Machine

A machine is a tool containing one or more parts that uses energy to perform an intended action. Machines are usually powered by chemical, thermal, or electrical means, and are often motorized. Historically, a power tool also required moving parts to classify as a machine. However, the advent of electronics has led to the development of power tools without moving parts that are considered machines.[1]

A simple machine is a device that simply transforms the direction or magnitude of a force, but a large number of more complex machines exist. Examples include vehicles, electronic systems, molecular machines, computers, television, and radio.

Etymology

The word machine derives from the Latin word machina,[1] which in turn derives from the Greek (Doric μαχανά makhana, Ionic μηχανή mekhane "contrivance, machine, engine",[2] a derivation from μῆχος mekhos "means, expedient, remedy"[3]). The word mechanical comes from the same Greek roots. However, the Ancient Greeks probably have borrowed the word "mekhane" from the ancient Hebrews. The word "Mekhonot" plural and "Mekhona" singular mentioned in the Hebrew Bible - Torah; these "Mekhonot" were the ten contraption on four wheels that stood at the Holy Temple of Jerusalem, built by King Solomon-(2 Chronicles 4:14). The ancient Greeks were familiar with the Hebrew Scriptures and language, and often borrowed words and terms.

A wider meaning of "fabric, structure" is found in classical Latin, but not in Greek usage.

This meaning is found in late medieval French, and is adopted from the French into English in the mid-16th century.

In the 17th century, the word could also mean a scheme or plot, a meaning now expressed by the derived machination. The modern meaning develops out of specialized application of the term to stage engines used in theater and to military siege engines, both in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The OED traces the formal, modern meaning to John Harris' Lexicon Technicum (1704), which has:

- Machine, or Engine, in Mechanicks, is whatsoever hath Force sufficient either to raise or stop the Motion of a Body... Simple Machines are commonly reckoned to be Six in Number, viz. the Ballance, Leaver, Pulley, Wheel, Wedge, and Screw... Compound Machines, or Engines, are innumerable.

The word engine used as a (near-)synonym both by Harris and in later language derives ultimately (via Old French) from Latin ingenium "ingenuity, an invention".

History

Perhaps the first example of a human made device designed to manage power is the hand axe, made by chipping flint to form a wedge. A wedge is a simple machine that transforms lateral force and movement of the tool into a transverse splitting force and movement of the workpiece.

The idea of a simple machine originated with the Greek philosopher Archimedes around the 3rd century BC, who studied the Archimedean simple machines: lever, pulley, and screw.[4][5] He discovered the principle of mechanical advantage in the lever.[6] Later Greek philosophers defined the classic five simple machines (excluding the inclined plane) and were able to roughly calculate their mechanical advantage.[7] Heron of Alexandria (ca. 10–75 AD) in his work Mechanics lists five mechanisms that can "set a load in motion"; lever, windlass, pulley, wedge, and screw,[5] and describes their fabrication and uses.[8] However the Greeks' understanding was limited to statics (the balance of forces) and did not include dynamics (the tradeoff between force and distance) or the concept of work.

During the Renaissance the dynamics of the Mechanical Powers, as the simple machines were called, began to be studied from the standpoint of how much useful work they could perform, leading eventually to the new concept of mechanical work. In 1586 Flemish engineer Simon Stevin derived the mechanical advantage of the inclined plane, and it was included with the other simple machines. The complete dynamic theory of simple machines was worked out by Italian scientist Galileo Galilei in 1600 in Le Meccaniche ("On Mechanics").[9][10] He was the first to understand that simple machines do not create energy, they merely transform it.[9]

The classic rules of sliding friction in machines were discovered by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), but remained unpublished in his notebooks. They were rediscovered by Guillaume Amontons (1699) and were further developed by Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1785).[11]

Types

Mechanical

The word mechanical refers to the work that has been produced by machines or the machinery. It mostly relates to the machinery tools and the mechanical applications of science. Some of its synonyms are automatic and mechanic.

Simple machines

The idea that a machine can be broken down into simple movable elements led Archimedes to define the lever, pulley and screw as simple machines. By the time of the Renaissance this list increased to include the wheel and axle, wedge and inclined plane.

Engines

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert energy into useful mechanical motion.[13][14] Heat engines, including internal combustion engines and external combustion engines (such as steam engines) burn a fuel to create heat, which is then used to create motion. Electric motors convert electrical energy into mechanical motion, pneumatic motors use compressed air and others, such as wind-up toys use elastic energy. In biological systems, molecular motors like myosins in muscles use chemical energy to create motion.

