1933 Cuba–Brownsville hurricane

| Category 5 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

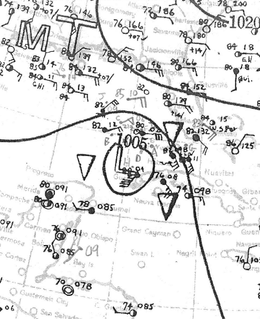

Surface weather analysis of the storm near Cuba | |

| Formed | August 22, 1933 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 5, 1933 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | < 930 mbar (hPa); 27.46 inHg |

| Fatalities | 179 total |

| Damage | $27.9 million (1933 USD) |

| Areas affected | Bahamas, Cuba, Florida, Texas, Tamaulipas |

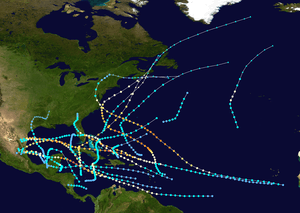

| Part of the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1933 Cuba–Brownsville hurricane was one of two storms in the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season to reach the intensity of a Category 5 strength on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. It formed on August 22 off the west coast of Africa, and for much of its duration it maintained a west-northwest track. The system intensified into a tropical storm on August 26 and into a hurricane on August 28. Passing north of the Lesser Antilles, the hurricane rapidly intensified as it approached the Turks and Caicos islands. It reached Category 5 status and its peak winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) on August 31. Subsequently, it weakened before striking northern Cuba on September 1 with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h). In the country, the hurricane left about 100,000 people homeless and killed over 70 people. Damage was heaviest near the storm's path, and the strong winds destroyed houses and left areas without power. Damage was estimated at $11 million.[nb 1]

After exiting from Cuba, the hurricane entered the Gulf of Mexico and restrengthened. On September 2, it re-attained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h). Initially the hurricane posed a threat to the area around Corpus Christi, Texas, and the local United States Weather Bureau forecaster advised people to stay away from the Texas coastline during the busy Labor Day Weekend. Officials declared martial law in the city and mandated evacuations. However, the hurricane turned more to the west and struck near Brownsville early on September 5 with winds estimated at 125 mph (205 km/h). It quickly dissipated after causing heavy damage in the Rio Grande Valley. High winds caused heavy damage to the citrus crop. The hurricane left $16.9 million in damage and 40 deaths in southern Texas.

Meteorological history

The origins of the hurricane were from a tropical disturbance near the west coast of Africa on August 20. Two days later, the system organized enough to be classified a tropical depression just southwest of Cape Verde. For the next few days, the system moved west-northwestward with little change in intensity. It is estimated the depression strengthened into a tropical storm on August 26, about halfway between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde. Initially, the storm was elongated, although beginning on August 28 it began to intensify more quickly. That night, the storm attained hurricane status, and many nearby ships reported gale force winds.[1]

On August 29, the hurricane passed north of the Lesser Antilles as it approached the southeastern Bahamas. It underwent rapid deepening: in a 24‑hour period beginning late on August 29, the winds increased from 105 mph (165 km/h) to 150 mph (240 km/h). It also became a small storm, as Grand Turk Island reported winds of 56 mph (90 km/h) while the hurricane passed slightly to the north on August 30. At 0130 UTC the next day, a ship near Mayaguana reported a barometric pressure of 930 mbar (27 inHg) and hurricane-force winds. The pressure would ordinarily suggest winds of 152 mph (245 km/h), but because it was not reported in the eye and the storm was smaller than normal, the winds were estimated at 160 mph (260 km/h). The hurricane's winds rank as a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, one of two such storms in the 1933 season.[1]

After maintaining peak winds for about 12 hours, the hurricane began weakening as it passed through the southern Bahamas. At around 1200 UTC on September 1, the hurricane made landfall on northern Cuba near Sagua La Grande, with winds of about 120 mph (190 km/h). The eye moved along the northern coast of Cuba, crossing over Matanzas. Shortly thereafter the storm exited into the Straits of Florida, and late on September 1 the hurricane passed about 16 mi (26 km) north of Havana. After entering the Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane restrengthened, and a ship reported a pressure of 948 mbar (28.0 inHg) late on September 2; this suggested winds of about 140 mph (230 km/h). The hurricane turned more to the west on September 3, and as it approached southern Texas it weakened slightly as it decelerated. At 0400 UTC on September 5, the hurricane made its final landfall on South Padre Island in southern Texas, with winds estimated at 125 mph (205 km/h). It quickly weakened over land as it crossed into northeastern Mexico, and the storm dissipated late on September 5.[1]

Impact

Throughout its path, the hurricane killed at least 179 people collectively in the Turks and Caicos Islands, Cuba, and south Texas.[2] It first affected the Turks and Caicos, producing winds of 54 mph (87 km/h) on Grand Turk.[3]

Before the hurricane struck Cuba, officials warned of the impending storm, and military workers warned people to remain indoors.[4] About 4,000 people evacuated the coastal town of Isabela on three trains specifically run for the residents. In Havana, business owners secured their properties in anticipation of the storm.[5] Most of the deaths from the hurricane occurred in northern Cuba. Winds of over 115 mph (185 km/h) affected the coastline, and Havana reported maximum winds of 94 mph (151 km/h).[1] There, the winds downed power lines and uprooted trees. High waves flooded six blocks of the city with up to 4 ft (1.2 m) of water, entering the cellars of some homes.[4] East of Havana in Cárdenas, high waves destroyed the aqueduct, while high winds severely damaged the local sugar industry. A nearby coastal town 20 mi (32 km) east of Cárdenas was described as being "virtually leveled by the storm" in news reports.[6] In Cienfuegos along the southern coast, the hurricane destroyed many ships and piers.[4] High waves washed four ships ashore, one of which damaged another ship.[7] High winds destroyed hundreds of houses and damaged many others along the storm's path.[8] About 100,000 people were left homeless, many of whom lacking food or medical supplies.[9] In the interior of the country, the hurricane dropped rainfall that flooded rivers and towns.[10] Damage was estimated at $11 million, and a report published in 2003 indicated that there were about 70 deaths in the country;[11] however, newspaper accounts from shortly after the hurricane indicated there were around 100 deaths.[12] After the storm, police officers were deployed to maintain order.[4] Officers shot and killed five people caught looting in Havana, although the deaths were not included in the overall death toll.[13] Officials deployed trucks to pick up wounded citizens.[14]

