Malagasy cuisine

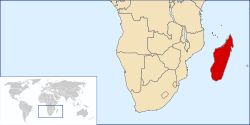

Malagasy cuisine encompasses the many diverse culinary traditions of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. Foods eaten in Madagascar reflect the influence of Southeast Asian, African, Indian, Chinese and European migrants that have settled on the island since it was first populated by seafarers from Borneo between 100 CE and 500 CE. Rice, the cornerstone of the Malagasy diet, was cultivated alongside tubers and other Southeast Asian staples by these earliest settlers. Their diet was supplemented by foraging and hunting wild game, which contributed to the extinction of the island's bird and mammal megafauna. These food sources were later complemented by beef in the form of zebu introduced into Madagascar by East African migrants arriving around 1,000 CE. Trade with Arab and Indian merchants and European transatlantic traders further enriched the island's culinary traditions by introducing a wealth of new fruits, vegetables, and seasonings.

Throughout almost the entire island, the contemporary cuisine of Madagascar typically consists of a base of rice served with an accompaniment; in the official dialect of the Malagasy language, the rice is termed vary ([ˈvarʲ]), and the accompaniment, laoka ([ˈlokə̥]). The many varieties of laoka may be vegetarian or include animal proteins, and typically feature a sauce flavored with such ingredients as ginger, onion, garlic, tomato, vanilla, salt, curry powder, or, less commonly, other spices or herbs. In parts of the arid south and west, pastoral families may replace rice with maize, cassava, or curds made from fermented zebu milk. A wide variety of sweet and savory fritters as well as other street foods are available across the island, as are diverse tropical and temperate-climate fruits. Locally produced beverages include fruit juices, coffee, herbal teas and teas, and alcoholic drinks such as rum, wine, and beer.

The range of dishes eaten in Madagascar in the 21st century offers insight into the island's unique history and the diversity of the peoples who inhabit it today. The complexity of Malagasy meals can range from the simple, traditional preparations introduced by the earliest settlers, to the refined festival dishes prepared for the island's 19th-century monarchs. Although the classic Malagasy meal of rice and its accompaniment remains predominant, over the past 100 years other food types and combinations have been popularized by French colonists and immigrants from China and India. Consequently, Malagasy cuisine is traditional while also assimilating newly emergent cultural influences.

History

Prior to 1650

Austronesian seafarers are believed to have been the first humans to settle on the island, arriving between 100 and 500 CE.[2] In their outrigger canoes they carried food staples from home including rice, plantains, taro, and water yam.[3] Sugarcane, ginger, sweet potatoes, pigs and chickens were also probably brought to Madagascar by these first settlers, along with coconut and banana.[3] The first concentrated population of human settlers emerged along the southeastern coast of the island, although the first landfall may have been made on the northern coast.[4] Upon arrival, early settlers practiced tavy (swidden, "slash-and-burn" agriculture) to clear the virgin coastal rainforests for the cultivation of crops. They also gathered honey, fruits, bird and crocodile eggs, mushrooms, edible seeds and roots, and brewed alcoholic beverages from honey and sugar cane juice.[5]

Game was regularly hunted and trapped in the forests, including frogs, snakes, lizards, hedgehogs and tenrecs, tortoises, wild boars, insects, larvae, birds and lemurs.[6] The first settlers encountered Madagascar's wealth of megafauna, including giant lemurs, elephant birds, giant fossa and the Malagasy hippopotamus. Early Malagasy communities may have eaten the eggs and—less commonly—the meat of Aepyornis maximus, the world's largest bird, which remained widespread throughout Madagascar as recently as the 17th century.[7] While several theories have been proposed to explain the decline and eventual extinction of Malagasy megafauna, clear evidence suggests that hunting by humans and destruction of habitats through slash-and-burn agricultural practices were key factors.[8][9] Although it has been illegal to hunt or trade any of the remaining species of lemur since 1964, these endangered animals continue to be hunted for immediate local consumption in rural areas or to supply the demand for exotic bush meat at some urban restaurants.[10]

As more virgin forest was lost to tavy, communities increasingly planted and cultivated permanent plots of land.[12] By 600 CE, groups of these early settlers had moved inland and begun clearing the forests of the central highlands. Rice was originally dry planted or cultivated in marshy lowland areas, which produced low yields. Irrigated rice paddies were adopted in the highlands around 1600, first in Betsileo country in the southern highlands, then later in the northern highlands of Imerina.[11] By the time terraced paddies emerged in central Madagascar over the next century,[11] the area's original forest cover had largely vanished. In its place were scattered villages ringed with nearby rice paddies and crop fields a day's walk away, surrounded by vast plains of sterile grasses.[2]

