Steam car

A steam car is a car (automobile) powered by a steam engine. [lower-alpha 1] A steam engine is an external combustion engine (ECE) where the fuel is combusted away from the engine, as opposed to an internal combustion engine (ICE) where the fuel is combusted within the engine. ECE have a lower thermal efficiency, but it is easier to regulate carbon monoxide production.

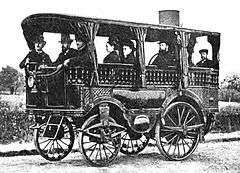

The first experimental steam powered vehicles were built in the 17th and 18th century, but it was not until after Richard Trevithick had developed the use of high-pressure steam, around 1800, that mobile steam engines became a practical proposition. By the 1850s it was viable to produce them on a commercial basis: steam road vehicles were used for many applications.

Development was hampered by adverse legislation from the 1830s and then the rapid development of internal combustion engine technology in the 1900s, leading to their commercial demise. Relatively few steam powered vehicles remained in use after the Second World War. Many of these vehicles were acquired by enthusiasts for preservation.

The search for renewable energy sources, has led to an occasional resurgence of interest in using steam power for road vehicles.

Technology

A steam engine is an external combustion engine (ECE: the fuel is combusted away from the engine), as opposed to an internal combustion engine (ICE: the fuel is combusted within the engine). While gasoline-powered ICE cars have an operational thermal efficiency of 15% to 30%, early automotive steam units were capable of only about half this efficiency. A significant benefit of the ECE is that the fuel burner can be configured for very low emissions of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and unburned carbon in the exhaust, thus avoiding pollution.

The greatest technical challenges to the steam car have focused on its boiler. This represents much of the total mass of the vehicle, making the car heavy (an internal combustion-engined car requires no boiler), and requires careful attention from the driver, although even the cars of 1900 had considerable automation to manage this. The single largest restriction is the need to supply feedwater to the boiler. This must either be carried and frequently replenished, or the car must also be fitted with a condenser, a further weight and inconvenience.

Steam-powered and electric cars outsold gasoline-powered ones in many US states prior to the invention of the electric starter, since internal combustion cars relied on a hand crank to start the engine, which was difficult and occasionally dangerous to use, as improper cranking could cause a backfire capable of breaking the arm of the operator. Electric cars were popular to some extent, but had a short range, and could not be charged on the road if the batteries ran low.

Early steam cars, once working pressure was attained, could be instantly driven off with high acceleration; but they typically take several minutes to start from cold, plus time to get the burner to operating temperature. To overcome this, development has been directed toward flash boilers, which heat a much smaller quantity of water to get the vehicle started, and, in the case of Doble cars, spark ignition diesel burners.

The steam car does have advantages over internal combustion-powered cars, although most of these are now less important than in the early 20th century. The engine (excluding the boiler) is smaller and lighter than an internal combustion engine. It is also better suited to the speed and torque characteristics of the axle, thus avoiding the need for the heavy and complex transmission required for an internal combustion engine. The car is also quieter, even without a silencer.

History

Early History

There is an unsubstantiated story that a pair of Yorkshiremen, engineer Robert Fourness and his cousin, physician James Ashworth had a steam carriage running in 1788, after being granted a British Patent, No.1674 of December 1788. An illustration of it even appeared in Hergé's book Tintin raconte l'Histoire de l'Automobile (Casterman, 1953). The first substantiated steam carriage for personal use was that of Josef Božek in 1815.[2] He was followed by Thomas Blanchard of Massachusetts in 1825.[3] Over thirty years passed before there was a flurry of steam cars from 1859 onwards with Dugeon, Roper and Spenser from the United States, Thomes Rickett, Austin, Catley and Ayres from England, and Innocenzo Manzetti from Italy being the earliest. Others followed with the first Canadian, Henry Taylor in 1867, Amédée Bollée and Louis Lejeune of France in 1878, and Rene Thury of Switzerland in 1879.

The 1880s saw the rise of the first larger scale manufacturers, particularly in France, the first being Bollée (1878) followed by De Dion-Bouton (1883), Whitney of East Boston (1885), Ransom E. Olds (1886), Serpollet (1887), and Peugeot (1889).

