Archaeology of Israel

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Israel |

|

| Ancient Israel and Judah |

| Second Temple period (530 BCE–70 CE) |

| Middle Ages (70–1517) |

| Modern history (1517–1948) |

| State of Israel (1948–present) |

| History of the Land of Israel by topic |

| Related |

|

|

The archaeology of Israel is the study of the archaeology of the present-day Israel, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. The ancient Land of Israel was a geographical bridge between the political and cultural centers of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Despite the importance of the country to three major religions, serious archaeological research only began in the 15th century.[1] The first major work on the antiquities of Israel was Adrian Reland's Palestina ex monumentis veteribus, published in 1709. Edward Robinson, an American theologian who visited the country in 1838, published the first topographical studies. A Frenchman, Louis Felicien de Saucy, embarked on the first "modern" excavations in 1850.[1]

In discussing the state of archaeology in Israel in his time, David Ussishkin commented in the 1980s that the designation "Israeli archeology" no longer represents a single uniform methodological approach; rather, its scope covers numerous different archaeological schools, disciplines, concepts, and methods currently in existence in Israel.[2]

Archaeological time periods

Neolithic period

The Neolithic period appears to have begun when the peoples of the Natufian culture, which spread across present-day Syria, Israel and Lebanon, began to practice agriculture. This Neolithic Revolution has been linked to the cold period known as the Younger Dryas. This agriculture in the Levant is the earliest known to have been practiced. The Neolithic period in this region is dated 8500–4300 BCE and the Chalcolithic 4300–3300 BCE. The term "Natufian" was coined by Dorothy Garrod in 1928, after identifying an archaeological sequence at Wadi al-Natuf which included a Late Levallois-Mousterian layer and a stratified deposit, the Mesolithic of Palestine, which contained charcoal traces and a microlithic flint tool industry.[3] Natufian sites in Israel include Ain Mallaha, el-Wad, Ein Gev, Hayonim cave, Nahal Oren and Kfar HaHoresh.

Bronze Age / Canaanite period

The Bronze Age is the period 3300–1200 BCE when objects made of bronze were in use. Many writers have linked the history of the Levant from the Bronze Age onwards to events described in the Bible. The Bronze Age and Iron Age together are sometimes called the "Biblical period".[4] The periods of the Bronze Age include the following:

- Early Bronze Age I (EB I) 3330–3050 BCE

- Early Bronze Age II–III (EB II–III) 3050–2300 BCE

- Early Bronze Age IV/Middle Bronze Age I (EB IV/MB I) 2300–2000 BCE

- Middle Bronze Age IIA (MB IIA) 2000–1750 BCE

- Middle Bronze Age IIB (MB IIB) 1800–1550 BCE

- Late Bronze Age I–II (LB I–II) 1550–1200 BCE

The Late Bronze Age is characterized by individual city-states, which from time to time were dominated by Egypt until the last invasion by Merenptah in 1207 BCE. The Amarna Letters are an example of a specific period during the Late Bronze Age when the vassal kings of the Levant corresponded with their overlords in Egypt.

Iron Age/Israelite period

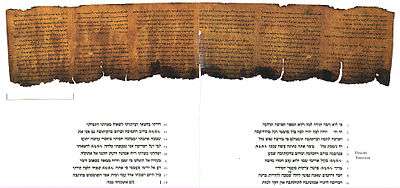

The Iron Age in the Levant begins in about 1200 BCE when iron tools came into use. It is also known as the Israelite period. The Israelite period is characterized by large numbers of urban dwellings and a new local culture. The rich and diverse archaeological findings attest to strong international links and trade relations. The abundance of writings found indicate a broad distribution of knowledge among common people of ancient Israel and not just scribes, a unique phenomenon in the ancient world.

In this period both the archaeological evidence and the narrative evidence from the Bible become richer and much writing has attempted to make links between them. A chronology includes:

- Iron Age I (IA I) 1200–1000 BCE

- Iron Age IIA (IA IIA) 1000–925 BCE

- Iron Age IIB-C (IA IIB-C) 925–586 BCE

- Iron Age III 586–539 BCE (Neo-Babylonian period)

The traditional view, personified in such archaeologists as Albright and Wright, faithfully accepted the biblical events as history, but has since been questioned by "Biblical minimalists" such as Niels Peter Lemche, Thomas L. Thompson and Philip R. Davies. Israel Finkelstein[5] suggests that the empire of David and Solomon (United Monarchy) never existed and Judah was not in a position to support an extended state until the start of the 8th century. Finklestein accepts the existence of King David and Solomon but doubts their chronology, significance and influence as described in the Bible.[6] Without claiming that everything in the Bible is historically accurate, some non-supernatural story elements appear to correspond with physical artifacts and other archaeological findings. Inscriptions such as the Tel Dan Stele and the Mesha Stele can be traced to a non-Hebrew cultural origin.

