Republic of Biak-na-Bato

| Republic of Biak-na-Bato | ||||||||||||

| Repúbliká ng̃ Biak-na-Bató República de Biac-na-Bató | ||||||||||||

| Unrecognized state | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

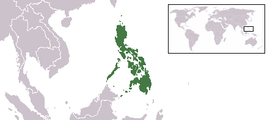

| ||||||||||||

Territory claimed by the Republic of Biak-na-Bato in Asia | ||||||||||||

| Capital | San Miguel, Bulacan | |||||||||||

| Languages | Spanish, Tagalog | |||||||||||

| Government | Republic | |||||||||||

| President | Emilio Aguinaldo | |||||||||||

| Vice President | Mariano Trías | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Philippine Revolution | |||||||||||

| • | Established | November 1, 1897 | ||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | December 14, 1897[1] 1897 | ||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||

| • | 1897 | 300,000 km² (115,831 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

The Republic of Biak-na-Bato (Tagalog: Repúbliká ng̃ Biak-na-Bató, Spanish: República de Biac-na-Bató), officially referred to in its constitution as the Republic of the Philippines (Tagalog: Repúbliká ng̃ Filipinas, Spanish: República de Filipinas), was the first republic ever declared in the Philippines by revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo and his fellow revolutionaries. Despite its successes, including the establishment of the Philippines' first ever constitution, the republic lasted just over a month. It was disestablished by a peace treaty signed by Aguinaldo and the Spanish Governor-General, Fernando Primo de Rivera which included provision for exile of Aguinaldo and key associates to Hong Kong.

Government

The constitution of the Republic of Biak-na-Bato was written by Felix Ferrer and Isabelo Artacho, who copied the Cuban Constitution of Jimaguayú nearly word-for-word.[2] It provided for the creation of a Supreme Council, which was created on November 2, 1897, with the following as officers having been elected:[3][4]

History

The initial concept of the republic began during the latter part of the Philippine revolution, when the leader of the Katipunan, Emilio Aguinaldo, became surrounded by Spanish forces at his headquarters in Talisay, Batangas. Aguinaldo slipped through the Spanish cordon and, with 500 picked men, proceeded to Biak-na-Bató,[5] a wilderness area at the town of San Miguel, Bulacan (now parts of San Miguel, San Ildefonso and Doña Remedios in Bulacan).[6] When news of Aguinaldo's arrival there reached the towns of central Luzon, men from the Ilocos provinces, Nueva Ecija, Pangasinan, Tarlac, and Zambales renewed their armed resistance against the Spanish.[5]

Unable to persuade the revolutionaries to give up their arms, Governor-General Primo de Rivera issued a decree on July 2, 1897, which prohibited inhabitants from leaving their villages and towns. Contrary to his expectations, they continued fighting. Within days, Aguinaldo and his men planned the establishment of a Republic. Aguinaldo issued a proclamation from his hideout in Biak-na-Bato entitled "To the Brave Sons of the Philippines", in which he listed his revolutionary demands as:

- the expulsion of the Friars and the return to the Filipinos of the lands which they had appropriated for themselves;

- representation in the Spanish Cortes;

- freedom of the press and tolerance of all religious sects;

- equal treatment and pay for Peninsular and Insular civil servants;

- abolition of the power of the government to banish civil citizens;

- legal equality of all persons.[7]

On November 1, 1897, the provisional constitution for the Biak-na-Bato Republic was signed.[8] The preamble of the constitution included the statement that

The separation of the Philippines from the Spanish monarchy and their formation into an independent state with its own government called the Philippine Republic has been the end sought by the Revolution in the existing war, begun on the 24th of August, 1896; and therefore, in its name and by the power delegated by the Filipino people, interpreting faithfully their desires and ambitions, we, the representatives of the Revolution, in a meeting at Biac-na-bato, Nov. 1st. 1897, unanimously adopt the following articles for the Constitution of the State.[9]

By the end of 1897, Governor-General Primo de Rivera accepted the impossibility of quelling the revolution by force of arms. In a statement to the Cortes Generales, he said, "I can take Biak-na-Bato, any military man can take it, but I can not answer that I could crush the rebellion." Desiring to make peace with Aguinaldo, he sent emissaries to Aguinaldo seeking a peaceful settlement. Nothing was accomplished until Pedro A. Paterno, a distinguished lawyer from Manila, volunteered to act as negotiator.