This early period also saw the first repossession of an automobile in 1867 and the first getaway car the same year - both by Francis Curtis of Newburyport, Massachusetts.[4]

1890s commercial manufacture

The 1890s were dominated by the formation of numerous car manufacturing companies. The internal combustion engine was in its infancy, whereas steam power was well established. Electric powered cars were becoming available but suffered from their inability to travel longer distances.

The majority of steam powered car manufacturers from this period were from the United States. The more notable of these were Clark from 1895 to 1909, Locomobile from 1899 to 1903 when it switched to petrol engines, and Stanley from 1897 to 1924. As well as England and France, other countries also made attempts to manufacture steam cars; Cederholm of Sweden (1892), Malevez of Belgium (1898-1905), Schöche of Germany (1895), and Herbert Thomson of Australia (1896-1901)

Of all the new manufacturers from the 1890s only four continued to make steam cars after 1910. They were Stanley (to 1924), and Waverley (to 1916) of the United States, Buard of France (to 1914), and Miesse of Belgium (to 1926).

Volume production 1900 to 1913

There were a large number of new companies formed in the period from 1898 to 1905. Steam cars outnumbered other forms of propulsion among very early cars. In the U.S. in 1902, 485 of 909 new car registrations were steamers.[5] From 1899 Mobile had ten branches and 58 dealers across the U.S. The center of U.S. steamer production was New England, where 38 of the 84 manufacturers were located. Examples include White (Cleveland), Eclipse (Easton, Massachusetts), Cotta (Lanark, Illinois), Crouch (New Brighton, Pennsylvania), Hood (Danvers, Massachusetts; lasted just one month), Kidder (New Haven, Connecticut), Century (Syracuse, New York), and Skene (Lewiston, Maine; the company built everything but the tires). By 1903, 43 of them were gone and by the end of 1910 of those companies that were started in the decade those left were White which lasted to 1911, Conrad which lasted to 1924, Turner-Miesse of England which lasted to 1913, Morriss to 1912, Doble to 1930, Rutherford to 1912, and Pearson-Cox to 1916.

Assembly-line mass production by Henry Ford dramatically reduced the cost of owning a conventional automobile, was also a strong factor in the steam car's demise as the Model T was both cheap and reliable. Additionally, during the 'heyday' of steam cars, the internal combustion engine made steady gains in efficiency, matching and then surpassing the efficiency of a steam engine when the weight of a boiler is factored in.

Decline 1914 to 1939

With the introduction of the electric starter, the internal combustion engine became more popular than steam, but the internal combustion engine was not necessarily superior in performance, range, fuel economy and emissions. Some steam enthusiasts feel steam has not received its share of attention in the field of automobile efficiency.[6]

Apart from Brooks of Canada, all the steam car manufacturers that commenced between 1916 and 1926 were in the United States. Endurance (1924-1925) were the last steam car manufacturer to commence operations. American/Derr continued retrofitting production cars of various makes with steam engines, and Doble was the last steam car manufacturer. They ceased business in 1930.

Resurgence - enthusiasts, air pollution, and fuel crises

From the 1940s various steam cars were constructed, usually by enthusiasts. Among those mentioned were Charles Keen, Cal Williams' 1950 Ford Conversion, Forrest R Detrick's 1957 Detrick S-101 prototype, and Harry Peterson's Stanley powered Peterson.[7] The Detrick was constructed by Detrick, William H Mehrling, and Lee Gaeke who designed the engine based on a Stanley.[8][9]

Charles Keen began constructing a steam car in 1940 with the intention of restarting steam car manufacturing. Keen's family had a long history of involvement with steam propulsion going back to his great great grandfather in the 1830s, who helped build early steam locomotives. His first car, a Plymouth Coupe used a Stanley engine. In 1948/1949 Keen employed Abner Doble to create a more powerful steam engine, a v4. He used this in La Dawri Victress S4 bodied sports car. Both these cars are still in existence.[10] Keen died in 1969 before completing a further car. His papers and patterns were destroyed at that time.[11]

