Australia–India relations

|

|

Australia |

India |

|---|---|

Australia–India relations are the foreign relations between the Commonwealth of Australia and the Republic of India. Before independence, Australia and India were both part of the British Empire and both are members of the Commonwealth of Nations. They also share political, economic, security, lingual and sporting ties. As a result of British colonisation, cricket has emerged as a strong cultural connection between the two nations, as well as the English language.

History

The ties between Australia and India started immediately following European settlement of Australia in 1788. On the founding of the penal colony of New South Wales, all trade to and from the colony was controlled by the British East India Company, although this was widely flouted.[1]

The Western Australian town of Australind (est. 1841) is a portmanteau word named after Australia and India.[2] Mangalore city is present in both India and Australia (Mangalore, Karnataka, Mangalore, Victoria and Mangalore, Queensland).[3] Australian towns of Cervantes, Northampton and Madura (est. 1876) were used for breeding cavalry horses for the British Indian Army during the late 19th century.[4] The horses were used in the North-West Frontier Province (now Pakistan). Madura's name is likely to have originated from the Tamil Nadu city of Madurai.

After World War II, the Australian government of Ben Chifley supported the independence of India from the British Empire to act as a frontier against communism.[5] Later, under Robert Menzies, Australia supported the admission of India as a Republic to the Commonwealth Nations. In 1950, Menzies became the first Australian Prime Minister to visit India, where he met with the Governor-General Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.[6] As part of the Colombo Plan,[7] many Indian students were sponsored to come and study in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s.

Issues regarding expatriates

In 2007 Mohamed Haneef, an Indian citizen working in Australia, was detained and his visa was cancelled after it was found that he was the second cousin of two men arrested for involvement in terrorist attacks in the UK; one later died of injuries. The Australian Federal Court criticised the Australian Immigration Minister Kevin Andrews for his conduct. The Government of India and the Human Rights Commission were concerned about the treatment of Haneef and the Australian High Commissioner to India was summoned to Ministry of External Affairs in New Delhi.[8][9][10] Haneef won both cases against the Government of Australia, his visa was restored and he was cleared of any alleged links to religious terrorism.[11]

2009–10 attacks on Indian students

In 2009 relations were strained between the two nations by attacks against Indian students, dubbed "curry bashings" by some sections of the media,[12][13] in Australia.[14][15] Police had denied any racial motivation but this was viewed differently by the government in India and students in Australia, leading to high-level meetings with Australian officials.[16] As a result of this, the largest trade union in Bollywood placed a ban on filming in Australia until the Australian government took action.[17] There were also calls in the Indian community to apply a travel ban on Australia.[18] In India, the attacks contributed to stereotypes of a racist Australia.[19][20]

In January 2010, Nitin Garg, an Indian graduate with permanent residence in Australia, was stabbed to death.[21] His attacker, a fifteen-year-old male, was sentenced to thirteen years in 2011. As the only Indian student to die violently in Australia since intense Indian media coverage of the violence started in May 2009, his death was immediately described as a "race attack" by Indian media,[22] sparking strong expressions of anger and anti-Australian sentiment in India. The motive for murder was later found to be the result of a spontaneous attempt to rob Garg of his mobile phone.[23][24]

Indian External Affairs Minister S.M. Krishna described the murder as a "heinous crime on humanity" which was creating "deep anger" in India and "certainly will have some bearing on the bilateral ties between our two countries".[25]

Australian Prime Minister Mr. Kevin Rudd said that "Australia valued its education system and International Students are valued more here in Australia." Mr. Rudd though said that his Govt. has ordered a thorough probe into the attacks and also condemned it in strongest possible terms, and whilst no significant break-through was achieved immediately, during recent years the attacks have been virtually eliminated by strong police enforcement and community involvement. Under the leadership of Prime Minister of Australia Julia Gillard the relations between both the nations have significantly improved on part due to her holistic approach in relations.

