Bulawayo

| Bulawayo koBulawayo | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

|

View of Bulawayo's Central Business District (CBD) from Pioneer House by Prince Phumulani Nyoni. The CBD is 5.4 square kilometres and is in a grid pattern with 17 avenues and 11 streets | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): 'City of Kings', 'Skies', 'Bluez' or 'Bulliesberg' | |||

| Motto: Siyephambili | |||

Location in the Bulawayo Province | |||

Bulawayo Location in the Bulawayo Province | |||

| Coordinates: 20°10′12″S 28°34′48″E / 20.17000°S 28.58000°ECoordinates: 20°10′12″S 28°34′48″E / 20.17000°S 28.58000°E | |||

| Country | Zimbabwe | ||

| Province | Bulawayo | ||

| District | City of Bulawayo | ||

| Settled | 1840 | ||

| Incorporated (town) | 1897 | ||

| Incorporated (city) | 1943 | ||

| Divisions | 4 Districts, 29 Wards, 156 Suburbs | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Provincial Municipality | ||

| • Mayor | Martin Moyo | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 1,706.8 km2 (659.0 sq mi) | ||

| • Water | 129.3 km2 (49.9 sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 993.5 km2 (383.6 sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 1,706.8 km2 (659.0 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation[1] | 1,358 m (4,455 ft) | ||

| Population (2016) | |||

| • City | 1,200,337 | ||

| • Density | 700/km2 (1,800/sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 1,205,675 | ||

| • Urban density | 2,305/km2 (5,970/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | SAST (UTC+2) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+2) | ||

| Area code(s) | 9 | ||

| Climate | Cwa | ||

| Website |

citybyo | ||

Bulawayo is the second-largest city in Zimbabwe after the capital Harare, with, as of the 2012 census, a population of 653,337.[2] It is located in Matabeleland, 439 km (273 mi) southwest of Harare, and is now treated as a separate provincial area from Matabeleland. The capital of Matabeleland North is now Lupane, as Bulawayo is a stand-alone province.

Colloquially Bulawayo is also known by various names, these being the 'City of Kings', 'Skies', 'Bluez', 'Bulliesberg' or 'KoNtuthu ziyathunqa' – a isiNdebele phrase for "a place that continually exudes smoke". This name arose from the city's historically large industrial base.[3] The majority of the Bulawayo's population belongs to the Ndebele ethnic and language group.

For a long time in Zimbabwe's history Bulawayo was regarded as the industrial centre of Zimbabwe and the city served as the hub to the country's rail network with the National Railways of Zimbabwe headquartered there because of its strategic position near Botswana and South Africa.[3] It is the nearest large city to Hwange National Park, Matobo National Park and Victoria Falls.

History

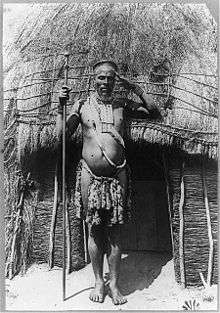

The city was founded by the Ndebele king, Lobengula the son of King Mzilikazi kaMatshobana who settled in modern-day Zimbabwe around the 1840s after the Ndebele people's great trek from Zululand. The name Bulawayo comes from the isiNdebele word KoBulawayo meaning 'a place where he is being killed.' It is thought that at the time of the formation of the city, there was a civil war and a group of Ndebeles not aligned to Prince Lobengula were fighting him as they felt he was not the heir to the throne, hence he gave his capital the name 'where he (the prince) is being killed'. It is said that when King Lobengula named the place "KoBulawayo" his generals asked "who is being killed mtanenkosi (prince)?" and he replied "Yimi umntwanenkosi engibulawayo", meaning "its me the prince who is being killed". At the time Lobengula was just a prince fighting to ascend his father's (Mzilikazi) throne. It was common at the time for people to refer to Bulawayo as "KoBulawayo UmntwaneNkosi" "a place where they are fighting or rising against the prince". The name Bulawayo is imported from Nguniland which is a place once occupied by the Khumalo people. The place still exists and it is next to Richards Bay.

In the 1860s the city was further influenced by European intrigue and many colonial powers cast covetous eyes on Bulawayo and the land surrounding it. Britain made skilful use of private initiative in the shape of Cecil Rhodes and the Chartered Company to disarm the suspicion of her rivals. Lobengula once described Britain as a chameleon and himself as the fly.[4]

During the 1893 Matabele War, the invasion by British South Africa Company troops forced King Lobengula to evacuate his followers, after first detonating munitions and setting fire to the town.[5] BSAC troops and white settlers occupied the ruins. On 4 November 1893, Leander Starr Jameson declared Bulawayo a settlement under the rule of the British South Africa Company. Cecil Rhodes ordained that the new settlement be founded on the ruins of Lobengula's royal kraal, which is where the State House stands today. In 1897, the new town of Bulawayo acquired the status of municipality, Lt. Col. Harry White became one of the first mayors,[6] and in 1943 Bulawayo became a city.

Siege

At the outbreak of the Second Matabele War, in March 1896, Bulawayo was besieged by Ndebele forces, and a laager was established there for defensive purposes. The Ndebele had experienced the brutal effectiveness of the British Maxim guns in the First Matabele War, so they never mounted a significant attack against Bulawayo, even though over 10,000 Ndebele warriors could be seen near the town. Rather than wait passively, the settlers mounted patrols, called the Bulawayo Field Force, under legendary figures such as Frederick Selous and Frederick Russell Burnham. These patrols rode out to rescue any surviving settlers in the countryside, and attacked the Ndebele. Within the first week of fighting, twenty men of the Bulawayo Field Force were killed and another fifty were wounded.