Persian period

Hellenistic period

Roman period

The Roman period covers the dates 63 BCE to 330 CE, from Pompey the Great's incorporation of the region into the Roman Republic until Rome's adoption of Christianity as the imperial religion. The Roman period itself features several stages:

- Early Roman period (including the Herodian period) 63 BCE to 70 CE

- Middle Roman period: 70–135 CE (Jewish-Roman wars period); 135–200 CE (Mishnaic period)

- Late Roman period 200–330 CE (Talmudic period)

The end of the middle Roman period marks the end of the predominantly Jewish culture of Judea, but also the beginning of Rabbinic Judaism through Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakai in the city of Yavne. Therefore, the late Roman period is also called the Yavne Period.

Prominent archaeological sites from the Roman period include:

Byzantine period

The Byzantine period is dated 330–638 CE, from Rome's adoption of Christianity to the Muslim conquest of Palestine.

Findings from the Byzantine period include:

- Byzantine-period church in Jerusalem hills[9][10]

- Byzantine-period street in Jerusalem[11]

- 1,400-year-old wine press[12]

Notable sites

Ashkelon

Archaeological excavation in Ashkelon began in 1985, led by Lawrence Stager[13] The site contains 50 feet (15 m) of accumulated rubble from successive Canaanite, Philistine, Phoenician, Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Islamic, and Crusader occupation. Major findings include shaft graves of pre-Phoenician Canaanites, a Bronze Age vault and ramparts, and a silvered bronze statuette of a bull calf, assumed to be of the Canaanite period.[14]

Beit Alfa

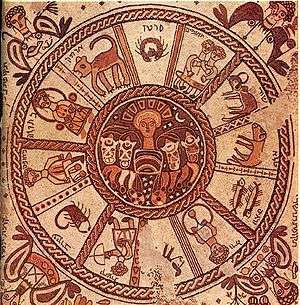

One of the earliest digs by Israeli archaeologists, Beit Alfa is the site of an ancient Byzantine-era synagogue, constructed in the 5th century CE, with a three-paneled mosaic floor. An Aramaic inscription states that the mosaic was made at the time of Justin (apparently Justin I), who ruled from 518 to 527 CE. The mosaic is one of the most important discovered in Israel. Each of its three panels depicts a scene—the Holy Ark, the zodiac, and the story of the sacrifice of Isaac. The zodiac has the names of the twelve signs in Hebrew. In the center is Helios, the sun god, being whisked away in his chariot by four galloping horses. The four women in the corners of the mosaic represent the four seasons.[15]

Carmel Caves

Misliya Cave, southwest of Mt. Carmel, has been excavated by teams of anthropologists and archaeologists from the Archaeology Department of the University of Haifa and Tel Aviv University since 2001. In 2007, they unearthed artifacts indicative of what could be the earliest known prehistoric man. The teams uncovered hand-held stone tools and blades as well as animal bones, dating to 250,000 years ago, at the time of the Mousterian culture of Neanderthals in Europe.[16]

Mamshit

Mamshit, the Nabatean city of Memphis (also known as Kurnub in Arabic), was declared a world heritage site by UNESCO on June 2005. The archaeological excavation at Mamshit uncovered the largest hoard of coins ever found in Israel: 10,500 silver coins in a bronze jar, dating to the 3rd century CE.[17] Among the Nabatean cities found in the Negev (Avdat, Haluza, Shivta) Mamshit is the smallest (10 acres), but the best preserved and restored. Entire streets have survived intact, and numerous Nabatean buildings with open rooms, courtyards, and terraces have been restored. Most of the buildings were built in the late Nabatean period, in the 2nd century CE, after the Nabatean kingdom was annexed to Rome in 106 CE.

Old Acre

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001,[18] Acre's Old City has been the site of extensive archaeological excavation since the 1990s. The major find has been an underground passageway leading to a 13th-century fortress of the Knights Templar. The excavated remains of the Crusader town, dating from 1104 to 1291 CE, are well preserved, and are on display above and below the current street level.