Diplomatic relations

India first established a Trade Office in Sydney, Australia in 1941. It is currently represented by a High Commissioner in the embassy at Canberra and Consulate generals in Sydney and Melbourne.[26] Australia has a High Commission in New Delhi, India and Consulates in Mumbai and Chennai.[27]

Besides both being members of the Commonwealth of Nations, both nations are founding members of the United Nations, and members of regional organisations including the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperation and ASEAN Regional forum.

Although Australia and India sometimes had divergent strategic perspectives during the Cold War, in recent years there have been much closer security relations, including a Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation in 2009.[28]

Australia has traditionally supported India's position on Arunachal Pradesh, which is subject to diplomatic disputes between India and the People's Republic of China.[29]

Economic relations[30]

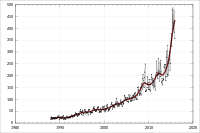

Trade between Australia and India dates back to late 18th century and early 19th century When coal from Sydney and horses from New South Wales were exported to India. As of 2010, bilateral trade between the two countries totaled US$18.7 billion, having grown from A$4.3 billion in 2003. This is expected to rise to touch the mark of US$40 billion by end of year 2016. Trade is highly skewed towards Australia. Australia mainly exports Coal, non-monetary Gold and Copper Ore and agricultural goods to India, while India's chief exports are pearls, precious and semi-precious stones, textiles and clothing, and services [31] Over 97,000 Indian students enrolled in Australia in 2008, representing an education export of A$2 billion.[32]

Military relations

India and Australia conducted a joint naval exercise, termed Malabar 2007, in the Indian Ocean alongside the USA and Japan.[33] In 2007, the Australian government led by John Howard of the Liberal Party agreed in principle to sell uranium to fuel India's nuclear reactors. Howard reversed a previous policy of not selling uranium to non-signatories of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, saying that it would lessen the burden on fossil fuels and encourage India to join the nuclear mainstream. However the Kevin Rudd-led Labor Party government that came to power later that year, rescinded the plan and reverted to the previous policy of not selling to non-NPT signatories.[34] Subsequently, Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard did a backflip in November 2011 and announced that she would push her party to support uranium sales to India.[35] Shortly afterwards, it was reported that Australian foreign minister Kevin Rudd had suggested a security pact between India, Australia and the United States,[36] but this possibility was immediately rejected by Indian authorities.[37] Later, the Australian government denied suggesting such a pact and claimed that Kevin Rudd had been misquoted by media outlets.[38]

Some commentators have suggested that there are considerable opportunities for defence and security cooperation between India and Australia. Potential areas in maritime security include in naval exercises and training (such as use of the Australian Submarine Escape Training facility in Fremantle), greater cooperation in humanitarian and disaster relief operations and search and rescue, maritime border protection and maritime domain awareness. There are also opportunities for greater cooperation between the Indian and Australian armies and air forces (reflecting the greater use of shared platforms).[39]

Prime Ministers Abbott and Modi signed a landmark deal to increase their nations defence relationship in November 2014. Part of the framework for security co-operation includes annual Prime Ministerial meetings and joint maritime exercises. Areas of increased co-operation include counter-terrorism, border control and regional and international institutions.[40] Prime Minister Modi stated in an address to the Australian parliament that "This is a natural partnership emerging from our shared values and interests and strategic maritime locations...Security and defence are important and growing areas of the new India-Australia partnership for advancing regional peace and stability and combating terrorism and transnational crimes"[41]

Sport

Cricket

One of the prominent ties is a shared love of cricket.[42] In 1945, the Australian Services cricket team toured India during their return to Australia for demobilisation, and played against the Indian cricket team. However, those matches were not given Test status. The first Test matches between the countries occurred in 1947–48 after the independence of India, when India toured Australia and played five Tests. Australia won 4–0 and as a result, the Australian Board of Control did not invite the Indians back for two decades, fearing that a series of one-sided contests would lead to financial losses due to lack of spectator interest. In the meantime, Australia toured India in late-1956, 1959–60 and 1964–65.

