Casey Stengel

| Casey Stengel | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Stengel in 1953 | |||

| Right fielder / Manager | |||

|

Born: July 30, 1890 Kansas City, Missouri | |||

|

Died: September 29, 1975 (aged 85) Glendale, California | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| September 17, 1912, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| May 19, 1925, for the Boston Braves | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .284 | ||

| Home runs | 60 | ||

| Runs batted in | 535 | ||

| Managerial record | 1,905–1,842 | ||

| Winning % | .508 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

As player

As manager | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Inducted | 1966 | ||

| Election Method | Veterans Committee | ||

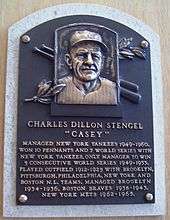

Charles Dillon "Casey" Stengel (/ˈstɛŋɡəl/; July 30, 1890 – September 29, 1975), nicknamed "The Old Perfessor", was an American Major League Baseball right fielder and manager. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966.

Stengel was born in Kansas City, Missouri, and originally nicknamed "Dutch", a common nickname at that time for Americans of German ancestry. After his major league career began, he acquired the nickname "Casey", which originally came from the initials of his hometown ("K. C."), which evolved into "Casey", influenced by the wide popularity of the poem Casey at the Bat. In the 1950s, sportswriters dubbed him with yet another nickname, "The Old Professor" (or "Perfessor"), for his sharp wit and his ability to talk at length on anything baseball-related.

Although his baseball career spanned a number of teams and cities, he is primarily associated with clubs in New York City. Between playing and managing, he is the only person to have worn the uniforms of all four of New York's major league clubs. He was the first of four men to manage both the New York Yankees and New York Mets (Yogi Berra, Dallas Green, and Joe Torre are the others). Like Joe Torre, he also managed the Braves and the Dodgers. Stengel ended his baseball career as the beloved manager for the then expansion New York Mets, which won over the hearts of New York partly due to the unique character of their veteran leader.

Early life

Stengel was born on July 30, 1890, in Kansas City, Missouri. He played sandlot baseball as a child, and also played baseball, football and basketball at Central High School. His basketball team won the city championship, while the baseball team won the state championship.[1]

Stengel had no particular vision of sports as a long-term profession, but, rather, had aspirations of a career in dentistry. As described in his autobiography, on pages 58 and 75–76, he saved enough money from his early minor league experience in 1910–1911 to train to become a dentist. He had some problems due to the lack of left-handed instruments and the training was a struggle.

Playing career

Minor leagues

Stengel signed a contract with the Kansas City Blues of the Class AAA American Association, considered the best minor league, in 1910. He struggled as a pitcher, leading manager Danny Shay to play Stengel as an outfielder. Kansas City optioned Stengel to the Kankakee Kays of the Class D Northern Association, a lower-level minor league, to gain experience as an outfielder. He had a .251 batting average with Kankakee when the league folded in July. He spent the remainder of the 1910 season with the Shelbyville Grays / Maysville Rivermen of the Class D Blue Grass League, batting .221.[1][2]

Stengel attended Western Dental College in the offseason, which provided Stengel with enough negotiating leverage to receive a raise from Kansas City for the 1911 season. The Blues assigned Stengel to the Aurora Blues of the Class C Wisconsin–Illinois League. He led the league with a .351 batting average.[1]

Brooklyn Dodgers' scout Larry Sutton noticed Stengel, and the Dodgers signed Stengel in 1911. They assigned Stengel to the Montgomery Rebels of the Class A Southern Association for the 1912 season. Playing for manager Kid Elberfeld, Stengel batted .290 and led the league in outfield assists. He also developed a reputation as an eccentric player. Scout Mike Kahoe referred to Stengel as a "dandy ballplayer, but it's all from the neck down."[1]

Major League Baseball career

The Dodgers promoted Stengel to the major leagues after the Southern Association season concluded, and he made his MLB debut on September 17, 1912, as their starting center fielder.[1] Stengel played for the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1912 through 1917. Stengel routinely held out from the team before each season in contract disputes. Tired of these disputes, Dodgers' owner Charles Ebbets traded Stengel and George Cutshaw to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Burleigh Grimes, Al Mamaux, and Chuck Ward before the 1918 season.[1]

_(LOC).jpg)

In 1919, Stengel of the Pittsburgh Pirates was being taunted mercilessly by fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers, his old team. Somehow Casey got hold of a sparrow and used it to turn the crowd in his favor. With the bird tucked gently beneath his cap, Casey strutted to the plate amidst a chorus of boos and catcalls. He turned to the crowd, tipped his hat and out flew the sparrow. The jeers turned to cheers, and Stengel became an instant favorite.[1][3][4]

On August 9, 1919, the Pirates traded Stengel to the Philadelphia Phillies for Possum Whitted.[1] On July 1, 1921, the Phillies traded Stengel and Johnny Rawlings to the New York Giants for Lee King, Goldie Rapp, and Lance Richbourg.

