Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon

| The Right Honourable The Viscount Grey of Fallodon KG PC DL FZS | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |

|

In office 10 December 1905 – 10 December 1916 | |

| Prime Minister |

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Lansdowne |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Balfour |

| British Ambassador to the United States | |

|

In office 1919–1920 | |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Reading |

| Succeeded by | Sir Auckland Geddes |

| Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |

|

In office 18 August 1892 – 20 June 1895 | |

| Prime Minister |

William Ewart Gladstone The Earl of Rosebery |

| Preceded by | James Lowther |

| Succeeded by | Hon. George Curzon |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

25 April 1862 London, England, UK |

| Died |

7 September 1933 (aged 71) Fallodon, Northumberland, England, UK |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse(s) | (1) Dorothy Widdrington (20 October 1885 – 4 February 1906) (2) Pamela Wyndham (d. 18 November 1928) |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Profession | Politician |

| Religion | Anglican |

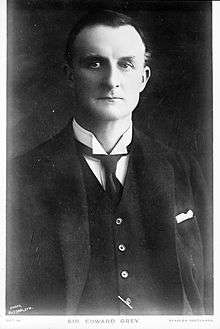

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, KG, PC, DL, FZS (25 April 1862 – 7 September 1933), better known as Sir Edward Grey (he was 3rd Baronet Grey of Fallodon), was a British Liberal statesman. An adherent of the "New Liberalism",[1] he served as Foreign Secretary from 1905 to 1916, the longest continuous tenure of any person in that office. He is probably best remembered for his "the lamps are going out" remark on 3 August 1914 on the outbreak of the First World War.[2] He signed the Sykes-Picot Agreement on 16 May 1916.[3] Ennobled in 1916, he was Ambassador to the United States between 1919 and 1920 and Leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords between 1923 and 1924.

Background, education and early life

Grey was the eldest of the seven children of Colonel George Henry Grey and Harriet Jane Pearson, daughter of Charles Pearson. His grandfather Sir George Grey, 2nd Baronet of Fallodon, was also a prominent Liberal politician, while his great-grandfather Sir George Grey, 1st Baronet of Fallodon, was the third son of Charles Grey, 1st Earl Grey, and the younger brother of Prime Minister Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey.[4] He was also a cousin of two later British Foreign Secretaries: Anthony Eden and Lord Halifax. Grey attended Temple Grove School from 1873 until 1876. Whilst he was at that school his father died unexpectedly in December 1874, and his grandfather assumed responsibility for his education, sending him to Winchester College.[5]

Grey went on to Balliol College, Oxford, in 1880 to read Literae Humaniores. Apparently an indolent student, he was tutored by Mandell Creighton during the vacations and managed a second class honours degree in Honour Moderations. Grey subsequently became even more idle, using his time to become university champion at real tennis. In 1882 his grandfather died and he inherited a baronet's title, an estate of about 2,000 acres (8.1 km2), and a private income. Returning to the University of Oxford in the autumn of 1883, Grey switched to studying jurisprudence (law) in the belief that it would be an easier option, but by January 1884 he had been expelled. Nonetheless, he was allowed to return to sit his final examination. Grey returned in the summer and achieved Third Class honours.

Grey left university with no clear career plan and in the summer of 1884 he asked a neighbour, Lord Northbrook, at the time First Lord of the Admiralty, to find him "serious and unpaid employment." Northbrook recommended him as a private secretary to his kinsman Sir Evelyn Baring, the British consul general to Egypt, who was attending a conference in London. Grey had shown no particular interest in politics whilst at university, but by the summer of 1884 Northbrook found him "very keen on politics," and after the Egyptian conference had ended found him a position as an unpaid assistant private secretary to Hugh Childers, the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Early political career

Grey was selected as the Liberal Party candidate for Berwick-upon-Tweed where his Conservative opponent was Earl Percy. He was duly elected in November 1885 and, at 23, became the youngest MP (Baby of the House) in the new House of Commons. He was not called in the Home Rule debate, but was nonetheless convinced by Gladstone and Morley of the rightness of the cause. A year later Grey summoned up the courage to make a maiden speech, at a similar period to Asquith. During the debate over the 1888 Land Purchase Bill he began "an association and friendship" with Haldane, which was "thus strengthened as years went on". The nascent imperialists voted against "this passing exception".[6] On a previous occasion he had met Neville Lyttelton, later a knight and general, who would become his closest friend.[7]

