Drowning

| Drowning / near drowning | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vasily Perov: The drowned, 1867 | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

| ICD-10 | T75.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 994.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 3957 |

| MedlinePlus | 000046 |

| eMedicine | emerg/744 |

| MeSH | C23.550.260.393 |

Drowning is defined as respiratory impairment from being in or under a liquid.[1] It is further classified by outcome into: death, ongoing health problems, and no ongoing health problems.[1] Using the term near drowning to refer to those who survive is no longer recommended.[1] Drowning itself is quick and silent, although it may be preceded by distress which is more visible.[2]

Generally in the early stages of drowning very little water enters the lungs: a small amount of water entering the trachea causes a muscular spasm that seals the airway and prevents the passage of both air and water until unconsciousness occurs. This means a person drowning is unable to shout or call for help, or seek attention, as they cannot obtain enough air. The instinctive drowning response is the final set of autonomic reactions in the 20–60 seconds before sinking underwater, and to the untrained eye can look similar to calm safe behavior.[2][3] Lifeguards and other persons trained in rescue learn to recognize drowning people by watching for these movements.[2]

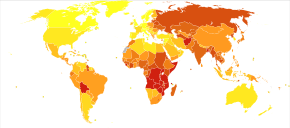

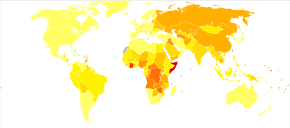

In 2013 there were about 1.7 million cases of drowning.[4] Unintentional drowning is the third leading cause of unintentional injury resulting in death worldwide. In 2013 it was estimated to have resulted in 368,000 deaths down from 545,000 deaths in 1990.[5] Of these deaths 82,000 occurred in children less than five years old.[5] It accounts for 7% of all injury related deaths (excluding those due to natural disasters), with 91% of these deaths occurring in low-income and middle-income countries.[6] Drowning occurs more frequently in males and the young.[7] The rate of drowning in populations around the world varies widely according to their access to water, the climate and the national swimming culture.

Signs and symptoms

Drowning is most often quick and unspectacular. Its media depictions as a loud, violent struggle have much more in common with distressed non-swimmers, who may well drown but have not yet begun to do so. In particular, an asphyxiating person is seldom able to call for help.[2] The instinctive drowning response covers many signs or behaviors associated with drowning or near-drowning:

- Head low in the water, mouth at water level

- Head tilted back with mouth open

- Eyes glassy and empty, unable to focus

- Eyes open, with fear evident on the face

- Hyperventilating or gasping

- Trying to swim in a particular direction but not making headway

- Trying to roll over on the back to float

- Uncontrollable movement of arms and legs, rarely out of the water.

Frank Pia, a lifeguard and researcher of rescue techniques and drowning, notes that drowning begins at the point a person is unable to keep their mouth above water; inhalation of water takes place at a later stage.[8] Most people demonstrating the instinctive drowning response do not show prior evidence of distress.[8]

Cause

Approximately 90% of drownings take place in freshwater (rivers, lakes and swimming pools) and 10% in seawater. Drownings in other fluids are rare, and often relates to industrial accidents. In New Zealand's early colonial history, so many settlers died while trying to cross rivers that drowning was known as "The New Zealand death".[9]

People have drowned in as little as 30 mm of water lying face down.[10] Children have drowned in baths, buckets and toilets; inebriates or those under the influence of drugs have died in puddles.

Drowning can also happen in ways that are less well known:

- Deep water blackout – caused by latent hypoxia upon ascent from depth, where the partial pressure of oxygen in the lungs under pressure at the bottom of a deep free-dive is adequate to support consciousness but drops below the blackout threshold as the water pressure decreases on the ascent. It usually strikes upon arriving near the surface as the pressure approaches normal atmospheric pressure.

- Shallow water blackout – caused by hyperventilation prior to swimming or diving. The primary urge to breathe (more precisely: to exhale) is triggered by rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the bloodstream.[11] The body detects CO2 levels very accurately and relies on this to control breathing.[11] Hyperventilation scrubs the blood of CO2 but leaves the diver susceptible to sudden loss of consciousness without warning from hypoxia. There is no bodily sensation that warns a diver of an impending blackout, and victims (often capable swimmers swimming under the surface in shallow water) become unconscious and drown quietly without alerting anyone to the fact that there is a problem; they are typically found on the bottom.