He threw left-handed and batted left-handed. His batting average was .284 over 14 major league seasons. He played in three World Series: in 1916 for the Dodgers and in 1922 and 1923 for the Giants.

He was a competent player, but by no means a superstar. On July 8, 1958, discussing his career before the United States Senate's Estes Kefauver committee on baseball's antitrust status, he made this observation: "I had many years that I was not so successful as a ballplayer, as it is a game of skill."[5]

Nonetheless he had a good World Series in a losing cause in 1923, hitting two home runs (one of which was the first World Series home run in old Yankee Stadium) to win the two games the Giants won in that Series. He was traded to the perennial second-division-dwelling Boston Braves during the offseason with Dave Bancroft and Bill Cunningham for Joe Oeschger and Billy Southworth after the 1924 season.[6] This trade apparently stung him. Years later he made the pithy comment "It's lucky I didn't hit three home runs in three games, or [John] McGraw would have traded me to the Three-I League."

Managerial career

In 1914 Stengel got in touch with his baseball and football coach from Kansas City, William L. Driver, who was the football, basketball and baseball coach at the University of Mississippi. Stengel worked as an assistant to Driver for two months before leaving for spring training in Augusta, Georgia. The Ole Miss baseball team finished the season with a 13–9 record. After getting to the Brooklyn spring camp Stengel regaled his teammates about his time at Ole Miss thereby earning the nickname "Professor" which later became "The Old Perfessor".

Stengel's first managerial position came in 1925, as player-manager of the Worcester Panthers of the Eastern League. He also served as team president. For the 1926 season, the Panthers were slated to move to Providence, Rhode Island. However, McGraw, with whom Stengel had remained close over the years, wanted Stengel to take over as manager of their top affiliate, the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association. He was still under contract to Boston, however. To solve this problem, Stengel fired himself as manager, released himself as a player and resigned as president. Braves owner Emil Fuchs briefly protested, but relented and let Stengel move to Toledo. In his second year, Stengel led a roster loaded with former major-leaguers to Toledo's first-ever pennant. His tenure was short-lived, however; the Mud Hens went bankrupt in 1931 and Stengel was out of a job. He then returned to the Dodgers as a coach under one of his former Pirate teammates, Max Carey. When Carey was fired shortly before the 1934 season, Stengel was named his successor.

As manager of the Dodgers (1934–1936) and Boston Braves (1938–1943), Stengel never finished better than fifth in an eight-team league. As he said in 1958, "I became a major league manager in several cities and was discharged. We call it discharged because there is no question I had to leave."[5]

Stengel demonstrated he could be successful as a manager of a team having worthy talent. In 1944, Stengel was hired as the manager of the minor league Milwaukee Brewers, over the strenuous objections of club owner Bill Veeck (who was serving in the South Pacific in the Marines at the time, and therefore unable to prevent the hiring). Stengel led the Brewers to the American Association pennant that year. In 1948 Stengel managed the Oakland Oaks to the Pacific Coast League championship.

New York Yankees

Stengel's success in Oakland caught the attention of the New York Yankees, who were looking for a new manager. Shortly after the PCL season, Stengel was hired as manager of the Yankees for 1949 by George Weiss, an old friend of Stengel's.[7] Upon taking over, Stengel realized he finally had a chance for success at the major league level. He made this observation about his new squad: "There is less wrong with this team than any team I have ever managed."