Grey retained his seat in the 1892 election with a majority of 442 votes and to his surprise was made Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs by William Ewart Gladstone (albeit after his son Herbert had refused the post) under the Foreign Secretary, Lord Rosebery. Grey would later claim that at this point he had had no special training nor paid special attention to foreign affairs.[8] The new Under-Secretary prepared the policy for making Uganda a new colony, proposing to build a railway from Cairo through East Africa. There was continuity in presentation and preparation during the Scramble for Africa; foreign policy was not an election issue. The Liberals continued to incline towards the Triple Alliance, causing the press to write of a "Quadruple Alliance".

Grey later dated his first suspicions of future Anglo-German disagreements to his early days in office, after Germany had sought commercial concessions from Britain in the Ottoman Empire; in return they would promise support for a British position in Egypt. "It was the abrupt and rough peremptoriness of the German action that gave me an unpleasant impression"; not, he added, that the German position was at all "unreasonable," rather that the "method... was not that of a friend."[9] With hindsight, he argued in his autobiography, "the whole policy of the years from 1886 to 1904 [might] be criticized as having played into the hands of Germany."[10]

1895 statement on French expansion in Africa

Prior to the Foreign Office vote on 28 March 1895, Grey asked Lord Kimberley, the new Foreign Secretary, for direction as to how he should answer any question about French activities in West Africa. According to Grey, Kimberley suggested "pretty firm language."[11] In fact, West Africa was not mentioned, but when pressed on possible French activities in the Nile Valley Grey stated that a French expedition "would be an unfriendly act and would be so viewed by England."[12] According to Grey the subsequent row both in Paris and in the Cabinet was made worse by the failure of Hansard to record that his statement referred explicitly to the Nile Valley and not to Africa in general.[13] The statement was made before the dispatch of the Marchand expedition—indeed, he believed it might have actually provoked it—and as Grey admits did much to damage future Anglo-French relations.[14]

The Liberal Party lost a key vote in the House of Commons on 21 June 1895, and Grey was among the majority in his party that preferred a dissolution to continuing. He seems to have left office with few regrets, noting, "I shall never be in office again and the days of my stay in the House of Commons are probably numbered. We [he and his wife] are both very glad and relieved...."[15] The Liberals were soundly defeated in the subsequent General Election, although Grey added 300 votes to his own majority.[16] He was to remain out of office for the next ten years, but was sworn of the Privy Council in 1902.[17] He was appointed a deputy lieutenant of Northumberland in 1901.[18]

Foreign Secretary 1905–1916

With the Conservative government of Arthur Balfour divided and unpopular, there was some speculation that H. H. Asquith and his allies Grey and Richard Haldane would refuse to serve in the next Liberal government unless the Liberal leader Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman accepted a peerage, which would have left Asquith as the real leader in the House of Commons. The plot (called the "Relugas Compact" after the Scottish lodge where the men met) collapsed when Asquith agreed to serve as Chancellor of the Exchequer under Campbell-Bannerman. When Campbell-Bannerman formed a government in December 1905 Grey was appointed Foreign Secretary—the first Foreign Secretary to sit in the Commons since 1868. Haldane became Secretary of State for War. The party won a landslide victory in the 1906 general election. Whilst an MP he voted in favour of the 1908 Women's Enfranchisement Bill.[19] When Campbell-Bannerman stepped down as Prime Minister in 1908, Grey was Asquith's only realistic rival to succeed his friend. In the event, Grey continued as Foreign Secretary, and held office for 11 years to the day, the longest continuous tenure in that office.

Anglo-Russian Entente 1907

As early as 13 December 1905, Grey had assured the Russian Ambassador Count Alexander Benckendorff that he supported the idea of an agreement with Russia.[20] Negotiations began soon after the arrival of Sir Arthur Nicolson as the new British Ambassador in June 1906. In contrast with the previous Conservative government that had seen Russia as a potential threat to the empire, Grey's intention was to re-establish Russia "as a factor in European politics"[21] on the side of France and Great Britain to maintain a balance of power in Europe.[22]

Agadir Crisis 1911

Grey did not welcome the prospect of a renewed crisis over Morocco: he worried that it might either lead to a re-opening of the issues covered by the Treaty of Algeciras or that it might drive Spain into alliance with Germany. Initially Grey tried to restrain both France and Spain, but by the spring of 1911 he had failed on both counts. Grey believed that, whether he liked it or not, his hands were tied by the terms of the Entente cordiale. The despatch of the German gunboat Panther to Agadir served to strengthen French resolve and, because he was determined both to protect the agreement with France and also to block German attempts at expansion around the Mediterranean, it pushed Grey closer to France. Grey, however, tried to calm the situation, merely commenting on the "abrupt" nature of the German intervention, and insisting that Britain must participate in any discussions about the future of Morocco.

