Chronology of Jesus

A chronology of Jesus aims to establish a timeline for the historical events of the life of Jesus. The Christian gospels were not intended to be read like a modern news report or historical document. However, it is possible to correlate Jewish and Greco-Roman documents and astronomical calendars with the New Testament accounts to estimate date ranges for the major events in Jesus' life.

Two methods have been used to estimate the year of the birth of Jesus: one based on the accounts of his birth in the gospels with reference to King Herod's reign, and the other by working backwards from his stated age of "about 30 years" when he began preaching (most scholars, on this basis, assume a date of birth between 6 and 4 BC).[1]

Three details have been used to estimate the year when Jesus began preaching: a mention of his age of "about 30 years" during "the fifteenth year" in the reign of Tiberius Caesar, another relating to the date of the building of the Temple in Jerusalem, and the death of John the Baptist.[2][3][4][5][6][7] Hence, scholars estimate that Jesus began preaching, and gathering followers, around AD 28-29. According to the three synoptic gospels Jesus continued preaching for at least one year, and according to John for three years.[2][4][8][9][10]

Four main approaches have been used to estimate the date of the crucifixion of Jesus. One uses non-Christian sources such as Josephus and Tacitus.[11][12] Another works backwards from the historically well established trial of Apostle Paul in Achaea to estimate the date of Paul's conversion. Both approaches result in AD 36 as an upper bound to the crucifixion.[13][14][15] Thus, scholars generally agree that Jesus was crucified between 30AD and 36AD. [4][13][16][17] Astronomical point estimates developed by Newton focus on Friday 3 April AD 33 and, less frequently, Friday 7 April AD 30.[18] Recent astronomical research uses the contrast between the synoptic date of Jesus' last Passover on the one hand with John's date of the subsequent "Jewish Passover" on the other hand, to calculate Jesus' Last Supper to have been on Wednesday, 1 April AD 33 and the crucifixion on Friday 3 April AD 33.

| Part of a series on |

|

Context and overview

The Christian gospels do not claim to provide an exhaustive list of the events in the life of Jesus.[20][21][22] They were written as theological documents in the context of early Christianity rather than historical chronicles and their authors showed little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life with the secular history of the age.[23][24][25] One manifestation of the gospels being theological documents rather than historical chronicles is that they devote about one third of their text to just seven days, namely the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem, also known as the Passion of Christ.[26]

Although they provide few details regarding events which can be clearly dated, it is possible to establish some date ranges regarding the major events in his life via correlations with other sources.[23][24][27] A number of historical non-Christian documents, such as Jewish and Greco-Roman sources, have been used in historical analyses of the chronology of Jesus.[28] Virtually all modern historians agree that Jesus existed, and regard his baptism and his crucifixion as historical events, and assume that approximate ranges for these events can be estimated.[29][30][31]

Using these methods, most scholars assume a date of birth between 6 and 4 BC,[1] that Jesus' preaching began around AD 27-29 and lasted one to three years.[2][4][8][9] They calculate the death of Jesus as having taken place between AD 30 and 36.[4][13][16][17]

Historical birth date of Jesus

The date of birth of Jesus of Nazareth is not stated in the gospels or in any secular text, but most scholars assume a date of birth between 6 BC and 4 BC.[1] Two methods have been used to estimate the year of the birth of Jesus: one based on the accounts of his birth in the gospels with reference to King Herod's reign, and the other by working backwards from his stated age of "about 30 years" when he began preaching (Luke 3:23) in "the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar" (Luke 3:1-2): the two methods indicate a date of birth before Herod's death in 4 BC, and a date of birth around 2 BC, respectively.[1] [32]

Years of preaching

Reign of Tiberius and the Gospel of Luke

One method for the estimation of the date of the beginning of the ministry of Jesus is based on the Gospel of Luke's specific statement in Luke 3:1-2 about the ministry of John the Baptist which preceded that of Jesus:[2][3]

Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judaea, and Herod being tetrarch of Galilee, and his brother Philip tetrarch of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias tetrarch of Abilene, in the highpriesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of God came unto John the son of Zacharias in the wilderness.