There was considerable skepticism about Stengel's hiring at first, given his poor record during his earlier stints in Brooklyn and Boston. However, he and the Yankees proceeded to win record numbers of championships. Stengel became the only man to manage a team to five consecutive World Series championships (1949–1953). After the streak ended with the Yankees failing to win the American League pennant in 1954, Stengel and the Yanks continued their dominance, going on to win two more World Championships (1956 and 1958), and five more American League pennants (1955–1958, 1960). As manager of the Yankees, Stengel gained a reputation as one of the game's sharpest tacticians: he platooned left and right-handed hitters extensively (which had become a lost art by the late 1940s),[8] was keen to bring in situational pitchers as evidenced in Game 7 of the 1952 World Series with Bob Kuzava to retire the Dodgers with bases loaded in the 7th, and sometimes pinch hit for his starting pitcher in early innings if he felt a timely hit would break the game open.[1]

In the spring of 1953, after the Yankees had won four straight World Series victories, he made the following observation, which could just as easily have been made by The Professor's prize pupil, Yogi Berra (who would also become famous with many laughably quotable statements): "If we're going to win the pennant, we've got to start thinking we're not as smart as we think we are."[9]

"I never saw a man who juggled his lineup so much and who played so many hunches so successfully."

Although Stengel benefited from the Yankees' deep pockets and ability to sign players, he was a hands-on manager: The 1949 Yankees were riddled by injuries, and Stengel's platooning abilities played a major role in their championship run. Platooning also played a major role in the 1951 team's World Series run. With Joe DiMaggio declining rapidly and Mickey Mantle yet to become a powerhouse, Stengel, leaving his solid pitching alone, moved players in and out of the line-up, putting good hitters in the line-up in the early innings and benching them for superior fielders later. The Yankees beat the Cleveland Indians for the pennant and took the Series from the New York Giants four games to two.[10]

After 1953, the Yankees' rate of success started dropping. The team continued their total domination of the AL and in 1960 achieved their tenth pennant in eleven seasons, but won the World Series only two more times, in 1956 and 1958, in spite of all-star talent such as Yogi Berra and Mickey Mantle. During the late '50s, Stengel increasingly began to quarrel with players and management. He was widely accused of being too old for the job and being unable to connect with his players, in particular Mickey Mantle, who showed very little regard for Stengel.

At the start of the 1960 season, Stengel was hospitalized after suffering chest pains. He agreed to give up alcohol consumption for a few months and in one of his famous quips, told reporters "They examined all my organs. Some of them are quite remarkable and others are not so good. A lot of museums are bidding for them." In the 1960 World Series, the Yankees were downed by Pittsburgh after a ninth-inning game-winning home run by Bill Mazeroski. Stengel was fired immediately afterwards, with no particular reason given other than that the team needed a "change in direction". As reported in Ken Burns' PBS documentary series, Baseball, Stengel remarked that he had been fired for turning 70, and that he would "never make that mistake again." In his 1962 autobiography, Stengel wrote that he'd gotten the sense he would have been forced out even if the Yankees had won the World Series. John Rosenberg's book, Baseball (1963), described the press conference where Casey announced that his "services were no longer desired." Reporters implored him to say whether he was fired: "I was told my services were no longer desired. That was their excuse; the best they've got."

New York Mets

Stengel was talked out of retirement after one season to manage the New York Mets, at the time an expansion team with no chance of winning many games. Mocking his well-publicized advanced age, when he was hired he said, "It's a great honor to be joining the Knickerbockers", a New York baseball team that had seen its last game around the time of the Civil War.[11]

The lack of success for the Mets led Stengel to make many sarcastic comments to New York City newspaper writers. "Come see my "Amazin' Mets", Stengel said. "I've been in this game a hundred years, but I see new ways to lose I never knew existed before." On his three catchers: "I got one that can throw but can't catch, one that can catch but can't throw, and one who can hit but can't do either." Referring to the rookies Ed Kranepool and Greg Goossen in 1965, Stengel observed, "See that fellow over there? He's 20 years old. In 10 years he has a chance to be a star. Now, that fellow over there, he's 20, too. In 10 years he has a chance to be 30." Kranepool never quite became a star, but he did have an 18-year major league career, retiring in 1979 after playing his entire career with the Mets and becoming their all-time hits leader, before it was broken by David Wright in 2012. Goossen left the majors 5 years before his 30th birthday.