The 1969–70 series in India, which Australia won, were marred by repeated riots. Some were against the Australian team specifically, after the Indian umpires had ruled against the Indian team, while others were not related to on-field conduct, such as a lack of tickets. Several players were hit by projectiles, including captain Bill Lawry, who was hit with a chair. On one occasion, the Australian bus was stoned. The Communist Party of India (CPI), a major political party in West Bengal, protested against Australian batsman Doug Walters, who they mistakenly thought had fought against the communist Vietcong.[43][44] Around 10,000 communists picketed the Australians' hotel in Calcutta and some eventually broke in and vandalised it.[44][45] Towards the end of the tour, many former Australian players, some of them administrators, called for the tour to be abandoned for safety reasons, saying that cricket should not descend into violence.[45][46]

From 1970 until 1996, Australia only toured India twice for Tests. However, with the financial rise of the Board of Control for Cricket in India, Australia, the country with the most successful playing record in the world, has sought more regular fixtures. Test series have occurred every two years for the last decade, and one-day series even more frequently. Scholarships are also given to talented young Indian cricketers to train at the Australian Cricket Academy.

In January 2008, relations became strained after the second test in Sydney. The match, which ended in a last-minute Australian victory, was marred by a series of umpiring controversies, and belligerent conduct between some of the players. At the end of the match, Harbhajan Singh was charged with racially abusing Andrew Symonds, who had been subjected to monkey chants by Indian crowds on a tour a few months earlier. Harbhajan was initially found guilty and given a ban,[47] and the Board of Control for Cricket in India threatened to cancel the tour. Harbhajan's ban was later repealed upon appeal and the tour continued. Both teams were heavily criticised for their conduct.

Nevertheless, Australian cricketers like Shane Warne, Adam Gilchrist and Brett Lee are immensely popular among the Indian people. Likewise, Sachin Tendulkar is highly regarded among Australian cricket lovers.

Hockey

India and Australia also have strong ties to field hockey which came to both countries with the British military. In India from the mid-19th century, British army regiments played the game which was subsequently picked up by their India regimental counterparts. The country's first hockey club was formed in Calcutta in 1885–86.[48] Hockey in Australia was introduced by British naval officers in the late 19th century.[49] Evidence of the first organised hockey there was the establishment of the South Australian Hockey Association in 1903.

Teams from both countries have been among the top in the world for many years and have therefore frequently encountered each other on the hockey field. India dominated world hockey between 1928 and 1956, with the men's team winning six consecutive Olympic gold medals. The women's team won world titles in 2002, 2003 and 2004. Australia has found success mainly since the late 1970s, with the men's and women's teams winning gold medals at Olympic Games, World Cup, Champion's Trophy and Commonwealth Games meets.

The first international match between the two countries and the first international match played in Australia was at Richmond Cricket Ground in 1935, when the world champion team from India beat Australia 12 goals to one. The visitors featured hockey supremo Dhyan Chand.[50]

Following the partition of India in 1947, brothers Julian, Eric, Cec, Mel and Gordon Pearce, emigrated to Australia from India. All five went on to become successful international players for their adopted country.[51]

See also

- Foreign relations of India

- Foreign relations of Australia

- Indian Australian

- Anti-Indian sentiment in Australia

References

- ↑ Binney, Keith R. "The British East India Company in Early Australia". tbheritage.com. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ↑ Western Australian Land Information Authority. "History of country town names – A". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ↑ "There is a Mangalore in Australia". The Hindu Newspaper. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ "Madura". Sydney Morning herald. 8 February 2004. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Ben Chifley". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ↑ "Menzies on Tour: India". Menzies on Tour: Travelling with Robert Menzies, 1950-1959. eScholarship Research Centre, The University of Melbourne. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ Rao, p. 107.

- ↑ "Haneef gets bail but loses visa". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ "India presses Australia for consular access to detained doctor". Monsters and Critics. 20 July 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ "India should put more pressure on Australia". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 20 July 2007.

- ↑ "Haneef gets visa back". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 December 2007.