In cabinet on 4 July, Grey accepted that the UK would oppose any German port in the region, any new fortified port anywhere on the Moroccan coast, and that Britain must continue to enjoy an "open door" for its trade with Morocco. Grey at this point was resisting efforts by the Foreign Office to support French intransigence. By the time a second cabinet was held on 21 July, Grey had adopted a tougher position, suggesting that he propose to Germany that a multi-national conference be held, and that were Germany to refuse to participate "we should take steps to assert and protect British interests."[23]

Grey was made a Knight of the Garter in 1912.[24] Throughout the period leading up to World War Grey played a leading part in negotiations with the Kaiser. He visited Germany and invited their delegation to the Windsor Castle Conference in 1912. They returned several times, with Haldane acting as interpreter.

July Crisis 1914

Although Grey's activist foreign policy, which relied increasingly on the Triple Entente with France and Russia, came under criticism from the radicals within his own party, he maintained his position because of support from the Conservatives for his "non-partisan" foreign policy. In 1914, Grey played a key role in the July Crisis leading to the outbreak of World War I. His attempts to mediate the dispute between Austria-Hungary and Serbia came to nothing. On 16 July, British ambassador to Austria-Hungary advised the British Foreign Secretary that Austria-Hungary regarded the Serbian government as having been complicit in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, and would have to act if Austria-Hungary was not to lose her position as a Great Power. Grey failed to realize the urgency of the situation, and chose to await further developments. On 23 July, Austria-Hungary formally handed the Serbian government a much-discussed Ultimatum, which demanded their acceptance, by 25 July, of terms tantamount to Serbia’s vassalage to Austria-Hungary. On 24 July, the French ambassador in London tried to waken Grey to the realization that once Austrian forces crossed the Serbian border, it would be too late for mediation. Grey responded by urging the German ambassador to attempt a four-power (Germany, Great Britain, France and Italy) mediation at Vienna to obtain at least an extension of the time-limit set by Austria-Hungary. When this failed, he suggested that Russia and Austria-Hungary should be encouraged to negotiate. Germany had other intentions.

At a meeting with Prince Lichnowsky, the German Ambassador, early on 1 August, Grey stated the conditions necessary for Britain to remain neutral, but perhaps with a lack of clarity. Grey did not make it clear that Britain would not ignore a breach of the Treaty of London (1839), to respect and protect the neutrality of Belgium. Nor it seems did he make it clear that Britain would support Russia, for at 11:14 AM that morning, the German Ambassador sent a telegram to Berlin which indicated that Grey had proposed that, if Germany were not to attack France, Britain would remain neutral.[25] King George telegraphed Berlin to confirm that Grey had stated that Britain would remain neutral if France and Russia were not attacked. By 31 July, when Grey finally sent a memorandum demanding that Germany respect Belgium's neutrality, it was too late. German forces were already massed at the Belgian border, and Helmuth von Moltke convinced Kaiser Wilhelm II it was too late to change the plan of attack. On 3 August, Germany declared war on France and broke the treaty by invading Belgium. As Grey stood at a window in the Foreign Office, watching the lamps being lit as dusk approached, he is famously said to have remarked to the editor of the Westminster Gazette, "The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our time."[26] The British Cabinet voted almost unanimously to declare war on 4 August.

First World War

After the outbreak of World War I, the conduct of British foreign policy was increasingly constrained by the demands of a military struggle beyond Grey's control. During the war, Grey worked with Marquess of Crewe to press an initially reluctant ambassador to the United States, Sir Cecil Spring Rice, to raise the issue of the Hindu-German Conspiracy with the American government; this ultimately led to the unfolding of the entire plot.