One of his most famous comments was actually the work of Jimmy Breslin, who used it as the title of his book about the first-year Mets, Can't Anybody Here Play This Game?.[12]

Though his "Amazin'" Mets finished last in a ten-team league all four years managed by him, Stengel was a popular figure with reporters nonetheless, partially due to his personal charisma. The Mets themselves somehow attained a "lovable loser" charm that followed the team around in those days. Fans packed the old Polo Grounds (prior to Shea Stadium being built), many of them bringing along colorful placards and signs with all sorts of sayings on them. Warren Spahn, who had briefly played under Stengel for the 1942 Braves and for the 1965 Mets, commented: "I'm probably the only guy who worked for Stengel before and after he was a genius."[13]

In the spring of 1965, although a few months from turning 75, Stengel showed no apparent desire to quit as he signed a contract extension with the team. He broke his wrist after slipping on wet pavement during spring training, but continued to manage the team with his arm in a sling and with increased calls from the sports media and some players to retire.

On July 24, 1965, while attending a party at Toots Shor's restaurant in Manhattan, Stengel fell off a bar stool. Apparently unscathed, he then traveled to a friend's home in Queens and broke his hip while stepping out of a car. He was hospitalized and fitted for an artificial hip, and on August 30, announced his retirement from baseball.[14]

Managerial record

| Team | From | To | Regular season record | Post–season record | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | L | Win % | W | L | Win % | ||||

| Brooklyn Dodgers | 1934 | 1936 | 208 | 251 | .453 | — | [15] | ||

| Boston Braves | 1938 | 1942 | 326 | 431 | .431 | [15] | |||

| Boston Braves | 1943 | 1943 | 47 | 60 | .439 | [15] | |||

| New York Yankees | 1949 | 1960 | 1149 | 696 | .623 | 37 | 26 | .587 | [15] |

| New York Mets | 1962 | 1965 | 175 | 404 | .302 | — | [15] | ||

| Total | 1905 | 1842 | .508 | 37 | 26 | .587 | — | ||

Awards and honors

| |

| Casey Stengel's number 37 was retired by the New York Yankees in 1970. |

| |

| Casey Stengel's number 37 was retired by the New York Mets in 1965. |

Stengel had his uniform number, 37, retired by both the Yankees and the Mets. He is the first man in MLB history to have had his number retired by more than one team based solely upon his managerial accomplishments (Sparky Anderson became the second in 2011). Anderson referred to Stengel as "the greatest man" in the history of baseball.[16] 37 is the only number ever to have been issued only once by the Mets. The Yankees retired the number on August 8, 1970, and dedicated a plaque in Yankee Stadium's Monument Park in his memory on July 30, 1976. The plaque reads "Brightened baseball for over 50 years; with spirit of eternal youth; Yankee manager 1949 – 1960 winning 10 pennants and 7 world championships including a record 5 consecutive, 1949 – 1953." In addition to his election to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966,[17] he was inducted into the New York Mets Hall of Fame in 1981.

Stengel was the first man to have worn the uniform (as player or manager) of all four Major League Baseball teams in New York City in the 20th century: the New York Giants (as a player), the Brooklyn Dodgers (as both a player and a manager), the New York Yankees (as a manager), and the New York Mets (also as a manager). In addition, he is the only person to have played or managed for the home team in five New York City major league venues: Washington Park, Ebbets Field, Polo Grounds, Shea Stadium, and Yankee Stadium. As he often said, "You can look it up." In 2009, in an awards segment on the MLB Network titled "The Prime 9", he was named "The Greatest Character of The Game." He received this award not only for his colorful personality and antics on the field, but also his off-field contributions to the community.

Personality

Stengel was always friendly to the media and photographers who were willing to take a picture of him.[18] Stengel was a master publicist and promoter, especially for his teams. He became as much of a public figure as many of his star players, such as Mickey Mantle. He appeared on the cover of national, non-sports, magazines such as Time. His apparently stream-of-consciousness monologues on all facets of baseball history and tactics became known as "Stengelese" to sportswriters. They also earned him the nickname "The Old Professor".