During the siege, conditions inside Bulawayo quickly deteriorated. By day, settlers could go to homes and buildings within the town, but at night they were forced to seek shelter in the much smaller laager. Nearly 1,000 women and children were crowded into the small area and false alarms of attacks were common. The Ndebele made a critical error during the siege in neglecting to cut the telegraph lines connecting Bulawayo to Mafikeng. This gave both the besieged Bulawayo Field Force and the British relief forces, coming from Salisbury and Fort Victoria, now Harare and Masvingo respectively 300 miles to the north, and from Kimberley and Mafeking 600 miles to the south, far more information than they would otherwise have had. Once the relief forces arrived in late May 1896, the siege was broken and an estimated 50,000 Ndebele retreated into their stronghold, the Matobo Hills near Bulawayo. Not until October 1896 would the Ndebele finally lay down their arms.

Modern city

In recent years, Bulawayo has experienced a sharp fall in living standards coinciding with the severe economic crisis affecting the country. Today it is home to the strongest opposition to the government of Robert Mugabe. The main problems include poor investment and widespread unemployment. Water shortages due to lack of expansion in facilities and supplies have become steadily more acute since 1992. Cholera broke out in 2008.

Bulawayo City Council

Although controlled by the main opposition party MDC-T, the council has managed to stand out as the leading municipality in Zimbabwe in terms of service delivery to its residents, through various campaigns engineered by the city council such as the #mycitymypride campaign and #keepbyoclean on social media, these have been met with positive responses by residents and other stakeholders within the city. In recent years Bulawayo has now been widely perceived as the cleanest city in Zimbabwe due to the council's effective waste management strategy, although like all major cities and towns in the country Bulawayo faces water challenges, but the situation within the city has been described as manageable. In 2015 the City of Bulawayo was praised for its town planning which unlike major urban areas such as Harare and Chitungwiza has not been marred by corruption and problems such as illegal settlements.

Geography

Topography

The city sits on a plain that marks the Highveld of Zimbabwe and is close to the watershed between the Zambezi and Limpopo drainage basins. The land slopes gently downwards to the north and northwest. The southern side is hillier, and the land becomes more broken in the direction of the Matobo Hills to the south.

Climate

Due to its relatively high altitude, the city has a subtropical climate despite lying within the tropics. Under the Köppen climate classification, Bulawayo features a humid subtropical climate (Cwa), though it is a drier version of the climate. The mean annual temperature is 19.16 °C (66.44 °F),[7] similar to Pretoria at a similar altitude but almost 600 km (373 mi) farther south. As with much of southern and eastern Zimbabwe, Bulawayo is cooled by a prevailing southeasterly airflow most of the year, and experiences three broad seasons: a dry, cool winter season from May to August; a hot dry period in early summer from late August to early November; and a warm wet period in the rest of the summer, early November to April. The hottest month is October, which is usually the height of the dry season. The average maximum temperature ranges from 21 °C (70 °F) in July to 30 °C (86 °F) in October. During the rainy season, daytime maxima are around 26 °C (79 °F). Nights are always cool, ranging from 8 °C (46 °F) in July to 16 °C (61 °F) in January.

The city's average annual rainfall is 594 mm (23 in), which supports a natural vegetation of open woodland, dominated by Combretum and Terminalia trees. Most rain falls in the December to February period, while June to August is usually rainless. Being close to the Kalahari Desert, Bulawayo is vulnerable to droughts and rainfall tends to vary sharply from one year to another. In 1978, 888 mm (35 in) of rain fell in the three months up to February (February 1944 is the wettest month on record with 368mm) while in the three months ending February 1983, only 84 mm (3 in) fell.

| Climate data for Bulawayo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.7 (98.1) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

33.0 (91.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.2 (90) |

35.0 (95) |

36.7 (98.1) |

37.2 (99) |

35.2 (95.4) |

37.2 (99) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27.7 (81.9) |

27.2 (81) |

27.1 (80.8) |

25.9 (78.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.1 (79) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.8 (71.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.9 (66) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

7.2 (45) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.0 (59) |

16.0 (60.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 10.0 (50) |

9.4 (48.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

0.0 (32) |

−3.9 (25) |

0.0 (32) |

0.0 (32) |

1.4 (34.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

7.2 (45) |

8.9 (48) |

−3.9 (25) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 117.8 (4.638) |

104.6 (4.118) |

51.4 (2.024) |

33.3 (1.311) |

7.0 (0.276) |

2.2 (0.087) |

1.0 (0.039) |

1.4 (0.055) |

7.0 (0.276) |

38.4 (1.512) |

91.1 (3.587) |

120.3 (4.736) |

575.5 (22.657) |

| Average rainy days | 10 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 51 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 71 | 70 | 62 | 56 | 54 | 48 | 43 | 41 | 43 | 55 | 63 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 244.9 | 212.8 | 251.1 | 252.0 | 279.0 | 267.0 | 288.3 | 300.7 | 288.0 | 272.8 | 237.0 | 226.3 | 3,119.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.9 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 8.5 |

| Source #1: World Meteorological Organization[8] NOAA (sun and mean temperature, 1961–1990)[9] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes and humidity)[10] | |||||||||||||

Water scarcity

Bulawayo's physical geography has led to the presence of varying degrees water scarcity throughout distinct suburbs within the city. The geographical factors causing water scarcity are the area's high elevation and the arid environment of the Matabeleland. Bulawayo provides residents with water by using a system of dams, treatment plants, and reservoirs; however, due to the short supply, many residents obtain their water from wells and boreholes. The low accessibility to water in residential areas, along with the water quality within these areas, correlate with the spread of diseases within each respective area. In particularly, neighborhoods with relatively high population density and areas that are at higher physical elevations have lower availability to water. According to studies taken in 2007 and 2008, the densely populated suburb of Mpopoma has significantly lower water consumption than that of the less densely populated Khumalo, which is situated on lower ground. In addition to receiving less water than Khumalo, Mpopoma also has a higher proportion of water-related diseases.