In the early years of the war, Grey oversaw negotiation of important secret agreements with new allies (Italy and the Arab rebels) and with France and Russia (the Sykes-Picot Agreement which, among other provisions, assigned control of the Turkish Straits to Russia if the Triple Entente powers defeated the Ottoman Empire). Otherwise, Asquith and Grey generally preferred to avoid discussion of war aims for fear of raising an issue that might fracture the Entente. In a 12 February 1916 paper the new Chief of the Imperial General Staff William Robertson proposed that the Allies offer a separate peace to Turkey, or offer Turkish territory to Bulgaria to encourage Bulgaria to break with the Central Powers and make peace, so as to allow British forces in that theatre to be redeployed against Germany. Grey replied that Britain needed her continental allies more than they needed her, and imperial interests could not incur the risk (e.g., by reneging on the promise that Russia was to have control of the Turkish Straits) that they might choose to make a separate peace, which would leave Germany dominant on the continent.[27]

Grey retained his position as Foreign Secretary when Asquith's Coalition Government (which included the Conservatives) was formed in May 1915. Grey was one of those Liberal ministers who contemplated joining Sir John Simon (Home Secretary) in resigning in protest at the conscription of bachelors, due to be enacted in January 1916, but he did not do so.[28]

In an attempt to reduce his workload, he left the House of Commons for the House of Lords in July 1916, accepting a peerage as Viscount Grey of Fallodon, in the County of Northumberland.[29] When Asquith's ministry collapsed in December 1916 and David Lloyd George became Prime Minister, Grey went into opposition.

Later career

In 1919 Grey was appointed Ambassador to the United States,[30] a post he held until 1920.

By mid July 1920 Lord Robert Cecil, a moderate and staunchly pro-League of Nations Conservative, was keen for a party realignment under Grey, who was also a strong supporter of the League.[31]

Grey had been cross at Asquith’s failure to congratulate him when sent to Washington in 1919, but they reestablished relations in November 1920.[32] Asquith reached an agreement with Grey on 29 June 1921, suggesting that he could be Leader in the Lords and Lord President of the Council in any future Liberal Government, as his eyesight was no longer good enough to cope with the paperwork of running a major department. Grey wanted British troops simply pulled out of Ireland and the Irish left to sort themselves out, a solution likened by Roy Jenkins to the British withdrawal from India in 1947.[33]

The success of Anti-Waste League candidates at by-elections made leading Liberals feel that there was a strong vote which might be tapped by a wider-based and more credible opposition to Lloyd George's Coalition government.[34] Talks between Grey and Lord Robert Cecil also began in June 1921.[35] A wider meeting (Cecil, Asquith, Grey, and leading Liberals Lord Crewe, Walter Runciman and Sir Donald Maclean) was held on 5 July 1921. Cecil wanted a genuine coalition rather than a de facto Liberal government, with Grey rather than Asquith as Prime Minister, and an official manifesto by himself and Grey which the official Liberal leaders Asquith and Lord Crewe would then endorse. Another Conservative, Sir Arthur Steel-Maitland, later joined in the talks, and his views were similar to Cecil’s, but Maclean, Runciman and Crewe were hostile. Grey himself was not keen, and his eyesight would have been a major handicap to his becoming Prime Minister. He missed the third meeting, saying that he was feeding squirrels in Northumberland, and was late for the fourth. He did, however, make a move by speaking in his former constituency in October 1921, to little effect, after which the move for a party realignment fizzled out.[36]

Grey continued to be active in politics despite his near blindness, serving as Leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords from 1923 until his resignation on the grounds that he was unable to attend on a regular basis shortly before the 1924 election. Having declined to stand for Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 1925, to make way for Asquith's unsuccessful bid, he was elected unopposed as in 1928 and held the position until his death in 1933.[37]

Private life

Grey married Dorothy, daughter of S. F. Widdrington, of Newton Hall, Northumberland, in 1885. After her death in February 1906 he married Pamela Adelaide Genevieve, daughter of the Honourable Percy Wyndham and widow of Lord Glenconner, in 1922. There were no children from either marriage.[4] According to Max Hastings, however, Grey had two illegitimate children as a result of extra-marital affairs.[38]

During his university years Grey represented his college at football and was also an excellent tennis player being Oxford champion in 1883 (and winning the varsity competition the same year) and won the British championship in 1889, 1891, 1895, 1896 and 1898. He was runner-up in 1892, 1893 and 1894, years in which he held office.[39] He was also a lifelong fly fisherman, publishing a book, Fly Fishing, on his exploits in 1899,[40] which remains one of the most popular books ever written on the subject. He continued to fish by touch after his deteriorating eye-sight meant he was no longer able to see the fly or a rising fish. He was also an avid ornithologist; one of the best-known photographs of him shows him with a robin perched on his hat; The Charm of Birds was published in 1927. He was among his Liberal friends Asquith and Haldane, a member of the Coefficients dining club of social reformers set up in 1902 by the Fabian campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb.