Zebu, a form of humped cattle, were introduced to the island around 1000 CE by settlers from east Africa, who also brought sorghum, goats, possibly Bambara groundnut, and other food sources. Because these cattle represented a form of wealth in east African and consequently Malagasy culture, they were eaten only rarely, typically after their ritual sacrifice at events of spiritual import such as funerals.[2] Fresh zebu milk and curds instead constituted a major part of the pastoralists' diet.[13] Zebu were kept in large herds in the south and west, but as individual herd members escaped and reproduced, a sizable population of wild zebu established itself in the highlands. Merina oral history tells that highland people were unaware that zebu were edible prior to the reign of King Ralambo (ruled 1575–1612), who is credited with the discovery, although archaeological evidence suggests that zebu were occasionally hunted and consumed in the highlands prior to Ralambo's time. It is more likely that these wild herds were first domesticated and kept in pens during this period, which corresponds with the emergence of complex, structured polities in the highlands.[2]

Foods were commonly prepared by boiling in water (at first using green bamboo as a vessel, and later clay or iron pots),[14] roasting over a fire or grilling over hot stones or coals.[6] Fermentation was also used to create curds from milk, develop the flavor of certain dried or fresh tubers or produce alcoholic beverages from honey, sugar cane juice or other local plants.[5] The techniques of sun curing (drying), smoking and salting were used to preserve various foods for transport, trade or future consumption. Many foods prepared in these ways, such as a smoked dried beef called kitoza ([kiˈtuzə̥]) and salted dried fish, are still eaten in a similar form in modern-day Madagascar.[15]

By the 16th century, centralized kingdoms had emerged on the west coast among the Sakalava and in the Central highlands among the Merina. The Merina sovereigns celebrated the new year with an ancient Merina ceremony called the Royal Bath (fandroana). For this ceremony, a beef confit called jaka ([ˈdzakə̥]) was prepared by placing beef in a decorative clay jar and sealing it with suet, then conserving it in an underground pit for a year. The jaka would be shared with friends at the following year's festival. As a dessert, revelers would eat rice boiled in milk and drizzled with honey, a preparation known as tatao ([taˈtau̯]). According to oral history, King Ralambo was the originator of these culinary traditions in Imerina.[16] Ralambo's father, King Andriamanelo, is credited with introducing the marriage tradition of the vodiondry ([vudiˈuɳɖʳʲ]) or "rump of the sheep," wherein the most favored cut of meat—the hindquarters—was offered by the groom to the parents of the bride-to-be at an engagement ceremony.[17] In contemporary Malagasy society the terminology persists but families are more likely to offer symbolic coins in place of an offering of food.[18]

1650–1800

The advent of the trans-Atlantic slave trade increased maritime trade at Malagasy ports, including food products. In 1696, a trading vessel en route to the American colonies reportedly took a stock of local Malagasy rice to Charleston, South Carolina, where the grain formed the basis of the plantation industry.[19] Trading ships brought crops from the Americas—such as sweet potato, tomato, maize, peanuts, tobacco and lima beans—to Madagascar in the 16th and 17th centuries;[2] cassava arrived after 1735 from a French colony at nearby Réunion Island.[20] These products were first cultivated in coastal areas nearest to their ports of arrival, but soon spread throughout the island; within 100 years of their introduction they were widespread throughout the central highlands.[21] Similarly, pineapple and citrus fruits such as lemons, limes, oranges, consumed by sailors to ward off scurvy on long cross-Atlantic trips, were introduced at coastal Malagasy ports. Local cultivation began soon afterward.[22]

The prickly pear cactus or raketa ([raˈketə̥]), also known in southern Madagascar as sakafon-drano ([saˈkafuˈɳɖʳanʷ]) or "water food", was brought from the New World to the French settlement at Fort Dauphin in 1769 by Frenchman Count Dolisie de Maudave. The plant spread throughout the southern part of the island, where it became a fundamental food crop for Mahafaly and Bara pastoralists. Consuming six or so of the fruits of this plant preempted the need to drink water, and once the spines had been removed, the cladodes of the plant would nourish and hydrate the zebu cattle they tended. The introduction of this plant enabled the southern pastoralists to become more sedentary and efficient herders, thus boosting population density and cattle count in the region.[23]