The reign of Tiberius Caesar began on the death of his predecessor Augustus Caesar in September AD 14, implying that the ministry of John the Baptist began in late AD 28 or early AD 29.[33][34] Riesner's alternative suggestion is that John the Baptist began his ministry in AD 26 or 27, because Tiberius ruled together with Augustus for two years before becoming the sole ruler. If so, the fifteenth year of Tiberius' reign would be counted from AD 12.[15] Riesner's suggestion is however considered less likely, as all the major Roman historians who calculate the years of Tiberius' rule - namely Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio - count from AD 14 - the year of Augustus' death. In addition, coin evidence shows that Tiberius started to reign in AD 14.[35]

The New Testament presents John the Baptist as the precursor to Jesus and the Baptism of Jesus as marking the beginning of Jesus' ministry.[36][37][38] In his sermon in Acts 10:37-38, delivered in the house of Cornelius the centurion, Apostle Peter refers to what had happened "throughout all Judaea, beginning from Galilee, after the baptism which John preached" and that Jesus had then gone about "doing good".[39]

The Temple in Jerusalem and the Gospel of John

Another method for estimating the start of the ministry of Jesus without reliance on the Synoptic gospels is to relate the account in the Gospel of John about the visit of Jesus to Herod's Temple in Jerusalem with historical data about the construction of the Temple.[2][4][9]

John 2:13 says that Jesus went to the Temple in Jerusalem around the start of his ministry and in John 2:20 Jesus is told: "This temple has been under construction for forty-six years, and will you raise it up in three days?".[2][4]

Herod's Temple in Jerusalem was an extensive and long term construction on the Temple Mount, which was never fully completed even by the time it was destroyed by the Romans in 70AD.[40][41][42] Having built entire cities such as Caesarea Maritima, Herod saw the construction of the Temple as a key, colossal monument.[41] The dedication of the initial temple (sometimes called the inner Temple) followed a 17 or 18 month construction period, just after the visit of Augustus to Syria.[36][40]

Josephus (Ant 15.11.1) states that the temple's reconstruction was started by Herod in the 18th year of his reign.[2][16][43] But there is some uncertainty about how Josephus referred to and computed dates, which event marked the start of Herod's reign, and whether the initial date should refer to the inner Temple, or the subsequent construction.[4][9][36] Hence various scholars arrive at slightly different dates for the exact date of the start of the Temple construction, varying by a few years in their final estimation of the date of the Temple visit.[9][36] Given that it took 46 years of construction, the best scholarly estimate for when Jesus preached is around the year AD 29.[2][4][8][9][10][44][45]

Josephus' reference to John the Baptist

Both the gospels and first century historian Flavius Josephus, in his work Antiquities of the Jews,[46] refer to Herod Antipas killing John the Baptist, and to the marriage of Herod and Herodias, establishing two key connections between Josephus and the biblical episodes.[5] Josephus refers to the imprisonment and execution of John the Baptist by Herod Antipas and that Herodias left her husband to marry Herod Antipas, in defiance of Jewish law.[5][6][7][47]

Josephus and the gospels differ however on the details and motives, e.g. whether the execution was a consequence of the marriage of Herod Antipas and Herodias (as indicated in Matthew 14:4, Mark 6:18), or a pre-emptive measure by Herod which possibly took place before the marriage to quell a possible uprising based on the remarks of John, as Josephus suggests in Ant 18.5.2.[19][48][49][50]

_003.jpg)

The exact year of the marriage of Herod Antipas and Herodias is subject to debate among scholars.[6] While some scholars place the year of the marriage in the range AD 27-31, others have approximated a date as late as AD 35, although such a late date has much less support.[6] In his analysis of Herod's life, Harold Hoehner estimates that John the Baptist's imprisonment probably occurred around AD 30-31.[51] The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia estimates the death of the Baptist to have occurred about AD 31-32.[7]

Josephus stated (Ant 18.5.2) that the AD 36 defeat of Herod Antipas in the conflicts with Aretas IV of Nabatea was widely considered by the Jews of the time as misfortune brought about by Herod's unjust execution of John the Baptist.[50][52][53] Given that John the Baptist was executed before the defeat of Herod by Aretas, and based on the scholarly estimates for the approximate date of the marriage of Herod Antipas and Herodias, the last part of the ministry of John the Baptist and hence parts of the ministry of Jesus fall within the historical time span of AD 28-35, with the later year 35 having the least support among scholars.[6][53][54]

