Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook

| The Right Honourable The Lord Beaverbrook PC, ONB | |

|---|---|

Lord Beaverbrook in 1943 | |

| Lord Privy Seal | |

|

In office 1943–1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Viscount Cranborne |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Greenwood |

| Minister of War Production | |

|

In office 4 February 1942 – 19 February 1942 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Lyttelton (as Minister of Production) |

| Minister of Supply | |

|

In office 29 June 1941 – 4 February 1942 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Sir Andrew Duncan |

| Succeeded by | Sir Andrew Duncan |

| Minister of Aircraft Production | |

|

In office 14 May 1940 – 1 May 1941 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | John Moore-Brabazon |

| Minister of Information | |

|

In office 10 February – 4 November 1918 | |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Downham |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

|

In office 10 February – 4 November 1918 | |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | Sir Frederick Cawley |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Downham |

| Member of Parliament for Ashton under Lyne | |

|

In office 3 December 1910 – 23 December 1916 | |

| Preceded by | Alfred Scott |

| Succeeded by | Albert Stanley |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Maxwell Aitken 25 May 1879 Maple, Ontario, Canada |

| Died |

9 June 1964 (aged 85) Surrey, England, United Kingdom |

| Political party |

Liberal Unionist Conservative |

| Occupation | Legislator, author, entrepreneur |

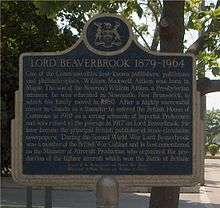

William Maxwell "Max" Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook, PC, ONB, (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964) was a Canadian business tycoon, politician, newspaper proprietor and writer who was an influential figure in British society of the first half of the 20th century.[1]

The young Max Aitken had a gift for making money and was a millionaire by 30. His business ambitions quickly exceeded what was then available to him in Canada and he moved to England. There he befriended Bonar Law and with his support won a seat in the House of Commons at the general election held in December 1910. A knighthood followed shortly after. During World War I, he ran the Canadian Records office in London and played a role in the removal of H. H. Asquith as prime minister in 1916. The resulting Tory-led coalition government, with David Lloyd George as prime minister and Bonar Law as Chancellor of the Exchequer, rewarded Aitken with a peerage and, briefly, a Cabinet post as Minister of Information.

Post-war, the now Lord Beaverbrook concentrated on his business interests. He built the Daily Express into the most successful mass circulation newspaper in the world and used it to pursue personal campaigns, most notably for tariff reform and for the British Empire to become a free trade bloc. Beaverbrook supported appeasement throughout the 1930s but was persuaded by another long standing political friend, Winston Churchill, to serve as Minister of Aircraft Production in 1940. After numerous clashes with other Cabinet members he resigned in 1941 but later in the war was appointed Lord Privy Seal. Beaverbrook spent his later life running his newspapers, which by then included the London Evening Standard and the Sunday Express.[2] He served as Chancellor of the University of New Brunswick and developed a reputation as a historian with his books on political and military history.[3][4]

Early life

Aitken was born in Maple, Ontario, Canada, (near Keele Street and Major Mackenzie Drive) in 1879, one of the ten children of William Cuthbert Aitken, a Scottish-born Presbyterian minister and Jane Noble, the daughter of a prosperous local farmer and storekeeper. The following year, the family moved to Newcastle, New Brunswick which Aitken considered to be his hometown. It was here, at the age of 13, that he set up a school newspaper, The Leader. Whilst at school, he delivered newspapers, sold newspaper subscriptions and was the local correspondent for the St. John Daily Star.[5] Aitken took the entrance examinations for Dalhousie University, but because he had refused to sit the Greek and Latin papers he was refused entry. He registered at the King's College Law School, but left after a short while. This was to be his only formal higher education. Aitken worked in a shop then borrowed some money to move to Chatham, New Brunswick where he worked as a local correspondent for the Montreal Star, sold life insurance and also collected debts. Aitken attempted to train as a lawyer and worked for a short time in the law office of Richard Bedford Bennett, a future Prime Minister of Canada. Aitken managed Bennett's successful campaign for a place on Chatham Town Council. When Bennett left the law firm, Aitken moved to Saint John, New Brunswick where he again sold life insurance before moving to Calgary where he helped to run Bennett's campaign for a seat in the Legislative Assembly of the North-West Territories in the 1898 general election. After an unsuccessful attempt to establish a meat business, Aitken returned to Saint John and to selling insurance.[6]