Tel Rehov

Tel Rehov is an important Bronze and Iron Age archaeological site approximately five kilometers south of Beit She'an and three kilometers west of the Jordan River. The site represents one of the largest ancient city mounds in Israel, its surface area comprising 120,000 m² in size, divided into an "Upper City" (40,000 m²) and a "Lower City" (80,000 m²). Archaeological excavations have been conducted at Rehov since 1997, under the directorship of Amihai Mazar. The first eight seasons of excavations revealed successive occupational layers from the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I (12th - 11th centuries BCE).[19] The Iron Age II levels of the site have emerged as a vitally important component in the current debate regarding the chronology of the United Monarchy of Israel.[20] In September 2007, 30 intact beehives dated to the mid-10th to early 9th century BCE were found.[21] The beehives are evidence of an advanced honey-producing beekeeping (apiculture) industry 3,000 years ago in the city, then thought to have a population of about 2,000. The beehives, made of straw and unbaked clay, were found in orderly rows of 100 hives. Organic material (wheat found next to the beehives) was dated using carbon-14 radiocarbon dating at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. Also found alongside the hives was an altar decorated with fertility figurines.[22]

Tel Be'er Sheva

A UNESCO World Heritage site since 2005, Tel Be'er Sheva is an archaeological site in southern Israel, believed to be the remains of the biblical town of Be'er Sheva. Archaeological finds indicate that the site was inhabited from the Chalcolithic period, around 4000 BCE,[23][24] to the 16th century CE. This was probably due to the abundance of underground water, as evidenced by the numerous wells in the area. Excavated by Yohanan Aharoni and Ze'ev Herzog of Tel Aviv University, the settlement itself is dated to the early Israelite period.[25] Probably populated in the 12th century BCE, the first fortified settlement dates to 1000 BCE.[26] The city was likely destroyed by Sennacherib in 700 BCE, and after a habitation hiatus of three hundred years, there is evidence of remains from the Persian, Hellenistic, Roman and Early Arab periods.[26] Major finds include an elaborate water system and a huge cistern[27] carved out of the rock beneath the town, and a large horned altar which was reconstructed using several well-dressed stones found in secondary use in the walls of a later building. The altar attests to the existence of a temple or cult center in the city which was probably dismantled during the reforms of King Hezekiah.[28]

Tel Megiddo

A UNESCO World Heritage site since 2005, Tel Megiddo comprises twenty-six stratified layers of the ruins of ancient cities in a strategic location at the head of a pass through the Carmel Ridge, which overlooks the Valley of Jezreel from the west. Megiddo has been excavated three times. The first excavations were carried out between 1903 and 1905 and a second expedition was carried out in 1925. During these excavation it was discovered that there were twenty levels of habitation, and many of the remains uncovered are preserved at the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Yigael Yadin conducted a few small excavations in the 1960s. Since 1994, Megiddo been the subject of biannual excavation campaigns conducted by The Megiddo Expedition of Tel Aviv University, directed by Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, together with a consortium of international universities. A major find from digs conducted between 1927 and 1934 were the Megiddo Stables – two tripartite structures measuring 21 meters by 11 meters, believed to have been ancient stables capable of housing nearly 500 horses.

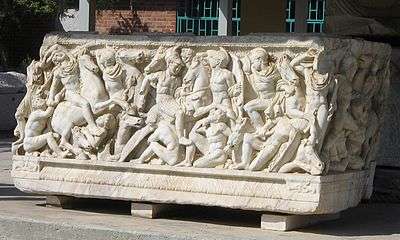

Beit She'arim

Beit She'arim is an archaeological site of a Jewish town and necropolis, near the town of Kiryat Tiv'on, 20 km east of Haifa in the southern foothills of the Lower Galilee. Beth She'arim was excavated by Benjamin Mazar[29] and Nahman Avigad in the 1930s and 1950s. Most of the remains date from the 2nd to 4th century CE and include the remains of a large number of individuals buried in the more than twenty catacombs of the necropolis. Together with the images on walls and sarcophagi, the inscriptions show that this was a Jewish necropolis.[30]

Gath

Tell es-Safi/Gath is one of the largest pre-Classical sites in Israel, situated approximately halfway between Jerusalem and Ashkelon, on the border between coastal plain and the Judean foothills (Shephelah). The site was settled from Prehistoric to Modern times, and was of particular importance during the Bronze and Iron Ages, and during the Crusader period. The site is identified as Canaanite and Philistine Gath, and during the Iron Age was one of the five main cities (the Pentapolis) of the Philistines. The site was excavated briefly in 1899 by the British archaeologists Frederick Jones Bliss and Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, and since 1996, by a team from Bar-Ilan University directed by Aren Maeir.[31] Among the noteworthy finds from the ongoing excavations are the impressive late 9th-century BCE destruction level (Stratum A3), apparently evidence of the destruction of Gath by Hazael of Aram (see II Kings 12:18), a unique siege system relating to this event that surrounds the site (the earliest known siege system in the world), a 10th/9th-century BCE inscription written in archaic alphabetic script, mentioning two names of Indo-European nature, somewhat reminiscent of the etymological origins of the name Goliath, and a large stone altar with two "horns" from the 9th-century BCE destruction level - which while very similar to the biblical description of the altar in the Tabernacle (in Exodus 30), has only two horns (as opposed to four in other known examples), perhaps indicating a unique type of Philistine altar, perhaps influenced from Cypriot, and perhaps Minoan, culture.

