Aneurysm

| Aneurysm | |

|---|---|

| aneurism | |

|

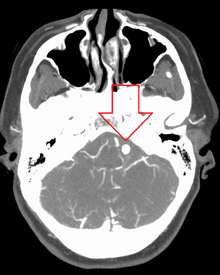

Angiography of an aneurysm in a cerebral artery. The aneurysm is the bean-shaped gray blob in the center of the image. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Vascular surgery |

| ICD-10 | I72 |

| ICD-9-CM | 442 |

| DiseasesDB | 15088 |

| MedlinePlus | 001122 |

| MeSH | D000783 |

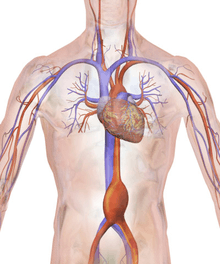

An aneurysm is a localized, blood-filled balloon-like bulge in the wall of a blood vessel.[1] Aneurysms can occur in any blood vessel, with examples including aneurysms of the Circle of Willis in the brain, aortic aneurysms affecting the thoracic aorta, and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aneurysms can also occur within the heart.

As an aneurysm increases in size, the risk of rupture increases.[2] A ruptured aneurysm can lead to bleeding. Aneurysms are a result of a weakened blood vessel wall, and can be a result of a hereditary condition or an acquired disease. Aneurysms can also be a nidus for clot formation (thrombosis) and embolization. The word is from Greek: ἀνεύρυσμα, aneurysma, "dilation", from ἀνευρύνειν, aneurynein, "to dilate".

Classification

Aneurysms may be classified by type, morphology, or location.

True and false aneurysms

A true aneurysm is one that involves all three layers of the wall of an artery (intima, media and adventitia). True aneurysms include atherosclerotic, syphilitic, and congenital aneurysms, as well as ventricular aneurysms that follow transmural myocardial infarctions (aneurysms that involve all layers of the attenuated wall of the heart are also considered true aneurysms).[3]

A false aneurysm, or pseudoaneurysm, is a collection of blood leaking completely out of an artery or vein, but confined next to the vessel by the surrounding tissue. This blood-filled cavity will eventually form either thrombose (clot) enough to seal the leak, or rupture out of the surrounding tissue.[3]:357

Pseudoaneurysms can be caused by trauma that punctures the artery, such as knife and bullet wounds,[4] as a result of percutaneous surgical procedures such as coronary angiography or arterial grafting,[5] or use of an artery for injection.[6]

Morphology

Aneurysms can also be classified by their macroscopic shape and size, and are described as either saccular or fusiform. The shape of an aneurysm is not specific for a specific disease.[3]:357

Saccular aneurysms are spherical in shape and involve only a portion of the vessel wall; they vary in size from 5 to 20 cm (8 in) in diameter, and are often filled, either partially or fully, by a thrombus.[3]:357

Fusiform aneurysms ("spindle-shaped" aneurysms) are variable in both their diameter and length; their diameters can extend up to 20 cm (8 in). They often involve large portions of the ascending and transverse aortic arch, the abdominal aorta, or less frequently the iliac arteries.[3]:357

Location

Aneurysms can also be classified by their location:

- Arterial and venous, with arterial being more common.

- The heart, including coronary artery aneurysms, ventricular aneurysms, aneurysm of sinus of Valsalva, and aneurysms following cardiac surgery.

- The aorta, namely aortic aneurysms including thoracic aortic aneurysms and abdominal aortic aneurysms.

- The brain, including cerebral aneurysms, berry aneurysms, and Charcot–Bouchard aneurysms.

- The legs, including the popliteal arteries.

- The kidney, including renal artery aneurysm and intraparechymal aneurysms.[7]

- Capillaries, specifically capillary aneurysms.

Cerebral aneurysms, also known as intracranial or brain aneurysms, occur most commonly in the anterior cerebral artery, which is part of the circle of Willis. This can cause severe strokes leading to death. The next most common sites of cerebral aneurysm occurrence are in the internal carotid artery.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Aneurysm presentation may range from life-threatening complications of hypovolemic shock to being found incidentally on X-ray.[9] Symptoms will differ by the site of the aneurysm and can include:

Cerebral aneurysm

Symptoms can occur when the aneurysm pushes on a structure in the brain. Symptoms will depend on whether an aneurysm has ruptured or not. There may be no symptoms present at all until the aneurysm ruptures.[10] For an aneurysm that has not ruptured the following symptoms can occur:

- Fatigue

- Loss of perception

- Loss of balance

- Speech problems

- Double vision

For a ruptured aneurysm, symptoms of a subarachnoid hemorrhage may present:

- Severe headaches

- Loss of vision

- Double vision

- Neck pain and/or stiffness

- Pain above and/or behind the eyes

Abdominal aneurysm

Abdominal aneurysms are usually asymptomatic, but rarely can cause lower back pain or lower limb ischemia