In the 1950s the only manufacturer to investigate steam cars was Paxton. Abner Doble developed the Doble Ultimax engine for the Paxton Phoenix steam car, built by the Paxton Engineering Division of McCulloch Motors Corporation, Los Angeles. The engines sustained maximum power was 120 bhp (89 kW). A Ford Coupe was used a test-bed for the engine.[12] The project was eventually dropped in 1954.[13]

In 1957 Williams Engine Company Incorporated of Ambler began offering steam engine conversions for existing production cars. When air pollution became a significant issues for California in the mid-1960s the state encouraged investigation into the use of steam powered cars. The fuel crises of the early 1970s prompted further work. None of this work resulted in renewed steam car manufacturing.

Steam car remain the domain of enthusiasts, occasional experimentation by manufacturers, and those wishing to establish steam powered land speed records.

Impact of Californian Legislation

In 1967 California established the California Air Resources Board and began to implement legislation to dramatically reduce exhaust emissions. This prompted renewed interest in alternative fuels for motor vehicles and a resurgence of interest in steam-powered cars in the state.

The idea for having patrol cars fitted with steam engines stemmed for an informal meeting in March 1968 of members of the California Assembly Transportation Committee. In the discussion, Karsten Vieg, a lawyer attached to the Committee, suggested that six cars be fitted with steam engines for testing by California District Police Chiefs. A bill was passed by the legislature to fund the trial.[14]

In 1969 the California Highway Patrol initiated the project under Inspector David S Luethje to investigate the feasibility of using steam engined cars. Initially General Motors had agreed to pay a selected vendor $20,000 toward the cost of developing an Rankine cycle engine, and up to $100,000 for outfitting six Oldsmobile Delmont 88's as operational patrol vehicles. This deal fell through because the Rankine engine manufacturers rejected the General Motors offer.[15]

The plan was revised and two 1969 Dodge Polara's were to be retro-fitted with steam engines for testing. One car was to be modified by Don Johnson of Thermodynamic Systems Inc and the other by industrialist, William P Lear's, Lear Motors Incorporated. At the time the California State Legislature was introducing strict pollution control regulations for automobiles and the Chair of the Assembly Transportation Committee, John Francis Foran, was supportive of the idea. The Committee also was proposing to test four steam-powered buses in the San Francisco Bay area that year.[16]

Instead of a Polara, Thermodynamic Systems (later called General Steam Corp), were given a late model Oldsmobile Delmont 88. Lear's were given a Polara but it does not appear to have been built. Both firms were given 6 months to complete their projects with Lear's being due for completion on 1 August 1969. Neither car had been completed by the due date and in November 1969 Lear was reported as saying the car would be ready in 3 months.[17] Lear's only known retrofit was a Chevrolet Monte Carlo unrelated to the project. As for the project, it seems to have never been completed with Lear pulling out by December.[18][19][20][21]

In 1969 the National Air Pollution Control Administration announced a competition for a contract to design a practical passenger-car steam engine. Five firms entered. They were the consortium of Planning Research Corporation and STP Corporation; Battelle Memorial Institute, Columbus, Ohio; Continental Motors Corporation, Detroit; Vought Aeronautical Division of Ling-Temco-Vought, Dallas; and Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, Massachusetts.[22]

General Motors introduced two experimental steam-powered cars in 1969. One was the SE 124 based on a converted Chevrolet Chevelle and the other was designated SE 101 based on the Pontiac Grand Prix. The SE 124 had its standard gasoline engine replaced with a 50 hp power Besler steam engine, using the 1920 Doble patents; the SE 101 was fitted with a 160 hp steam engine developed by GM Engineering.[23]

In October 1969, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology put out a challenge for a race August 1970 from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Pasadena, California for any college that wanted to participate in. The race was open for electric, steam, turbine power, and internal combustion engines: liquid-fueled, gaseous-fueled engines, and hybrids.[24] Two steam-powered cars entered the race. University of California, San Diego's modified AMC Javelin and Worcester Polytechnic Institute's converted 1970 Chevrolet Chevelle called the tea kettle.[24] Both dropped out on the second day of the race.[25]