Lady Grey of Fallodon died on 18 November 1928. Lord Grey remained a widower until his death at Fallodon on 7 September 1933, aged 71, following which he was cremated at Darlington.[41] The Viscountcy became extinct on his death, though he was succeeded in the baronetcy by his cousin, Sir George Grey.[4]

Styles of address

- 1862-1882: Mr Edward Grey

- 1882-1885: Sir Edward Grey Bt

- 1885-1901: Sir Edward Grey Bt MP

- 1901-1902: Sir Edward Grey Bt DL MP

- 1902-1912: The Right Honourable Sir Edward Grey Bt DL MP

- 1912-1916: The Right Honourable Sir Edward Grey Bt KG DL MP

- 1916-1933: The Right Honourable The Viscount Grey of Fallodon KG PC DL[lower-alpha 1]

- ↑ Although The Viscount Grey of Fallodon was a baronet, by custom the post-nominal of "Bt" is omitted, as Peers of the Realm do not list subsidiary hereditary titles.

Works

- Cottage Book. Itchen Abbas, 1894–1905 (1909)

- Recreation (1920)

- Twenty-Five Years, 1892–1916 (1925)

- Fallodon Papers (1926)

- The Charm of Birds (Hodder and Stoughton, 1927)

- Fly Fishing (1899)

See also

- Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology

- Timeline of British diplomatic history#1897-1919

- Temple Grove School

- Winchester College

References

- ↑ Finn, Margot C. "The Reform League, Union, and International". After Chartism: Class and Nation in English Radical Politics 1848-1874. Cambridge University Press. p. 259.

- ↑ Viscount Grey of Fallodon: Twenty-Five Years 1892-1916 (New York, 1925) p. 20 books.google.

- ↑ http://www.law.fsu.edu/library/collection/LimitsinSeas/IBS094.pdf p. 8.

- 1 2 3 thepeerage.com Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon

- ↑ Leach, Arthur F. A History of Winchester College. London and New York, 1899. Page 510

- ↑ Grey of Fallodon, "Twenty-five Years", vol.1, p.xxiv

- ↑ D Owen, "Military Conversations", p.

- ↑ Viscount Grey, Twenty Five Years, 1892–1916 (London, 1925) p.1.

- ↑ Viscount Grey, Twenty Five Years, p.10.

- ↑ Viscount Grey, Twenty Five Years, p.33.

- ↑ Viscount Grey, Twenty Five Years, 1892–1916 (London, 1925), p. 18.

- ↑ Quoted in Viscount Grey, Twenty Five Years, 1892–1916 (London, 1925), p.20.

- ↑ Viscount Grey, Twenty Five Years, 1892–1916 (London, 1925), p. 20.

- ↑ Viscount Grey, Twenty Five Years, 1892–1916 (London, 1925), p. 21.

- ↑ E & D Grey, Cottage Book, Itchen Abbas, 1894–1905 (London, 1909) entry of 22/23 June 1985.

- ↑ Keith Robbins, Sir Edward Grey. A Biography of Lord Grey of Fallodon (London, 1971) p.56.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 27464. p. 5174. 12 August 1902.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 27305. p. 2625. 16 April 1901.

- ↑ http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1908/feb/28/women's-enfranchisement-bill-1

- ↑ Beryl Williams, Great Britain and Russia, 1905 to the 1907 Convention p.133, in F. H. Hinsley (ed.), British Foreign Policy Under Sir Edward Grey (Cambridge, 1977)

- ↑ Beryl Williams, Great Britain and Russia, 1905 to the 1907 Convention p.133, in F. H. Hinsley (ed.), British Foreign Policy Under Sir Edward Grey (Cambridge, 1977), p. 134.