- Secondary drowning – Inhaled fluid can act as an irritant inside the lungs. Physiological responses to even small quantities include the extrusion of liquid into the lungs (pulmonary edema) over the following hours, but this reduces the ability to exchange air and can lead to a person "drowning in their own body fluid". Certain poisonous vapors or gases (as for example in chemical warfare), or vomit can have a similar effect. The reaction can take place up to 72 hours after a near drowning incident, and may lead to a serious condition or death.

Pathophysiology

Oxygen deprivation

A conscious person will hold his or her breath (see Apnea) and will try to access air, often resulting in panic, including rapid body movement. This uses up more oxygen in the blood stream and reduces the time to unconsciousness. The person can voluntarily hold his or her breath for some time, but the breathing reflex will increase until the person tries to breathe, even when submerged.[12]:702

The breathing reflex in the human body is weakly related to the amount of oxygen in the blood but strongly related to the amount of carbon dioxide (see Hypercapnia). During apnea, the oxygen in the body is used by the cells, and excreted as carbon dioxide. Thus, the level of oxygen in the blood decreases, and the level of carbon dioxide increases. Increasing carbon dioxide levels lead to a stronger and stronger breathing reflex, up to the breath-hold breakpoint, at which the person can no longer voluntarily hold his or her breath. This typically occurs at an arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 55 mm Hg, but may differ significantly from individual to individual and can be increased through training.

The breath-hold break point can be suppressed or delayed either intentionally or unintentionally. Hyperventilation before any dive, deep or shallow, flushes out carbon dioxide in the blood resulting in a dive commencing with an abnormally low carbon dioxide level; a potentially dangerous condition known as hypocapnia. The level of carbon dioxide in the blood after hyperventilation may then be insufficient to trigger the breathing reflex later in the dive and a blackout may occur without warning and before the diver feels any urgent need to breathe. This can occur at any depth and is common in distance breath-hold divers in swimming pools. Hyperventilation is often used by both deep and distance free-divers to flush out carbon dioxide from the lungs to suppress the breathing reflex for longer. It is important not to mistake this for an attempt to increase the body's oxygen store. The body at rest is fully oxygenated by normal breathing and cannot take on any more. Breath holding in water should always be supervised by a second person, as by hyperventilating, one increases the risk of shallow water blackout because insufficient carbon dioxide levels in the blood fail to trigger the breathing reflex.

A continued lack of oxygen in the brain, hypoxia, will quickly render a person unconscious usually around a blood partial pressure of oxygen of 25–30 mmHg. An unconscious person rescued with an airway still sealed from laryngospasm stands a good chance of a full recovery. Artificial respiration is also much more effective without water in the lungs. At this point the person stands a good chance of recovery if attended to within minutes.

A lack of oxygen or chemical changes in the lungs may cause the heart to stop beating. This cardiac arrest stops the flow of blood and thus stops the transport of oxygen to the brain. Cardiac arrest used to be the traditional point of death but at this point there is still a chance of recovery. The brain cannot survive long without oxygen and the continued lack of oxygen in the blood combined with the cardiac arrest will lead to the deterioration of brain cells causing first brain damage and eventually brain death from which recovery is generally considered impossible. The brain will die after approximately six minutes without oxygen but special conditions may prolong this.

Water aspiration

If water enters the airways of a conscious person, the person will try to cough up the water or swallow it, thus inhaling more water involuntarily. Upon water entering the airways, both conscious and unconscious persons experience laryngospasm, in which the larynx or the vocal cords in the throat constrict, sealing the airway. This prevents water from entering the lungs. Because of this laryngospasm, in the initial phase of drowning, water enters the stomach and very little water enters the lungs. Though laryngospasm prevents water from entering the lungs, it also interferes with breathing. In most persons, the laryngospasm relaxes some time after unconsciousness and water can enter the lungs causing a "wet drowning". However, about 7–10% of people maintain this seal until cardiac arrest.[12] This has been called "dry drowning", as no water enters the lungs. In forensic pathology, water in the lungs indicates that the person was still alive at the point of submersion. Absence of water in the lungs may be either a dry drowning or indicates a death before submersion.[13]

When water is taken into the lungs, it negatively affects blood chemistry. The mechanism differs for fresh and salt water.

- Fresh water taken into the lungs will be pulled into the pulmonary circulation by osmosis. The dilution of blood leads to hemolysis. The resulting elevation of plasma K+ (potassium) level and depression of Na+ (sodium) level alter the electrical activity of the heart, often causing ventricular fibrillation. In animal experiments this effect was shown to be capable of causing cardiac arrest in 2 to 3 minutes. Acute renal failure can also result from hemoglobin from the burst blood cells accumulating in the kidneys, and cardiac arrest can also result if cold fresh water taken into the bloodstream sufficiently cools the heart.

- Sea water is hypertonic to blood, due to higher salt content. It poses the opposite danger. Osmosis will instead pull water from the bloodstream into the lungs, thickening the blood. In animal experiments the thicker blood requires more work from the heart leading to cardiac arrest in 8 to 10 minutes.

Autopsies on drowned persons show no indications of these effects and there appears to be little difference between drownings in salt water and fresh water. After death, rigor mortis will set in and remains for about two days, depending on many factors, including water temperature.

Cold water immersion

Submerging the face in water cooler than about 21 °C (70 °F) triggers the mammalian diving reflex, found in mammals, and especially in marine mammals such as whales and seals. This reflex protects the body by putting it into energy saving mode to maximize the time it can stay under water. The strength of this reflex is greater in colder water and has three principal effects:

- Bradycardia, a slowing of the heart rate by up to 50% in humans.

- Peripheral vasoconstriction, the restriction of the blood flow to the extremities to increase the blood and oxygen supply to the vital organs, especially the brain.

- Blood Shift, the shifting of blood to the thoracic cavity, the region of the chest between the diaphragm and the neck, to avoid the collapse of the lungs under higher pressure during deeper dives.

The reflex action is automatic and allows both a conscious and an unconscious person to survive longer without oxygen under water than in a comparable situation on dry land. The exact mechanism for this effect has been debated and may be a result of brain cooling similar to the protective effects seen in patients treated with deep hypothermia.[14][15]

In very cold or freezing water reflex reactions can be lethal instead, killing up to 70% of people within 15–30 minutes, as they give rise first to cold shock, a combination of uncontrolled gasping and massively increased blood pressure with possible cardiac arrest, followed by the rapid loss of control of bodily functions needed for swimming and gripping.

[S]omething that almost no one in the maritime industry understands. That includes mariners [and] even many (most) rescue professionals: It is impossible to die from hypothermia in cold water unless you are wearing flotation, because without flotation – you won’t live long enough to become hypothermic.— Mario Vittone, lecturer and author in water rescue and survival[16]

Heat transfers very well through water, and body heat is therefore lost extremely quickly in water compared to air,[17] even in merely 'cool' swimming waters around 70F (~20C).[18] A water temperature of 10 °C (50 °F) can lead to death in as little as one hour, and water temperatures hovering at freezing can lead to death in as little as 15 minutes.[18] This is because cold water can have other lethal effects on the body, so hypothermia is not usually a reason for drowning or the clinical cause of death for those who drown in cold water.

The actual cause of death in cold or very cold water are usually lethal bodily reactions to increased heat loss and to freezing water, rather than any loss of core body temperature. Of those who die after plunging into freezing seas, around 20% die within 2 minutes from cold shock (uncontrolled rapid breathing and gasping causing water inhalation, massive increase in blood pressure and cardiac strain leading to cardiac arrest, and panic), another 50% die within 15 – 30 minutes from cold incapacitation (loss of use and control of limbs and hands for swimming or gripping, as the body 'protectively' shuts down the peripheral muscles of the limbs to protect its core),[16] and exhaustion and unconsciousness cause drowning, claiming the rest within a similar time.[18] A notable example of this occurred during the sinking of the Titanic, in which most people who entered the −2 °C (28 °F) water died within 15–30 minutes.[19]

Hypothermia (and also cardiac arrest) present a risk for survivors of immersion, as for survivors of exposure; in particular the risk increases if the survivor, feeling well again, tries to get up and move, not realizing their core body temperature is still very low and will take a long time to recover.