Environmental and sanitation circumstances have detrimental effects on water quality. Sources such as groundwater and tap water are subject to pollution due to waste from burst sewers contaminating them. Samples taken from well water from the Pumula and Robert Sinyoka suburbs show that well water maintain levels of coliform higher than the Standards Association of Zimbabwe and World Health Organization give.[11][12]

Demographics

Population census controversy

The population of Bulawayo, according to the 2012 national census, stands at 653 337;[13] however, this figure has been rejected by the Bulawayo City Council authority with Councillor Martin Moyo claiming an anti-Bulawayo conspiracy to under fund projects in the city.[14][15]

The population of the city according to metropolitan council sources is closer to 1,5 million and a more closer and estimated figure being 1,2 million. Reports have alluded to the de-industrialization of the city as the reason for its population decline, a claim which was rubbished as council officials referred to the fact that in 1992 were the city's population stood at 620 936 the city has grown in the number of households due to urban expansion. City authorities also laid claim to the fact that the current water challenges facing the city were also as a result of an increasing population despite the economic challenges facing the city.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1992 | 620,936 | — |

| 2002 | 676,650 | +9.0% |

| 2012 | 653,337 | −3.4% |

| Source: Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) | ||

Economy

Bulawayo has long been known as the industrial hub of Zimbabwe. It has a large manufacturing presence, and large industries such as Merlin Textiles, Zimbabwe Engineering Company (Zeco), Hubert Davies, Radar Metal Industries, National Blankets, G & D Shoes, Merlin, Tregers Group, Stewarts & Lloyds, Hunyani Holdings, and Cold Storage Commission. However, some of these companies have either moved operations to Harare or no longer exist altogether which has crippled Bulawayo's economy. The industries are deserted and the infrastructure has since been left to deteriorate, further deterring investors from operating in the city. The reason for the city's de-industrialization has been heralded to be the lack of infrastructure to support the size of the city and its operations and an unreliable source of water and the collapse of the rail infrastructure which was a core reason of placing industry in Bulawayo to begin with. Many locals argue that it is because of marginalisation they experience against the government due to cultural differences between the Shona in Harare and the Ndebele Proper in Bulawayo because the National railways of Zimbabwe (Headquarters Bulawayo) is a government parastatal and as such should have been thriving had it not been for embezzlement of allocated funds by company executives who are believed to be Shona. The water issue is not new and had brought about the "help a thirsty Matabele" initiative of the 1970s and the Matabeleland Zambezi Water Project which would put an end to the water issue in Matabeleland was drafted; however, this project was put on hold soon after independence. these allegations have all been labelled hogwash by the relevant authorities; however, they have only fueled the secessionist initiative into a general opinion. Before the collapse of Zimbabwe's rail infrastructure, Bulawayo was an important transport hub, providing rail links between Botswana, South Africa and Zambia and promoting the city's development as a major industrial centre. The city still contains most of what remains of Zimbabwe's heavy industry and food processing capability including a Thermal Power Station which resumed operations in February 2011 after a capitalisation deal with the Government of Botswana where Bulawayo would supply 45 Megawatts in three years. Like many parts of the country, Bulawayo has for the past ten years seen a huge drop in service delivery and an increase in unemployment due to the number of resignations of people seeking better prospects across the border. Many people resorted to farming, mining and the black market for sustenance, while others depended on the little foreign currency that would be sent by family in other countries. However, with the introduction of the multi-currency system in 2009, a new approach is seen by investors in the city who admire the already-available infrastructure and the huge workforce and Bulawayo as great prospects for the future and is set to once again contribute greatly to the economy of Zimbabwe. The city is served by Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo International Airport which has been expanded a number of times to cope with the influx of visitors into the region. The Edgars clothing stores are headquartered in Bulawayo. The Rovos rail run luxury train, Pride of Africa makes a stop in Bulawayo for pick up and dropping off passengers. Bulawayo is situated along the Trans-African Highway network important trade route of Cairo – Cape Town Highway. Most of the city's industries are privately owned, especially in the transport sector.