The California Assembly passed legislation in 1972 to contract two companies to develop steam-powered cars. They were Aerojet Liquid Rocket Company of Sacramento and Steam Power Systems of San Diego. Aerojet installed a steam turbine into a Chevrolet Vega, while Steam Power Systems built the Dutcher, a car named after the company's founder, Cornelius Dutcher. Both cars were tested by 1974 but neither car went into production. The Dutcher is on display at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles.[26]

Indy Cars

Both Johnson and Lear had contemplated constructing steam-powered cars for the Indy 500, Johnson first in the early 1960s when with Controlled Steam Dynamics and in 1968 with Thermodynamic Systems and Lear in 1969. A third steam racing car was contemplated by a consortium of Planning Research Corporation and Andy Granatelli of STP Corporation. Lear proceeded with the idea and constructed a car, but ran out of funds, while trying to develop the engine. The car is thought to be at the National Automobile and Truck Museum of the United States in Auburn, Indiana. Johnson was also noted as working on a steam-powered helicopter.[27]

William D Thompson, 69-year-old retired San Diego automotive engineer, also announced he planned to enter a steam-powered race car. Thompson was working on a $35,000 steam-powered luxury car and he intended to use the car's engine in the race car. He had claimed that he had almost 250 orders for his cars.[28] By comparison Rolls Royce's cost about $17,000 at that time.[29]

Donald Healey

With Lear pulling out of attempting to make steam car, Donald Healey decided to make a basic steam-car technology more in line with Stanley or Doble and aimed at enthusiasts. He planned to have the car in production by 1971.[30]

Ted Pritchard Falcon

Edward Pritchard created a steam-powered 1963 model Ford Falcon in 1972. It was evaluated by the Australian Federal Government and was also taken to the United States for promotional purposes.[31]

Saab steam car and Ranotor

As a result of the 1973 oil crisis, SAAB started a project in 1974 codenamed ULF[32] headed by Dr. Ove Platell[33] which made a prototype steam-powered car. The engine used an electronically controlled 28-pound multi-parallel-circuit steam generator with 1-millimetre-bore tubing and 16 gallons per hour firing rate which was intended to produce 160 hp (119 kW) continuous power,[34] and was about the same size as a standard car battery. Lengthy start-up times were avoided by using air compressed and stored when the car was running to power the car upon starting until adequate steam pressure was built up. The engine used a conical rotary valve made from pure boron nitride. To conserve water, a hermetically sealed water system was used.

The project was cancelled and the project engineer, Ove Platell, started a company Ranotor with his son Peter Platell to continue its development. Ranotor is developing a steam hybrid that uses the exhaust heat from an ordinary petrol engine to power a small steam engine, with the aim of reducing fuel consumption by 20%.[33] In 2008 truck manufacturers Scania and Volvo were said to be interested in the project.[35]

Pelland Steamer

In 1974, the British designer Peter Pellandine produced the first Pelland Steamer to a contract with the South Australian Government. It had a fibreglass monocoque chassis (based on the internal combustion-engined Pelland Sports) and used a twin-cylinder double-acting compound engine. It has been preserved at the National Motor Museum at Birdwood, South Australia.

In 1977 the Pelland Mk II Steam Car was built, this time by Pelland Engineering in the UK. It had a three-cylinder double-acting engine in a 'broad-arrow' configuration, mounted in a tubular steel chassis with a Kevlar body, giving a gross weight of just 1,050 lb (476 kg). Uncomplicated and robust, the steam engine was claimed to give trouble-free, efficient performance. It had huge torque (1,100 ft·lbf or 1,500 N·m) at zero engine revs, and could accelerate from 0 to 60 mph (0 to 97 km/h) in under 8 seconds.

Pellandine made several attempts to break the land speed record for steam power, but was thwarted by technical issues. Pellandine moved back to Australia in the 1990s where he continued to develop the Steamer. The latest version is the Mark IV.

