Zoar, Ohio

| Zoar, Ohio | |

|---|---|

| Village | |

|

Former canal tavern | |

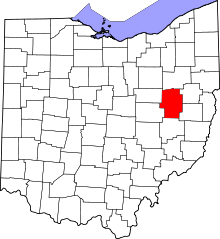

Location of Zoar, Ohio | |

Detailed map of Zoar | |

| Coordinates: 40°36′47″N 81°25′18″W / 40.61306°N 81.42167°WCoordinates: 40°36′47″N 81°25′18″W / 40.61306°N 81.42167°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Tuscarawas |

| Township | Lawrence |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 0.67 sq mi (1.74 km2) |

| • Land | 0.58 sq mi (1.50 km2) |

| • Water | 0.09 sq mi (0.23 km2) |

| Population (2010)[2] | |

| • Total | 169 |

| • Estimate (2012[3]) | 173 |

| • Density | 291.4/sq mi (112.5/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| ZIP code | 44697 |

| Area code(s) | 330 |

Zoar is a village in Tuscarawas County, Ohio, United States. The population was 169 at the 2010 census. The community was founded in 1817 by German religious dissenters as a utopian community, which survived until 1853.

Much of the village's early layout survives, as do many buildings from its utopian origins. Most of the community was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969 as the Zoar Historic District, and was designated a National Historic Landmark District in 2016.[4] Some of the historic buildings are now operated as museum properties.

History

Zoar was founded by German religious dissenters called the Society of Separatists of Zoar in 1817.[5] It was named after the Biblical village to which Lot and his family escaped from Sodom.[6] It was a communal society, with many German-style structures that have been restored and are part of the Zoar Village State Memorial. There are presently ten restored buildings. According to the Ohio Historical Society, Zoar is an island of Old-World charm in east-central Ohio.[7]

The Separatists, or Zoarites, emigrated from the kingdom of Württemberg in southwestern Germany due to religious oppression from the Lutheran church. Leading among their group were some natives of Rottenacker on the Danube. Having separated from the established church, their theology was based in part on the writings of Jakob Böhme. They did not practice baptism or confirmation and did not celebrate religious holidays except for the Sabbath. A central flower garden in Zoar is based on the Book of Revelation with a towering tree in the middle representing Christ and other elements surrounding it representing other allegorical elements.

The leader of the society was named Joseph Bimeler (also known as Joseph Bäumler or Bäumeler, born 1778), a pipemaker as well as teacher from Ulm. His charismatic leadership carried the village through a number of crises.

An early event critical to the success of the colony was the digging of the Ohio and Erie Canal. The Zoarites had purchased 5,000 acres (20 km2) of land sight unseen and used loans to pay for it. The loans were to be paid off by 1830. The Society struggled for many years to determine what products and services they could produce in their village to pay off the loans. The state of Ohio required some of the Zoarite land to be used as a right of way and offered the Zoarites an opportunity to assist in digging the canals for money. The state gave them a choice of digging it themselves for pay or having the state pay others to dig the canal. The Zoarites then spent several years in the 1820s digging the canal and thus were able to pay off their loans on time with much money to spare.

Bimeler's death on August 31, 1853 led to a slow decline in the cohesion of the village. By 1898, the village voted to disband the communal society and the property was divided among the remaining residents.

Geography

Zoar is located at 40°36′47″N 81°25′18″W / 40.61306°N 81.42167°W (40.613102, -81.421686),[8] along the Tuscarawas River.[9]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 0.67 square miles (1.74 km2), of which 0.58 square miles (1.50 km2) is land and 0.09 square miles (0.23 km2) is water.[1]

Zoar is located at Mile Post 84.5 on the main line of the Wheeling and Lake Erie Railway between Cleveland and Wheeling, West Virginia, which parallels the Tuscarawas River for much of its length.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 249 | — | |

| 1860 | 252 | 1.2% | |

| 1870 | 326 | 29.4% | |

| 1880 | 291 | −10.7% | |

| 1900 | 290 | — | |

| 1910 | 182 | −37.2% | |

| 1920 | 178 | −2.2% | |

| 1930 | 146 | −18.0% | |

| 1940 | 208 | 42.5% | |

| 1950 | 200 | −3.8% | |

| 1960 | 191 | −4.5% | |

| 1970 | 228 | 19.4% | |

| 1980 | 264 | 15.8% | |

| 1990 | 177 | −33.0% | |

| 2000 | 193 | 9.0% | |

| 2010 | 169 | −12.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 181 | [10] | 7.1% |

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 169 people, 77 households, and 58 families residing in the village. The population density was 291.4 inhabitants per square mile (112.5/km2). There were 85 housing units at an average density of 146.6 per square mile (56.6/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 98.2% White, 0.6% Asian, and 1.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.6% of the population.