Important buildings and infrastructure

These include

- Ascot Centre

- NRZ building

- Bulawayo Centre

- Nesbitt Castle

- Fidelity Life Centre

- National University of Science and Technology

- Mhlahlandlela Government Complex

Government

Mayors since independence

| Mayor | Party | Time in office |

|---|---|---|

| Martin Moyo (Incumbent) | MDC-T | 2013 –[16] |

| Patrick Thaba-Moyo | MDC-T | 2008–2013[17] |

| Japhet Ndabeni Ncube | MDC, MDC-M | 2001–2008[18] |

| Abel Siwela | ZANU-PF | 1996–2000 died in office[18] |

| Joshua Teke Malinga | ZANU-PF | 1993–1995? |

| I. Gadhlula | ZANU-PF | 1992-1993 |

| N. Sidanile | ZANU-PF | 1991-1992 |

| Dennis Madulane Ndlovu | ZANU-PF | 1990-1991 |

| A.L. Ncube | ZANU-PF | 1989-1990 |

| J.M. Ndlovu | ZANU-PF | 1988–1989 |

| Nicholas Joel Mabodoko | PF-ZAPU | 1985–1988 |

| Enos M. Mdlongwa | PF-ZAPU | 1983–1985 |

| Naison Khutshwekhaya Ndlovu | PF-ZAPU | 1981–1983 |

Mayors during UDI

| Mayor | Party | Time in office |

|---|---|---|

| Mike Constandinos | 1979–1981 | |

| D.J. Rowland | 1978-1979 | |

| Mrs. J.L. Sharland | 1977-1978 | |

| E.Hoyle | 1976-1977 | |

| L. Sexon | 1975-1976 | |

| C.M. Scott | 1974-1975 | |

| E.D. Gordon | 1973-1974 | |

| R.S. Harris | 1972-1973 | |

| H. Coronel | 1971-1972 | |

| T.H. Doyle | 1970-1971 | |

| J.M. Logan | 1969-1970 | |

| J. Goldwasser | 1968–1969[19] | |

| W.R. Kinleyside | 1967-1968 | |

| A. Menashe | 1965–1967[19] | |

Mayors during the colonial period

| Mayor | Party | Time in office |

|---|---|---|

| A.C. Dold | 1964-1964 | |

| Aubrey M. Butcher | 1963-1964 | |

| S.H. Millar | 1962-1963 | |

| J.G. Pain | 1961-1962 | |

| M.E. Brett | 1960-1961 | |

| S.H. Millar | 1959-1960 | |

| M.M. McNellie (OBE, MM) | 1957-1959 | |

| J.W. Phillips (OBE) | 1955-1957 | |

| J.M. MacDonald | 1953-1955 | |

| C.M. Newman (OBE, MC, VD, ED) | 1951-1953 | |

| J.H. Butcher | 1949-1951 | |

| H.A. Holmes | 1947-1949 | |

| Donald Macintyre (CBE) | Southern Rhodesia Labour Party | 1944–1947[20] |

| E.J. Dawies | 1942-1944 | |

| D.W. Young | 1940-1942 | |

| T.A.E. Holdengarde | 1938-1940 | |

| Donald Macintyre (CBE) | Southern Rhodesia Labour Party | 1936–1938[20] |

| C.M. Harris | 1934–1936[19] | |

| T.A.E. Holdengarde | 1933-1934 | |

| W. Maver | 1932-1933 | |

| W.H. Peard | 1929–1932[20] | |

| H.B. Ellenbogen | 1927–1929[19][20] | |

| H.R. Barbour | 1924-1927 | |

| J.H. Bookless | 1923-1924 | |

| James Cowden | Rhodesia Party | 1919–1923 four consecutive terms[20][21] |

| W.J. Atterbury | 1918-1919 | |

| George Stewart | 1917-1918 | |

| W.J. Atterbury | 1915-1917 | |

| W.B. Bucknall | 1914-1915 | |

| Alex Fraser | 1913-1914 | |

| Lt. Col. Walter Baxendale | 1912-1913 | |

| Alex Fraser | 1911-1912 | |

| E. Basch | 1907–1911[19] | |

| E.F. Philip | 1906-1907 | |

| Lt. Col. Walter Baxendale | 1904-1906 | |

| J.E. Scott | 1902-1904 | |

| John Kerr | 1901-1902 | |

| William H. Haddon | 1900-1901 | |

| Lt. Col. Henry Frederick "Harry" White (DSO) | 1899–1900 returned to military service[6] | |

| Charles Holland | 1898-1899 | |

| I.G. Hirschler | 1897–1898[19] |

Newspapers

- B-Metro

- The Chronicle

- Newsday

- Southern Eye

- The Sunday News

- The Sunday Times

- Umthunywa

Twin towns – sister cities

Bulawayo is twinned with:

-

Aberdeen, Scotland

Aberdeen, Scotland -

Durban, South Africa

Durban, South Africa -

Polokwane, South Africa

Polokwane, South Africa -

Katima Mulilo, Namibia

Katima Mulilo, Namibia -

Francistown, Botswana

Francistown, Botswana  . Livingstone, Zambia

. Livingstone, Zambia

Culture and recreation

Sports

Bulawayo is home to the Queens Sports Club and Bulawayo Athletic Club, two of the three grounds in Zimbabwe where test match cricket has been played. It is also home to Hartsfield Rugby grounds where many international Test matches have been played. Hartsfield was developed by Reg Hart, after whom the grounds were named, and on which field many of southern Africa's greatest rugby players have competed. It is home to two large football teams, Highlanders and Zimbabwe Saints. Other football teams include Bantu Rovers, Chicken Inn, How Mine and Quelaton.

Other important sporting and recreational facilities include

- Barbourfields Stadium

- Zimbabwe International Trade Fair Grounds

- Kumalo Hockey Stadium

- Ascot Racecourse

- Khami Ruins

- White City Stadium

Museums

Bulawayo has a number of museums of national importance, including the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe, National Gallery, Bulawayo and the Bulawayo Railway Museum.

Parks

There are a number of parks in Bulawayo, including

- Centenary Park

- Barham Green

- Hillside Dams Conservancy

- Mabukweni

Suburbs and districts

| No | Suburb/location | Origin of name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ascot | Adjoining the Bulawayo Ascot race-course |

| 2 | Barbour Fields | The suburb was named after a former mayor, H. R. Barbour, who during the colonial era was greatly interested in the welfare of the indigenous people. There is a place called Barbour in Argyll & Bute. Barbour is a Scottish family name, though it was apparently first recorded on the English side of the border, in Cumberland and Northumberland. The father of Scottish vernacular poetry, John Barbour (1320–1395), is best remembered for his epic poem "The Brus", telling the story of King Robert I. The origin of the name is occupational (a cutter of hair as well as an extractor of teeth during the Middle Ages). |

| 3 | Barham Green | The suburb was named after two people. The first was a former Bulawayo City Councillor [who later became an Alderman] Mrs. M. E. Barham, M.B.E. and the other was Rev. Rufus Green. The two people were critical in the establishment of this suburb. During the colonial Rhodesia era, the suburb was designated for the Coloured community. |

| 4 | Beacon Hill | Also known as Beryl Drive, reference is made to fact that it is the high point of the suburbs and possesses the areas with the highest marking beacon at its summit. |

| 5 | Bellevue | The suburb was named after the estate name. It is sometimes spelled Belle Vue. The origin of this universally-popular place name is ultimately French – "beautiful view". |

| 6 | Belmont | |

| 7 | Belmont Industrial Area | The area was named after a former Bulawayo City Engineer, Mr. Kinmont. |

| 8 | Bradfield | The suburb was named after Mr. Edwin Eugene Bradfield, a pioneer. |