Gezer

Tel Gezer is an archaeological site which sits on the western flank of the Shephelah, overlooking the coastal plain of Israel, near the junction between Via Maris and the trunk road leading to Jerusalem. The tel consists of two mounds with a saddle between them, spanning roughly 30 acres (120,000 m2). A dozen inscribed boundary stones found in the vicinity verify the identification of the mound as Gezer, making it the first positively identified Biblical city. Gezer is mentioned in several ancient sources, including the Hebrew Bible and the Amarna letters. The biblical references describe it as one of Solomon's royal store cities.[32] R.A.S. Macalister excavated Gezer from 1902 to 1909 with a one-year hiatus in 1906. Major findings include a soft limestone tablet, named the Gezer calendar, which describes the agricultural chores associated with each month of the year. The calendar is written in paleo-Hebrew script, and is one of the oldest known examples of Hebrew writing, dating to the 10th century BCE. Also found was a six-chambered gate similar to those found at Hazor and Megiddo, and ten monumental megaliths.

Masada

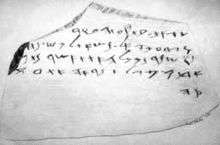

A UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2001, Masada is the site of ancient palaces and fortifications in the Southern District (Israel) on top of an isolated rock plateau, or large mesa, on the eastern edge of the Judean Desert overlooking the Dead Sea. According to Josephus, a 1st-century Jewish-Roman historian, Herod the Great fortified Masada between 37 and 31 BCE as a refuge for himself in the event of a revolt. Josephus also writes that in 66 CE, at the beginning of the First Jewish-Roman War against the Roman Empire, a group of Judaic extremist rebels called the Sicarii took Masada from the Roman garrison stationed there.[33] The site of Masada was identified in 1842 and extensively excavated between 1963 and 1965 by an expedition led by Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin. Due to the remoteness from human habitation and the arid environment, the site has remained largely untouched by humans or nature during the past two millennia. Many of the ancient buildings have been restored, as have the wall-paintings of Herod's two main palaces, and the Roman-style bathhouses that he built. A synagogue thought to have been used by the Jewish rebels has also been identified and restored.[34] Inside the synagogue, an ostracon bearing the inscription me'aser kohen ("tithe for the priest") was found, as were fragments of two scrolls.[35] Also found were eleven small ostraca, each bearing a single name. One reads "ben Yair" and could be short for Eleazar ben Yair, the commander of the fortress.[36] Excavations also uncovered the remains of 28 skeletons.[33] Carbon dating of textiles found in the cave indicate they are contemporaneous with the period of the Revolt.[37] The remnants of a Byzantine church dating from the 5th and 6th centuries CE, have also been excavated on the top of Masada.

Tel Arad

Tel Arad is located west of the Dead Sea, about ten kilometers west of modern Arad. Excavations at the site conducted by Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni in 1962[38] have unearthed an extensive early Bronze Age settlement that was completely deserted and destroyed by 2700 BCE.[39] The site was then apparently deserted until a new settlement was founded on the southeastern ridge of the ancient city during the Iron Age II.[39] The major find was a garrison-town known as 'The Citadel', constructed in the time of King David and Solomon.[40] A Judean temple, the earliest ever to be discovered in an excavation, dates back to the mid-10th century BCE.[39] An inscription found on the site by Aharoni mentions a 'House of YHWH', which William G. Dever suggests may have referred to the temple at Arad or the temple at Jerusalem.[41][42] The Arad temple was probably demolished around 700 CE, which is before the date of the inscription.[43]

Tel Dan

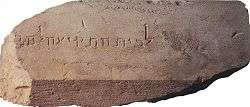

Tel Dan, previously named Tell el-Qadi, is a mound where a city once stood, located at the northern tip of modern-day Israel. Finds at the site date back to the Neolithic era circa 4500 BCE, and include 0.8 meter wide walls and pottery shards. The most important find is the Tel Dan Stele, a black basalt stele, whose fragments were discovered in 1993 and 1994. The stele was erected by an Aramaean king and contains an Aramaic inscription to commemorate his victory over the ancient Hebrews. It has generated much excitement because the inscription includes the letters 'ביתדוד', Hebrew for "house of David".[44] Proponents of that reading argue that it is the first time that the name "David" has been recognized at any archaeological site, lending evidence for the Bible account of David's kingdom. Others read the Hebrew letters 'דוד' as "beloved," "uncle" "kettle," or "a god named Dod," (all of which are possible readings of vowel-less Hebrew), and argue this is not a reference to Biblical David.[44]