1800–1896

The 18th century in the central highlands was characterized by increasing population density and consequent famines, aggravated by warring among the principalities of Imerina. At the turn of the 19th century, King Andrianampoinimerina (1787–1810) successfully united these fractious Merina groups under his rule, then used slaves and forced labor—exacted in lieu of taxes for those without means to offer material payment—to systematically work the irrigated rice fields around Antananarivo. In this way, he ensured regular grain surpluses that were sufficient to consistently feed the entire population and export products for trade with other regions of the island. Marketplaces were established across the island to serve as central trading points for designated commodities such as smoked and dried seafood and meats, dried maize, salt, dried cassava and various fruits.[24] Rice cakes, including mofo gasy ([ˈmufʷˈɡasʲ]) and menakely ([menə̥ˈkelʲ]), were also sold by market vendors.[25] By this period, coastal cuisine had likewise evolved: early 19th century voyagers reported eating dishes on Île Sainte-Marie prepared with curry powder (including a spiced rice resembling biryani) and drinking coffee and tea.[26] Andrianampoinimerina's son, Radama I, succeeded in uniting nearly the entire island under his rule, and established the Kingdom of Madagascar. A line of Merina monarchs would continue to govern the island until its colonization by the French in 1896.[27]

Under the Kingdom of Madagascar, plantations were established for the production of crops exported to foreign markets such as England and France. Cloves were imported and planted in 1803, and coconuts—which had been relatively sparse on the island—were cultivated on plantations for the production of oil. Similarly, coffee had been grown on family plots of four to five trees until the early 19th century, when more intensive cultivation for export began.[28] Vanilla, later to become one of Madagascar's premiere export crops, was introduced by French entrepreneurs in 1840 and planted in eastern coastal rainforests. The technique of hand pollination, critical to higher vanilla yields, was introduced 30 years later.[29] Nonetheless, vanilla remained a marginal crop until the end of the monarchy.[30]

During Merina royal festivals, the hanim-pito loha ([amˈpitʷˈlu]) were eaten.[31] These were seven dishes said to be the most desirable in the realm. Among these dishes were voanjobory ([vwandzˈburʲ], Bambara groundnut), amalona ([aˈmalnə̥], eel), vorivorinkena ([vurvurˈkenə̥], beef tripe), ravitoto ([ravˈtutʷ], grated cassava leaves) and vorontsiloza ([vurntsʲˈluzə̥], turkey), each cooked with pork and usually ginger, garlic, onion and tomato; romazava ([rumaˈzavə̥], a stew of beef and greens) and varanga ([vaˈraŋɡə̥], shredded roast beef) completed the list.[32] Colonization of Madagascar by the French meant the end of the Malagasy monarchy and its elaborate feasts, but the traditions of this elegant cuisine were preserved in the home, where these dishes are eaten regularly. They are also served in many restaurants throughout the island.[31]

1896–1960

French colonial rule began in 1896 and introduced a number of innovations to local cuisines. Certain new food names derived from the French language—then the dominant language of the state[33]—became widespread. Baguettes were popularized among cosmopolitan urbanites, as were a variety of French pastries and desserts such as cream horns, mille-feuille, croissants and chocolat chaud (hot chocolate). The French also introduced foie gras, now produced locally,[34] and popularized a dish known in the highlands as composé: a cold macaroni salad mixed with blanched vegetables based on the French macédoine de légumes.[35] The French established plantations for the cultivation of a variety of cash crops, including not only those already exploited in the 19th century, but new foreign fruits, vegetables and livestock, with varying degrees of success. Tea, coffee, vanilla, coconut oil and spices became successful exports.[36] Coconut became a regular ingredient in coastal cuisine, and vanilla began to be used in sauces for poultry and seafood dishes.[37]

Although a handful of Chinese settlers had arrived in Madagascar towards the end of the reign of Queen Ranavalona III, the first major influx of Chinese migrants followed an announcement by General Joseph Gallieni, first governor general of the colony of Madagascar, requesting 3,000 Chinese laborers to construct a northern rail line between Antananarivo and Toamasina.[38] Chinese migrants introduced a number of dishes that have become part of urban popular cuisine in regions with large Chinese communities, including riz cantonais (Chinese fried rice), soupe chinoise (Chinese-style noodle soup), misao (fried noodles), pao (hum bao)[39] and nems (fried egg rolls).[40]

By the 1880s, a community of roughly 200 Indian traders had been established at Mahajanga, a port on the north-west coast of Madagascar, near Bembatoka Bay at the mouth of the Betsiboka River.[41] Thirty years later the population of Indians in Madagascar had increased to over 4,000, concentrated along the trading ports of the northwestern coast.[42] These early Indian communities popularized curries and biryanis throughout the region. Khimo in particular, a dish based on the Indian keema, became a specialty of Mahajanga.[43] Indian samosas (sambos) soon became a popular street food in most parts of Madagascar, where they may also be known by the name tsaky telozoro ([ˈtsakʲteluˈzurʷ], "three-cornered snack").[44]