- ↑ "'Curry-bashings' strain Australia-India relations". The Economic Times. 31 May 2009.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Kevin Rudd moves to reassure India after attacks". Herald Sun. 2 June 2009.

... an all-night protest... was organised by the Federation of Indian Students of Australia over the violence against Indian students, dubbed "curry bashings".

- ↑ "Indian Students in Melbourne attack Manmohan Singh". IBT Times.

- ↑ "Is Australia racist: Incidents of racial discrimination against the Indian students?". Ceoworld.biz. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "Asia-Pacific | 'Race' attacks spark Indian rally". BBC News. 2009-05-31. Retrieved 2016-10-21.

- ↑ "Bollywood ban follows Indian student attacks; Shane Warne calls for peace". 5 June 2009.

- ↑ "MEA issues guidelines for Australia-bound Indian students". Ndtv.com. 2009-06-13. Retrieved 2016-10-21.

- ↑ "Is attack on Indian students in Australia racism?". Merinews.com. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ Crikey intern Margaret Paul. "wrap: Indian press on Australia's racism". Crikey. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "Man dies after street stabbing". Herald Sun. 2010-01-03. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "Indian youth fatally stabbed in Australia-Rest Of World-World-TIMESNOW.tv - Latest Breaking News, Big News Stories, News Videos". Timesnow.tv. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "Teenager sentenced in Nitin Garg murder case". The Hindu. The Hindu Group. Press Trust of India. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on 19 November 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Lowe, Adrian (22 December 2011). "13 years for Nitin Garg murder". The Age. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 19 November 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ AM South Asia correspondent Sally Sara for AM (2010-01-04). "Indian anger over Footscray 'crime on humanity' - World (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑

- ↑ "About us". Australian High Commission in India. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ↑ David Brewster. "India as an Asia Pacific Power. Retrieved 19 August 2014".

- ↑ "After helping China in AB, Oz says Arunachal part of India". After helping China in ADB, Oz says Arunachal part of India: Expressindia.com. 24 Sep 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ↑ Ashok Sharma (2016-02-25). "Australia-India relations: trends and the prospects for a comprehensive economic relationship | Arndt-Corden Department of Economics". Acde.crawford.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 2016-10-21.

- ↑ "India Australia Bilateral Trade". Indian consulate, Sydney. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ↑ "India country brief". Australian department of foreign affairs and trade. April 2009. Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ↑ "Internet Edition". The Daily Star. 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "Australia bans India uranium sale". BBC News. 15 January 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ↑ "julia gillards uranium backflip opens us door to delhi/". The Australian. 16 November 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Australia backs security pact with U.S., India". Reuters. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "India snubs Oz, says no on pact with US". Daily Pioneer. 2 December 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Australia denies suggesting India-US security pact". BBC News. 2 December 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ David Brewster. "India-Australia security engagement: Opportunities and challenges".

- ↑ Garnaut, John (18 November 2014). "Narendra Modi and Tony Abbott reveal new India-Australia military agreement". The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ↑ "India, Australia vow closer security and trade ties". The West Australian. Agence France-Presse. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ↑ Clare, Nelson (7 January 2008). "Harbhajan Singh handed lengthy ban". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Perry, p. 258.

- 1 2 Mallett, p. 133–134.

- 1 2 Harte, p. 522.

- ↑ Mallett, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Vaidyanathan, Siddhartha (6 January 2008). "Harbhajan gets three-match ban". Cricinfo. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Hockey in India". asiarooms.com Travel Guide. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ↑ "History of Hockey". Hockey Victoria. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ↑ "India Meets Australia At Hockey". The Age. 19 August 1935.

- ↑ "Julian Pearce – Hockey". Sport Australia Hall of Fame. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of Australia and India. |

- Grand Stakes: Australia’s Future between China and India by Rory Medcalf, Strategic Asia 2011-12: Asia Responds to Its Rising Powers - China and India (September 2011)

- Harte, Chris (1993). A History of Australian Cricket. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-98825-4.

- Mallett, Ashley (2009). One of a Kind: The Doug Walters Story. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74175-029-6.