Tel Hazor

A UNESCO World Heritage site since 2005, Tel Hazor has been excavated repeatedly since 1955. Other findings include an ancient Canaanite city, which experienced a catastrophic fire in the sometime in the 13th century BCE. The date and causes of the violent destruction of Canaanite Hazor have been an important issue ever since the first excavations of the site. One school of thought, represented by Yigael Yadin, Yohanan Aharoni and Amnon Ben-Tor, dates the destruction to the later half of the 13th century, tying it to biblical descriptions in Joshua which hold the Israelites responsible for the event. The second school of thought, represented by Olga Tufnell, Kathleen Kenyon, P. Beck, Moshe Kochavi and Israel Finkelstein, tends to support an earlier date in the first half of the 13th century, in which case there is no necessary connection between the destruction of Hazor and the process of settlement by Israelite Tribes in Cannan.[45] Other findings at the site include a distinctive six chambered gate dating to the Early Iron Age, as well as pottery and administrative buildings dating to either the 10th century and King Solomon or, on a lowered chronology, to the Omrides of the 9th century.

Tzippori

Excavations in Tzippori, in the central Galilee region, six kilometers north-northwest of Nazareth, have uncovered a rich and diverse historical and architectural legacy that includes Assyrian, Hellenistic, Judean, Babylonian, Roman, Byzantine, Islamic, Crusader, Arabic and Ottoman influences. The site is especially rich in mosaics belonging to different periods. Major findings include the remains of a 6th-century synagogue, evidence of an interesting fusion of Jewish and pagan beliefs. A Roman villa, considered the centerpiece of the discoveries, which dates to the year 200 CE, was destroyed in the Galilee earthquake of 363 CE. The mosaic floor was discovered in August 1987 during an expedition led by Eric and Carol Meyers, of Duke University digging with Ehud Netzer, a locally trained archaeologist from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[46] It depicts Dionysus, the god of wine, socializing with Pan and Hercules in several of the 15 panels. In its center is a lifelike image of a young lady, possibly Venus, which has been named "The Mona Lisa of the Galilee." Additional finds include a Roman theater on the northern slope of the hill, and the remains of a 5th-century public building, with a large and intricate mosaic floor. [47]

Gesher Bnot Ya'akov

Bnot Ya'akov Bridge is a 780,000-year-old site on the banks of the Jordan river in northern Israel currently excavated by Naama Goren-Inbar of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. First discovered in the 1930s, Bnot Ya'akov had been the site of several excavations that provided archaeologists with crucial information about how and when Homo erectus moved out of Africa, most likely through the Levantine corridor that includes Israel. "One of the rarest prehistoric sites in the world," it featured a remarkable level of organic preservation that archaeologists had not encountered at any other contemporary site in Europe or Asia. In 2000, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) charged the Sea of Galilee Drainage Authority (KDA) with causing "serious and irreversible damage" to the site. While the KDA had procured permission from the IAA to work in a limited area to alleviate the regular flooding of farmland in the adjacent Hula Valley under the supervision of an IAA inspector, bulldozers entered the site at night, damaging fossil remains, manmade stone artifacts, and organic material.[48]

Ain Mallaha

Ain Mallaha, a Natufian village, colonized in three phases 12,000 to 9600 BCE, contains the earliest known archaeological evidence of dog domestication: the burial of a human being with a dog.[49]

Archaeological institutions

During the last hundred years of Ottoman rule in Palestine, Western archaeologists active in the region tended to be Christian, backed by the dominant European powers of the time and the Churches. With the transition from Ottoman to British rule over the land, the pursuit of archaeology became less political and religious in nature and instead took on a more purely historical and scientific character. After World War I (1914–1918) and the establishment of the British Mandate, archaeological institutions tended increasingly to be concentrated in the city of Jerusalem.[50]:135–136

In 1913–1914 the Society for the Reclamation of Antiquities was established by the Yishuv's intellectual elite. Among its founder were Avraham Yaakov Brawer, David Yellin and Aharon Meir Mazie. The Society changed its name to the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society in 1920 and later to the Israel Exploration Society.[51][52]

The British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem began operating in 1921, after R. A. Stewart Macalister and Duncan Mackenzie of the Palestine Exploration Fund appealed to the British government for the establishment of a local antiquities authority. Macalister and Mackenzie expressed concern over the dangers posed to archaeological sites on account of the battles being fought throughout the land. Mackenzie was also wary of fellahin raiding archaeological sites and stealing artifacts.[50]:140