Electrical

Electrical means operating by or producing electricity, relating to or concerned with electricity. In other words, it means using, providing, producing, transmitting or operated by electricity.

Electrical machine

An electrical machine is the generic name for a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy, converts electrical energy to mechanical energy, or changes alternating current from one voltage level to a different voltage level.

Electronic machine

Electronics is the branch of physics, engineering and technology dealing with electrical circuits that involve active electrical components such as vacuum tubes, transistors, diodes and integrated circuits, and associated passive interconnection technologies. The nonlinear behaviour of active components and their ability to control electron flows makes amplification of weak signals possible and is usually applied to information and signal processing. Similarly, the ability of electronic devices to act as switches makes digital information processing possible. Interconnection technologies such as circuit boards, electronic packaging technology, and other varied forms of communication infrastructure complete circuit functionality and transform the mixed components into a working system.

Computing machines

Computers are machines to process information, often in the form of numbers. Charles Babbage designed various machines to tabulate logarithms and other functions in 1837. His Difference engine can be considered an advanced mechanical calculator and his Analytical Engine a forerunner of the modern computer, though none were built in Babbage's lifetime.

Modern computers are electronic ones. They use electric charge, current or magnetization to store and manipulate information. Computer architecture deals with detailed design of computers. There are also simplified models of computers, like State machine and Turing machine.

Molecular machines

Study of the molecules and proteins that are the basis of biological functions has led to the concept of a molecular machine. For example, current models of the operation of the kinesin molecule that transports vesicles inside the cell as well as the myosin molecule that operates against actin to cause muscle contraction; these molecules control movement in response to chemical stimuli.

Researchers in nano-technology are working to construct molecules that perform movement in response to a specific stimulus. In contrast to molecules such as kinesin and myosin, these nanomachines or molecular machines are constructions like traditional machines that are designed to perform in a task.

Machine elements

Machines are assembled from standardized types of components. These elements consist of mechanisms that control movement in various ways such as gear trains, transistor switches, belt or chain drives, linkages, cam and follower systems, brakes and clutches, and structural components such as frame members and fasteners.

Modern machines include sensors, actuators and computer controllers. The shape, texture and color of covers provide a styling and operational interface between the mechanical components of a machine and its users.

Mechanisms

Assemblies within a machine that control movement are often called "mechanisms." [15][16] Mechanisms are generally classified as gears and gear trains, cam and follower mechanisms, and linkages, though there are other special mechanisms such as clamping linkages, indexing mechanisms and friction devices such as brakes and clutches.

For more details on mechanical machines see Machine (mechanical) and Mechanical systems.

Controllers

Controllers combine sensors, logic, and actuators to maintain the performance of components of a machine. Perhaps the best known is the flyball governor for a steam engine. Examples of these devices range from a thermostat that as temperature rises opens a valve to cooling water to speed controllers such the cruise control system in an automobile. The programmable logic controller replaced relays and specialized control mechanisms with a programmable computer. Servo motors that accurately position a shaft in response to an electrical command are the actuators that make robotic systems possible.

Impact

Industrial Revolution

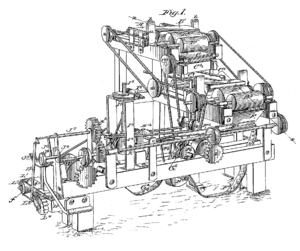

The Industrial Revolution was a period from 1750 to 1850 where changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times. It began in the United Kingdom, then subsequently spread throughout Western Europe, North America, Japan, and eventually the rest of the world.

Starting in the later part of the 18th century, there began a transition in parts of Great Britain's previously manual labour and draft-animal–based economy towards machine-based manufacturing. It started with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal.[17]

Mechanization and automation

Mechanization or mechanisation (BE) is providing human operators with machinery that assists them with the muscular requirements of work or displaces muscular work. In some fields, mechanization includes the use of hand tools. In modern usage, such as in engineering or economics, mechanization implies machinery more complex than hand tools and would not include simple devices such as an un-geared horse or donkey mill. Devices that cause speed changes or changes to or from reciprocating to rotary motion, using means such as gears, pulleys or sheaves and belts, shafts, cams and cranks, usually are considered machines. After electrification, when most small machinery was no longer hand powered, mechanization was synonymous with motorized machines.[18]

Automation is the use of control systems and information technologies to reduce the need for human work in the production of goods and services. In the scope of industrialization, automation is a step beyond mechanization. Whereas mechanization provides human operators with machinery to assist them with the muscular requirements of work, automation greatly decreases the need for human sensory and mental requirements as well. Automation plays an increasingly important role in the world economy and in daily experience.