Diagnosis

The World Health Organization in 2005 defined drowning as "the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion/immersion in liquid".[1] This definition does not imply death, or even the necessity for medical treatment after removal of the cause, nor that any fluid enters the lungs. The WHO further recommended that outcomes should be classified as: death, morbidity, and no morbidity.[1] There was also consensus that the terms wet, dry, active, passive, silent, and secondary drowning should no longer be used.[1]

Experts differentiate between distress and drowning. They also divide drowning into passive and active:

- Distress – people in trouble, but who still have the ability to keep afloat, signal for help and take actions.

- Drowning – people suffocating and in imminent danger of death within seconds. Drowning falls into two categories:

- Passive drowning – people who suddenly sink or have sunk due to a change in their circumstances. Examples include people who drown in an accident, or due to sudden loss of consciousness or sudden medical condition.

- Active drowning – people such as non-swimmers and the exhausted or hypothermic at the surface, who are unable to hold their mouth above water and are suffocating due to lack of air. Instinctively, people in such cases perform well known behaviors in the last 20–60 seconds before being submerged, representing the body's last efforts to obtain air. Notably such people are unable to call for help, talk, reach for rescue equipment, or alert swimmers even feet away, and they may drown quickly and silently close to other swimmers or safety.[2]

Management

Rescue involves bringing the person's mouth and nose above the water surface. A drowning person may cling to the rescuer and try to pull himself out of the water, submerging the rescuer in the process. Thus it is advised that the rescuer approach with a buoyant object, or from behind, twisting the person's arm on the back to restrict movement. If the rescuer does get pushed under water, they should dive downwards to escape the person.

After a successful approach, negatively buoyant objects such as a weight belt are removed. The priority is then to transport the person to the water's edge in preparation for removal from the water. The person is turned on their back with a secure grip used to tow from behind. If the person is cooperative they may be towed in a similar fashion held at the armpits. If the person is unconscious they may be pulled in a similar fashion held at the chin and cheeks, ensuring that the mouth and nose are well above the water.

Special care has to be taken for people with suspected spinal injuries, and a back board (spinal board) may be needed for the rescue. In water, CPR is ineffective, and the goal should be to bring the person to a stable ground quickly and then to start CPR. Once on ground chest compressions are performed by the "C-A-B" scheme (Compressions-Airway opening-Breaths).[20] 100% oxygen is neither recommended nor discouraged.[21] Treatment for hypothermia may also be necessary.

The Heimlich maneuver is not recommended;[22] the technique may have relevance in situations where airways are obstructed by solids but not fluids. Performing the maneuver on drowning people not only delays ventilation but may induce vomiting, which if aspirated will place the patient in a far worse situation.

Because of the mammalian diving reflex (see above), people submerged in cold water and apparently drowned may revive after a relatively long period. In one case, a child submerged in cold (37 °F (3 °C)) water for 66 minutes was resuscitated without neurological damage.[23] Rescuers retrieving a child from water significantly below body temperature should attempt resuscitation even after protracted immersion.[23]

Surveillance

Many pools and designated bathing areas either have lifeguards, a pool safety camera system for local or remote monitoring, or computer-aided drowning detection. However, bystanders play an important role in drowning detection and either intervention or the notification of authorities by phone or alarm.

RID factors

The acronym RID was originated by Frank Pia to summarize important reasons why lifeguards may be unaware of a drowning. The term stands for "failure to recognize the struggle, the intrusion of non-lifeguard duties upon lifeguards' primary task-preventive lifeguarding, and the distraction from surveillance duties".[24] In his paper on the RID factors,[24] Pia makes a number of observations on the role, and the required behavior and training of lifeguards, as well as the importance of administrators directing lifeguards to this role and avoiding double tasking them (due to the very brief time of 20 – 60 seconds required for drowning to occur). He ended by summarizing the role of lifeguards as guardians of life, and that they should be directed exclusively to this duty and none other, while on surveillance, due to the high value placed on human life.