Early business career

In 1900, Aitken made his way to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where John F. Stairs, a member of the city's dominant business family, gave him employment and trained him in the business of finance. In 1904, when Stairs launched the Royal Securities Corporation, Aitken became a minority shareholder and the firm's general manager. Under the tutelage of Stairs, who would be his mentor and friend, Aitken engineered a number of successful business deals and was planning a series of bank mergers. Stairs' unexpected early death in late September 1904 led to Aitken acquiring control of the company and moving to Montreal. There he bought and sold companies, invested in stocks and shares and also developed business interests in both Cuba and Puerto Rico. He started a weekly magazine, the Canadian Century in 1910, invested in the Montreal Herald and almost acquired the Montreal Gazette.[6] In 1907 he founded the Montreal Engineering Company.[7] In 1909, also under the umbrella of his Royal Securities Company, Aitken founded the Calgary Power Company Limited, now the TransAlta Corporation, and oversaw the building of the Horseshoe Falls hydro station.[8]

In 1910-11 Aitken acquired many of the small regional cement plants across Canada, including Sandford Fleming's Western Canada Cement Co. plant at Exshaw, Alberta, and amalgamated them into Canada Cement, eventually controlling four-fifths of the cement production in Canada. Canada was booming economically at the time and Aitken had a monopoly on the material. There were irregularities in the stock transfers leading to the conglomeration of the cement plants, resulting in much criticism of Aitken, as well as accusations of price-gouging and poor management of the cement plants under his company's control.[9] Aitken sold his shares, making a large amount of money, then left for Britain. Aitken had made his first visit to Britain in September 1908 and when he returned there in the Spring of 1910, in an attempt to raise money to buy a steel company, he decided to make the move permanent.[6]

Move to Britain

In 1910 Aitken moved to Britain and he became friends with Andrew Bonar Law, another native of New Brunswick and the only Canadian to become Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The two men had a lot in common—they were both sons of the manse from Scottish-Canadian families and both were successful businessmen. Aitken persuaded Bonar Law to support him in standing for the Unionist Party in the December 1910 general election at Ashton-under-Lyne. Although Aitken was a poor public speaker he was an excellent organiser and, with plenty of money for publicity, he won the seat by 196 votes.[6][10] Aitken rarely spoke in the House of Commons, but did promise substantial financial support to the Unionist Party, and in 1911 he was knighted by King George V. Aitken's political influence grew when Bonar Law replaced A.J. Balfour as leader of the Unionist party late in 1911. Aitken bought Cherkley Court near Leatherhead and entertained lavishly there. In 1913 the house was offered as a venue for negotiations, between Bonar Law and the Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, over Ulster and Irish home rule.[6]

Aitken continued to grow his business interests while in Parliament and also began to build a British newspaper empire. After the death of Charles Rolls in 1910, Aitken bought his shares in Rolls-Royce Limited, and over the next two years gradually increased his holding in the company. However, Claude Johnson, Rolls-Royce's Commercial managing director, resisted Aitken's attempt to gain control of the company, and in October 1913 he sold his holding to James Buchanan Duke, of the American Tobacco Company.[11] In January 1911, Aitken, secretly, invested £25,000 in the failing Daily Express. An attempt to buy the London Evening Standard failed but he did gain control of another London evening paper, The Globe. In November 1916 a share deal worth £17,500, with Lawson Johnson, landed Aitken a controlling interest in the Daily Express, but again he kept the deal secret.[6]

World War One

.jpg)

During World War I, the Canadian government put Aitken in charge of creating the Canadian War Records Office in London, and he made certain that news of Canada's contribution to the war was printed in Canadian and British newspapers. He was innovative in the employment of artists, photographers, and film makers to record life on the Western Front. Aitken also established the Canadian War Memorials Fund that evolved into a collection of war art by the premier artists and sculptors in Britain and Canada.[12] His visits to the Western Front, with the honorary rank of colonel in the Canadian Army, resulted in his 1916 book Canada in Flanders, a three-volume collection that chronicled the achievements of Canadian soldiers on the battlefields. After the war, Aitken wrote several books including Politicians and the Press in 1925 and Politicians and the War in 1928.

Aitken became increasingly hostile towards the Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith whom he considered to be mismanaging the war effort. Aitken's opinion of Asquith didn't improve when he failed to get a post in the Cabinet reshuffle of May 1915. An attempt by Bonar Law to secure the KCMG for Aitken was also blocked by Asquith. Aitken was happy to play a small part, which he greatly exaggerated, as a go-between when Asquith was forced from office and replaced by David Lloyd George in December 1916.[6] Lloyd George offered to appoint Aitken as President of the Board of Trade. At that time, an MP taking a cabinet post for the first time had to resign and stand for re-election in a by-election. Aitken made arrangements for this, but then Lloyd George decided to appoint Albert Stanley instead. Aitken was a friend of Stanley and agreed to continue with the resignation, so that Stanley could take Aitken's seat in Parliament and be eligible for ministerial office. In return, Aitken received a peerage in 1917 as the 1st Baron Beaverbrook,[13] the name "Beaverbrook" being adopted from a small community near his boyhood home. He had initially considered "Lord Miramichi", but rejected it on the advice of Louise Manny as too difficult to pronounce.[14][15][16] The name "Beaverbrook" also had the advantage of conveying a distinctive Canadian ring to the title.