Enginion Steamcell

From 1996, a R&D subsidiary of the Volkswagen group called Enginion AG was developing a system called ZEE (Zero Emissions Engine). It produced steam almost instantly without an open flame, and took 30 seconds to reach maximum power from a cold start. Their third prototype, EZEE03, was a three-cylinder unit meant to fit in a Škoda Fabia automobile. The EZEE03 was described as having a "two-stroke" (i.e. single-acting) engine of 1,000 cc (61 cu in) displacement, producing up to 220 hp (164 kW) (500 N·m or 369 ft·lbf).[36] Exhaust emissions were said to be far below the SULEV standard. It had an oilless engine with ceramic cylinder linings using steam instead of oil as a lubricant. However, Enginion found that the market was not ready for steam cars, so they opted instead to develop the Steamcell power generator/heating system based on similar technology.[37]

Notable manufacturers

Cederholm brothers

In 1892, painter Jöns Cederholm and his brother, André, a blacksmith, designed their first steam car, a two-seater, introducing a condenser in 1894. They planned to use it for transportation between their home in Ystad and their summer house outside town. Unfortunately the automobile was destroyed in Sweden's first automobile accident but the Cederholm brothers soon built a second, improved version of their steam car reusing many parts from the first one.[5][38] The car is preserved in a museum in Skurup.

Locomobile Runabout

What is considered by many to be the first marketable popular steam car appeared in 1899 from the Locomobile Company of America, located in Watertown, Massachusetts and from 1900 in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Locomobile manufactured several thousand of its Runabout model in the period 1899-1903, designed around a motor design leased from the Stanley Steamer Company. The company ceased producing steam cars in 1903 and changed to limited-production, internal combustion powered luxury automobiles. In 1922 it was acquired by Durant Motors and discontinued with the failure of the parent company in 1929.[39]

Stanley Steamer

Perhaps the best-known and best-selling steam car was the Stanley Steamer, produced from 1896 to 1924. Between 1899 and 1905, Stanley outsold all gasoline-powered cars, and was second only to the electric cars of the Columbia Automobile Company in the US.[5] It used a compact fire-tube boiler to power a simple double-acting two-cylinder engine. Because of the phenomenal torque available at all engine speeds, the steam car's engine was typically geared directly to the rear axle, with no clutch or variable speed transmission required. Until 1914, Stanley steam cars vented their exhaust steam directly to the atmosphere, necessitating frequent refilling of the water tank; after 1914, all Stanleys were fitted with a condenser, which considerably reduced their water consumption.

In 1906 the Land Speed Record was broken by a Stanley steam car, piloted by Fred Marriott, which achieved 127 mph (204 km/h) at Ormond Beach, Florida. This annual week-long "Speed Week" was the forerunner of today's Daytona 500. This record was not exceeded by any car until 1910.

Doble Steam Car

Attempts were made to bring more advanced steam cars on the market, the most remarkable being the Doble Steam Car[40] which shortened start-up time very noticeably by incorporating a highly efficient monotube steam generator to heat a much smaller quantity of water along with effective automation of burner and water feed control. By 1923, Doble's steam cars could be started from cold with the turn of a key and driven off in 40 seconds or less. When the boiler had achieved maximum working pressure, the burner would cut out until pressure had fallen to a minimum level, whereupon it would re-ignite; by this means the car could achieve around 15 miles per gallon (18.8 litres/100 km) of kerosene despite its weight in excess of 5,000 lb (2,268 kg). Ultimately, despite their undoubted qualities, Doble cars failed due to poor company organisation and high initial cost.

Toledo Steam Carriage

.jpg)