| 9 | Burnside | This area used to be a portion of former town council area, and used to be part of Matsheumhlope Farms. The name is derived from the reference to the River Matsheumhlophe. "Burn" is a Scottish and northern English word for a stream. |

| 10 | Cement | This was named after the surrounding industrial area, responsible for the making of cement. |

| 11 | Cowdray Park | |

| 12 | Donnington | |

| 13 | Donnington West | |

| 14 | Douglasdale | The Douglas family, descendants of William de Duglas (late 12th century), was one of the most powerful in Scotland. |

| 15 | Eloana | |

| 16 | Emakhandeni | Emakhandeni is the isiNdebele name for Fort Rixon, which was the area where the regiment aMakhanda were located. eMakhandeni is the locative term. |

| 17 | Emganwini | Reference is made to the plentiful amarula trees in the vicinity. |

| 18 | Enqameni | |

| 19 | Enqotsheni | |

| 20 | Entumbane | This is where King Mzilikazi was buried. It is one of the dozens of high density suburbs of Bulawayo, commonly referred to as the "Western Suburbs". The first disturbances that led to the Gukurahundi were sparked in Entumbane, hence the term "Impi ye Ntumbane" that refers to the disturbances. |

| 21 | Estate name | |

| 22 | Estate name | |

| 23 | Fagadola | |

| 24 | Famona | The suburb was named after Famona, one of the daughters of King Lobengula. It means jealousy or envy must end (literally, "die"). |

| 25 | Fortunes Gate (including Mtaba Moya) | The suburb's name comes from the original property name, and the gates are those of the original market building. |

| 26 | Four Winds | The suburb name comes from the original property name, the first house was on top of a hill. |

| 27 | Glencoe | This name is etched into the Scottish psyche as the bleak glen in the Highlands where, in 1692, a party of MacDonald men, women and children were treacherously massacred by the Campbells, who were acting under government orders. |

| 28 | Glengary | The suburb was named after its estate name. The "Glengarry" bonnet is an oblong woollen cap, popular amongst pipe bands. |

| 29 | Glenville (including Richmond South) | The suburb was named after its estate name. |

| 30 | Granite Park | |

| 31 | Greenhill | The suburb's name is a reference to scenery and topography. |

| 32 | Gwabalanda | Named after a Ndebele chief, Gwabalanda Mathe |

| 33 | Harrisvale | |

| 34 | Helenvale | |

| 35 | Highmount | |

| 36 | Hillcrest | The suburb's name comes from the reference to topography. It is Greenhill's crest. |

| 37 | Hillside | The suburb's name is a reference to topography (Greenhill's slope). |

| 38 | Hillside South | The suburb's name comes from its position as the south facing slope of Greenhill. |

| 39 | Hume Park | "Hume"/"Home" is a Lowland Scottish family name. |

| 40 | Hyde Park | The name originates from the large amount of residents who trace their ancestry to England. |

| 41 | Ilanda | Ndebele name for the egret |

| 42 | Iminyela | This is the name of a type of tree common in the area. |

| 43 | Intini | The name was given as a commemoration to the Mhlanga family, who originally set out with the Khumalo family under Mzilikazi as gratitude to their contribution to the Ndebele Kingdom, Mthwakazi. The Ntini is the totem of the Mhlanga-Mabuya clan. |

| 44 | Jacaranda | This is a reference to the jacaranda trees. |

| 45 | Kelvin (Industrial area, includes North East and West) | The area was named in reference to a suburb of Glasgow. It takes its name from the River Kelvin, a tributary of the River Clyde. |

| 46 | Kenilworth | The suburb was named after its estate name. |

| 47 | Khumalo | The suburb was named after the Royal Clan of the Matabele. |

| 48 | Khumalo North | This is a reference to the position of Kumalo suburb. |

| 49 | Kilallo | |

| 50 | Killarney | |

| 51 | Kingsdale | |

| 52 | Lakeside | Lakeside is the stretch of water at the junction of the Old Essexvale Road and the road to the suburb of Waterford, and then on to Hope Fountain Mission. |

| 53 | Lobengula | Itisnamed after the second and last Matabele King, Lobengula. |

| 54 | Lobenvale | The suburb's name is derived from a combination of King Lobengula's name and Umguza Valley. |

| 55 | Lochview | The suburb's name is in reference to Lakeside Dam and is famous in the city for its large Scottish residents and the Scottish style houses. According to the Bulawayo City Suburb Names website, the suburb was named in reference to Lakeside Dam. |

| 56 | Luveve | Named after Ndebele chief Luveve; established in 1935 |

| 57 | Mabuthweni | The suburb's name means "where the soldiers are"; the name was given in reference to a bachelors' quarters. |

| 58 | Magwegwe | The suburb name is named after Magwegwe, who was one of the significant people in King Lobengula's royal Bulawayo town. |

| 59 | Magwegwe North | This is a reference to the position relative to that of Magwegwe. |

| 60 | Magwegwe West | This is a reference to the position relative to that of Magwegwe. |

| 61 | Mahatshula | Mahatshula is named after one of the Ndebele Indunas, Mahatshula Ndiweni. |

| 62 | Makokoba | The suburb got its name from the actions of Mr. Fallon, who used walk around with a stick. The name comes from the word "umakhokhoba" which was how the locals referred to Fallon, meaning "the little old man who walks with a stick". The word actually describes the noise of the stick hitting the ground, ko-ko-ko, or the doors. It is the oldest African dwelling in the city. Political activism was rife in the pre-Zapu era. |

| 63 | Malindela | The suburb was named after the mother of Faluta, who was the mother of Lobengula, i.e., after Lobengula's maternal grandmother. |

| 64 | Manningdale | It is named after the developer of the suburb. |

| 65 | Marlands | |

| 66 | Matsheumhlope | The name comes from the association with the river ("White Stones"). White stones in Ndebele Proper and Zulu language are "amatshe amhlope". |

