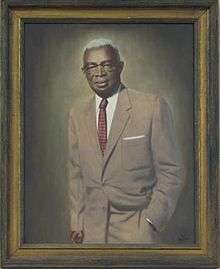

Z. Alexander Looby

Zephaniah Alexander Looby (April 8, 1899 – March 24, 1972) was a lawyer in Nashville, Tennessee who was active in the Civil Rights Movement. Born in the British West Indies, he immigrated to the United States at the age of 15. After working at a variety of jobs, he earned degrees at Howard University, Columbia University Law School, and New York University.

He settled in Nashville, Tennessee, where he built a law practice and taught at Fisk University. He is noted for being part of the defense team for 25 black men charged in attempted murder for the Columbia race riot of 1946 and winning acquittals for most, in the aftermath of the first major racial confrontation in the United States after World War II.[1][2] He participated in numerous other cases, including leading desegregation of schools in Nashville.[3]

Early life

Looby was born in Antigua. When he was five, his mother had died while giving birth to a sibling. His father died when Looby was a teenager. The youth moved to the United States in 1914 as an orphan when he was fifteen years old. After reaching the U.S., he worked various odd jobs, reading widely to educate himself.

Looby attended Howard University as an undergraduate and became a member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in 1922. He went on to earn a law degree in 1925 from Columbia University in New York City, and a doctorate in jurisprudence from New York University in 1926.[3]

Career

After graduating from New York University, Looby moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he started as an assistant professor at Fisk University, a historically black college.[3] In July 1928 he passed the Tennessee bar exam and opened his own practice. In 1932, he helped found the Kent College of Law in Nashville. This African-American night school admitted both men and women.

Looby was part of the defense team organized by the NAACP for black men charged in the Columbia race riot of 1946. After a physical confrontation in which a white man was wounded by a black, a white mob had gathered and there were rumors they planned to lynch the black veteran and his mother. Some whites drove around, shooting into the black business district of Columbia, Tennessee. African-American veterans and other men took up arms to defend their neighborhood. When police entered the area, in the confusion residents exchanged gunfire with police, wounding four with buckshot.[1]

The county sheriff called in the State Guard and Highway Patrol to control the mob. The State Guard refused to arm whites, which the Patrol requested. The next morning the Highway Patrol entered the black district without coordination and attacked and looted many businesses. Over the next day they arrested more than 100 blacks. Suspects were held and questioned without counsel. A few days later the Highway Patrol killed two black men and wounded a third in what the police said was an attempted escape by suspects as they were being taken from jail to the sheriff's office.[1]

Twenty-five blacks were charged in conjunction with the shootings. Looby worked with white attorney Maurice Weaver from Chattanooga and Thurgood Marshall of the Legal Defense and Educational Fund of the NAACP; the latter led the defense team. They won acquittals for 24 of the 25 men charged, and the last had his charges reduced.[2]

Avon N. Williams Jr., a cousin of Marshall, was also interested in the Civil Rights Movement. He joined Looby’s practice in order to help defend African Americans who were participating in the movement during the 1950s and 1960s.

As a young state senator in Nashville’s fifth ward, Ben West pushed for a charter reform in 1950 to allow local residents to elect city council members from single-member districts rather than through at-large voting. The latter system favored the white majority in the city and made it difficult for the sizeable African-American minority ever to elect candidates of their choice. With the change, African Americans began to elect some candidates. At that time, many black voters were still disenfranchised since the state had passed laws in the late 1880s to charge poll taxes and make voter registration and voting difficult.[4][4]

After the change to the charter, in May 1951 Looby was elected to the Nashville City Council, along with another lawyer, Robert Lillard. They were the first African Americans to be elected to the council since 1911. In 1953, the state passed a constitutional amendment to repeal the poll tax. This led to increased numbers of African Americans registering to vote statewide.

After the United States Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional, Looby filed a suit in Nashville on behalf of A.Z. Kelley. His son had been denied admission to a traditionally white school. Looby is credited with beginning the school desegregation movement in Nashville, which progressed more rapidly than in some areas of the South.

Beginning in February 1960, councilman Looby defended the students arrested in the Nashville sit-ins to achieve integration of public places. His law associates Avon Nyanza Williams and Robert E. Lillard also were part of the defense team.[5] As a result of Looby's support of the students, his house was dynamited by segregationists on April 19, 1960. The house was nearly destroyed by the powerful bomb, which also blew out 140 windows at nearby Meharry Medical College, resulting in minor injuries to students. Neither Looby nor his wife, Grafta Mosby Looby, was harmed in the bombing.

Afterward students from Fisk University led 2500 protesters on a silent walk to city hall, where they confronted Mayor Ben West. Diane Nash asked him, "Do you feel it is wrong to discriminate against a person solely on the basis of their race or color?" West said "yes,' later explaining, "It was a moral question – one that a man had to answer, not a politician."[5] By May of that year, lunch counters in Nashville were desegregated. By October Looby and his team gained dismissal of the charges against 91 students "for conspiracy to disrupt trade and commerce."[5]

Looby died on March 24, 1972, at Hubbard Hospital after a prolonged period of illness. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Nashville.[3]

Awards and recognition

- In 1976, the city government of Nashville named a new library and community center in Looby's honor.

- In 1978, the James C. Napier Lawyers Association changed its name to the Napier-Looby Bar Association, in honor of Looby and his accomplishments.[6]

- In 1982, the Nashville Bar Association posthumously awarded Looby membership; it had rejected him on racial grounds when he applied in the 1950s.

References

- 1 2 3 Dorothy Beeler, "Race Riot in Columbia, Tennessee/ February 25-27, 1946", Tennessee Historical Quarterly Vol. 39, No. 1 (Spring 1980), pp. 49-61, accessed 6 March 2015

- 1 2 Gilbert King, Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America, HarperCollins, 2012, pp. 8 and 14

- 1 2 3 4 Walter, Jeff (March 25, 2003). "Looby played vital role in Nashville's integration". The Tennessean.

- 1 2 Connie L. Lester, "Disfranchising laws", Tennessee Encyclopedia of Culture and History, 2011

- 1 2 3 "Timeline: The Civil Rights Movement in America", "This Honorable Body:" African American Legislators in 19th Century Tennessee, 2013, Tennessee Department of State

- ↑ "About the Napier-Looby Bar Association". Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- Sarvis, Will (2003). "Leaders in the Court and the Community: Z. Alexander Looby, Avon N. Williams, Jr., and the Legal Fight for Civil Rights in Tennessee, 1940-1970". Journal of African American History. 88 (1): 42–58. doi:10.2307/3559047.

- Halberstam, David (1999). The Children. Fawcett Books. ISBN 9780449004395.

- "About NLBA". Control Alt Designs. Retrieved 4 November 2013.