In 1900 the American Bicycle Co. of Toledo, Ohio created a 6.25 hp Toledo Steam Carriage (a description from the Horseless Age, December 1900). The American Bicycle Co was one of the enterprises within Col. Albert Pope's large conglomerate of bicycle and motor vehicles manufacturers. The Toledo Steam Carriage was a very well-made, high-quality machine where every component, bar the tires, bell, instruments and lights were made within the dedicated 245,000 sq ft factory in Toledo, Ohio. The Toledo is considered to be one of the best steam cars produced at the time. The engine was particularly robust and the 2, 3" diameter x 4" stoke pistons employed piston style valves instead of 'D' valves thus insuring better balance and reduced leakage of steam. In September 1901 two Toledo steamers, one model B (a model A machine 1,000 to 2,000 pounds or 454 to 907 kilograms but with the foul-weather gear designating it as a model B) and one class E (public delivery vehicle), were entered by the American Bicycle Co. into the New York to Buffalo Endurance Contest of mid-September 1901. There were 36 cars in class B and three in class E; the class B Toledo won the Grosse Point race. on 4 January 1902 a specially built Toledo steam carriage was the first automobile to forge a trail from Flagstaff, Arizona to the South Rim of The Grand Canyon, a distance of 67 miles. As a publicity exercise the trip was to assess the potential of starting a steam bus service but the anticipated afternoon journey took three days due to problems with supplies of the wrong fuel. Though the Toledo towed a trailer filled with additional water and fuel supplies the four participants omitted to take any food; one, the journalist Winfield Hoggaboon wrote up an amusing article in the Los Angeles Herald two weeks later. The previous December, on the 19th 1901 the company changed from the American Bicycle Company to the newly formed International Motor Car Company to concentrate on steam and gasoline driven models with electric vehicles being made by the separate Waverly Electric Co. Both steam and gasoline models were manufactured but as the public favoured the gasoline models and steam carriage sales were slow steam carriage production ceased in July 1902 and gasoline-driven models were then made under the name Pope-Toledo. Total production of the steamers was between 285 and 325 units, as confirmed by a letter from the International Motor Car Co book keeper to the firms' accountant in June 1902.

White Steamer

The White Steamer was manufactured in Cleveland, Ohio from 1900 until 1910 by the White Motor Company.

Endurance steam car

The Endurance Steam Car was a steam car manufactured in the United States from 1922 until 1924. The company had its origins in the Coats Steam Car and began production on the East Coast before shifting operations to Los Angeles in 1924. There, one single touring car was made using a 1923 Elcar 6-60 body before the factory moved again, this time to Dayton, Ohio where one more car was built, a sedan, before the company folded.[41][42]

Land speed record attempts

The land speed record for Steam powered cars stood from 1906 when a Stanley steam car, driven by Fred Marriott, which achieved 127 mph (204 km/h) at Ormond Beach, Florida. Despite several attempts to break the record it stood until 25 August 2009 when Team Inspiration of the British Steam Car Challenge set a new speed record of 139.843 mph (225.055 km/h). A second attempt by Don Wales on 26 August achieved an average speed of 238.679 km/h (148.308 mph).

Autocoast Vaporizer

Ernest Kanzler, the owner of Autocoast approached Ross (Skip) Hedrick in the fall of 1968 with the idea of installing a steam engine in Hedrick's 1964 Indy car for an attempt at the 1906 steam car record. Hedrick and Richard J Smith joined Autocoast to design the engine. The car was readied for the 1969 Bonneville speed week, but was unable to run because an unexpected rain-storm made the salt flats too soggy.[43]

Barber-Nichols

In 1985 Barber-Nichols Engineering of Denver used a steam turbine they had designed for Lear and the Los Angeles city bus program to attempt to gain the steam-powered land speed record. The car was run at Speed Week on the Bonneville Salt Flats over a period of several years, eventually reaching a measured speed of 145.607 mph one pass. A fire prevented the return run, and the speed was not recognized by the FIA.[44] FIA land speed records are based on an average of two runs (called 'passes') in opposite directions, taken within an hour of each other.

British Steam Car Challenge

On 25 August 2009, Team Inspiration of the British Steam Car Challenge broke the long-standing record for a steam vehicle set by a Stanley Steamer in 1906, setting a new speed record of 139.843 mph (225.055 km/h)[45][46] at the Edwards Air Force Base, in the Mojave Desert of California. This was the longest standing automotive record in the world. It had been held for over 100 years. The car was driven by Charles Burnett III and reached a maximum speed of 136.103 mph (219.037 km/h) on the first run and 151.085 mph (243.148 km/h) on the second.

On August 26, 2009 the same car, driven this time by Don Wales, the grandson of Sir Malcolm Campbell, broke a second record by achieving an average speed of 238.679 km/h (148.308 mph) over two consecutive runs over a measured kilometre. This was also recorded and has since been ratified by the FIA.