Later in 1917, Beaverbrook's controlling stake in the Daily Express became public knowledge and he was criticised by parts of the Conservative Party for financing a publication they regarded as irresponsible and often unhelpful to the party.[6]

In February 1918, Beaverbrook became the first Minister of Information in the newly formed Ministry of Information and was also made Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster with a seat in Cabinet. Beaverbrook became responsible for propaganda in Allied and neutral countries and Lord Northcliffe became Director of Propaganda with control of propaganda in enemy countries. Beaverbrook established the British War Memorials Committee within the Ministry, on lines similar to the earlier Canadian war art scheme, but when he established a private charity that would receive income from BWMC exhibitions, it was regarded as a conflict of interest and he dropped the scheme.[12] Beaverbrook had a number of clashes with the Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour over the use of intelligence material. He felt that intelligence should become part of his department, but Balfour disagreed. Eventually the intelligence committee was assigned to Beaverbrook but they then resigned en masse to be re-employed by the Foreign Office. In August 1918, Lloyd George became furious with Beaverbrook over a leader in the Daily Express threatening to withdrew support from the government over tariff reform. Beaverbrook increasingly came under attack from MPs who distrusted a press baron being employed by the state. Beaverbrook survived but became increasingly frustrated with his limited role and influence, and in October 1918, he resigned, claiming ill health.[6]

A J P Taylor later wrote that Beaverbrook was a pathbreaker who "invented all the methods of publicity" used by Britain to promote the war, including the nation's first war artists, the first war photographers, and the first makers of war films. He was especially effective in promoting the sales of war bonds to the general public. Nevertheless, he was widely disliked and distrusted by the political elite, who were suspicious of all they sneeringly called "press lords."[17]

First Baron of Fleet Street

After the war, Beaverbrook concentrated on running the Daily Express. He turned the dull newspaper into a glittering and witty journal with an optimistic attitude, filled with an array of dramatic photo layouts. He hired first-rate writers such as Francis Williams and the cartoonist David Low. He embranced new technology and bought new presses to print the paper in Manchester. In 1919 the circulation of the Daily Express was under 40,000 a day; by 1937 it was 2,329,000 a day, making it the most successful of all British newspapers and generating huge profits for Beaverbrook whose wealth was already such that he never took a salary. After the Second World War, the Daily Express became the largest-selling newspaper in the world by far, with a circulation of 3,706,000. Beaverbrook launched the Sunday Express in December 1918, but it only established a significant readership after John Junor became its editor in 1954. In 1923, in a joint deal with Lord Rothermere, Beaverbrook bought the London Evening Standard. Beaverbrook acquired a controlling stake in the Glasgow Evening Citizen and, in 1928, he launched the Scottish Daily Express.[6]

Beaverbrook would become regarded by some historians as the first baron of Fleet Street and as one of the most powerful men in Britain whose newspapers could make or break almost anyone. Beaverbrook enjoyed using his papers to attack his opponents and to promote his friends. From 1919 to 1922 he attacked David Lloyd George and his government on several issues. He began supporting independent Conservative candidates and campaigned for fifteen years to remove Stanley Baldwin from the leadership of the Conservative Party. He very shrewdly sold the majority of his share holdings before the 1929 crash and in the resulting depression launched a new political party to promote free trade within the British Empire. Empire Free Trade Crusade candidates had some success. An Independent Conservative who supported Empire Free Trade won the Twickenham by-election in 1929. The Empire Free Trade candidate won the South Paddington by-election in October 1930. In February 1931, Empire Free Trade lost the Islington East by-election and allowed Labour to hold a seat they had been expected to lose. Duff Cooper's victory for the Conservatives in St. George's Westminster by-election in March 1931 marked the end of the movement as an electoral force.[6]

On 17 March 1931, during the St. George's Westminster by-election, Stanley Baldwin described the media barons who owned British newspapers as having "Power without responsibility – the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages." In the 1930s, while personally attempting to dissuade King Edward VIII from continuing his potentially ruinous affair with American divorcee, Wallis Simpson, Beaverbrook's newspapers published every titbit of the affair, especially allegations about pro-Nazi sympathies. Beaverbrook supported the Munich Agreement and hoped the newly named Duke of Windsor would seek a peace deal with Germany.

