In a speech from 1973 addressed to NSA employees he emphasised the role of free speech in USA and moral role of CIA as defender, not preventer of civil rights. He also mentioned a number of reforms intended to limit excessive classification of governmental information.[13]

President Ford, advised by Henry Kissinger and others concerned by Colby's controversial openness to Congress and distance from the White House, replaced Colby late in 1975 with George H.W. Bush during the so-called Halloween Massacre in which Secretary of Defense Schlesinger was also replaced (by Donald Rumsfeld). Colby was offered the position of U.S. permanent representative to NATO but turned it down.

Post-CIA career

In 1977 Colby founded a D.C. law firm—Colby, Miller & Hanes, with Marshall Miller, David Hanes, and associated lawyers, and worked on public policy issues. In consonance with his long-held liberal views, Colby became a supporter of the nuclear freeze and of reductions in military spending. He practiced law and advised various bodies on intelligence matters.

During this period he also wrote two books, both of which were memoirs of his professional life combined with discussions of history and policy. One was titled Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA; the other, on Vietnam and his long involvement with American policy there, was called Lost Victory. In the latter book, Colby argued that the U.S.–RVN counterinsurgency campaign in Vietnam had succeeded by the early 1970s and that South Vietnam could have survived had the U.S. continued to provide support after the Paris Accords. Though the topic remains open and controversial, some recent scholarship, including by Lewis "Bob" Sorley, supports Colby's arguments.

Colby also lent his expertise and knowledge, along with Oleg Kalugin, to the Activision game Spycraft: The Great Game, which was released shortly before his death. Both Colby and Kalugin played themselves in the game.

William E. Colby was a member of the National Coalition to Ban Handguns. His name appears on a note to Senator John Heinz dated July 5, 1989 as a "National Sponsor".

Death

On April 27, 1996, Colby set out from his weekend home in Rock Point, Maryland on a solo canoe trip.[14] His canoe was found the following day on a sandbar in the Wicomico River, a tributary of the Potomac, approximately a quarter mile from his home.[15] On May 6, Colby's body was found in a marshy riverbank lying facedown thirty or forty meters away from where his canoe was found.[14][16] After an autopsy, Maryland's Chief Medical Examiner John E. Smialek ruled his death to be accidental.[16] Smialek's report noted that Colby was predisposed to having a heart attack or stroke due to "severe calcified atherosclerosis" and that Colby likely "suffered a complication of this atherosclerosis which precipitated him into the cold water in a debilitated state and he succumbed to the effects of hypothermia and drowned".[17][18]

Colby's death triggered allegations that his death was due to foul play.[19][20] In his 2011 documentary The Man Nobody Knew, Colby's son Carl suggested that his father suffered from guilt due to his actions in the CIA and was tired of living, hinting at the possibility that he committed suicide.[19][20] Carl's step-mother and siblings, as well as Colby's biographer Randall Woods, criticized Carl's portrayal of William Colby, and rejected the allegation that the former CIA director killed himself as inconsistent with his character.[19][20]

Legacy

Colby was the subject of a biography, Lost Crusader, by John Prados, published in 2003. His son, Carl Colby, released a documentary on his father's professional and personal life, The Man Nobody Knew, in 2011.[5][21] In May 2013, Randall B. Woods, Distinguished Professor of History at the J. William Fulbright School at the University of Arkansas, published his biography of Colby, titled Shadow Warrior: William Egan Colby and the CIA.[22] Norwich University hosts an annual writers symposium named in his honor.[23]

Quotes

- "We disbanded our intelligence [after both world wars] and then found we needed it. Let's not go through that again. Redirect it, reduce the amount of money spent, but let's not destroy it. Because you don't know 10 years out what you're going to face."[24]

- "The more we know about each other the safer we all are." — Colby to Leonid Brezhnev

- On walking alone, unfollowed, through Red Square in 1989, after the end of the Cold War: "That was my victory parade." [25]

Bibliography

- Colby, William (1975). Intelligence and the press: Address to the Associated Press annual meeting by William E. Colby on Monday, 7 April 1975. CIA.

- Colby, William (1975). Foreign intelligence for America: Address to the Commonwealth Club of California by William E. Colby on Wednesday, 7 May 1975 in San Francisco, California. CIA (1975).

- Colby, William (1975). Director of Central Intelligence press conference: CIA Headquarters auditorium, 19 November 1975. CIA.

- Colby, William (1978). Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA (first ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-22875-0.

- Colby, William (1986). The increased role of modern intelligence: A public speech on February 21, 1986 in Taipei. AWI lectures. Asia and World Institute.

- Colby, William (1989). Lost victory: a firsthand account of America's sixteen-year involvement in Vietnam. Chicago: Contemporary Books. ISBN 0809245094. OCLC 20014837.

References

- ↑ "Justice in Georgia". The Nation. 123 (3184): 32–33. 1926-07-14.

- ↑ Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA. 1978. pp. 26–28.

- ↑ "Obituary: William Colby". The Daily Telegraph. 1996-05-07. Retrieved 2007-09-07. Archived on personal website.