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Institute of Archaeology was founded in 1926. In 1934 Hebrew University opened its Department of Archaeology, which it considers "the birthplace of Israeli archaeology."[53] The Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology was established in 1969.[54]

After the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the British Mandatory Department of Antiquities, housed at the Rockefeller Museum, became the Department of Antiquities of the State of Israel. In 1990 the Department of Antiquities became the Israel Antiquities Authority, an autonomous government authority charged with responsibility for all the country's antiquities and authorized to excavate, preserve, conserve and administrate antiquities as necessary.[55][56][57]

Notable Israeli archaeologists

- Eleazar Sukenik (1889–1953)

- Benjamin Mazar (1906–1995), a founding father of Israeli archaeology[58]

- Yigael Yadin (1917–1984)

- Amir Drori (1937–2005), founder of the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1990

New technologies

Israeli archaeologists have developed a method of detecting objects buried dozens of meters underground using a combination of seven technologies, among them echomagnetic soundings, radio transmissions and temperature measurements, able to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant objects such as pipes in the ground.[59]

Politicisation of archaeology

More information: Politics of archaeology in Israel and Palestine

Archaeological research and preservation efforts have been exploited by both Palestinians and Israelis for partisan ends.[60] Rather than attempting to understand "the natural process of demolition, eradication, rebuilding, evasion, and ideological reinterpretation that has permitted ancient rulers and modern groups to claim exclusive possession," archaeologists have instead become active participants in the battle over partisan memory, with the result that archaeology, a seemingly objective science, has exacerbated the ongoing nationalist dispute. Silberman concludes: "The digging continues. Claims and counterclaims about exclusive historical 'ownership' weave together the random acts of violence of bifurcated collective memory." Adam and Moodley conclude their investigation into this issue by writing that, "Both sides remain prisoners of their mythologized past."[60]

As an example of this process, an archaeological tunnel running the length of the western side of the Temple Mount, as it is known to Jews, or the Haram al-Sharif, as it is known to Muslims, became a serious point of contestation in 1996. The tunnel had been in place for about a dozen years, but open conflict broke out after the government of Benjamin Netanyahu decided to open a new entrance to the tunnel from the Via Dolorosa in the Muslim quarter of the Old City. Palestinians and the Islamic Waqf authorities were outraged that the decision was taken without prior consultation. They claimed that the work threatened the foundations of the compound and those of houses in the Muslim quarter and that it was actually aimed at tunnelling under the holy compound complex to find remains of Solomon's Temple, similar to previous accusations in the 1980s. As a result of the rumor, Arabs rioted in Jerusalem and then spread to the West Bank, leading to the deaths of 86 Palestinians and 15 Israeli soldiers.[61]

Damage to sites

From 1948–1967, the Jordanian authorities and military forces engaged in what was described as "calculated destruction" in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City.[62] In a letter to the United Nations, Yosef Tekoa, Israel's representative to the UN, protested Jordan's "policy of wanton vandalism, desecration and violation,"[62] in which all the synagogues in the Old City apart from one were blown up or used as stables.[63] A road was cut through the ancient historic Jewish graveyard on the Mount of Olives, and tens of thousands of tombstones, some dating from as early as 1 BCE, were torn out, broken or used as flagstones, steps and building materials in Jordanian military installations.[64]

The Old City of Jerusalem and its walls were added to the List of World Heritage in Danger in 1982, after it was nominated for inclusion by Jordan.[65] Noting the "severe destruction followed by a rapid urbanization," UNESCO determined that the site met "the criteria proposed for the inscription of properties on the List of World Heritage in Danger as they apply to both 'ascertained danger' and 'potential danger'."[65]

Work carried out by the Islamic Waqf since the late 1990s to convert two ancient underground structures into a new mosque on the Temple Mount damaged archaeological artifacts in the area of Solomon's Stables and the Huldah Gates.[66][67][68] From October 1999 to January 2000, the Waqf authorities in Jerusalem opened an emergency exit to the newly renovated underground mosque, in the process digging a pit measuring 18,000 square feet (1,672 m2) and 36 feet (11 m) deep. The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) expressed concern over the damage sustained to Muslim-period structures within the compound. Jon Seligman, a Jerusalem District archaeologist told Archaeology magazine that, "It was clear to the IAA that an emergency exit [at the Marwani Mosque] was necessary, but in the best situation, salvage archaeology would have been performed first."[69] Seligman said that the lack of archaeological supervision "has meant a great loss to all of humanity. It was an archaeological crime."[67]

Artifacts from the First Temple Period (c. 960 – 586 BC) were destroyed when the thousands of tons of ancient fill from the site were dumped in the Kidron Valley and Jerusalem's municipal garbage dump, making it impossible to conduct archaeological examination.[68]