There were 77 households of which 19.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 66.2% were married couples living together, 7.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 1.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 24.7% were non-families. 20.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 2.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.19 and the average family size was 2.50.

The median age in the village was 52.6 years. 10.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 6.5% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 14.8% were from 25 to 44; 42.6% were from 45 to 64; and 26% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the village was 52.1% male and 47.9% female.

2000 census

As of the census[12] of 2000, there were 193 people, 79 households, and 62 families residing in the village. The population density was 350.8 people per square mile (135.5/km²). There were 81 housing units at an average density of 147.2 per square mile (56.9/km²). The racial makeup of the village was 97.93% White, 1.04% Asian, and 1.04% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.52% of the population.

There were 79 households out of which 22.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 68.4% were married couples living together, 10.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 20.3% were non-families. 17.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 2.73.

In the village the population was spread out with 20.2% under the age of 18, 5.7% from 18 to 24, 18.7% from 25 to 44, 42.5% from 45 to 64, and 13.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 48 years. For every 100 females there were 89.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.8 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $46,964, and the median income for a family was $55,625. Males had a median income of $45,417 versus $33,750 for females. The per capita income for the village was $22,828. About 3.6% of families and 3.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.4% of those under the age of 18 and none of those 65 and older.

Flooding threat

The future of the village is threatened because a Tuscarawas River levee that protects the village has been given the lowest safety rating by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The village sits at the base of the levee, which was built by the Corps in 1936 as part of its water management program in the region.

With the levee in failing condition, the Corps was evaluating three alternatives:

- Repair the levee

- Purchase the village, tear it down, and let the area flood

- Relocate the village to higher ground.

The Zoar Village Government and the Zoar Community Association are working to preserve the Village where it stands and have created the Save Historic Zoar Association.[13]

Initial Corps estimates, as of mid-2012, put the cost of repairing the levee at about $130 million, slightly less than $1 million per resident. In June 2012 the National Trust for Historic Preservation placed Zoar on its annual list of "America's eleven most endangered historic places."[14]

In November 2013 the Corps, following further review, reclassified the levee's safety rating from 1 (lowest) to Dam Safety Action Classification 3, meaning the possibility of failure is moderate to high. An expedited full evaluation is to occur within a year. In so doing, the Corps also dropped the option of breaching the levee from the list of solutions being considered, and study options for repairing the existing levee, thereby significantly reducing the likelihood that the village will have to be destroyed or relocated.[15][16][17]

References

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- ↑ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "Secretary Jewell, Director Jarvis Announce 10 New National Historic Landmarks Illustrating America's Diverse History, Culture". Department of the Interior. November 2, 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ Mangus, Michael; Herman, Jennifer L. (2008). Ohio Encyclopedia. North American Book Dist LLC. p. 592. ISBN 978-1-878592-68-2.

- ↑ "Genesis 19". Bible.

- ↑ "The Ohio Historical Society, Zoar Village".

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ DeLorme (1991). Ohio Atlas & Gazetteer. Yarmouth, Maine: DeLorme. ISBN 0-89933-233-1.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Historic Zoar's survival hinges on levee". New Philadelphia Times Reporter. March 22, 2011.

- ↑ Ray Rivera (August 27, 2012). "Levee Needing Costly Repairs Lands Ohio Village on Endangered List". New York Times.

- ↑ Jon Baker (November 22, 2013). "Historic Zoar saved from levee breaching". TimesReporter.

- ↑ Alan Johnson (November 22, 2013). "Historic Ohio village to be spared". The Columbus Dispatch.

- ↑ Alan Johnson (November 23, 2013). "Levee near Zoar won't be removed". The Columbus Dispatch.

Further reading

- Fritz, Eberhard: Das Liederbuch des Ulmer Separatisten Michael Baeumler (1778–1853) aus Merklingen. Ein Separatist in Ulm und seine Beziehungen zu Rottenacker.In: Wolfgang Schürle (Hg.): Bausteine zur Geschichte 1. Kleinode aus vier Jahrhunderten. Ulm 2002. S. 125-145.

- Fritz, Eberhard: Roots of Zoar, Ohio, in early 19th century Württemberg: The Separatist group of Rottenacker and its Circle. Part one. Communal Societies 22/2002. p. 27-44. - Part two. Communal Societies 23/2003. p. 29-44.

- Woolson, Constance Fenimore. "The Happy Valley", Harper's Weekly, July 1870.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Separatists. |

- Ohio History: Zoar

- Ohio and Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary