Christabel Pankhurst

| Christabel Pankhurst DBE | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Christabel Pankhurst, c. 1910 | |

| Born |

Christabel Harriette Pankhurst 22 September 1880 Old Trafford, Manchester, England |

| Died |

13 February 1958 (aged 77) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Memorial Cemetery |

| Occupation | Political activist |

| Parent(s) |

Richard Pankhurst Emmeline Pankhurst (née Goulden) |

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst, DBE (/ˈpæŋkhərst/; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958), was a suffragette born in Manchester, England. A co-founder of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), she directed its militant actions from exile in France from 1912 to 1913. In 1914 she supported the war against Germany. After the war she moved to the United States, where she worked as an evangelist for the Second Adventist movement.

Early life

Christabel Pankhurst was the daughter of women's suffrage movement leader Emmeline Pankhurst[1] and radical socialist Richard Pankhurst and sister to Sylvia and Adela Pankhurst. Her father was a lawyer and her mother owned a small shop. Christabel assisted her mother, who worked as the Registrar of Births and Deaths in Manchester. Despite financial struggles, her family had always been encouraged by their firm belief in their devotion to causes rather than comforts.

Nancy Ellen Rupprecht wrote, "She was almost a textbook illustration of the first child born to a middle-class family. In childhood as well as adulthood, she was beautiful, intelligent, graceful, confident, charming, and charismatic." Christabel enjoyed a special relationship with both her mother and father, who had named her after "Christabel", the poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge ("The lovely lady Christabel / Whom her father loves so well").[2] Her mother's death in 1928 had a devastating impact on Christabel.[3][4]

Education

Pankhurst learned to read at her home on her own before she went to school. She and her two sisters attended Manchester High School for Girls. She obtained a law degree from the University of Manchester, and received honours on her LL.B. exam but, as a woman, was not allowed to practice law. Later Pankhurst moved to Geneva to live with a family friend, but returned home to help her mother raise the rest of the children, when her father died in 1898.[3]

Activism

Suffrage

In 1905 Christabel Pankhurst interrupted a Liberal Party meeting by shouting demands for voting rights for women. She was arrested and, along with fellow suffragist Annie Kenney,[1] went to prison rather than pay a fine as punishment for their outburst. Their case gained much media interest and the ranks of the WSPU swelled following their trial. Emmeline Pankhurst began to take more militant action for the women's suffrage cause after her daughter's arrest and was herself imprisoned on many occasions for her principles.

After obtaining her law degree in 1906, Christabel moved to the London headquarters of the WSPU, where she was appointed its organising secretary. Nicknamed "Queen of the Mob", she was jailed again in 1907 in Parliament Square and in 1909 after the "Rush Trial" at Bow Street. Between 1913 and 1914 she lived in Paris, France, to escape imprisonment under the terms of the Prisoner's (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, better known as the "Cat and Mouse Act". The start of World War I compelled her to return to England in 1914, where she was again arrested. Pankhurst engaged in a hunger strike, ultimately serving only 30 days of a three-year sentence.

She was influential in the WSPU's "anti-male" phase after the failure of the Conciliation Bills. She wrote a book called The Great Scourge and How to End It on the subject of sexually transmitted diseases and how sexual equality (votes for women) would help the fight against these diseases.[5]

She and her sister Sylvia did not get along. Sylvia was against turning the WSPU towards solely upper- and middle-class women and using militant tactics, while Christabel thought it was essential. Christabel felt that suffrage was a cause that should not be tied to any causes trying to help working-class women with their other issues. She felt that it would only drag the suffrage movement down and that all of the other issues could be solved once women had the right to vote.[3]