Renal (kidney) aneurysm

- Flank pain and tenderness

- Hypertension

- Haematuria

- Signs of hypovolemic shock

Risk factors

Risk factors for an aneurysm include diabetes, obesity, hypertension, tobacco use, alcoholism, high cholesterol, copper deficiency, increasing age, and tertiary syphilis infection.[9]:602

Specific infective causes associated with aneurysm include:

- Advanced syphilis infection resulting in syphilitic aortitis and an aortic aneurysm

- Tuberculosis, causing Rasmussen's aneurysms

- Brain infections, causing infectious intracranial aneurysms

A minority of aneurysms are associated with genetic factors. Examples include:

- Berry aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery of the circle of Willis, associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease[11]

- Familial thoracic aortic aneurysms

- Cirsoid aneurysms, secondary to congenital arteriovenous malformations

Pathophysiology

Aneurysms form for a variety of interacting reasons. Multiple factors, including factors affecting a blood vessel wall and the blood through the vessel, contribute.

Atherosclerosis. A variety of different factors, including atherosclerosis, may contribute to weakening of a blood vessel wall. The repeated trauma of blood flowing through the vessel may contribute to degeneration of the vessel wall. Hypertensive injury may compound this degeneration and accelerate the expansion of the aneurysm. As the aneurysm expands, the wall tension increases.[12]

The pressure of blood within the expanding aneurysm may also injure the blood vessels supplying the artery itself, further weakening the vessel wall. Without treatment, these aneurysms will ultimately progress and rupture.[13]

Infection. A mycotic aneurysm is an aneurysm that results from an infectious process that involves the arterial wall.[14] A person with a mycotic aneurysm has a bacterial infection in the wall of an artery, resulting in the formation of an aneurysm. The most common locations include arteries in the abdomen, thigh, neck, and arm. A mycotic aneurysm can result in sepsis, or life-threatening bleeding if the aneurysm ruptures. Less than 3% of abdominal aortic aneurysms are mycotic aneurysms.[15]

Syphilis. The third stage of syphilis also manifests as aneurysm of the aorta, which is due to loss of the vasa vasorum in the tunica adventitia.[16]

Copper Deficiency. A minority of aneurysms are caused by copper deficiency, which results in a decreased activity of the lysyl oxidase enzyme, affecting elastin, a key component in vessel walls[17][18][19] Copper deficiency results in vessel wall thinning,[20] and thus has been noted as a cause of death in copper-deficient humans,[21] chickens and turkeys[22]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm is commonly made by finding signs of subarachnoid hemorrhage on a computed tomography (CT) scan. If the CT scan is negative but a ruptured aneurysm is still suspected based on clinical findings, a lumbar puncture can be performed to detect blood in the cerebrospinal fluid. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is an alternative to traditional angiography and can be performed without the need for arterial catheterization. This test combines a regular CT scan with a contrast dye injected into a vein. Once the dye is injected into a vein, it travels to the cerebral arteries, and images are created using a CT scan. These images show exactly how blood flows into the brain arteries.

Treatment

Historically, the treatment of arterial aneurysms has been limited to either surgical intervention, or watchful waiting in combination with control of blood pressure. In recent years, endovascular or minimally invasive techniques have been developed for many types of aneurysms. Aneurysm Clips are used for surgical procedure i.e. clipping of aneurysms.[23]

Intracranial aneurysms

There are currently two treatment options for brain aneurysms: surgical clipping or endovascular coiling. There is currently debate in the medical literature about which treatment is most appropriate given particular situations.

Surgical clipping was introduced by Walter Dandy of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1937. It consists of a craniotomy to expose the aneurysm and closing the base or neck of the aneurysm with a clip. The surgical technique has been modified and improved over the years.

Endovascular coiling was introduced by Guido Guglielmi at UCLA in 1991. It consists of passing a catheter into the femoral artery in the groin, through the aorta, into the brain arteries, and finally into the aneurysm itself. Platinum coils initiate a clotting reaction within the aneurysm that, if successful fill the aneurysm dome and prevent its rupture.

Aortic and peripheral aneurysms

For aneurysms in the aorta, arms, legs, or head, the weakened section of the vessel may be replaced by a bypass graft that is sutured at the vascular stumps. Instead of sewing, the graft tube ends, made rigid and expandable by nitinol wireframe, can be easily inserted in its reduced diameter into the vascular stumps and then expanded up to the most appropriate diameter and permanently fixed there by external ligature.[24][25] New devices were recently developed to substitute the external ligature by expandable ring allowing use in acute ascending aorta dissection, providing airtight (i.e. not dependent on the coagulation integrity), easy and quick anastomosis extended to the arch concavity[26][27][28] Less invasive endovascular techniques allow covered metallic stent grafts to be inserted through the arteries of the leg and deployed across the aneurysm.