Date of death

Prefecture of Pontius Pilate

All four Canonical gospels state that Jesus was crucified during the prefecture of Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea.[55][56]

In the Antiquities of the Jews (written about AD 93), Josephus states (Ant 18.3) that Jesus was crucified on the orders of Pilate.[57] Most scholars agree that while this reference includes some later Christian interpolations, it originally included a reference to the execution of Jesus under Pilate.[58][59][60][61][62]

In the second century the Roman historian Tacitus[63][64] in The Annals (c. AD 116), described the persecution of Christians by Nero and stated (Annals 15.44) that Jesus had been executed on the orders of Pilate[57][65][65] during the reign of Tiberius (Emperor from 18 September AD 14 - 16 March AD 37).

According to Flavius Josephus,[66] Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea from AD 26 until he was replaced by Marcellus, either in AD 36 or AD 37, establishing the date of the death of Jesus between AD 26 and AD 37.[67][68][69]

Reign of Herod Antipas

In the Gospel of Luke, while Jesus is in Pilate's court, Pilate realizes that Jesus is a Galilean and thus is under the jurisdiction of Herod Antipas.[70][71] Given that Herod was in Jerusalem at that time, Pilate decided to send Jesus to Herod to be tried.[70][71]

This episode is described only in the Gospel of Luke (23:7-15).[72][73][74][75] While some scholars have questioned the authenticity of this episode, given that it is unique to the Gospel of Luke, the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia states that it fits well with the theme of the gospel.[7]

Herod Antipas, a son of Herod the Great, was born before 20 BC and was exiled in the summer of AD 39 following a lengthy intrigue involving Caligula and Agrippa I, the grandson of his father.[76][77] This episode indicates that Jesus' death took place before AD 39.[78][79]

Conversion of Paul

Another approach to estimating an upper bound for the year of death of Jesus is the estimation of the date of Conversion of Paul the Apostle which the New Testament accounts place some time after the death of Jesus.[13][14][15] Paul's conversion is discussed in both the Letters of Paul and in the Acts of the Apostles.[13][82]

In the First Epistle to the Corinthians (15:3-8), Paul refers to his conversion. The Acts of the Apostles includes three separate references to his conversion experience, in Acts 9, Acts 22 and Acts 26.[83][84]

Estimating the year of Paul's conversion relies on working backwards from his trial before Junius Gallio in Achaea Greece (Acts 18:12-17) around AD 51–52, a date derived from the discovery and publication, in 1905, of four stone fragments as part of the Delphi Inscriptions, at Delphi across the Gulf from Corinth.[81][85] The inscription[86] preserves a letter from Claudius concerning Gallio dated during the 26th acclamation of Claudius, sometime between January 51 and August 52.[87]

On this basis, most historians estimate that Gallio (brother of Seneca the Younger) became proconsul between the spring of AD 51 and the summer of AD 52, and that his position ended no later than AD 53.[80][81][85][88][89] The trial of Paul is generally assumed to be in the earlier part of Gallio's tenure, based on the reference (Acts 18:2) to his meeting in Corinth with Priscilla and Aquila, who had been recently expelled from Rome based on Emperor Claudius' expulsion of Jews from Rome, which is dated to AD 49-50.[85][90]

According to the New Testament, Paul spent eighteen months in Corinth, approximately seventeen years after his conversion.[81][91] Galatians 2:1-10 states that Paul went back to Jerusalem fourteen years after his conversion, and various missions (at times with Barnabas) such as those in Acts 11:25-26 and 2 Corinthians 11:23-33 appear in the Book of Acts.[13][14] The generally accepted scholarly estimate for the date of conversion of Paul is AD 33-36, placing the death of Jesus before this date range.[13][14][15]