Epidemiology

In 2013 drowning was estimated to have resulted in 368,000 deaths down from 545,000 deaths in 1990.[5] It the third leading cause of death from unintentional trauma after traffic injuries and falls.[26]

In many countries, drowning is one of the leading causes of death for children under 12 years old. In the United States in 2006, 1100 people under 20 years of age died from drowning.[27] Typically the United Kingdom suffers 450 drownings per year or 1 per 150,000 of population whereas the United States suffers 6,500 drownings or around 1 per 50,000 of population. In Asia, according to a study by The Alliance for Safe Children, suffocation and drowning were the most easily preventable causes of death for children under five years of age;[28][29] a 2008 report by the organization found that in Bangladesh, for instance, 46 children drown each day.[30]

United States

In the United States, it is the second leading cause of death (after motor vehicle crashes) in children 12 and younger.[7]

People who drown are more likely to be male, young or adolescent.[7] Surveys indicate that 10% of children under 5 have experienced a situation with a high risk of drowning. Worldwide, about 175,000 children die through drowning every year.[31] The causes of drowning cases in the US from 1999 to 2006 are as follows:[32]

| 31.0% | Drowning and submersion while in natural water |

| 27.9% | Unspecified drowning and submersion |

| 14.5% | Drowning and submersion while in swimming pool |

| 9.4% | Drowning and submersion while in bathtub |

| 7.2% | Drowning and submersion following fall into natural water |

| 6.3% | Other specified drowning and submersion |

| 2.9% | Drowning and submersion following fall into swimming pool |

| 0.9% | Drowning and submersion following fall into bathtub |

Capital punishment

In Europe, drowning was used as capital punishment. In fact, during the Middle Ages, a sentence of death was read using the words "cum fossa et furca", or "with drowning-pit and gallows". Furthermore, drowning was used as a way to determine if a woman was a witch. The idea was that witches would float and innocent women would drown. For more details, see trial by drowning. It is understood that drowning was used as the least brutal form of execution, and was therefore reserved primarily for women, although favored men were executed in this way, as well.

Versions of this method of execution included throwing people in the water with weights attached and chaining people to rocks below the high tide line, and waiting for the water to cover and drown them.

Drowning survived as a method of execution in Europe until the 17th and 18th centuries.[33] England had abolished the practice by 1623, Scotland by 1685, Switzerland in 1652, Austria in 1776, Iceland in 1777, and Russia by the beginning of the 1800s. France revived the practice during the French Revolution (1789–1799) and was carried out by Jean-Baptiste Carrier at Nantes.[34]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 E.F. van Beeck; C.M. Branche; D. Szpilman; J.H. Modell; J.J.L.M. Bierens (2005), A new definition of drowning: towards documentation and prevention of a global public health problem, 83, Bulletin of the World Health Organization (published 11 November 2005), pp. 801–880, retrieved 19 July 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vittone, Mario; Pia, Francesco (Fall 2006). "'It Doesn't Look Like They're Drowning': How To Recognize the Instinctive Drowning Response" (PDF). On Scene: The Journal of U.S. Coast Guard Search and Rescue: p. 14. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ↑ O'Connell, Claire (3 August 2010). "What stops people shouting and waving when drowning?". Irish Times. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ↑ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (22 August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet (London, England). 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMID 26063472.

- 1 2 3 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442.

. PMID 25530442. - ↑ "Drowning". Fact sheet N°347. World Health Organization. November 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Drowning". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- 1 2 Pia, Frank (1999). "Chapter 14: Reflections on Lifeguard surveillance programs". In Fletemeyer, John R.; Freas, Samuel J. Drowning: New Perspectives on Intervention and Prevention. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-57444-223-6.

- ↑ Young, David (13 July 2012). "Rivers - The impact of European settlement". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Gulli, Benjamin, Joseph A. Ciatolla, and Leaugeay Barnes (2011). Emergency Care and Transportation of the Sick and Injured. Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett. p. 1157. ISBN 9780763778286.