Automata

An automaton (plural: automata or automatons) is a self-operating machine. The word is sometimes used to describe a robot, more specifically an autonomous robot. An alternative spelling, now obsolete, is automation.[19]

See also

- Darwin among the Machines

- Desiring-production

- History of technology

- Machine (mechanical)

- Technology

- Automaton

References

- 1 2 The American Heritage Dictionary, Second College Edition. Houghton Mifflin Co., 1985.

- ↑ "μηχανή", Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus project

- ↑ "μῆχος", Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus project

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac (1988), Understanding Physics, New York, New York, USA: Barnes & Noble, p. 88, ISBN 0-88029-251-2.

- 1 2 Chiu, Y. C. (2010), An introduction to the History of Project Management, Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers, p. 42, ISBN 90-5972-437-2

- ↑ Ostdiek, Vern; Bord, Donald (2005). Inquiry into Physics. Thompson Brooks/Cole. p. 123. ISBN 0-534-49168-5. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ↑ Usher, Abbott Payson (1988). A History of Mechanical Inventions. USA: Courier Dover Publications. p. 98. ISBN 0-486-25593-X.

- ↑ Strizhak, Viktor; Igor Penkov; Toivo Pappel (2004). "Evolution of design, use, and strength calculations of screw threads and threaded joints". HMM2004 International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms. Kluwer Academic publishers. p. 245. ISBN 1-4020-2203-4. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- 1 2 Krebs, Robert E. (2004). Groundbreaking Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 163. ISBN 0-313-32433-6. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ↑ Stephen, Donald; Lowell Cardwell (2001). Wheels, clocks, and rockets: a history of technology. USA: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 85–87. ISBN 0-393-32175-4.

- ↑ Armstrong-Hélouvry, Brian (1991). Control of machines with friction. USA: Springer. p. 10. ISBN 0-7923-9133-0.

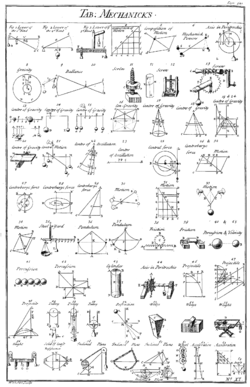

- ↑ Chambers, Ephraim (1728), "Table of Mechanicks", Cyclopaedia, A Useful Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, London, England, Volume 2, p. 528, Plate 11.

- ↑ "Motor". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

a person or thing that imparts motion, esp. a contrivance, as a steam engine, that receives and modifies energy from some natural source in order to utilize it in driving machinery.

- ↑ Dictionary.com: (World heritage) "3. any device that converts another form of energy into mechanical energy to produce motion"

- ↑ Reuleaux, F., 1876 The Kinematics of Machinery, (trans. and annotated by A. B. W. Kennedy), reprinted by Dover, New York (1963)

- ↑ J. J. Uicker, G. R. Pennock, and J. E. Shigley, 2003, Theory of Machines and Mechanisms, Oxford University Press, New York.

- ↑ Beck B., Roger (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, Illinois: McDougal Littell.

- ↑ Jerome (1934) gives the industry classification of machine tools as being "other than hand power". Beginning with the 1900 U.S. census, power use was part of the definition of a factory, distinguishing it from a workshop.

- ↑ "U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, Patent# 40891, Toy Automation". Google Patents. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

Further reading

- Oberg, Erik; Franklin D. Jones; Holbrook L. Horton; Henry H. Ryffel (2000). Christopher J. McCauley; Riccardo Heald; Muhammed Iqbal Hussain, eds. Machinery's Handbook (26th ed.). New York: Industrial Press Inc. ISBN 0-8311-2635-3.

- Reuleaux, Franz (1876). The Kinematics of Machinery. Trans. and annotated by A. B. W. Kennedy. New York: reprinted by Dover (1963).

- Uicker, J. J.; G. R. Pennock; J. E. Shigley (2003). Theory of Machines and Mechanisms. New York: Oxford University Press.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Machines. |