While French innovations enriched the cuisine in many ways, not every innovation was favorable. Since the French introduction of the prickly pear cactus in the 18th century, the lifestyle of southern pastoralists became increasingly reliant on the plant to ensure food and water for their zebu as well as fruit and water for themselves during the dry season between July and December. However, in 1925, a French colonist wishing to eradicate the cactus on his property in the southwestern town of Toliara introduced the cochineal, an insect known to be a parasite of the plant. Within five years, nearly all the prickly pear cactus of southern Madagascar had been completely wiped out, sparking a massive famine from 1930–1931.[45] Although these ethnic groups have since adapted in various ways, the famine period is commonly remembered as the time when their traditional lifestyle was ended by the arrival of foreigners on their land.[45]

Contemporary cuisine

Since Madagascar gained independence from French colonial rule in 1960, Malagasy cuisine has reflected the island's diverse cultures and historic influences. Throughout the country, rice is considered the preeminent food and constitutes the main staple of the diet in all but the most arid regions of the south and west.[46] Accompanying dishes served with rice vary regionally according to availability of ingredients and local cultural norms. Outside the home, Malagasy cuisine is served at simple roadside stalls (gargottes) or sit-down eateries (hotely). Snacks and rice-based meals may also be purchased from ambulatory street vendors. Upscale restaurants offer a wider variety of foreign cuisine and Malagasy dishes bearing French and other outside influences in preparation technique, ingredients and presentation alike.[32]

Rice (vary)

Rice (vary) is the cornerstone of the Malagasy diet and is typically consumed at every meal.[47] The verb "to eat a meal" in the Malagasy language is commonly mihinam-bary – literally, to eat rice.[47] Rice may be prepared with varying amounts of water to produce a fluffy dry rice (vary maina, [ˌvarʲ ˈmajnə̥]) eaten with some kind of accompaniment (laoka) in sauce. It may also be prepared with extra water to produce a soupy rice porridge called vary sosoa ([ˌvarʲ suˈsu]) which is typically eaten for breakfast or prepared for the sick.[48] Vary sosoa may be accompanied with a dry laoka such as kitoza, smoked strips of zebu meat.[49] A popular variation, vary amin'anana ([ˈvarʲ ˌjamʲˈnananə̥]), is a traditional porridge made with rice, meat and chopped greens.[50] During a highland famadihana (reburial ceremony), a special kind of rice called vary be menaka ([ˈvarʲ beˈmenakə̥], "rice with much fat") is rice served with fatty chunks of beef or preferably, highly fatty chunks of pork.[32]

Accompaniment (laoka)

The accompaniment served with rice is called laoka in the highlands dialect,[47] the official version of the Malagasy language. Laoka are most often served in some kind of sauce: in the highlands, this sauce is generally tomato-based, while in coastal areas coconut milk is often added during cooking.[32] In the arid southern and western interior where herding zebu is traditional, fresh or curdled zebu milk is often incorporated into vegetable dishes.[53] Laoka are diverse and may include such ingredients as Bambara groundnuts with pork, beef or fish; trondro gasy, ([ˌtʂundʐʷ ˈɡasʲ], various freshwater fish); shredded cassava leaves with peanuts, beef or pork; henan'omby ([henˈnumbʲ], beef) or akoho ([aˈkuː], chicken) sauteed with ginger and garlic or simmered in its own juices (a preparation called ritra [ˈritʂə̥]); various types of seafood, which are more readily available along the coasts or in large urban centers; and many more.[54][55] A variety of local greens such as anamamy ([anaˈmamʲ], Morelle greens), anamafaitra (Malagasy pronunciation: [anaˈmafai̯ʈʳ], Martin greens) and particularly anamalao (Malagasy pronunciation: [anamaˈlau̯], paracress)—distinguished by the mildly analgesic effect the boiled leaves and flowers produce—are commonly sold alongside anandrano (Malagasy pronunciation: [ananˈɖʳanʷ], watercress) and anatsonga (Malagasy pronunciation: [anaˈtsuŋɡə̥], bok choy).[56] In the arid south and west, such as among the Bara or Tandroy peoples, staples include sweet potato, yams, taro root and especially cassava, millet and maize, generally boiled in water and occasionally served in whole milk or flavored with crushed peanuts.[57]

Garlic, onions, ginger, tomatoes, mild curry, and salt are the most common ingredients used to flavor dishes, and in coastal areas other ingredients such as coconut milk, vanilla, cloves or turmeric may also be used.[58] A variety of condiments are served on the side and mixed into the rice or laoka according to each individual's taste rather than mixing them in as the food is being cooked.[59] The most common and basic condiment, sakay ([saˈkai̯]), is a spicy condiment made from red or green chili pepper.[60] Indian-style condiments made of pickled mango, lemon, and other fruits (known as achards or lasary [laˈsarʲ]), are a coastal specialty;[1] in the highlands, lasary often refers to a salad of green beans, cabbage, carrots and onion in a vinaigrette sauce, popular as a side dish or as the filling of a baguette sandwich.[61]

Ro ([ru], a broth) may be served as the main laoka or in addition to it to flavor and moisten the rice. Ro-mangazafy ([rumaŋɡaˈzafʲ]) is a rich and flavorful broth made with beef, tomato and garlic that often accompanies a dry laoka.[62] By contrast, Romatsatso ([rumaˈtsatsʷ]) is a light and relatively flavorless broth made with onion, tomato and anamamy greens served with meat or fatty poultry.[63] Ron-akoho ([runaˈku]), a broth made with chicken and ginger, is a home remedy for the common cold,[63] while rompatsa ([rumˈpatsə̥])—a broth made with tiny dried shrimp and beef, to which sweet potato leaves and potato are often added—is traditionally eaten by new mothers to support lactation.[52] The national dish is the broth called romazava, which in its simplest form is made of beef with anamalao, anantsonga or anamamy, although ingredients such as tomato, onion and ginger are commonly added to create more complex and flavorful versions. Romazava is distinguished by its inclusion of anamalao flowers, which produce a mild analgesic effect when the broth is consumed.[64]

Street foods

A variety of cakes and fritters collectively known as mofo ([ˈmuf], meaning "bread") are available from kiosks in towns and cities across Madagascar.[65] The most common is mofo gasy, meaning "Malagasy bread", which is made from a batter of sweetened rice flour poured into greased circular molds and cooked over charcoal. Mofo gasy is a popular breakfast food and is often eaten with coffee, also sold at kiosks.[66] In coastal areas this mofo is made with coconut milk and is known as mokary ([muˈkarʲ]).[67] Other sweet mofo include a deep-fried doughnut called menakely[68] and a fried dough ball called mofo baolina ([ˌmuf ˈbolː]),[69] as well as a variety of fruit fritters, with pineapple and bananas among the most common fruits used.[70] Savory mofo include ramanonaka ([ˌramaˈnunakə̥]), a mofo gasy salted and fried in lard,[71] and a fritter flavored with chopped greens, onions, tomatoes and chilies called mofo sakay ([ˌmuf saˈkai̯], meaning "spicy bread").[72]

In marketplaces and gas stations one may find vendors selling koba akondro ([kubaˈkundʐʷ]), a sweet made by wrapping a batter of ground peanuts, mashed bananas, honey and corn flour in banana leaves and steaming or boiling the small cakes until the batter has set.[32][73] Peanut brittle, dried bananas, balls of tamarind paste rolled in colored sugar, deep-fried wonton-type dough strings called kaka pizon ([kaka pizõ], meaning "pigeon droppings") also eaten in neighboring Reunion Island, and home-made yogurts, are all commonly sold on the street.[74] In rural areas, steamed cassava or sweet potatoes are eaten, occasionally with fresh or sweetened condensed milk.[73]

Desserts

Traditionally, fresh fruit may be eaten after a meal as a dessert.[75] Fresh sugarcane may also be chewed as a treat.[76] A great variety of temperate and tropical fruits are grown locally and may be enjoyed fresh or sprinkled with sugar. Temperate fruits found in Madagascar include but are not limited to apples, lemons, pumpkins, watermelon, oranges, cherries and strawberries. Among the many tropical fruits commonly eaten in Madagascar are coconut, tamarind, mango, pineapple, avocado, passion fruit, and loquats, locally called pibasy ([piˈbasʲ]). Guava, longans, lychees, persimmon and "pok-pok" (also called voanantsindrana [vunˈtsinɖʳanə̥]), a fruit similar to a physalis, are common, while on the west coast the fruit of the baobab tree is eaten during the brief period when it becomes available near the end of the rainy season.[77]

Madagascar is known for its high-quality cocoa[78][79] and vanilla,[80] much of which are exported. In the coastal areas of Madagascar or in upscale inland restaurants, vanilla may be used to prepare savory sauces for poultry.[81]

Koban-dravina ([ˌkubanˈɖʳavʲnə̥]) or koba ([ˈkubə̥]) is a Malagasy specialty made by grinding together peanuts and brown sugar, then enveloping the mixture in a sweetened rice flour paste to produce a cylindrical bundle. The bundle is wrapped in banana leaves and boiled for 24 to 48 hours or longer until the sugar becomes caramelized and the peanuts have softened. The resulting cake is served in thin slices. Bonbon coco is a popular candy made from shredded coconut cooked with caramelized sugar and formed into chewy balls or patties. A firm, cake-like coconut milk pudding known as godro-godro ([ɡuɖʳˈɡuɖʳʷ]) is a popular dessert also found in Comoros.[82] French pastries and cakes are very popular across the island and may be purchased at the many pâtisseries found in towns and cities throughout Madagascar.[83]

Beverages

_in_Madagascar.jpg)

Ranon'ampango ([ˌranʷnamˈpaŋɡʷ])[84] and ranovola ([ranʷˈvulə̥]),[85] are the most common and traditional beverages in Madagascar. Both are names for a drink made by adding hot water to the toasted rice left sticking to the interior of its cooking pot. This drink is a sanitary and tasty alternative to fresh water.[75]

In addition, a variety of other drinks are produced locally.[86] Coffee is grown in the eastern part of the island and has become a standard breakfast drink, served black or with sweetened condensed milk at street-side kiosks. Black tea, occasionally flavored with vanilla, and herbal teas—particularly lemongrass and lemon bush (ravin'oliva [ˌravʲnoˈlivə̥])—are popular. Juices are made from guava, passion fruit, pineapple, tamarind, baobab, and other fruit. Fresh milk, however, is a luxury, and locally produced yogurts, ice creams or sweetened condensed milk mixed with hot water are the most common dairy sources of calcium. Cola and orange soft drinks are produced locally, as is Bonbon Anglais, a local sweet lemon soda. Coca-Cola products are popular and widely consumed throughout the island.[87]

Numerous alcoholic beverages are produced for local consumption and limited export.[66] The local pilsner, Three Horses Beer, is popular and ubiquitous. Wine is produced in the southern highlands around Fianarantsoa, and rum (toaka gasy [ˌtokə̥ ˈɡasʲ]) is widely produced and can be either drunk neat, flavored with exotic fruits and spices to produce rhum arrangé or blended with coconut milk to make a punch coco cocktail.[87] The most traditional form of rum, called betsabetsa [ˌbetsəˈbetsə̥], is made from fermented sugarcane juice. Rum serves a ritual purpose in many parts of Madagascar, where it is traditional to throw the first capful of a newly opened bottle of rum into the northeast corner of the room as an offering and gesture of respect to the ancestors.[88] At social gatherings it is common for alcoholic beverages to be accompanied with savory, fried snacks known collectively as tsakitsaky, commonly including pan-fried peanuts, potato chips, nems, sambos and kaka pizon.[89]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Espagne-Ravo (1997), pp. 79–83

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gade (1996), p. 105

- 1 2 Blench (1996), pp. 420–426

- ↑ Campbell (1993), pp. 113–114

- 1 2 Sibree (1896), p. 333

- 1 2 Stiles, D. (1991). "Tubers and Tenrecs: the Mikea of Southwestern Madagascar". Ethnology. 30 (3): 251–263. doi:10.2307/3773634.

- ↑ Presenter: David Attenborough; Director: Sally Thomson; Producer: Sally Thomson; Executive Producer: Michael Gunton (March 2, 2011). BBC-2 Presents: Attenborough and the Giant Egg. BBC.

- ↑ Virah-Sawmy, M.; Willis, K.J.; Gillson, L. (2010). "Evidence for drought and forest declines during the recent megafaunal extinctions in Madagascar". Journal of Biogeography. 37 (3): 506–519. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02203.x.

- ↑ Perez, V.R.; Godfrey, L.R.; Nowak-Kemp, M.; Burney, D.A.; Ratsimbazafy, J.; Vasey, N. (2005). "Evidence of early butchery of giant lemurs in Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution. 49 (6): 722–742. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.08.004. PMID 16225904.

- ↑ Butler, Rhett (July 17, 2005). "Lemur hunting persists in Madagascar: Rare primates fall victim to hunger". mongabay.org. Archived from the original on April 28, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Campbell (1993), p. 116

- ↑ Olson, S. (1984). "The robe of the ancestors: Forests in the history of Madagascar". Journal of Forest History. 28 (4): 174–186. doi:10.2307/4004807.

- ↑ Linton (1928), p. 386

- ↑ Linton (1928), p. 367

- 1 2 Grandidier (1899), p. 521

- ↑ Raison-Jourde, Françoise (1983). Les Souverains de Madagascar (in French). Antananarivo, Madagascar: Karthala Editions. p. 29. ISBN 2-86537-059-3.

- ↑ Kent, Raymond (1970). Early Kingdoms in Madagascar: 1500–1700. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 93. ISBN 0-03-084171-2.

- ↑ Bloch, Maurice (1997). Placing the dead: tombs, ancestral villages and kinship organization in Madagascar. London: Berkeley Square House. pp. 179–180. ISBN 0-12-809150-9.

- ↑ Campbell (1993), pp. 131

- ↑ Jones, William (1957). "Manioc: An example of innovation in African economies". Economic Development and Cultural Change. 5 (2): 97–117. doi:10.1086/449726.