- 1 2 Lindholm P, Lundgren CE; Lundgren (2006). "Alveolar gas composition before and after maximal breath-holds in competitive divers". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine : Journal of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, Inc. 33 (6): 463–7. PMID 17274316. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- 1 2 Gorman, Mark (2008). Jose Biller, ed. Interface of Neurology and Internal Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 702–706. ISBN 978-0-7817-7906-7. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ Dominick DiMaio; Vincent J.M. DiMaio, M.D. (28 June 2001). Forensic Pathology, Second Edition. Taylor & Francis. pp. 405–. ISBN 978-0-8493-0072-1. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ Lundgren, Claus EG; Ferrigno, Massimo (eds). (1985). "Physiology of Breath-hold Diving. 31st Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop". UHMS Publication Number 72(WS-BH)4-15-87. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

- ↑ Mackensen GB, McDonagh DL, Warner DS; McDonagh; Warner (March 2009). "Perioperative hypothermia: use and therapeutic implications". J. Neurotrauma. 26 (3): 342–58. doi:10.1089/neu.2008.0596. PMID 19231924.

- 1 2 Vittone, Mario (12 April 2013). http://www.gcaptain.com/cold_water/?11198 "The Truth About Cold Water". gCaptain and own website 2010-10-21.

- ↑ Sterba, JA (1990). "Field Management of Accidental Hypothermia during Diving". US Naval Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report. NEDU-1-90. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Hypothermia safety". United States Power Squadrons. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ↑ Sinking of the RMS Titanic#CITEREFButler1998

- ↑ http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@ecc/documents/downloadable/ucm_317350.pdf[]

- ↑ "2005 ILCOR resuscitation guidelines" (PDF). Circulation. 112 (22 supplement). 29 November 2005. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166480 (inactive 2016-10-16). Retrieved 17 February 2008.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of oxygen by the first aid provider.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Near drowning

- 1 2 McKenna, Kim D. (2011). Mosby's paramedic textbook. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 1262–1266. ISBN 978-0-323-07275-5. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- 1 2 Pia, Frank (June 1984). "The RID factor as a cause of drowning". Parks & Recreation. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Lozano, R; Naghavi, M; Foreman, K; Lim, S; Shibuya, K; Aboyans, V; Abraham, J; Adair, T; Aggarwal, R; Ahn, S. Y.; Alvarado, M; Anderson, H. R.; Anderson, L. M.; Andrews, K. G.; Atkinson, C; Baddour, L. M.; Barker-Collo, S; Bartels, D. H.; Bell, M. L.; Benjamin, E. J.; Bennett, D; Bhalla, K; Bikbov, B; Bin Abdulhak, A; Birbeck, G; Blyth, F; Bolliger, I; Boufous, S; Bucello, C; et al. (15 Dec 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ "Policy Statement—Prevention of Drowning—COMMITTEE ON INJURY, VIOLENCE, AND POISON PREVENTION, 10.1542/peds.2010-1264 – Pediatrics".

- ↑ "Drowning, Homicide and Suicide Leading Killers for Children in Asia". The Salem News. 11 March 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ↑ "UNICEF Says Injuries A Fatal Problem For Asian Children". All Headline News. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ↑ "Children Drowning, Drowning Children" (PDF). The Alliance for Safe Children. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ↑ "Traffic Accidents Top Cause Of Fatal Child Injuries". NPR: National Public Radio. 10 December 2008.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- ↑ Rictor Norton (17 November 2011). "Newspaper Reports: The Dutch Purge of Homosexuals, 1730". Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook.

- ↑ "Drowning and Life Saving". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

External links

- Canadian Red Cross: Drowning Research: Drownings in Canada, 10 Years of Research Module 2 – Ice & Cold Water Immersion* Canadian Lifesaving Society Canadian National Drowning Report (1991–2000).

- Drowning prevention information from Seattle Children's Hospital.

- Report into Lifeguard effectiveness, also covering drowning facts and risks – CDC, 2001

- World Health Organization fact-sheet on drowning with statistics (latest as of December 2010)