| 67 | Matshobana | The suburb was named after Matshobana, who was a chief of the Khumalo clan and more significantly he was the father of Mzilikazi, the founder of the Ndebele Kingdom. |

| 68 | Montgomery | It is named after Bernard Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, a decorated British Army commander. |

| 69 | Montrose | The suburb was named by the estate developers, and street names are of many Cotswolds villages and towns. |

| 70 | Morningside | |

| 71 | Mpopoma | The name comes from a descriptive Ndebele name for the area, which was derived from the sound the Mpopoma River makes when flowing. |

| 72 | Munda | The Tonga name for a plot of land on which people would farm |

| 73 | Mzilikazi | The suburb was named after the founder of uMthwakazi, King Mzilikazi. It is a stone's throw away from Barbourfields suburb, separated by a road called Ambulance Drive that leads to one of Zimbabwe's large hospitals, Mpilo. |

| 74 | New Luveve | Reference is made to the suburb Luveve; see Luveve suburb. |

| 75 | Newsmansford | |

| 76 | Newton | Estate name |

| 77 | Newton West | Reference to position (Newton) |

| 78 | Nguboyenja | Named after Lobengula's son and heir |

| 79 | Njube | Named after one of Lobengula's sons |

| 80 | Nketa | It is named after the Traditional Heritage Site of Nketa Hill on which King Lobengula assembled his entire kingdom and divided its citizens according to cultural ethnicity and different stages of incorporation into three groups the Zansi which is Xhosa for "south", referring to the people who left the Zulu Kingdom originally, the Enhla or Nxele, which referred to the second mass incorporated group, which was the Swati, Pedi, and Sotho, with whom they settled in Mhlahlandela 1. The final group was the Hole /ˈxɒli, which constituted of the Shona, Kalanga and Bakwena. Most historians argued that this was clear evidence of Lobengula's lack of foresight and political tact as he was literally undoing what his father had spent his lifetime trying to achieve, a unified kingdom with a single identity. |

| 81 | Nkulumane | One of the sons of King Mzilikazi and heir, founder of the Matebele kingdom |

| 82 | North End | Reference to the direction of the suburb |

| 83 | North Lynne | |

| 84 | North Trenance | Reference to position relative to that of Trenance |

| 85 | Northlea | |

| 86 | Northvale | Former town council area; reference to position and (Umguza) valley |

| 87 | Ntaba Moyo | |

| 88 | Orange Grove | |

| 89 | Paddonhurst | Named after Major Cecil Paddon, O.B.E. (pioneer) |

| 90 | Parklands | Estate name; Park Lands estate A (portion of original grant to Dominican Sisters) |

| 91 | Parkview | Situated on the location adjacent to the Centenary Park and proposed location of Bulawayo Zoo |

| 92 | Pelandaba | Phelandaba translates as "the matter is concluded", a reference to the successful conclusion to the struggle for security. |

| 93 | Pumula | Phumula means "a resting place", reference to the fact that many have built homes there to retire to. |

| 94 | Pumula South | Named in reference to relative position of Pumula |

| 95 | Queens Park | A reference to the Queen and the three main roads – Victoria, Alexandra and Elizabeth |

| 96 | Queens Park East | A reference to the position relative to that of Queen Park |

| 97 | Queens Park West | A reference to the position relative to that of Queen Park |

| 98 | Queensdale | |

| 99 | Rangemore | The suburb adopted the original estate name. |

| 100 | Raylton | The suburb adopted the original estate name. |

| 101 | Richmond | |

| 102 | Riverside | Derived from the original estate name, which was in reference to the Umguza River |

| 103 | Romney Park | The suburb was named after George Romney, a British painter. |

| 104 | Sauerstown | Named after Dr. Han Sauer, original owner of the land |

| 105 | Selbourne Park | Named after the main road of Selbourne Avenue, now called L. Takawira Avenue, facing Ascot Mansions |

| 106 | Sizinda | Battle regiment of Mzilikazi of the Matabele |

| 107 | Southdale | |

| 108 | Souththwold | The suburb was named by the estate developers, and street names are of many Cotswolds villages and towns. |

| 109 | Steeldale | Composite name referring to industry |

| 110 | Suburbs | This was the first suburb and retained that name. |

| 111 | Sunninghill | After British royal residence (given to present Queen at time of marriage) |

| 112 | Sunnyside | Chosen from list of suggested names |

| 113 | Tegela | The name is derived from a Ndebele word ukwethekela meaning "to visit". |

| 114 | The Jungle | |

| 115 | Thorngrove | The suburb's name came from the large number of mimosa (thorn) trees in the area. |

| 116 | Trenance | |

| 117 | Tshabalala | This is the "isibongo" or praise name for Lobengula's mother, Fulata, who was of Swazi extraction. |

| 118 | Tshabalala Extension | Extension in reference to the suburb of Tshabalala |

| 119 | Umguza Estate | Named after the Umguza River which runs through it |

| 120 | Upper Rangemore | Name in reference to Rangemore suburb |

| 121 | Waterford | |

| 122 | Waterlea | |

| 123 | West Somerton | |

| 124 | Westgate | |

| 125 | Westondale | |

| 126 | Willsgrove | |

| 127 | Windsor Park | Named after English town or Guildford Castle grounds |

| 128 | Woodlands | Chosen from a list of suggested names |

| 129 | Woodville | |

| 130 | Woodville Park |

Schools and colleges

In Bulawayo, there are 128 primary and 48 secondary schools.[24]