According to Dave Egan of the The Boston Record, Stengel was a "funny guy at somebody else's expense".[19] He was considered cruel, in his own way, to his players, and some of his players, most notably Joe DiMaggio, hated his personality.[19] DiMaggio called Stengel the most "bewildered guy" he ever met.[20] Zack Wheat once said of Stengel: "There was never a day around Casey that I didn't laugh".[21]

Accusations of racism

Stengel ran afoul of longtime Dodgers foe Jackie Robinson, who claimed that he was a racist and that the Yankees did not sign an African-American player until eight years after he broke the color barrier in 1947. Robinson also claimed that he frequently slept through games. The first African-American to wear a Yankees uniform, left fielder Elston Howard, never recalled Stengel displaying any prejudice other than use of racial epitaphs which were commonplace in that era. By all accounts, Stengel had nothing but good things to say about African-American players such as Satchel Paige and Elston Howard.[22]

Managing style

Stengel was considered to have a "prodigious memory", remembering every relevant detail of an event.[23] His managing style was described as "intuitive", which according to Creamer was likely derived from Stengel's long experience in the game.[24] His American League rival Al López, who played for Stengel with the Dodgers and the Braves once said of Stengel "I swear I don't understand some of the things he does when he manages".[24]

Later years and death

Stengel was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame a year after his retirement. He maintained an active schedule despite his advancing age, attending the Hall of Fame ceremony in Cooperstown every year. After the Mets won the 1969 World Series, the team presented Stengel with a championship ring.

Stengel remained in good health past the age of 80, still attending the All Star game and the World Series every year. In 1973, his wife Edna experienced a stroke and was moved into a care facility, but he continued to live in his Glendale home with the help of his housekeeper June Bowdin. Stengel's health finally began to decline in early 1975 and he was admitted to Glendale Memorial Hospital in Glendale, California on September 14, 1975 after not feeling well. It was there that he learned he had cancer of the lymph glands. He died there of cancer 15 days later on September 29, 1975. Stengel was interred in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery, Glendale, California. His wife outlived him by 2-1/2 years and was buried next to him. A plaque at the cemetery reads in part "For over sixty years one of America's folk heroes who contributed immensely to the lore and language of our country's national pastime, baseball".

The Casey Stengel Plaza outside Shea Stadium's Gate E was named after him, as is the New York City Transit's Casey Stengel Depot across the street from Shea Stadium at the time, and now Citi Field.

A sculpture of Casey Stengel is part of the IUPUI Public Art Collection. The sculpture by Rhoda Sherbell can be found outside of courtyard of University Place.

Books

- Casey at the Bat: The Story of My Life in Baseball, by Casey Stengel and Harry T. Paxton, Random House, 1962.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bill Bishop, Casey Stengel

- ↑ "It's a Long Way Back to Kankakee". Toledo Blade. May 11, 1960. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ Cataneo, David (2003). Casey Stengel: Baseball's Old Professor. Cumberland House Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 1-58182-327-4.

- ↑ McGee, Bob (2005). The greatest ballpark ever: Ebbets Field and the story of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rutgers University Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-8135-3600-6.

- 1 2 Einstein, Charles (1968). The Third Fireside Book of Baseball. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 434.

- ↑ "Dave Bancroft to Manage Braves". The Milwaukee Sentinel.

- 1 2 "Casey Stengel Old Perfessor".

- ↑ Loomis, Tom (May 13, 1987). "Don't Blame Casey Stengel For Inventing Platoon System". Toledo Blade. p. 26. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ Ira Berkow and Jim Kaplan. The Gospel According to Casey. New York; St. Martin's Press, 1992, p.120

- ↑ Creamer, Robert W. (1984). Stengel: His Life and Times. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 227–249.

- ↑ Ira Berkow and Jim Kaplan. The Gospel According to Casey. New York; St. Martin's Press, 1992, p.15

- ↑ Ira Berkow and Jim Kaplan. The Gospel According to Casey. New York; St. Martin's Press, 1992, p.21.

- ↑ Ira Berkow and Jim Kaplan. The Gospel According to Casey. New York; St. Martin's Press, 1992, p.x.

- ↑ Ken Burns's Baseball

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Casey Stengel". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ↑ http://articles.latimes.com/1985-08-11/sports/sp-2922_1_casey-stengel

- ↑ "Hall of Fame Welcomes Two More Greats". The Herald Journal. July 26, 1966. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ Creamer, p. 12

- 1 2 Creamer, p. 13

- ↑ Creamer, p. 221

- ↑ Creamer, p. 17.

- ↑ http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bd6a83d8

- ↑ Creamer, p. 14

- 1 2 Creamer, p. 15

Further reading

- Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia, by David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman and Michael Gershman, ed. (2000). Total/Sports Illustrated.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Casey Stengel |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Casey Stengel. |

- Casey Stengel managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Stengel's testimony at Kefauver hearings