Testifying before a Parliamentary inquiry in 1947, former Express employee and future MP Michael Foot alleged that Beaverbrook kept a blacklist of notable public figures who were to be denied any publicity in his papers because of personal disputes. Foot said they included Sir Thomas Beecham, Paul Robeson, Haile Selassie, and Noël Coward. Beaverbrook himself gave evidence before the inquiry and vehemently denied the allegations; Express Newspapers general manager E.J. Robertson denied that Robeson had been blacklisted, but did admit that Coward had been "boycotted" because he had enraged Beaverbrook with his film In Which We Serve—in the opening sequence Coward includes an ironic shot showing a copy of the Daily Express floating in the dockside garbage bearing the headline "No War This Year".[18][19][20]

The Second World War

_during_the_Second_World_War_HU88386.jpg)

In the late 1930s Beaverbrook had used his newspapers to promote the appeasement policies of the Chamberlain government. The slogan 'There will be no war' was used by the Daily Express.[21] During the Second World War, in May 1940, his friend Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, appointed Beaverbrook as Minister of Aircraft Production. With Churchill's blessing Beaverbrook overhauled all aspects of war-time aircraft production;- he increased production targets by 15% across the board, took control of aircraft repairs and RAF storage units, replaced the management of plants that were underperforming, and released German Jewish engineers from internment to work in the factories. He seized materials and equipment destined for other departments and was perpetually at odds with the Air Ministry.[22] Under Beaverbrook, fighter and bomber production increased so much so that Churchill declared: "His personal force and genius made this Aitken's finest hour." Beaverbrook's impact on wartime production has been much debated but his innovative style certainly energised production at a time when it was desperately needed. However it has been argued that aircraft production was already rising when Beaverbrook took charge and that he was fortunate to inherit a system which was just beginning to bear fruit.[23] His appeal for housewives to give up their aluminium pots and pans “to make Spitfires” was afterwards revealed by his son Sir Max Aitken to have been a waste of good pans. They were of no use at all for aircraft production. The appeal had been nothing more than a propaganda exercise, he said in the TV documentary series The World at War. Still, a Time Magazine cover story declared, "Even if Britain goes down this fall [1940], it will not be Lord Beaverbrook's fault. If she holds out, it will be his triumph. This war is a war of machines. It will be won on the assembly line."[24]

Beaverbrook resigned on 30 April 1941 and, after a month as Minister of State, Churchill appointed him to the post of Minister of Supply. Here Beaverbrook clashed with Ernest Bevin who, as Minister of Labour and National Service, refused to let Beaverbrook take over any of his responsibilities. In February 1942, Beaverbrook became Minister of War Production and again clashed with Bevin, this time over shipbuilding. In the face of Bevin's refusal to work with him, Beaverbrook resigned after only twelve days in the post. In September 1943 he was appointed Lord Privy Seal, outside of the Cabinet, and held that post until the end of the war.[6]

In 1941, Beaverbrook headed the British delegation to Moscow with his American counterpart Averell Harriman. This made Beaverbrook the first senior British politician to meet Soviet leader Joseph Stalin since Hitler's invasion of the Soviet Union. Much impressed by Stalin and the sacrifice of the Soviet people, he returned to London determined to persuade Churchill to launch a second front in Europe to help draw German resources away from the Eastern Front to aid the Soviets.[25] Despite their disagreement over the second front, Beaverbrook remained a close confidant of Churchill throughout the war, and could regularly be found with Churchill until the early hours of the morning. Clement Attlee commented that "Churchill often listened to Beaverbrook's advice but was too sensible to take it."

In addition to his ministerial roles, Beaverbrook headed the Anglo-American Combined Raw Materials Board from 1942 to 1945 and accompanied Churchill to several wartime meetings with President Roosevelt. He was able to relate to Roosevelt in a different way to Churchill and became close to Roosevelt during these visits. This friendship sometimes irritated Churchill who felt that Beaverbrook was distracting Roosevelt from concentrating on the war effort. For his part Roosevelt seems to have enjoyed the distraction.