Primary schools

| No. | School Name |

|---|---|

| 1. | Amaswazi Primary School |

| 2. | Amaveni Primary School |

| 3. | Babambeni Primary School |

| 4. | Baines Infant School |

| 5. | Baines Junior |

| 6. | Barham Green Primary School |

| 7. | Carmel Primary School |

| 8. | Coghlan Primary School |

| 9. | Dominican Convent Primary School, Bulawayo |

| 10. | Dumezweni Primary School |

| 11. | Emakhandeni Primary School |

| 12. | Fairbridge Primary School |

| 13. | Fusi Primary School |

| 14. | Gampu Primary School |

| 15. | Godlwayo Primary School |

| 16. | Helemu Primary School |

| 17. | Henry Low Primary School |

| 18. | Hillside Infant School |

| 19. | Hillside Junior School |

| 20. | HQ 1 Brigade Primary School |

| 21. | Hugh Beadle Primary School |

| 22. | Induba Primary School |

| 23. | Infant School |

| 24. | Ingubo Primary School |

| 25. | Ingwegwe Primary School |

| 26. | Inkanyezi Primary School |

| 27. | Insukamini Primary School |

| 28. | Intunta Primary School |

| 29. | Inzwananzi Primary School |

| 30. | John Slaven Primary School |

| 31. | Josiah Chinamano Primary School |

| 32. | King George VI Memorial School |

| 33. | Kumalo Primary School |

| 34. | Lobengula Primary School |

| 35. | Lobengula Primary School |

| 36. | Lochview Primary School |

| 37. | Losikeyi Primary School |

| 38. | Lotshe Primary School |

| 39. | Lukhanyiso Primary School |

| 40. | Luveve Primary School |

| 41. | Mabhukudwana Primary School |

| 42. | Mafakela Primary School |

| 43. | Mafela Primary School |

| 44. | Magwegwe Primary School |

| 45. | Mahlabezulu |

| 46. | Mahlathini Primary School |

| 47. | Malindela Primary School |

| 48. | Manondwana Primary School |

| 49. | Manyewu Primary School |

| 50. | Maphisa Primary School |

| 12. | Masiyephambili Junior School |

| 51. | Masuku Primary School |

| 52. | Maswazi Primary School |

| 53. | Matshayisikova Primary School |

| 54. | Mawaba Primary School |

| 55. | Mazwi Primary School |

| 56. | Mbizo Primary School |

| 57. | McKeurten Primary School |

| 58. | Mganwini Primary School |

| 59. | Mgiqika Primary School |

| 60. | Mgombane Primary School |

| 61. | Mhali Primary School |

| 62. | Milton Junior School |

| 63. | Mkhithika Primary School |

| 64. | Moray Primary School |

| 65. | Mpumelelo Primary School |

| 66. | Mthombowesizwe Primary School |

| 67. | Mtshane Primary School |

| 68. | Mtshede Primary School |

| 69. | Mtshingwe Primary School |

| 70. | Mzilikazi Primary School |

| 71. | Newmansford Primary School |

| 72. | Ngwalongwalo Primary School |

| 73. | Nketa Primary School |

| 74. | Nkulumane Primary School |

| 75. | Ntabeni Primary School |

| 76. | Ntshamathe Primary School |

| 77. | Nyamande Primary School |

| 78. | Petra Primary School |

| 79. | Phelandaba SDA Primary School |

| 80. | Queen Elizabeth II Primary School |

| 81. | Rangemore Primary School |

| 82. | Robert Tradgold Primary School |

| 83. | Rose Camp Primary School |

| 84. | Senzangakhona Primary School |

| 86. | Sigombe Primary School |

| 87. | St. Bernards R.C Primary School |

| 88. | St. Patricks R.C Primary School |

| 89. | St. Thomas Aquinas Primary School |

| 90. | Tategulu Primary School |

| 91. | Tennyson Primary School |

| 92. | Thembiso Primary School |

| 93. | Thomas Rudland Primary School |

| 94. | Trenance Primary School |

| 95. | Waterford Primary School |

| 96. | Whitestone School |

| 97. | Woodville Primary School |

| 98. | Zulukandaba Primary School |

Secondary and high schools

| No. | School Name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Amhlope Pumula No. 2 Secondary School |

| 2 | Amhlophe Secondary School |

| 3 | Bulawayo Adventist Secondary School (BASS) |

| 4 | Bulawayo Technical School (now Gifford High School) |

| 5 | Christian Brothers College, Bulawayo |

| 6 | Cowdray Park Secondary School |

| 7 | Dominican Convent High School, Bulawayo |

| 8 | Emakhandeni Secondary School |

| 9 | Entumbane Secondary School |

| 10 | Eveline Girls High School |

| 11 | Falcon College |

| 12 | Founders High School |

| 13 | Gifford High School |

| 14 | Girls' College |

| 15 | Hamilton High School |

| 16 | Ihlati Secondary School |

| 17 | Inyanda High School |

| 18 | Lobengula Secondary School |

| 19 | Luveve High School |

| 20 | Magwegwe Secondary School |

| 21 | Mandwandwe Secondary School |

| 22 | Masotsha Secondary School |

| 23 | Milton High School |

| 24 | Montrose Girls High School |

| 25 | Mpopoma High School |

| 26 | Msitheli Secondary School |

| 27 | Mzilikazi High School |

| 28 | Njube Secondary School |

| 29 | Nketa Secondary School |

| 30 | Nkulumane Secondary School |

| 31 | Northlea High School |

| 32 | Petra High School |

| 33 | Premier High School |

| 34 | Pumula High School |

| 35 | Sikhulile Secondary School |

| 36 | Sizane High School |

| 37 | Sobukazi High School |

| 38 | St Bernard's R.C. High School |

| 39 | St. Columbus High School |

| 40 | Townsend High School |

| 41 | Mncumbatha Secondary School |

Schools outside Bulawayo

- Falcon College – outskirts of Bulawayo, Esigodini

- Plumtree School – 88 km (55 miles) from Bulawayo, in Plumtree

- John Tallach High School

- Inyathi High School - 70km from Bulawayo

Colleges and universities

- Academy of Learning Business Training College

- ADAS Tuition Centre - ITEC registered beauty school and BTEC (EDEXCEL) Centre

- Bulawayo Polytechnic College

- Gwanda State University, Gwanda

- Hillside Teachers College

- Lupane State University, Lupane

- National University of Science and Technology, Zimbabwe

- Solusi University

- Speciss College

- UNISA

- United College of Education (UCE)

- Zimbabwe Distance Education College (Zdeco)

- ZOU, Zimbabwe Open University

Literature

The city of Bulawayo serves as the backdrop for the French novel Sale Hiver à Bulawayo, by Soline de Thoisy (2011). It is also the starting point for the 1925 novel by Agatha Christie, The Secret of Chimneys, in which the main character is leading tours, and meets up with an old friend who gives him two jobs to do in England.