On August 9, 1897, Paterno proposed a peace based on reforms and amnesty to Aguinaldo. In succeeding months, practicing shuttle diplomacy, Paterno traveled back and forth between Manila and Biak-na-Bato carrying proposals and counterproposals. Paterno's efforts led to a peace agreement called the Pact of Biak-na-Bato. This consisted of three documents, the first two being signed on December 14, 1897, and the third being signed on December 15; effectively ending the Republic of Biak-na-Bato.[10]

In 1899, Aguinaldo wrote in retrospect that the principal conditions of the pact were:[11]

(1) That I would, and any of my associates who desired to go with me, be free to live in any foreign country. Having fixed upon Hongkong as my place of residence, it was agreed that payment of the indemnity of $800,000 (Mexican) should be made in three installments, namely, $400,000 when all the arms in Biak-na-Bató were delivered to the Spanish authorities; $200,000 when the arms surrendered amounted to eight hundred stand; the final payment to be made when one thousand stand of arms shall have been handed over to the authorities and the Te Deum sung in the Cathedral in Manila as thanksgiving for the restoration of peace. The latter part of February was fixed as the limit of time wherein the surrender of arms should be completed.

(2) The whole of the money was to be paid to me personally, leaving the disposal of the money to my discretion and knowledge of the understanding with my associates and other insurgents.

(3) Prior to evacuating Biak-na-Bató the remainder of the insurgent forces under Captain-General Primo de Rivera should send to Biak-na-Bató two General of the Spanish Army to be held as hostages by my associates who remained there until I and a few of my compatriots arrived in Hongkong and the first installment of the money payment (namely, four hundred thousand dollars) was paid to me.

(4) It was also agreed that the religious corporations in the Philippines be expelled and an autonomous system of government, political and administrative, be established, though by special request of General Primo de Rivera these conditions were not insisted on in the drawing up of the Treaty, the General contending that such concessions would subject the Government to severe criticism and even ridicule.[11]

The Mother of Biak-na-Bato

Trinidad Tecson: Katipunan of San Miguel, Bulacan.

Legacy

- Emilio Aguinaldo Cave at the Park (site of his chair made of stone and hide out)

- The Historical Marker

- Aguinaldo Mural - Constitution of Biak-na-Bato (1897)

- Mural facade - Shrine

- Aguinaldo passed the Hanging Bridge

- Memorial (Aguinaldo/Katipuneros used the Panday for their weapons, arms)

- Facade

- Facade of the Monument, Memorial-Marker of the Pact

- The Memorial

- NHI Marker, 1973 Biak-na-Bato Memorial

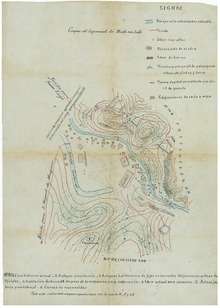

- Biak-na-Bato National Park Map of Emilio Aguinaldo's Cave and protected areas

- Mural of the Republic of Biak-na-Bato (Casa Real Museum, Malolos City

On November 16, 1937, a 2,117 hectares (8.17 sq mi) block in the Biak-na-Bato area was declared a national park by Manuel L. Quezon in honor of the Republic.[12] In the 1970s, Ferdinand Marcos issued orders guiding mineral prospecting and exploitation in government reservation which impacted the park boundaries. On April 11, 1989, Corazon Aquino issued Proclamation No. 401, which re-defined the boundaries of the Biak-na-Bato National Park. The proclamation set aside 952 hectares (3.68 sq mi) hectares as mineral reservation, 938 hectares (3.62 sq mi) hectares as watershed reservation and 480 hectares (1.9 sq mi) hectares as forest reserve.[12]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Don Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (23 September 1899), "Chapter II. The Treaty of Biak-na-bató", True Version of the Philippine Revolution, Authorama: Public Domain Books, retrieved 23 September 2008

- ↑ Ogonsotto, Rebecca Ramilo; Ogonsotto, Reena R. Philippine History Module-based Learning I' 2002 Ed. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 139. ISBN 978-971-23-3449-8.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, pp. 183–184

- ↑ "1897 Biac-na-Bato Constitution". [The Corpus Juris. November 1, 1897.

- 1 2 Agoncillo 1990, p. 182

- ↑ Biak na Bato, Newsflash.org.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, pp. 182–183

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p. 183

- ↑ Constitution of Biak-na-Bato, Wikisource.

- ↑ Zaide 1994, p. 252

- 1 2 Aguinaldo 1899 Chapter II. The Treaty of Biak-na-bató

- 1 2 Carmela Reyes, Bulaceños want Biak-na-Bato declared a protected area (26 August 2007), Philippine Daily Inquirer.

References

- Agoncillo, Teodoro C. (1990) [1960], History of the Filipino People (8th ed.), Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, ISBN 971-8711-06-6

- Aguinaldo, Emilio (1899), "True Version of the Philippine Revolution", Authorama Public Domain Books

- Zaide, Sonia M. (1994), The Philippines: A Unique Nation, All-Nations Publishing Co., ISBN 971-642-071-4

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- A complete collection of Philippine Constitutions

- Biak-na-Bato Constitution (English)

- Biak-na-Bato Constitution (Spanish)

- Biak-na-Bato Constitution (Tagalog)

- Natural Springs and Caves of Biak Na Bato, philippinesinsider.com

- Biak na Bato, waypoints.ph

- Biak na Bato, txtmania.com