The 2011 annual report of the Israeli State Comptroller criticized Waqf renovations on the Temple Mount, which were carried out without permits and employed mechanical tools that caused damage to archaeological relics.[70]

In 2012, Bedouin gold-diggers irreversibly damaged the walls of a 2,000-year-old well located under a Crusader structure at Be'er Limon, near Beit Shemesh.[71]

See also

- Near Eastern archaeology

- Biblical archaeology

- Temple Mount Sifting Project

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

- Excavations at the Temple Mount

- Southern Levant

- History of Palestine

- History of Israel

References

- 1 2 Encyclopedia of Zionism and Israel, edited by Raphael Patai, Herzl Press and McGraw-Hill, New York, 1971, vol. I, p.66-71

- ↑ Ussishkin, David (Spring 1982). "Where is Israeli archeology going?". Biblical Archeologist. 45 (2): 93.

- ↑ New fieldwork at Shuqba Cave and in Wadi en-Natuf, Western Judea

- ↑ Dates for Biblical Period follow Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible (New York: Doubleday 1990). ISBN 0-385-23970-X.

- ↑ Israel Finkelstein, Professor of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University Web page

- ↑ "Shifting Ground In The Holy Land", Smithsonian Magazine

- ↑ Urquhart, Conal (2007-05-08). "King Herod's grave uncovered in hilltop fortress". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Israel+beyond+politics/Findings-strengthen-identification-of-Herods%20grave%2019-Nov-2008

- ↑ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Press release from 11 March 2009, "Byzantine period church exposed in Moshav Nes-Harim" Retrieved 24 February 2010

- ↑ Haaretz – article from 11 March 2009, "Archaeologists discover Byzantine-era church in Jerusalem hills" Retrieved 24 February 2010

- ↑ MSNBC – article by Shira Rubin, February 10, 2010 "Byzantine-era street found in Jerusalem" Retrieved 24 February 2010

- ↑ Haaretz, 15 February 2010, "Israel archaeologists unearth 1,400 year-old wine press", Retrieved 3 March 2010

- ↑ Ryan, 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ David Schloen (Spring 1995). "Recent Discoveries at Ashkelon". The Oriental Institute News and Notes. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. No. 145.

- ↑ "Beit Alfa Synagogue National Park (on Kibbutz Hefzibah)". Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Fadi Eyadat (10 September 2007). "Did prehistoric man come from Haifa?". Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Shimon Dar; Negev, Avraham (July–October 1992). "Review: Negev, "The Architecture of Mampsis, 2"". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 83 (1–2): 204–207. doi:10.2307/1455124. JSTOR 1455124.

- ↑ "Old City of Acre". UNESCO. 2001. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ "The Tel Rehov Excavations - 2008". The Hebrew University of Jerusalem: The Institute of Archaeology. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ↑ Jerry Barach (April 22, 2003). "Hebrew University Excavations Strengthen Dating of Archaeological Findings to David, Solomon". Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ "Tel Rehov Excavations - 2007". The Hebrew University of Jerusalem: The Institute of Archaeology Hebrew University. Archived from the original on 2009-04-19. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Oldest known archaeological example of beekeeping discovered in Israel

- ↑ Be'er Sheva

- ↑ The Holy Land, Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, p.438 Oxford University Press, 1998

- ↑ John S. Holladay, Jr. (June 1977). "Untitled Review of "Beer-Sheba I: Excavations at Tel Beer-Sheba 1969-1971 Seasons" by Yohanan Aharoni". Journal of Biblical Literature. 96 (2): 281–284. doi:10.2307/3265886. JSTOR 3265886.

- 1 2 Freedman, 2000, p. 161.

- ↑ "Tel Beersheva National Park". Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Murphy-O'Connor, 1998, p. 438.

- ↑ Hyam Maccoby (September 15, 1995). "Obituary: Benjamin Mazar". The Independent. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Levine, 1998, p. 7.

- ↑ Looking for a wider view of history, Israeli archaeologists are zooming in, Haaretz

- ↑ "Fieldwork: AFOB Online Listing - Tel Gezer Archaeological Project and Field School". Archaeological Institute of America. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- 1 2 Shaye Cohen. "The Credibility of Josephus". PBS. Archived from the original on 29 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Ferguson, 2003, p. 574.

- ↑ Eric Reymond (1998). "A Structural Analysis of Ben Sira 40:11- 44:15". Oriental Institute Research Archives. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Ego et al., 1999, p.230

- ↑ James D. Tabor (1996–1998). "Masada Cave 2001-2002". James D. Tabor. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Yohanan Aharoni (February 1968). "Arad: Its Inscriptions and Temple". The Biblical Archaeologist. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 31 (1): 1–32. doi:10.2307/3211023. JSTOR 3211023.