- ↑ Campbell (1993), p. 117

- ↑ Campbell (1993), pp. 127, 142

- ↑ Kaufmann, J.C. (2000). "Forget the Numbers: The Case of a Madagascar Famine". History in Africa. 27: 143–157. doi:10.2307/3172111.

- ↑ Campbell (1993), p. 125

- ↑ Sibree, James (1885). The Antananarivo annual and Madagascar magazine. Volume 3. Antananarivo, Madagascar: London Missionary Society Press. p. 405.

- ↑ Robinson, Heaton (1831). Narrative of Voyages to Explore the Shores of Africa, Arabia, and Madagascar. Volume 1. New York: J & J Harper. p. 112.

- ↑ Mutibwa, P.M.; Esoavelomandroso, F.V. (1989). "Madagascar: 1800–80". In Ade Ajayi, Jacob Festus. General History of Africa VI: Africa in the Nineteenth Century until the 1880s. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 412–447. ISBN 0-520-06701-0.

- ↑ Campbell (2005), p. 107

- ↑ Karner, Julie (2006). The Biography of Vanilla. New York: Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 22. ISBN 0-7787-2490-5.

- ↑ Wildeman, Emile (1902). Les plantes tropicales de grande culture (in French). Paris: Maison d'édition A. Castaigne. pp. 147–148.

- 1 2 Auzias et al (2009), p. 150

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bradt (2011), p. 312

- ↑ Spolsky, Bernard (2004). Language Policy. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-521-01175-2.

- ↑ Auzias et al (2009), p. 92

- ↑ Chan Tat Chuen (2010), p. 51

- ↑ Campbell (2005), pp. 107–111

- ↑ Donenfeld (2007), p. xix

- ↑ McLean Thompson, Virginia; Adloff, Richard (1965). The Malagasy Republic: Madagascar today. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 271. ISBN 0-8047-0279-9.

- ↑ Andrew, David; Blond, Becca; Parkinson, Tom; Anderson, Aaron (2008). Madagascar & Comoros. Melbourne, Australia: Lonely Planet. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-74104-608-3.

- ↑ Savoir Cuisiner (2004), p. 5

- ↑ Oliver (1885), p. 115

- ↑ Martin, Frederick (1916). "Madagascar". The Statesman's Year-book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1916. London: St. Martin's Press. pp. 905–908.

- ↑ Espagne-Ravo (1997), p. 97

- ↑ Espagne-Ravo (1997), pp. 21–27

- 1 2 Middleton, Karen (1997). "Death and Strangers". Journal of Religion in Africa. 27 (4): 341–373. doi:10.1163/157006697x00199.

- ↑ Faublée (1942), p. 157

- 1 2 3 Sibree, James (1915). A Naturalist in Madagascar. London: J.B. Lippincott Company. p. 106.

- ↑ Boissard (1997), p. 30

- ↑ Savoir Cuisiner (2004), p. 26

- ↑ Savoir Cuisiner (2004), pp. 30–31

- ↑ Savoir Cuisiner (2004), p. 46

- 1 2 Ficarra, Vanessa; Thiam, Aminata; Vololonirina, Dominique (2006). Universalisme du lien mère-enfant et construction culturelle des pratiques de maternage. Cours OIP-505A Semiotique de la culture et communication interculturelle (in French). INALCO-CFI/OIPP. p. 51. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ↑ Faublée (1942), pp. 194–196

- ↑ Espagne-Ravo (1997)

- ↑ Savoir Cuisiner (2004)

- ↑ Savoir Cuisiner (2004), p. 7

- ↑ Faublée (1942), pp. 192, 194–196

- ↑ Jacob, Jeanne; Michael, Ashkenazi (2006). The World Cookbook for Students. Volume 3, Iraq to Myanmar. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 128–133. ISBN 0-313-33454-4.

- ↑ Chan Tat Chuen (2010), pp. 37–38

- ↑ Chan Tat Chuen (2010), p. 42

- ↑ Chan Tat Chuen (2010), p. 39

- ↑ Boissard (1997), p. 32

- 1 2 Boissard (1997), p. 34

- ↑ Boissard (1997), pp. 36–40

- ↑ Boissard (1997), p. 80

- 1 2 Bradt (2011), pp. 101–102

- ↑ Donenfeld (2007), p. 7

- ↑ Chan Tat Chuen (2010), pp. 97–98

- ↑ Savoir Cuisiner (2004), pp. 18–19

- ↑ Espagne-Ravo (1997), pp. 131–132

- ↑ Jeanguyot, Michelle; Ahmadi, Nour (2002). Grain de riz, grain de vie (in French). Paris: Editions Quae. p. 87. ISBN 2-914330-33-2.

- ↑ Ranaivoson, Dominique (2007). 100 mots pour comprendre Madagascar (in French). Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose. pp. 18–19. ISBN 2-7068-1944-8.