- ↑ Grey claimed that to the best of his recollection he had never used the phrase "balance of power," never consciously pursued it as a policy and was doubtful as to its precise meaning. Viscount Grey, Twenty Five Years 1892–1916 (London, 1925) pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Quoted in M.L. Dockrill, "British Policy During the Agadir Crisis of 1911" p. 276. in F.H. Hinsley (ed.), British Foreign Policy Under Sir Edward Grey (Cambridge, 1977

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 28581. p. 1169. 16 February 1912.

- ↑ Harry F Young, "The Misunderstanding of August 1, 1914," Journal of modern history (Dec 1976), 644-665.

- ↑ Sir Edward Grey, 3rd Baronet Encyclopaedia Britannica Article. Other common versions of the quote are

- The lights are going out all over Europe and I doubt we will see them go on again in our lifetime, (Sources Malta in Europe—a new dawn Department of Information—Government of Malta, 2000–2006. Ambassador Guenter Burghardt The State of the Transatlantic Relationship 4 June 2003)

- The lights are going out all over Europe: we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime, The lights are going out all over Europe William Wright, Editor Financial News Online US 6 March 2006

- ↑ Woodward, 1998, pp35

- ↑ Guinn 1965 pp.126-7

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 29689. p. 7565. 1 August 1916.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 31581. p. 12139. 3 October 1919.

- ↑ Koss 1985, p249

- ↑ Koss 1985, p251

- ↑ Jenkins 1964, p490-1

- ↑ Jenkins 1964, p490-1

- ↑ Koss 1985, p251

- ↑ Jenkins 1964, p491-2

- ↑ Chancellors of the University of Oxford University of Oxford

- ↑ Hastings, Max (2013). Catastrophe 1914. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-307-59705-2.

- ↑ Keith Robbins, Sir Edward Grey. A Biography of Lord Grey of Fallodon, (London, 1971) pp. 15, 55.

- ↑ Viscount Grey, Fly Fishing, (London, 1899)

- ↑ The Complete Peerage, Volume XIII—Peerage Creations 1901–1938. St Catherine's Press. 1949. p. 230.

Bibliography

Books

Sir Edward Grey ; Flyfishing 1899, 1929 two new chapters were added.

Sir Edward Grey: On Sea trout 1913,

Sir Edward Grey : The Flyfisherman 1926

- Viscount Grey of Fallodon [E. Grey] (1925). Twenty-Five Years 1892-1916. 2 vols. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Gordon, H.S. (1937). Edward Grey of Fallodon and His Birds. London.

- Guinn, Paul (1965). British Strategy and Politics 1914-18. Clarendon. ASIN B0000CML3C.

- Hinsley, F.H., ed. (1977). British Foreign Policy Under Sir Edward Grey. Cambridge.

- Jenkins, Roy (1964). Asquith (first ed.). London: Collins. OCLC 243906913.

- Koss, Stephen (1985). Asquith. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-231-06155-1.

- Lowe, C.J.; Dockrill, M. L. Mirage of Power: British Foreign Policy 1902-1914. 3 vols.

- Lowe, C.J.; Dockrill, M. L. (1972). Mirage of Power: The Documents. 3: British Foreign Policy 1902-1922.

- Lutz, Hermann; Dickes, E. W. (1928). Lord Grey and the World War.

- Murray, Gilbert (1915). The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906-1915.

- Robbins, Keith (1971). Sir Edward Grey. A Biography of Lord Grey of Fallodon.

- Robbins, Keith (January 2011). "Grey, Edward, Viscount Grey of Fallodon (1862–1933)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33570. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Steiner, Zara (1969). The Foreign Office and Foreign Policy 1898–1914. London.

- Steiner, Zara (1977). Britain and the Origins of the First World War. London.

- Trevelyan, G.M. (1937). Grey of Fallodon; the Life of Sir Edward Grey.

- Waterhouse, Michael (2013). "Edwardian Requiem: A Life of Sir Edward Grey".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon. |

- Works by Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon at Internet Archive

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Sir Edward Grey

Buckle, George Earle (1922). "Grey of Fallodon, Edward Grey, 1st Viscount". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.).

Buckle, George Earle (1922). "Grey of Fallodon, Edward Grey, 1st Viscount". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.).- Grey's Speech of 3 August 1914 before the House of Commons ("We are going to suffer, I am afraid, terribly in this war, whether we are in it or whether we stand aside.")

- The Genesis of the "A.B.C." Memorandum of 1901.

.svg.png)