Steam Speed America

On 6 September 2014 Chuk Williams of Steam Speed America attempted to break the current world record in their steam-powered streamliner. The car reached 147 mph on its first run, but flipped and crashed when its braking chutes failed to open, Williams was injured in the accident and the car severely damaged.[47]

In popular culture

- Keith Roberts' Alternate history novel Pavane makes many references to steam land transport. In this alternate history, the death of Queen Elizabeth I in 1588 allows the Catholic Church to dominate world history, and the Index Prohibitorum includes petrol vehicles with engines larger than 100cc. The first chapter of the novel (set in 1968 through 1985) first describes steam transports made by Foden. In the last chapter, Corfe Gate reference is made to 100cc petrol powered 'Butterfly Cars' which rely as much on wind power as petrol engines for motive power. In addition, one of the knights of the castle is known to own a Steam Car – specifically, a Bentley, which needs his tending during harsh winters to 'prevent the block from freezing and breaking'.

- In Ward Moore's alternate history novella Bring the Jubilee, "trackless locomotives" referred to as "minibiles" are used in wealthy nations for personal transportation. In this world, internal combustion was never discovered and machines are always powered by steam.

- In another 'alternate history' novel The Two Georges, the authors Harry Turtledove and Richard Dreyfuss describe a North America where steam cars are generally used and Richard Nixon is a used car dealer.

- Specific makes of steam car (such as Locomobile) feature in other novels, such as The Chase by Clive Cussler.

- In Meredith Willson's The Music Man, conman Harold Hill reveals that he used to be in the steam automobile business until "someone actually invented one."

- In the movie Cars, Stanley Steamer is the founder of the town of Radiator Springs.

- The novel The Authorities, by Scott Meyer, features an 80's model passenger van that had been retrofitted with a steam-powered engine by a fictional manufacturer of steam engines. The engine provided so much torque that driving the van without squealing the tires was virtually impossible, while requiring only occasional battery recharging, water refilling, and periodic descaling.

- In various steampunk novels, such as The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, steam technology is widely used, including steam cars.

See also

References

- ↑ A car is defined as a wheeled, self-powered motor vehicle used for transportation and a product of the automotive industry. Most definitions of the term specify that cars are designed to run primarily on roads, to have seating for one to eight people, to typically have four wheels with tyres, and to be constructed principally for the transport of people rather than goods.[1]

- ↑ Fowler, H.W.; Fowler, F.G., eds. (1976). Pocket Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198611134.

- ↑ Wayback |date=20051124040052 |url=http://www.ntm.cz/ntext/ak-42-b.htm |title=Short Biography

- ↑ http://www.forgeofinnovation.org/Springfield_Armory_1812-1865/Chronology/nonFlash.html

- ↑ http://www.earlyamericanautomobiles.com/americanautomobiles2.htm retrieved 3 July 2015

- 1 2 3 Georgano, G.N. (1985). Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886-1930. London: Grange-Universal.

- ↑ "Modern Steam". Stanleysteamers.com. 2001-02-23. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ Steam Lore, Stanley W Ellis, The Bulb Horn, Vol. 18 No. 4, October 1957, Veteran Motor Car Club of America. Retrieved June 23, 2015

- ↑ "All steamed up to save gas". The Austin Daily Herald. January 31, 1958. p. 22. Retrieved June 23, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ http://www.stanleyregister.net/tours/1957Kent.html

- ↑ Charles Keen and his steamliners, The Steam Automobile, Vol 7 No 2, Summer 1965, p20

- ↑ http://www.steamautomobile.com/ForuM/read.php?1,15914

- ↑ A Modern Automotive Steam Power Plant Part IV—James L. Dooley, Vice President, McCulloch Corp, The Steam Automobile, Vol 5 No 3, 1963, page 12

- ↑ "The True Story of the Paxton Phoenix". Road and Track: 13–18. April 1957.