Later life

Beaverbrook devoted himself to Churchill's 1945 General Election campaign, but a Daily Express headline warning that a Labour victory would amount to the 'Gestapo in Britain' was a huge mistake and completely misjudged the public mood.[5] Beaverbrook renounced his British citizenship and left the Conservative Party in 1951 but remained an Empire loyalist throughout his life. He opposed both Britain's acceptance of post-war loans from America and Britain's application to join the European Economic Community in 1961.[6] In 1953 he became chancellor of the University of New Brunswick and became the university's greatest benefactor, fulfilling the same role for the city of Fredericton and the province as a whole. He would provide additions to the university, scholarship funds, the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, the Beaverbrook Skating Rink, the Lord Beaverbrook Hotel, with profits donated to charity, the Playhouse, Louise Manny's early folklore work, and numerous other projects. He bought the archive papers of both Bonar Law and David Lloyd George and placed them in the Beaverbrook Library within the Daily Express Building.[6]

Historian

After the First World War, Beaverbrook had written Politicians and the Press in 1925 and Politicians and the War in 1928 and had the two books were reprinted in one volume in 1960.[26] Upon original publication, the books were largely ignored by professional historians and the only favourable reviews were in Beaverbrook's newspapers.[27] However, when the combined edition came out, the reviews were positive: "This is Suetonius or Macaulay presented with all the visual techniques of Alfred Hitchcock", and another review said that it was as "terse as Sallust, pithy as Clarendon". A. J. P. Taylor said it was "Tacitus and Aubrey rolled into one".[28]

Later on, Taylor said "The enduring merits of the book are really beyond cavil. It provides essential testimony for events during a great political crisis...It contains character sketches worthy of Aubrey. On a wider canvas, it displays the behaviour of political leaders in wartime. The narrative is carried along by rare zest and wit, yet with the detached impartialty of the true scholar".[29] Sir John Elliot in 1981 said the work "will remain, despite all carping, the authoritative narrative; nor does the story want in the telling thereof".[30]

Men and Power 1917–1918 was published in 1956. It is not a coherent narrative but divided by separate episodes centred on one man, such as Carson, Robertson, Rothermere and others. The reviews were favourable, with Taylor's review in The Observer greatly pleasing Beaverbrook.[31] The book sold over 23,000 copies.[32]

When The Decline and Fall of Lloyd George was published in 1963, favourable reviewers included Clement Attlee, Roy Jenkins, Robert Blake, Lord Longford, Sir Charles Snow, Lady Violet Bonham Carter, Richard Crossman and Denis Brogan.[33] Kenneth Young said the book was "the finest of all his writing".[33]

Beaverbrook was both admired and despised in Britain, sometimes at the same time: in his 1956 autobiography, David Low quotes H.G. Wells as saying of Beaverbrook: "If ever Max ever gets to Heaven, he won't last long. He will be chucked out for trying to pull off a merger between Heaven and Hell after having secured a controlling interest in key subsidiary companies in both places, of course."

Death

Lord Beaverbrook died in Surrey in 1964, aged 85. He had recently attended a birthday banquet organised by fellow Canadian press baron, Lord Thomson of Fleet, where he was determined to be seen on his usual good form, despite being riddled with painful cancer. The Beaverbrook Foundation continues his philanthropic interests. In 1957, a bronze statue of Lord Beaverbrook was erected at the centre of Officers' Square in Fredericton, New Brunswick, paid for by money raised by children throughout the province. A bust of him by Oscar Nemon stands in the park in the town square of Newcastle, New Brunswick, not far from where he sold newspapers as a young boy. His ashes are in the plinth of the bust.

Legacy

Beaverbrook and his wife Lady Beaverbrook have left a considerable legacy to his adopted province of New Brunswick and the United Kingdom, among others. In 2016, he was named a National Historic Person on the advice of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.[34] His legacy includes the following buildings (or at least his name survives in the names of these buildings):

- University of New Brunswick

- Aitken House[35]

- Aitken University Centre

- Lady Beaverbrook Gymnasium

- Lady Beaverbrook Residence[36]

- Beaverbrook House (UNBSJ E-Commerce Centre)

- City of Fredericton, New Brunswick

- Lady Beaverbrook Arena (formerly operated by the University of New Brunswick)

- The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, including world-renowned art collection (New Brunswick's provincial gallery)

- The Fredericton Playhouse

- Lord Beaverbrook Hotel

- Lord Beaverbrook statue in Officer's Square

- City of Miramichi, New Brunswick

- Lord Beaverbrook Arena (LBA)

- Beaverbrook Kin Centre (formerly the Beaverbrook Theatre and Town Hall)

- Beaverbrook House (his boyhood home and formerly the Old Manse Library)

- Lord Beaverbrook bust in Queen Elizabeth Park

- Aitken Avenue

- City of Campbellton, New Brunswick

- Lord Beaverbrook School

- City of Saint John, New Brunswick

- Lord Beaverbrook Rink

- City of Ottawa, Ontario

- City of Calgary, Alberta

- McGill University

- The Beaverbrook Chair in Ethics, Media and Communications[37]