Natives and residents

- John H Abeles, physician, medical investor, philanthropist

- Marshall P. Baron, painter

- Erich Bloch, economist and columnist

- Robin Brown, cricketer

- NoViolet Bulawayo, writer

- Warren Carne, cyclist

- Cornelius Chada, engineer

- Winnie Madamombe, IT specialist

- Charlene, Princess of Monaco, wife of Albert II, Prince of Monaco

- Brian Chikwava, writer and musician

- Charles Coghlan, lawyer, first Premier of Southern Rhodesia; honoured by burial near Cecil Rhodes's grave, at "World's View" in the Matopo Hills near Bulawayo

- David Coltart, former Minister of Education, Sports, Arts and Culture (2008–2013)

- Charles Coventry, cricketer

- Kirsty Coventry, world-record swimmer

- Chelsy Davy, former girlfriend of Prince Harry

- Graham Edwards, cricketer

- Lucia Evans, winner of the 2006 Irish TV talent show You're A Star, born in Bulawayo

- Stanley Fischer, governor of the Bank of Israel

- Duncan Fletcher, cricketer, former coach of England national cricket team and current coach of Indian national cricket team

- Norman Geras, professor of political philosophy, University of Manchester; writes normblog, a widely read UK blog

- Humphrey Gibbs, GCVO, KCMG, farmer, Governor of the colony of Southern Rhodesia (1959–1970)

- Graeme Hick, Zimbabwean-born English cricketer

- Kubi Indi, development activist and businesswoman

- Tendayi Jembere, actor

- Graham Johnson, pianist, recognised as one of the world's leading vocal accompanists; world authority on the song repertoire

- Doris Lessing, novelist, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature

- Cont Mhlanga, playwright and founder of Amakhosi Theater

- August Musarurwa, composer of the tune "Skokiaan"

- Benjani Mwaruwari, footballer and former Zimbabwe team captain; also turned out for Blackburn Rovers and Manchester City

- Peter Ndlovu, footballer, former Zimbabwe team captain; considered to be the best Zimbabwean player of all time

- Lewin Nyatanga, Zimbabwean-born Welsh footballer

- Alexander Pines, professor of chemistry, University of California, Berkeley

- Nick Price, former world number one golfer, World Golf Hall of Fame member

- Ramadu, musician

- Surendran Reddy, musician, composer and performer

- Rozalla, dance music performer

- Ron Sandler, CEO of Lloyd's of London; Chairman of Northern Rock bank

- Allan Savory, biologist

- Shingai Shoniwa, rock musician

- Reward Sibanda, theologian

- Alexander McCall Smith, CBE, FRSE, writer and Emeritus Professor of Medical Law at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland; author of The No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency series

- Joseph Sonnabend, physician, researcher, part of the team which discovered interferon

- Heath Streak, cricketer and former captain of Zimbabwe team; current bowling coach of the Bangladesh team

- Yvonne Vera, award-winning author

- Sean Williams, Zimbabwean cricketer

References

- ↑ Google Earth

- ↑ Zimbabwe at GeoHive

- 1 2 "Industrial empire Bulawayo reduced to a ghost town". mg.co.za. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ A.R.C.B. Review: A Russian Look at Rhodesia. The Journal of African history, Vol. 2. No 1 (1961), pp. 161–162 available on JSTOR

- ↑ Thorpe, C. Limpopo to Zambesi, London 1951 p.51

- 1 2 "D.S.O.". London Gazette. 19 April 1901. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ GISS Climate data, Average annual temperature 1971 to 2001

- ↑ "World Weather Information Service – Bulawayo". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bulawayo Airport Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Bulawayo (Goetz-Observatorium) / Simbabwe" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Nyemba, Anesu; Manzungu, Emmanuel (2010). "The impact of water scarcity on environmental health in selected residential areas in Bulawayo City, Zimbabwe". http://www.sciencedirect.com/. Retrieved Nov 11, 2016. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Nyemba, Anesu. "The impact of water scarcity on environmental health in selected residential areas in Bulawayo City, Zimbabwe." Physics and chemistry of the earth 35.13 (2010):823-827. Web.

- ↑ "Provincial Report – Bulawayo" (PDF). Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ↑ "Bulawayo Census Outrage". chronicle.co.zw. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ↑ "Storm Over Bulawayo Census Results". thestandard.co.zw. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ↑ "New mayors for Kwekwe, Bulawayo, Gweru and Masvingo". NewZimbabwe.com. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ↑ "Mayor urged to hit ground running". SOuthern Eye. 18 September 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- 1 2 Zimbabwe Election Support Network (2001). Bulawayo Mayoral and Council By-Elections Report (Report). Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Bulawayo". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ranger, Terence (2010). Bulawayo Burning: The Social History of a Southern African City, 1893–1960. Boydell & Brewer.

- ↑ "The Age of Ai". To The Victoria Falls. 212. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ http://www.bulawayo1872.com

- ↑ http://www.rampantscotland.com/placenames/placename_bulawayo.htm

- ↑ Makoni, Albert (6 September 2007). "Health disaster looms in Bulawayo". The Zimbabwe Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bulawayo. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bulawayo. |