Renal aneurysms

Renal aneurysms are very rare consisting of only 0.1–0.09%[29] while rupture is even more rare.[29][30] Conservative treatment with control of concomitant hypertension being the primary option with aneurysms smaller than 3 cm. If symptoms occur, or enlargement of the aneurysm, then endovascular or open repair should be considered.[31] Pregnant women due to high rupture risk of up to 80% should be treated surgically.[32]

Epidemiology

Incidence rates of cranial aneurysms are estimated at between 0.4% and 3.6%. Those without risk factors have expected prevalence of 2–3%.[8]:181 In adults, females are more likely to have aneurysms. They are most prevalent in people ages 35 – 60, but can occur in children as well. Aneurysms are rare in children with a reported prevalence of .5% to 4.6%. The most common incidence are among 50-year-olds, and there are typically no warning signs. Most aneurysms develop after the age of 40.

Pediatric aneurysms

Pediatric aneurysms have different incidences and features than adult aneurysms.[33] Intracranial aneurysms are rare in childhood, with over 95% of all aneurysms occurring in adults.[8]:235

Risk factors

Incidence rates are two to three times higher in males, while there are more large and giant aneurysms and fewer multiple aneurysms.[8]:235 Intracranial hemorrhages are 1.6 times more likely to be due to aneurysms than cerebral arteriovenous malformations in whites, but four times less in certain Asian populations.[8]:235

Most patients, particularly infants, present with subarachnoid hemorrhage and corresponding headaches or neurological deficits. The mortality rate for pediatric aneurysms is lower than in adults.[8]:235

Notable cases

- Lucille Ball, who died from an aortic rupture in the abdominal area days after having undergone apparently successful heart surgery for a dissecting aortic aneurysm[34][35][36][37]

- Laura Branigan, who died of a cerebral aneurysm

- David Cone, who suffered from an aneurysm and missed most of the 1996 baseball season

- Albert Einstein, who died from a repaired aortic aneurysm[38]

- Charles de Gaulle, who died from an aneurysm within his neck

- Richard Holbrooke, who died from a thoracic aortic aneurysm[39]

- Stuart Sutcliffe, who died from an aneurysm in his brain's right hemisphere[40]

References

- ↑ "Aneurysm" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Cronenwett, JL; Murphy, TF; Zelenock, GB; Whitehouse WM, Jr; Lindenauer, SM; Graham, LM; Quint, LE; Silver, TM; Stanley, JC (September 1985). "Actuarial analysis of variables associated with rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms". Surgery. 98 (3): 472–83. PMID 3898453.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kumar, Vinay, ed. (2007). Robbins basic pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ↑ Baird, RJ; Doran, ML (August 8, 1964). "The False Aneurysm". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 91: 281–4. PMC 1927240

. PMID 14180533.

. PMID 14180533. - ↑ Norwood, M.G.A.; Lloyd, G.M.; Moore, S.; Patel, N.; Panditi, S.; Sayers, R.D. (2004). "The Changing Face of Femoral Artery False Aneurysms". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 27 (4): 385–388. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.01.001. PMID 15015188.

- ↑ Li, JW; Wang, SM; Chen, XD (August 2004). "Management of femoral artery pseudoaneurysm due to addictive drug injection". Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 7 (4): 244–6. PMID 15294105.

- ↑ "A Cough Deteriorating Gross Hematuria: A Clinical Sign of a Forthcoming Life-Threatening Rupture of an Intraparenchymal Aneurysm of Renal Artery (Wunderlich's Syndrome)". Case Reports in Vascular Medicine. 2013: 1–3. doi:10.1155/2013/452317.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Christianto B. Lumenta, ed. (2010). Neurosurgery. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 181. ISBN 3-540-79564-2.

- 1 2 Britton, the editors Nicki R. Colledge, Brian R. Walker, Stuart H. Ralston ; illustrated by Robert (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 604. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ↑ Manasco, Hunter. "The Aphasias". Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. p. 93.

- ↑ Stephen J. Schueler, MD; John H. Beckett, MD; D. Scott Gettings, MD (August 18, 2010). "Berry Aneurysm in the Brain". freemd. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ as described by the Law of Laplace

- ↑ Juvela, Seppo; Porras, Matti; Poussa, Kristiina (1 May 2008). "Natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: probability of and risk factors for aneurysm rupture". Journal of Neurosurgery. 108 (5): 1052–1060. doi:10.3171/JNS/2008/108/5/1052. PMID 18447733.