- 1 2 3 Negev and Gibson, 2001, p. 43.

- ↑ Bromiley, 1995, p. 229.

- ↑ Aharoni, Yohanan (1981). Arad Inscriptions. University of Virginia: Israel Exploration Society. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ↑ Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archaeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company (June 2002) ISBN 978-0-8028-2126-3 p.212

- ↑ King, Philip J.; Lawrence E. Stager Life in Biblical Israel Westminster/John Knox Press,U.S.; 1 edition (19 April 2002) ISBN 978-0-664-22148-5 p.314

- 1 2 Gary A. Rendsburg. "Down with History, Up with Reading: The Current State of Biblical Studies". Department of Jewish Studies at McGill University. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Sharon Zuckerman. "The Kingdom of Hazor in the Late Bronze Age: Chronological and Regional Aspects of the Material Culture of Hazor and its Settlements". Mt. Scopus Radio.

- ↑ Gil Zohar (9 March 2006). "The Mona Lisa of the Galilee beckons to wannabe archaeologists in ancient Sepphoris". Jewish Tribune. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Tzippori

- ↑ Kristin M. Romey (February 29, 2000). "Bulldozers in the Night". Archaeology: A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- ↑ Davis, S.J.M.; Valla, F.R. (1978). "Evidence for the domestication of the dog 12,000 years ago in the Natufian of Israel". Nature. 276 (5688): 608–10. doi:10.1038/276608a0.

- 1 2 Ben-Aryeh, Yehoshua (1999). המוסדות הזרים לארכאולוגיה ולחקירת ארץ־ישראל בתקופת המנדט [The Foreign Institutions of Archeology and Exploration of the Land of Israel During the British Mandate (Tammuz 1999)] (PDF). Cathedra (in Hebrew). Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (92). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ Hasson, Nir (29 March 2013). "Israel's archeological triumphs through the eyes of a man who was always there". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ "About the Israel Exploration Society". Israel Exploration Society. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ "Institute of Archaeology – History". The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ "About us – Institute". Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ Baruch, Yuval; Kudish Vashdi, Rachel. "From the Israel Department of Antiquities to the Founding of the Israel Antiquities Authority". Israel Antiquities Authority. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ "IAA Law". Israel Antiquities Authority. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ Lidman, Melanie (16 January 2013). "Israel Antiquities digitalizes archives". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ "A founding father of Israeli archaeology". Biblical Archaeology Review. Biblical Archaeology Society. 30 (3). May–June 2004.

- ↑ Israeli scientists get heads up on underground archaeological digs, Haaretz

- 1 2 Heibert, Adam (2002). "Peace-Making in Divided Societies – The Israel-South Africa Analogy" (PDF). Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council Publishers. ISSN 1684-2839. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ Ross, 2007, pp. 156–157.

- 1 2 "Letter dated 5 March 1968 from the permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General". United Nations. 6 March 1968. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ Gold, 2007, p. 157

- ↑ Sachar, Howard M. (2007). A History of Israel: from the Rise of Zionism to our Time (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Alfred A Knopf. p. 436. ISBN 978-0-375-71132-9.

...a road was cut through the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, and the headstones of Jewish graves there were used for building purposes, some of them footpaths to army latrines.

- 1 2 "United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Convention Concerning the Protestion of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage". UNESCO. 17 January 1983. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- ↑ Hershel Shanks (18 July 2008). "Opinion:Biblical Destruction". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- 1 2 Michele Chabin (11 July 2006). "Archaeologists Campaign to Stop Desecration of Temple Mount". Jewish United Fund. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- 1 2 Mark Ami-El (1 August 2002). "The Destruction of the Temple Mount Antiquities". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ Kristin M. Romey (March–April 2000). "Jerusalem's Temple Mount Flap". Archaeology: A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America. 53 (2). Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- ↑ 'Waqf Temple Mount excavation damaged archaeological relics'

- ↑ "Gold diggers ravage archeological site", Ynetnews

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Archaeology in Israel. |

- Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) (English homepage)

- 'Producing National identity: Israeli Archaeology museums'. http://www.stateofnature.org/producingNationalIdentity.html

- University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Canaan & Ancient Israel Exhibit)

- Israel Exploration Society

- Israel archaeological sites photos

- Nova special, The Bible's Buried Secrets

- Late Bronze Age II as a period of decline, unrest, disaster, and migration

- Early Israel in Canaan

- In the Roman Period Galilee, the vast majority of inhabitants were Jews. They got along sometimes and also fought

- IAA maps of ongoing excavations in Israel

- Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs - An index of archaeological sites in Israel