- ↑ Birth of the Steam Bus, S S Mine, The Steam Automobile, Vol 13 No 4, 1971, Chicargo, Illinous, page 3

- ↑ https://bulk.resource.org/courts.gov/juris/j1441_03.sgml

- ↑ Article by Don C Woodward, The Deseret News, 17 September 1969, page 7

- ↑ Article, The Tuscaloosa News, 19 November 1969, page 4

- ↑ Steam Powered Car Tesing to Begin, St Petersburg Times, 28 July 1969, page 25

- ↑ Article, Reading Eagle, 27 February 1969, page 32

- ↑ http://blog.hemmings.com/index.php/2011/06/07/gettin-steamed-on-the-bus/

- ↑ "Steam car fizzles". Wilmington News Journal. December 19, 1969. p. 4. Retrieved June 26, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Anti-pollution efforts revive interest in steamers, The Sunday News and Tribune, 24 August 1969, Page 5

- ↑ "GM Takes Its Wraps Off Its Steam Cars." Popular Science, July 1969, p. 84-85.

- 1 2 http://blog.hemmings.com/index.php/tag/steam/#sthash.PlXh9JwT.dpuf

- ↑ "Steam cars drop out of "clean" race". Bevidere Daily Republican. August 25, 1970. p. 8. Retrieved June 26, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ On the Road – Peterson Museum, June 26, 2007, retrieved 25 June 2015

- ↑ Article, Arizona Republic, 9 March 1969, Page 68

- ↑ "Wayne Panter - Steam, electric auto era looms, sometime". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. January 23, 1969. p. 67. Retrieved June 26, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Senate seeks answers to auto repair riddles". Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph. January 1, 1969. p. 52. Retrieved June 26, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Lear gives up on steam-powered car". The Newark Advocate. November 26, 1970. p. 17. Retrieved June 26, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Edward Pritchard of Australia Brings Modern Steam Car to America, The Steam Automobile, Vol 15 No 1, 1973, pages 7-8

- ↑ The Steam Automobile: Is The Steam Engine the Prime Mover of the Future?

- 1 2 Teknikens Värld: Ånghybridmotorn kan snart vara här

- ↑ Popular Science: Saab Tests Steam Power for Small Cars

- ↑ http://www.nordicgreen.net/startups/article/ranotor-develop-steam-engine-powered-hybrid-trucks-together-scania-and-volv

- ↑ "Feature Article – Clean & "Ezee" - 07/01". Autofieldguide.com. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ "Ghost in the machine". Newscientist.com. 2001-12-15. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ Barbro Brusell, Annette Rosengren (1997). Drömmen om bilen. Stockholm, Sweden: Nordiska Museet. ISBN 91-7108-411-8.

- ↑ Kimes, Beverly Rae (editor) and Clark, Henry Austin, jr., The Standard Catalogue of American Cars 1805-1942, 2nd edition, Krause Publications (1989), ISBN 0-87341-111-0

- ↑ Walton, J.N. (1965–1974). "Doble Steam Cars, Buses, Lorries, and Railcars". Light Steam Power. Isle of Man, UK.

- ↑ David Burgess Wise. The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Automobile.

- ↑ The good years, Elcar and Pratt Automobiles: The Complete History, William S Locke, McFarland, 2000, page 80, ISBN 0786432543, 9780786432547

- ↑ "Beach car builder, driver steamed up - ready to go". Independent Press-Telegram. November 30, 1969. p. 26. Retrieved June 26, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Rules - The Steam Car Club of Great Britain, retrieved 24 June 2015

- ↑ "The British Steam Car Challenge". Steamcar.co.uk. 1985-08-18. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ "UK team breaks steam car record". BBC News online. 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ Chuk Williams Steam Speed America at Bonneville, Ken Helmick, Steam Automobile Bulletin, Vol 28 No 6, November–December 2014, page 4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steam cars. |

- Hybrid-Vehicle.org: The Steamers

- The Steam Car Club of Great Britain

- Technical website about how steam cars operate

- The Steam Automobile Club of America

- Stanley Register Online, a worldwide register of existing Stanley steam cars.

- The British Steam Car Challenge (an ongoing project started in 1999 dedicated to breaking the land speed record for a steam-powered vehicle).

- Overview on an attempt to break the existing 101-year-old Steam car world land speed record

- One day Steam Car conversion, where two teams in the UK TV series Scrapheap Challenge (Junkyard Wars in the US) converted junk cars into coal-fired steam cars.

- Steam 101