- 1 2 Elliott, John (2011-11-11) Finding William Colby, The American Conservative

- 1 2 3 4 Carl Colby (director) (September 2011). The Man Nobody Knew: In Search of My Father, CIA Spymaster William Colby (Motion picture). New York City: Act 4 Entertainment. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ↑ Colby, William; Peter Forbath (1978). Honourable Men: My Life in the CIA (extract concerning Gladio stay-behind operations in Scandinavia). London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-134820-X. OCLC 16424505.

- ↑ "Interview with William Egan Colby, 1981." 07/16/1981. WGBH Media Library & Archives. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- 1 2 William E. Colby & James McCargar (1989). Lost Victory: A Firsthand Account of America's Sixteen-Year Involvement in Vietnam.

- ↑ For histories on the CIA's role in Vietnam and on the pacification effort more broadly, see foia.cia.gov

- ↑ General David Petraeus, Lieutenant General James F. Amos, and Lieutenant Colonel John A. Nagl (2008). The U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual. pp. 73–75.

- ↑ Pilger, John, A Secret Country, Vintage Books, London, 1992, ISBN 9780099152316, pp. 185, 210-11, 219, 235.

- ↑ For further information on Colby's leadership of the Intelligence Community, see cia.gov

- ↑ William H. Colby (1973). "Security in an Open Society" (PDF). NSA.

- 1 2 Weiner, Tim (May 7, 1996). "William E. Colby, 76, Head of C.I.A. in a Time of Upheaval". New York Times. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Search for ex-spymaster continues". Rome News-Tribune. 153 (103). Rome, Georgia. AP. April 30, 1996. p. 1. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- 1 2 "Autopsy: Colby collapsed before falling out of canoe". Sun-Journal. 104. Lewiston, Maine. AP. May 11, 1996. p. 5A. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ↑ Colby, Jonathan E.; Colby, Elbridge A. (December 2, 2011). "A film by the son of CIA spymaster William Colby has divided the Colby clan". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Post Mortem Examination Report, Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, State of Maryland, Report on Death of William E. Colby" (PDF). Huffington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Wilkie, Christina (December 5, 2011). "Former CIA Director's Murder Raises Questions, Divides Family". The Huffington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Shapira, Ian (November 19, 2011). "A film by the son of CIA spymaster William Colby has divided the Colby clan". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ↑ "The Man Nobody Knew". Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ Thomas, Evan (May 5, 2013). "The Gray Man". New York Times.

- ↑ The William E. Colby Military Writers Symposium, http://colby.norwich.edu/ Accessed 8/29/2013.

- ↑ "A Spymaster Assessment". Newsweek. CXVIII (23): 56. 1991-12-02.

- ↑ Randall Woods (2013). Shadow Warrior: William Egan Colby and the CIA. p. 493.

Memoirs

- Colby, William; Peter Forbath (1978). Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22875-7.

- Colby, William; James McCargar (1989). Lost Victory: A Firsthand Account of America's Sixteen-Year Involvement in Vietnam. Chicago: Contemporary Books. ISBN 0-8092-4509-4. OCLC 20014837.

Biographies

- Colby, Carl (2011). Colby: A Secret Life of a CIA Spymaster. Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute. ISBN 9781591141228. OCLC 751577970.

- Ford, Harold P. (1993). William E. Colby as Director of Central Intelligence, 1973-1976. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. Declassified official CIA history of Colby's tenure, available at nsarchive.gwu.edu

- Prados, John (2009). William Colby and the CIA: The Secret Wars of a Controversial Spymaster. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700616909. OCLC 320185462.

- Waller, Douglas C. (2015). Disciples: The World War II Spy Story of the Four OSS Men Who Later Led the CIA: Allen Dulles, Richard Helms, William Colby, William Casey. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781451693720. OCLC 911179767.

- Woods, Randall B. (2013). Shadow Warrior: William Egan Colby and the CIA. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465021949. OCLC 812081249.

Additional sources

- "William Colby: Retrospect". Central Intelligence Agency. 2007-05-08. Retrieved 2007-09-07. Evaluation of his tenure by CIA historian/official.

- Sorley, Lewis (1999). A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam. Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-100266-5.

- Garthoff, Douglas (2005). Directors of Central Intelligence as Leaders of the U.S. Intelligence Community, 1946–2005. Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 1-929667-14-0.

- "Randall B. Woods: William E. Colby and the CIA". 2011-04-29. Retrieved 2011-09-18. Talk on Colby's legacy by University of Arkansas Cold War historian Randall Woods.

- Fallaci, Oriana (1977). Interview With History. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-25223-7. Interview with William Colby

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Colby. |

- William E. Colby Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "William Colby". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- Oral History Interviews with William Colby, from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

- Coroner's Report on William E. Colby's Death

- OSS Operation RYPE / NORSO

- National Coalition to Ban Handguns Letter to Sen. John Heinz

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James R. Schlesinger |

Director of Central Intelligence 1973–1976 |

Succeeded by George H. W. Bush |