Family

On 29 January 1906, in Halifax, Aitken married Gladys Henderson Drury, daughter of Major-General Charles William Drury CBE (a first cousin of Admiral Sir Charles Carter Drury) and Mary Louise Drury (née Henderson). They had three children before her death in 1927. His son Max Aitken Jr. became a fighter pilot with 601 Squadron, rising to Wing Commander with 16 victories in World War Two. Beaverbrook remained a widower for many years until 1963 when he married Marcia Anastasia Christoforides (1910–1994), the widow of his friend Sir James Dunn. Beaverbrook was rarely a faithful husband and even in old age was often accused of treating women with disrespect.[6]

- Hon. Janet Gladys Aitken (9 July 1908 – 18 November 1988); she married Ian Douglas Campbell, 11th Duke of Argyll, on 12 December 1927 and they were divorced in 1934. They have one daughter and two granddaughters. She remarried Hon. William Montagu on 5 March 1935. They have one son and three grandchildren. She remarried again, Major Thomas Kidd, on 11 July 1942. They have two children, three grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

- Lady Jeanne Campbell (10 December 1928 – 9 June 2007); she married Norman Mailer in 1962 and they were divorced in 1963. They have a daughter. She remarried John Sergeant Cram in March 1964. They have one daughter.

- Kate Mailer (18 August 1962)

- Cusi Cram (1967)

- William Montagu (9 February 1936 – 6 November 2002); he married Edna Ahlers in 1969. They have three children:

- Michael Drogo Montagu (10968)

- Nicola Lilian Montagu (1971)

- Monette Edna Montagu (1973)

- Jane Kidd (1943); she married Graham Morison Vere Nicoll in 1972.

- John Kidd (12 December 1944); he married Wendy Madeleine Hodge on 2 April 1973. They have three children and three grandchildren:

- Jack Kidd (1973)

- Jemma Kidd (20 September 1974); she married Arthur Wellesley, Marquess of Douro, on 4 June 2005. They have three children.

- Jodie Kidd (25 September 1978); she married Aidan Butler on 10 September 2005 and they were divorced in 2007. She remarried David Blakeley on 16 August 2014 and they were divorced on 1 May 2015.

- Lady Jeanne Campbell (10 December 1928 – 9 June 2007); she married Norman Mailer in 1962 and they were divorced in 1963. They have a daughter. She remarried John Sergeant Cram in March 1964. They have one daughter.

- |Sir John William Maxwell Aitken (15 February 1910 – 30 April 1985); he married Cynthia Monteith on 26 August 1939 and they were divorced in 1944. He remarried Ursula Kenyon-Slaney on 15 August 1946 and they were divorced in 1950. They have two daughters, five grandchildren, and two great-granddaughters. He remarried again Violet de Trafford on 1 January 1951. They have two children, seven grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren.

- Hon. Kirsty Jane Aitken (22 June 1947); she married Jonathan Morley on 6 September 1966 and they were divorced in 1973. They have two sons and two granddaughters. She remarried Christopher Smallwood in 1975. They have one daughter.

- Dominic Max Michael Morley (1967)

- Sebastian Finch Morley (1969); he married Victoria Whitbread in 1993. They have two daughters.

- Violet Mary Davina Morley (3 February 2004)

- Myrtle Rose Beatrice Morley (13 December 2005)

- Eleanor Bluebell Smallwood (1982)

- Hon. Lynda Mary Kathleen Aitken (30 October 1948); she married Nicholas Saxton on 25 April 1969 and they were divorced in 1974. She remarried Jonathan Dickson in 1977. They have two sons.

- Joshua James Dickson (20 February 1977)

- Leo Casper Dickson (1981)

- Maxwell Aitken, 3rd Baron Beaverbrook (29 December 1951); he married Susan O'Ferrall on 19 July 1974. They have four children and four grandchildren.

- Hon. Laura Aitken (18 November 1953); she married David Mallet in 1984. They have one son. She remarried Martin K. Levi in 1992. They have two children.

- David Sonny Victor Maxwell Mallet (1984)

- Lucci Violet Levi (1993)

- Louis Max Adam Levi (1 December 1994)

- Hon. Kirsty Jane Aitken (22 June 1947); she married Jonathan Morley on 6 September 1966 and they were divorced in 1973. They have two sons and two granddaughters. She remarried Christopher Smallwood in 1975. They have one daughter.

- Captain Hon. Peter Rudyard Aitken (22 March 1912- 3 August 1947); he married Janet Macneil on 25 January 1934 and they were divorced in 1939. They have one daughter and three grandsons. He remarried Marie Patricia McGuire on 28 October 1942. They have two sons and four grandsons.

- Caroline Ann Christine Aitken (4 April 1935); she married Conyers Baker on 7 September 1957. They have three sons:

- William Hugh Massey Baker (26 June 1958)

- Philip Massey Baker (13 March 1960)

- Jonathan Piers Massey Baker (14 July 1967)

- Timothy Maxwell Aitken (28 October 1944); he married Annete Hansen on 10 May 1966. He remarried Julie Filstead in 1972. They have two sons.

- Theodore Maxwell Aitken (1976)

- Charles Howard Filstead Aitken (1979)

- Peter Michael Aitken (20 February 1946); he married, secondly, Hon. Joan Rees-Williams in 1981 and they were divorced in 1985. He remarried Iryna Iwachiw on 12 September 1992.

- James Aitken

- Jason Aiken

- Caroline Ann Christine Aitken (4 April 1935); she married Conyers Baker on 7 September 1957. They have three sons:

Bibliography

- Canada in Flanders London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1916.

- Success. Small, Maynard and Company, 1922, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7661-5409-4.

- Politicians and the Press. London: Hutchinson, 1925.

- Politicians and the War, Vol. 1. London: Oldbourne, 1928.

- Politicians and the War, Vol. 2. London: Oldbourne, 1932.

- The Resources of The British Empire.London: Lane Publications, 1934.

- Why Didn't you Help the Finns? Are you in the Hands of the Jews? And 10 Questions, Answers. London: London Express, 1939.

- Spirit of the Soviet Union. London: The Pilot Press, 1942.

- Don't Trust to Luck. London: London Express Newspaper, 1954.

- The Three Keys to Success. London: Hawthorn Books, 1956.

- Men and Power, 1917–1918. North Haven, Connecticut: The Shoe String Press, 1956.

- Friends: Sixty years of Intimate personal relations with Richard Bedford Bennett. London: Heinemann, 1959.

- Courage, The Story of Sir James Dunn. Fredericton: Brunswick Press, 1961.

- My Early Life. Fredericton: Atlantic Advocate Book, 1962.

- The Divine Propagandist. London: Heinnemann, 1962.

- The Decline and Fall of Lloyd George: and great was the fall thereof. London: Collins, 1963, 1981 ISBN 978-0-313-23007-3.

- The Abdication of Edward VIII. NY: Atheneum, 1966.

In popular culture

For a period of time Beaverbrook employed novelist Evelyn Waugh in London and abroad. Waugh later lampooned his employer by portraying him as Lord Copper in Scoop and as Lord Monomark in both Put Out More Flags and Vile Bodies.

The Kinks recorded "Mr. Churchill Says" for their 1969 album Arthur, which contains the lines: "Mr. Beaverbrook says: 'We've gotta save our tin/And all the garden gates and empty cans are gonna make us win...'."

Beaverbrook was one of eight notable Britons cited in Bjørge Lillelien's famous "Your boys took a hell of a beating" commentary at the end of an English football team defeat to Norway in 1981, mentioned alongside British Prime Ministers Churchill, Thatcher and Attlee.[38][39]

In the alternate history novel, Dominion by C. J. Sansom, Beaverbrook served as Prime Minister from 1945 to 1953, heading a coalition government that consisted of the pro-Treaty factions of the Conservative Party and Labour Party, as well as the British Union of Fascists.[40]

In Jacqueline Winspear's mystery series featuring Maisie Dobbs, Beaverbrook appears as the ruthless John Otterburn, press baron and Churchill's minister of aviation, in the novels Elegy for Eddie and Leaving Everything Most Loved.

See also

References

- ↑ "Aitken, William Maxwell, 1st Baron Beaverbrook." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved: 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Peter Jackson & Tom de Castella (14 July 2011). "Clash of the press titans". BBC News. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ John Ramsden (Editor) (2005). Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century British Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861036-X.

- ↑ Peter Mavrikis (Editor) (2005). History of World War II. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. ISBN 978-0-7614-7231-5.

- 1 2 Frank N. Magill (Editor) (1999). Dictionary of World Biography Vol VII The 20th Century A-Gl. Salem Press. ISBN 0-89356-321-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 HCG Matthew & Brian Harrison (Editors) (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Vol 1 (Arron-Amory). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861351-2.

- ↑ Gregory P. Marchildon (1996). "5. The Montreal Engineering Company". Profits and politics: Beaverbrook and the gilded age of Canadian finance. University of Toronto Press. pp. 97–121.