- 1 2 Weber, Katharine (2010). True Confections. New York: Random House. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-307-39586-3.

- ↑ Pitcher, Gemma; Wright, Patricia (2004). Madagascar & Comoros. Melbourne, Australia: Lonely Planet. p. 37. ISBN 1-74104-100-7.

- 1 2 Sandler, Bea (2001). The African Cookbook. New York: Citadel Press. pp. 85–94. ISBN 0-8065-1398-5. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- ↑ Faublée (1942), p. 174

- ↑ Janick, Jules; Paull, Robert E., eds. (2008). "Bombacaceae: Adansonia Digitata Baobab". The Encyclopedia of Fruit & Nuts. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cabi Publishing. pp. 174–176. ISBN 978-0-85199-638-7.

- ↑ Hubert, Diana (August 3, 2010). "Chocolate made in Madagascar: A Labor of Love (Photo Gallery)". The Epoch Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ↑ Motavalli, Jim (November–December 2007). "Sweet Dreams: Fair trade cocoa company Theo Chocolate". E: The Environmental Magazine. pp. 42–43. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ↑ Ecott, Tim (2004). Vanilla: Travels in search of the Luscious Substance. London: Penguin Books. p. 222. ISBN 0-7181-4589-5.

- ↑ Chan Tat Chuen (2010), p. 62

- ↑ Nativel & Rajaonah (2009), p. 152

- ↑ Bradt & Austin (2007), pp. 165–166

- ↑ Espagne-Ravo (1997), p. 39

- ↑ Savoir Cuisiner (2004), p. 27

- ↑ Bradt & Austin (2007), p. 115

- 1 2 Bradt & Austin (2007), p. 114

- ↑ Nativel & Rajaonah (2009), p. 165

- ↑ Chan Tat Chuen (2010), pp. 49–57

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuisine of Madagascar. |

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul; Mauro, Didier; Raholiarisoa, Emeline (2009). Le Petit Futé Madagascar (in French). Paris: Petit Futé. ISBN 2-7469-2684-9.

- Blench, Roger (1996). "The Ethnographic Evidence for Long-Distance Contacts Between Oceania and East Africa". In Reade, Julian. The Indian Ocean in Antiquity. London: British Museum. pp. 417–438. ISBN 0-7103-0435-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2010.

- Boissard, Pierre (1997). Cuisine Malgache, Cuisine Creole (in French). Antananarivo, Madagascar: Librairie de Tananarive.

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2007). Madagascar (9th ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. ISBN 978-1-84162-197-5.

- Bradt, Hilary (2011). Madagascar (10th ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. ISBN 978-1-84162-341-2.

- Campbell, Gwyn (1993). "The Structure of Trade in Madagascar, 1750–1810". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 26 (1): 111–148. doi:10.2307/219188.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2005). An economic history of Imperial Madagascar, 1750–1895: the rise and fall of an island empire. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83935-1.

- Chan Tat Chuen, William (2010). Ma Cuisine de Madagascar (in French). Paris: Jean-Paul Rocher Editeur. ISBN 978-2-917411-32-2.

- Donenfeld, Jill (2007). Mankafy Sakafo:Delicious meals from Madagascar. New York: iUniverse. pp. xix. ISBN 978-0-595-42591-4.

- Espagne-Ravo, Angéline (1997). Ma Cuisine Malgache: Karibo Sakafo (in French). Paris: Edisud. ISBN 2-85744-946-1.

- Faublée, Jacques (1942). "L'alimentation des Bara (Sud de Madagascar)". Journal de la Société des Africanistes (in French). 12 (12): 157–202. doi:10.3406/jafr.1942.2534. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- Gade, Daniel W. (1996). "Deforestation and its effects in Highland Madagascar". Mountain Research and Development. 16 (2): 101–116. doi:10.2307/3674005.

- Grandidier, A. (1899). Guide de l’immigrant à Madagascar (in French). Paris: A Colin et cie.

- Linton, R. (1928). "Culture Areas in Madagascar". American Anthropologist. 30 (3): 363–390. doi:10.1525/aa.1928.30.3.02a00010.

- Nativel, Didier; Rajaonah, Faranirina (2009). Madagascar revisitée: en voyage avec Françoise Raison-Jourde (in French). Paris: Editions Karthala. ISBN 978-2-8111-0174-9.

- Oliver, Samuel Pasfield (1885). The True Story of the French Dispute in Madagascar. London: T.F. Unwin.

- Savoir Cuisiner: La Cuisine de Madagascar (in French). Saint-Denis, Reunion: Editions Orphie. 2004. ISBN 2-87763-020-X.

- Sibree, James (1896). Madagascar before the conquest. London: T.F. Unwin.