- ↑ emedicine – Cerebral Aneurysm Author: Jonathan L Brisman. Coauthors: Emad Soliman, Abraham Kader, Norvin Perez. Updated: Sep 23, 2010

- ↑ Author: Stephen J. Schueler, MD; Coauthors: John H. Beckett, MD; D. Scott Gettings, MD. Updated November 13, 2011

- ↑ Paulo, N.; Cascarejo, J.; Vouga, L. (28 November 2011). "Syphilitic aneurysm of the ascending aorta". Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery. 14 (2): 223–225. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivr067. PMC 3279976

. PMID 22159251.

. PMID 22159251. - ↑ Mäki, Joni (2002). Lysyl oxidases : cloning and characterization of the fourth and the fifth human lysyl oxidase isoenzymes, and the consequences of a targeted inactivaton of the first described lysyl oxidase isoenzyme in mice (PDF). Oulu: Oulun yliopisto. ISBN 951-42-6739-7.

- ↑ Rucker, RB; Kosonen, T; Clegg, MS; Mitchell, AE; Rucker, BR; Uriu-Hare, JY; Keen, CL (May 1998). "Copper, lysyl oxidase, and extracellular matrix protein cross-linking.". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 67 (5 Suppl): 996S–1002S. PMID 9587142.

- ↑ Smith-Mungo, LI; Kagan, HM (February 1998). "Lysyl oxidase: properties, regulation and multiple functions in biology.". Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 16 (7): 387–98. doi:10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90012-9. PMID 9524359.

- ↑ Senapati, A; Carlsson, LK; Fletcher, CD; Browse, NL; Thompson, RP (May 1985). "Is tissue copper deficiency associated with aortic aneurysms?". The British journal of surgery. 72 (5): 352–3. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800720507. PMID 3995240.

- ↑ Tilson, MD (September 1982). "Decreased hepatic copper levels. A possible chemical marker for the pathogenesis of aortic aneurysms in man.". Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 117 (9): 1212–3. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380330070017. PMID 7202350.

- ↑ Guenthner, E; Carlson, CW; Emerick, RJ (September 1978). "Copper salts for growth stimulation and alleviation of aortic rupture losses in turkeys.". Poultry science. 57 (5): 1313–24. doi:10.3382/ps.0571313. PMID 724600.

- ↑ http://surgicalunits.com/aneurysm-clip-311.html

- ↑ "sp.html". Fondazionecarrel.org. doi:10.1510/icvts.2009.216291. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ Aluffi A, Berti A, Buniva P, Rescigno G, Nazari S (2002). "Improved device for sutureless aortic anastomosis applied in a case of cancer". Tex Heart Inst J. 29 (1): 56–9. PMC 101273

. PMID 11995854.

. PMID 11995854. - ↑ Nazari Stefano (2010). "Expandable device type III for easy and reliable approximation of dissection layers in sutureless aortic anastomosis. Ex vivo experimental study". Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 10: 161–164. doi:10.1510/icvts.2009.216291. PMID 19933306.

- ↑ Stefano Nazari. "Expandable device type III for easy and reliable approximation of dissection layers in sutureless aortic anastomosis. Ex vivo experimental study". Icvts.ctsnetjournals.org. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ "ndicvts.html". Fondazionecarrel.org. doi:10.1510/icvts.2009.216291. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- 1 2 Schorn B, Falk V, Dalichau H, et al. (1997). "Kidney salvage in a case of ruptured renal artery aneurysm: case report and literature review". Cardiovasc Surg. 5 (1): 134–136. doi:10.1016/s0967-2109(95)00041-0.

- ↑ Tham G, Ekelund L, Herrlin K (1983). "Renal artery aneurysms. Natural history and prognosis". Ann Surg. 197 (3): 348–352. doi:10.1097/00000658-198303000-00016. PMID 6830341.

- ↑ Uflacker R. Interventional management of visceral artery aneurysms. In: Strandness DE, ed. Vascular Diseases: Surgical & Interventional Therapy. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:823–844.

- ↑ Lumsden AB, Salam TA, Walton KG (1996). "Renal artery an?eurysm: a report of 28 cases". Cardiovasc Surg. 4 (2): 185–189.

- ↑ "Brain Aneurysm Basics | The Brain Aneurysm Foundation". Bafound.org. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ "The Death of Lucille Ball". findadeath.com. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ↑ Ball, Lucille (April 27, 1989). "Lucy dies". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Article: Lucille Ball, Pioneer of Television Comedy, Dies at 77". Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ↑ Ball, Lucille (April 27, 1989). "Ball dies of ruptured aorta". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0314.html

- ↑ http://www.nbcnews.com/id/40649624/ns/politics/t/us-diplomat-holbrooke-dies-after-tearing-aorta/

- ↑ http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/stuart-sutcliffe-legacy-fifth-beatle-3346849

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aneurysms. |

| Look up aneurysm in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Berry Aneurysm overview

- @neurIST – Integrated Biomedical Informatics for the Management of Cerebral Aneurysms

- Brain aneurysm and percent packing calculator