While the hurricane was over the Bahamas late on August 30, the United States Weather Bureau issued storm warnings for southern Florida. Two days later, the storm struck Cuba and passed south of the state, producing peak winds of 42 mph (68 km/h) in Key West.[3] The winds caused little damage; however, high waves destroyed a sea wall and washed onto a coastal roadway. High waves also sank a boat, killing three people.[15]

Three days before the hurricane made its final landfall, officials at the Weather Bureau in Brownsville issued a warning to all stations along the Texas coast, declaring that it was "uncertain where tropical storm in Gulf will reach coast line, but all persons should be warned to remain away from inaccessible places on Texas coast over week end." The early warning was to prevent travelers from being on the Texas beaches on Labor Day Weekend. As a result, an official at the Corpus Christi Weather Bureau office estimated that the warning "probably saved thousands of lives." Early on September 4 about a day before landfall, the Weather Bureau issued a hurricane warning from Corpus Christi to Freeport and storm warnings for other locations along the Texas coast. When the storm's westward motion became more apparent, the hurricane warning was dropped north of Corpus Christi and extended southward to Brownsville.[3] Officials in Corpus Christi declared martial law before the storm struck and ordered mandatory evacuations of low-lying areas. Shelters opened in the city, and many businesses closed.[16]

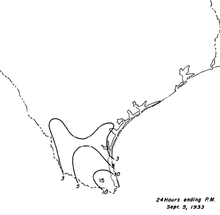

When the storm moved across the area, winds were estimated at 90 mph (140 km/h) in Brownsville,[3] with gusts to 125 mph (201 km/h).[17] High tides were reported along the coast,[15] and the storm surge reached 13 ft (4.0 m) near Brownsville. The tides flooded portions of Corpus Christi about 3 ft (0.91 m) deep, sinking boats and damaging piers. Storm-generated waves destroyed 20 buildings in one settlement. The storm destroyed the causeway from Padre Island to Flour Bluff, and there were over 40 breaches in the island,[17] some up to a mile wide.[16] The storm dropped heavy rainfall from southern Texas through northeastern Mexico,[18] peaking at over 15.0 in (380 mm) at a station near Mercedes; the total was one of four 24‑hour precipitation records set by the storm.[17] The rains from the storm and two previous hurricanes led to a large increase in tropical butterfly species across the area.[18] Throughout the Rio Grande Valley, the strong winds destroyed about 90% of the citrus crop.[17] Overall, the hurricane left $16.9 million in damage and 40 deaths, mostly in Cameron County.[15][17] However, none of the deaths were in Brownsville or Corpus Christi, which was credited to the advance warning.[3] Damage was less than expected in Corpus Christi, and many business owners who lost revenue sent letters of outcry to the Weather Bureau Headquarters; however, the Bureau determined that the evacuations and warnings were warranted given the storm's threat.[16]

See also

Notes

- ↑ All damage totals are in 1933 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1933) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ↑ Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Jack Beven (May 28, 1995). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996 (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC 47). Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 R. Hanson Weightman (September 1933). "Tropical Disturbances of August 1933" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 61 (8): 234–235. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..362D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<362:TSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- 1 2 3 4 "Death, Damage Left in Wake of Hurricane in Cuba". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. 1933-09-02. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "Havana Frightened". Gettysburg Press. Associated Press. 1933-09-01. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "Ships Warned of Hurricane at Sea". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. 1933-09-03. Retrieved 2012-06-13.

- ↑ "Four Ships Ask Help". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. 1933-09-01. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "60 Dead, Hurricane in Cuba". The Courier-Mail. Australian Press Association. 1933-09-04. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "100 Dead, Cuba Hurricane". The Courier-Mail. Australian Press Association. 1933-09-05. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ↑ "Storm Takes Toll in Cuba". Middlesboro Daily News. 1933-09-02. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Roger A. Pielke Jr.; Jose Rubiera; Christopher Landsea; Mario L. Fernández; Roberta Klein (August 2003). "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America and The Caribbean: Normalized Damage and Loss Potentials" (PDF). National Hazards Review. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 108. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ "Hurricane Threatens Texas Coastline; Thousands Flee". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. 1933-09-05. Retrieved 2012-06-13.

- ↑ "Storm Takes Toll in Cuba". Middlesboro Daily News. 1933-09-03. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "Scores Injured". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. United News. 1933-09-01. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- 1 2 3 Mary O. Souder (September 1933). "Severe Local Storms, September 1933" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 61 (9): 291. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..291.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<291:SLSS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- 1 2 3 Hurricane #11, 1933 (Report). Corpus Christi National Weather Service. February 2000. Archived from the original on November 8, 2008. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 David M. Roth (2010-02-04). Texas Hurricane History (PDF) (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. p. 42. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- 1 2 Raymond W. Neck (1977). "Effects of the 1933 Hurricanes on Butterflies of Central and Southern Texas" (PDF). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 31 (1): 67. Retrieved 2012-06-03.