Five Holy Wounds

In Christian tradition, the Five Holy Wounds or Five Sacred Wounds are the five piercing wounds Jesus suffered during the Crucifixion. The wounds have been the focus of particular devotions, especially in the late Middle Ages, and have often been reflected in church music and art.

History

The revival of religious life and the zealous activity of Bernard of Clairvaux and Francis of Assisi in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, together with the enthusiasm of the Crusaders returning from the Holy Land, gave a rise to devotion to the Passion of Jesus Christ.[1]

Many medieval prayers in honour of the Sacred Wounds, including some attributed to Clare of Assisi[2] have been preserved. St. Mechtilde and St. Gertrude of Helfta were devoted to the Holy Wounds, the latter saint reciting daily a prayer in honour of the 5466 wounds, which, according to a medieval tradition, were inflicted on Jesus during His Passion. In the fourteenth century it was customary in southern Germany to recite fifteen Pater Nosters each day (which thus amounted to 5475 in the course of a year) in memory of the Sacred Wounds.

While in the course of his Passion, Jesus suffered various wounds, such as those from the crown of thorns and from the scourging at the pillar, medieval popular piety focused upon the five wounds associated directly with Christ's crucifixion, i.e., the nail wounds on his hands and feet as well as the lance wound which pierced his side.

There was in the medieval Missals a special Mass in honour of Christ's Wounds, known as the Golden Mass, During its celebration five candles were always lighted and it was popularly held that if anyone should say or hear it on five consecutive days he should never suffer the pains of hell fire.[1]

The Dominican Rosary also helped to promote devotion to the Sacred Wounds, for while the fifty small beads refer to Mary, the five large beads and the corresponding Pater Nosters are intended to honour the Five Wounds of Christ. Again, in some places it was customary to ring a bell at noon on Fridays, to remind the faithful to recite five Paters and Aves in honour of the Holy Wounds.[1]

The wounds

The five wounds comprised one through each hand or wrist, one through each foot, and one to the chest.

- Two of the wounds were through either his hands or his wrists, where nails were inserted to fix Jesus to the cross-beam of the cross on which he was crucified. According to American expert in forensic medicine, Frederick T. Zugibe, the most plausible region for the nail entry site in the case of Jesus is the upper part of the palm angled toward the wrist since this area can easily support the weight of the body, assures no bones are broken, marks the location where most people believed it to be, accounts for where most of the stigmatists have displayed their wounds and it is where artists through the centuries have designated it. This position would result in apparent lengthening of the fingers of the hand because of nail compression.[3]

- Two were through the feet where the nail(s)[4] passed through both to the vertical beam.[5]

- The final wound was in the side of Jesus' chest, where, according to the New Testament, his body was pierced by the Holy Lance in order to be sure that he was dead. The Gospel of John states that blood and water poured out of this wound (John 19:34). Although the Gospels do not specify on which side he was wounded, it was conventionally shown in art as being on Jesus's proper right side, though some depictions, notably a number by Rubens, show it on the proper left.[6]

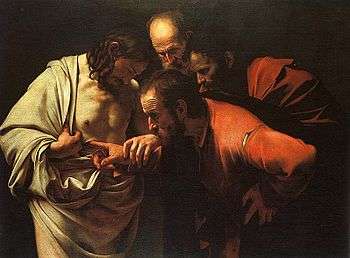

The examination of the wounds by "Doubting Thomas" the Apostle, reported only in the Gospel of John at John 20:24-29, was the focus of much commentary and often depicted in art, where the subject has the formal name of the Incredulity of Thomas.

Holy Wound devotions

In his 1761 book, The Passion and Death of Jesus Christ, Saint Alphonsus Maria de Liguori, founder of the Redemptorist Fathers, listed among various pious exercises, the Little Chaplet of the Five Wounds of Jesus Crucified[7]

The Passionist Chaplet of the Five Wounds was developed in Rome in 1821.[8] A corona of the Five Wounds was approved by the Holy See on 11 August 1823, and again in 1851. It consists of five divisions, each composed of five Glories in honour of Christ's Wounds and one Ave in commemoration of the Sorrowful Mother. The blessing of the beads is reserved to the Passionists.[1]

The Rosary of the Holy Wounds (also called the Chaplet of Holy Wounds), was first introduced at the beginning of the 20th century by the Venerable Sister Marie Martha Chambon, a lay Roman Catholic Sister of the Monastery of the Visitation Order in Chambéry, France.[9]

Symbolic use

As early as 1139 Afonso I of Portugal put the emblem of the five wounds on his coat of arms as king of Portugal.

The Cross of Jerusalem, or "Crusaders’ Cross", remembers the Five wounds through its five crosses. The Holy Wounds have been used as a symbol of Christianity. Participants in the Crusades would often wear the Jerusalem cross, an emblem representing the Holy Wounds; a version is still in use today in the flag of Georgia. The "Five Wounds" was the emblem of the "Pilgrimage of Grace", a northern English rebellion in response to Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries.

When consecrating an altar a number of Christian churches anoint it in five places, indicative of the Five Holy Wounds. Eastern Orthodox churches will sometimes have five domes on them, symbolizing the Five Holy Wounds, along with the alternate symbolism of Christ and the Four Evangelists.

In sacred music

The medieval poem Salve mundi salutare (also known as the Rhythmica oratio) was formerly ascribed to St. Bonaventure or Bernard of Clairvaux,[10] but now is thought more likely to have been written by the Cistercian abbot Arnulf of Leuven (d. 1250). A lengthy meditation upon the Passion of Christ, it is composed of seven parts, each pertaining to one of the members of Christ's crucified body.[11] Popular in the 17th-century, it was arranged as a cycle of seven cantatas in 1680 by Dieterich Buxtehude. His 1680 "Membra Jesu Nostri" is divided into seven parts, each addressed to a different member of Christ's crucified body: feet, knees, hands, side, breast, heart, and head framed by selected Old Testament verses containing prefigurements.

The cantata has come down to us more widely known as the hymn O Sacred Head Surrounded named for the closing stanza of poem addressed to Christ's head which begins "Salve caput cruentatum." Translated by Lutheran hymnist Paul Gerhardt, Johann Sebastian Bach arranged the melody and used five stanzas of the hymn in his "St Matthew Passion". Franz Liszt included an arrangement of this hymn at the sixth station, Saint Veronica wipes the Holy Face, in his Via Crucis (the Way of the Cross).

In art

In art the subject of Doubting Thomas, or the Incredulity of Saint Thomas, has been common since at least the early 6th century, when it appears in the mosaics at Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna,[12] and on the Monza ampullae. Among the most famous examples are the sculpted pair of Christ and St. Thomas by Andrea del Verrocchio (1467–1483) for the Orsanmichele in Florence and The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Caravaggio, now in Potsdam.

In the later Middle Ages Jesus with one side of his robe pulled back, displaying the wound in his side and his other four wounds (called the ostentatio vulnerum, "display of the wounds"), was taken from images with the Doubting Thomas and turned into a pose adopted by Jesus alone, who often places his own fingers into the wound in his side. This form became a common feature of single iconic figures of Jesus and subjects such as the Last Judgement (where Bamberg Cathedral has an early example of about 1235), Christ in Majesty, the Man of Sorrows and Christ with the Arma Christi, and was used to emphasize Christ's suffering as well as the fact of his Resurrection.[13]

| Part of a series on |

| Devotions to Christ of the Catholic Church |

|---|

| Devotions |

| Prayers |

|

|

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Holweck, Frederick. "The Five Sacred Wounds." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 1 Jun. 2013

- ↑ Fiege O. M. Cap., Marianus. Princess of Poverty, Saint Clare of Assisi, p.305, Poor Clares of the Monastery of S. Clare, Evansville, Indiana, 1900

- ↑ Zugibe M.D., Frederick T., "The Crucifixion of Jesus, Second Edition, Completely Revised and Expanded: A Forensic Inquiry" Publisher: M. Evans and Company, Inc.; 2nd edition (May 25, 2005)

- ↑ In Eastern Christianity, the crucificion is traditionally depicted with Jesus' feet side by side, and a separate nail for each; in Western Christianity, the crucifix usually shows the two feet placed one above the other, and both pierced by a single nail.

- ↑ Of all the thousands crucified by the Romans, skeletal remains of only one have so far been discovered by archeologists, and that one showed a nail piercing through the heel.

- ↑ Gurewich, Vladimir, "Rubens and the Wound in Christ's Side. A Postscript", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 26, No. 3/4 (1963), p. 358, The Warburg Institute, JSTOR

- ↑ Liguori, Alfonso Maria de, Saint. The Passion and Death of Jesus Christ, p.472, Benziger Brothers, New York, 1887

- ↑ Womack C.P.A., Rev. Fr. Warren. "The Passionist", Dec. 1951, pp. 270-274, 333-334

- ↑ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X

- ↑ Henry, Hugh. "Salve Mundi Salutare." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 2 Mar. 2015

- ↑ Snyder, Kerala. J., Dieterich Buxtehude: Organist in Lübeck, University Rochester Press, 1987 ISBN 9781580462532

- ↑ Soper, 188, listing several other early occurrences

- ↑ Schiller, Vol 2, 188-189, 202

Sources

- Kerr, Anne Cecil. Sister Mary Martha Chambon of the Visitation B. Herder Publishing, 1937

- Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II, 1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0853313245