- ↑ "100 Years, 100 People:1909–1919". TransAlta. 2 December 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ The New York Times, 13 May 1911, "Canadian Cement Scandal,"; Edmonton Bulletin, Nov. 30, 1911

- ↑ Firstworldwar.com. "Who's Who – Lord Beaverbrook". Firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Pugh 2001

- 1 2 Merion Harries & Susie Harries (1983). The War Artists, British Official War Art of the Twentieth Century. Michael Joseph, The Imperial War Museum & the Tate Gallery. ISBN 071812314X.

- ↑ Blake 1955, pp. 346–347.

- ↑ "St John NB & The Magnificent Irvings + Art heist at Beaverbrook Gallery." wordpress.com, 18 August. 2008. Retrieved: 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Rayburn, A. Naming Canada: Stories about Canadian Place Names. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

- ↑ Rayburn 1975

- ↑ Taylor 1972, pp. 137 (quote), 129, 135, 136.

- ↑ Movie 'In Which We Serve' 0:05:57

- ↑ Sweet 2005, p. 173.

- ↑ Anne Chisholm and Michael Davie, Lord Beaverbrook: a life (1993) p 458

- ↑ Geoffrey Cox 'Countdown to War' page 104

- ↑ Geoffrey Best (2005). Churchill and War. Humbledon and London. ISBN 1852854642.

- ↑ Deighton 1980, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ "Great Britain: Shirts On." Time, 16 September 1940.

- ↑ "Lord Beaverbrook." Spartacus. Retrieved: 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Taylor, p. 102.

- ↑ Taylor, p. 251.

- ↑ Taylor, p. 645.

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ John Elliot, ‘Aitken, William Maxwell, first Baron Beaverbrook (1879–1964)’, Dictionary of National Biography (1981).

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 629–630.

- ↑ Taylor, p. 629.

- 1 2 Taylor, p. 655.

- ↑ Sir William Maxwell Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook), Parks Canada backgrounder, Feb. 15, 2016

- ↑ "Aitken House." unbf.ca. Retrieved: 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "Lady Beaverbrook Residence." unb.ca. Retrieved: 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "The Beaverbrook Chair in Ethics, Media and Communications." mcgill.ca. Retrieved: 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Video on YouTube

- ↑ "News." BBC via Youtube. Retrieved: 13 March 2012.

- ↑ Sansom, C.J. "My nightmare of a Nazi Britain." The Guardian, 19 October 2012.

Further reading

- Chisholm, Anne and Michael Davie. Lord Beaverbrook: A Life. New York: Knopf, 1993. ISBN 978-0-394-56879-9.

- Deighton, Len. Battle of Britain. London: Johnathon Cape, 1980. ISBN 0-224-01826-4.

- Pugh, Peter. The Magic of a Name: The Rolls-Royce Story, The First 40 Years. London: Icon Books, 2001. ISBN 1-84046-151-9.

- Rayburn, A. Geographical Names of New Brunswick. Ottawa: Canadian Permanent Committee on Geographical Names, 1975.

- Richards, David Adams. Lord Beaverbrook (Extraordinary Canadians). Toronto, Ontario:Penguin Canada, 2008. ISBN 978-0-670-06614-8.

- Sweet, Matthew. Shepperton Babylon: The Lost Worlds of British Cinema. London: Faber & Faber, 2005. ISBN 978-0-571-21297-2.

- Taylor, A. J. P. Beaverbrook. London: Hamilton, 1972. ISBN 0-241-02170-7.

External links

- Lord Beaverbrook, a Week at the Office

- National Film Board of Canada biography

- Works by Max Aitken at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Max Aitken at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Lord Beaverbrook at Internet Archive

- Ontario Plaques – Lord Beaverbrook

- "Archival material relating to Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook". UK National Archives.

- The Beaverbrook Papers at the UK Parliamentary Archives

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Max Aitken

-

"Beaverbrook, William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

"Beaverbrook, William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alfred Scott |

Member of Parliament for Ashton-under-Lyne 1910–1916 |

Succeeded by Albert Stanley |

| Political offices | ||

| New office | Minister of Information 1918 |

Succeeded by The Lord Downham |

| Preceded by Sir Frederick Cawley |

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster 1918 | |

| New office | Minister of Aircraft Production 1940–1941 |

Succeeded by John Moore-Brabazon |

| Preceded by Sir Andrew Duncan |

Minister of Supply 1941–1942 |

Succeeded by Sir Andrew Duncan |

| New office | Minister of War Production 1942 |

Succeeded by Oliver Lyttelton as Minister of Production |

| Preceded by Viscount Cranborne |

Lord Privy Seal 1943–1945 |

Succeeded by Arthur Greenwood |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Baron Beaverbrook 1917–1964 |

Succeeded by John William Maxwell Aitken |

| Baronetage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Baronet (of Cherkley) 1916–1964 |

Succeeded by John William Maxwell Aitken |