White feathers

On 8 September 1914, Pankhurst re-appeared at the London Opera House, after her long exile, to utter a declaration on "The German Peril", a campaign led by the former General Secretary of the WSPU, Norah Dacre Fox in conjunction with the British Empire Union and the National Party.[6] Along with Norah Dacre Fox (later known as Norah Elam), Pankhurst toured the country making recruiting speeches. Her supporters handed the white feather to every young man they encountered wearing civilian dress. The Suffragette appeared again on 16 April 1915 as a war paper and on 15 October changed its name to Britannia. In its pages, week by week, Pankhurst called for the military conscription of men and the industrial conscription of women into national service. She called also for the internment of all people of enemy nationality, men and women, young and old, found on these shores. Her supporters bobbed up at Hyde Park meetings with placards: "Intern Them All". She also championed a more complete and thorough enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral nations, arguing that this must be "a war of attrition". She demanded the resignation of Sir Edward Grey, Lord Robert Cecil, General Sir William Robertson and Sir Eyre Crowe, whom she considered too mild and dilatory in method. Britannia was many times raided by the police and experienced greater difficulty in appearing than had befallen The Suffragette. Indeed, although occasionally Norah Dacre Fox's father, John Doherty, who owned a printing firm, was drafted in to print campaign posters,[6] Britannia was compelled at last to set up its own printing press. Emmeline Pankhurst proposed to set up Women's Social and Political Union Homes for illegitimate girl "war babies", but only five children were adopted. David Lloyd George, whom Pankhurst had regarded as the most bitter and dangerous enemy of women, was now the one politician in whom she and Emmeline Pankhurst placed confidence.

After some British women were granted the right to vote at the end of World War I, Pankhurst stood in the 1918 general election as a Women's Party candidate, in alliance with the Lloyd George/Conservative Coalition in the Smethwick constituency. She was narrowly defeated, by only 775 votes to the Labour Party candidate John Davison.

Move to California

Leaving England in 1921, she moved to the United States where she eventually became an evangelist with Plymouth Brethren links and became a prominent member of Second Adventist movement. Marshall, Morgan, and Scott published her works on subjects related to her prophetic outlook, which took its character from John Nelson Darby's perspectives. Pankhurst lectured and wrote books on the Second Coming. She was a frequent guest on TV shows in the 1950s and had a reputation for being an odd combination of "former suffragist revolutionary, evangelical Christian and almost stereotypically proper 'English Lady' who always was in demand as a lecturer". While in California, she adopted her daughter Betty, finally having recovered from her mother's death.

She returned to Britain for a period in the 1930s and was appointed a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1936.[1] At the onset of World War II she again left for the United States, to live in Los Angeles, California.

Death

Christabel died 13 February 1958, at the age of 77, sitting in a straight-backed chair. Her housekeeper found her body and there was no indication of her cause of death. She was buried in the Woodlawn Memorial Cemetery in Santa Monica, California.[3]

Popular culture

Christabel Pankhurst was portrayed by actress Patricia Quinn in the 1974 BBC Television serial Shoulder to Shoulder and is depicted in the graphic novel trilogy Suffrajitsu: Mrs. Pankhurst's Amazons (2015).

See also

- History of feminism

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Pankhurst Centre in Manchester

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom

- Women's suffrage organisations

References

- 1 2 3 Christabel Panhurst, Britannica.com, Retrieved 21 September 2016

- ↑ Fulford, Roger. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Hillberg, Isabelle. "Pankhurst, Christabel Hariette (1880–1958)". Detroit:Gale. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ↑ "Christabel Pankhurst". Gale. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Pankhurst C, 1913. The Great Scourge and How to End It Archived 3 March 2001 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 McPherson, Angela; McPherson, Susan (2011). Mosley's Old Suffragette – A Biography of Norah Elam. ISBN 978-1-4466-9967-6.

Further reading

- Christabel Pankhurst, Pressing Problems of the Closing Age (Morgan & Scott Ltd., 1924).

- Christabel Pankhurst, The World's Unrest: Visions of the Dawn (Morgan & Scott Ltd., 1926).

- David Mitchell, Queen Christabel (MacDonald and Jane's Publisher Ltd., 1977) ISBN 0-354-04152-5

- Barbara Castle, Sylvia and Christabel Pankhurst (Penguin Books, 1987) ISBN 978-0-14-008761-1.

- Timothy Larsen, Christabel Pankhurst: Fundamentalism and Feminism in Coalition (Boydell Press, 2002).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christabel Pankhurst. |

- Works by or about Christabel Pankhurst at Internet Archive

- 1908 audio recording of Christabel Pankhurst speaking

- http://www.spartacus-educational.com/WpankhurstC.htm

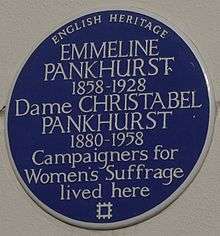

- Blue Plaque for Suffragette Leaders Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst

- "Christabel Harriette Pankhurst". Suffragette. Find a Grave. 9 June 2005. Retrieved 18 August 2011.