Astronomical analysis

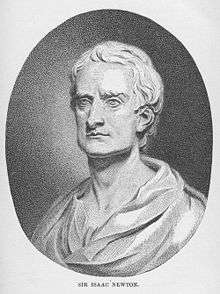

Newton's method

All four Gospels agree to within about a day that the crucifixion was at the time of Passover, and all four Gospels agree that Jesus died a few hours before the commencement of the Jewish Sabbath, i.e. he died before nightfall on a Friday (Matt 27:62, 28:1, Mark 15:42, Luke 23:54, John 19:31,42). The consensus of modern scholarship agrees that the New Testament accounts represent a crucifixion occurring on a Friday, although a Wednesday crucifixion has also been proposed.[92][93] In the official festival calendar of Judaea, as used by the priests of the temple, Passover time was specified precisely. The slaughtering of the lambs for Passover occurred between 3pm and 5pm on the 14th day of the Jewish month Nisan (corresponding to March/April in our calendar). The Passover meal commenced at moonrise (necessarily a full moon) that evening, i.e., at the start of 15 Nisan (the Jewish day running from evening to evening) (Leviticus 23 v. 5; Numbers 28 v. 16). There is an apparent discrepancy of one day in the Gospel accounts of the crucifixion which has been the subject of considerable debate. In John's Gospel, it is stated that the day of Jesus' trial and execution was the day before Passover (John 18 v. 28 and 19 v. 14), Hence John places the crucifixion on 14 Nisan. The correct interpretation of the Synoptics is less clear. Thus some scholars believe that all 4 Gospels place the crucifixion on Friday, 14 Nisan, others believe that according to the Synoptics it occurred on Friday, 15 Nisan. The problem that then has to be solved is that of determining in which of the years of the reign of Pontius Pilate (AD 26-36) the 14th and 15th Nisan fell on a Friday.[94]

In 1733, Isaac Newton considered only the range AD 31-36 and calculated that the Friday requirement is met only on Friday 3 April AD 33, and 23 April AD 34. The latter date can only have fallen on a Friday if an exceptional leap month had been introduced that year, but this was favoured by Newton.[95][96][97][98] In the twentieth century, the standard view became that of J. K. Fotheringham, who in 1910 suggested 3 April AD 33 on the basis of its coincidence with a lunar eclipse.[97][99] In the 1990s Bradley E. Schaefer and J. P. Pratt, following a similar method, arrived at the same date.[96][100] Also according to Humphreys and Waddington, the lunar Jewish calendar leaves only two plausible dates within the reign of Pontius Pilate for Jesus' death, and both of these would have been a 14 Nisan as specified in the Gospel of John: Friday 7 April AD 30, and Friday 3 April AD 33.

The difficulty here is that the Jewish calendar was based not on astronomical calculation but on observation. It is possible to establish the phase of the moon on a particular day two thousand years ago but not whether it was obscured by clouds or haze.[101][102] Including the possibility of a cloudy sky obscuring the moon, and assuming that the Jewish authorities would be aware that lunar months can only be either 29 or 30 days long (the time from one new moon to the next is 29.53 days), then the Friday requirement might also have been met, during Pontius Pilate's term of office, on 11 April AD 27. Another potential date arises if the Jewish authorities happened to add an irregular lunar leap month to compensate for a meteorologically delayed harvest season: this would yield one additional possibility during Pilate's time, which is Newton's favoured date of 23 April AD 34.[103] Colin Humphreys calculates but rejects these AD 27 and AD 34 dates on the basis that the former is much too early to be compatible with Luke 3:1-2, and spring AD 34 is probably too late to be compatible with Paul's timeline.[104]

Eclipse method

A lunar eclipse is potentially alluded to in Acts of the Apostles 2:14-21 ("The sun shall be turned into darkness, And the moon into blood, Before the day of the Lord come"), as pointed out by physicist Colin Humphreys and astronomer Graeme Waddington. There was in fact a lunar eclipse on 3 April AD 33,[99] a date which coincides with one of Newton's astronomically possible crucifixion dates (see above). Humphreys and Waddington have calculated that in ancient Jerusulem this eclipse would have been visible at moonrise at 6.20pm as a 20% partial eclipse (a full moon with a potentially red "bite" missing at the top left of the moon's disc). They propose that a large proportion of the Jewish population would have witnessed this eclipse as they would have been waiting for sunset in the west and immediately afterwards the rise of the anticipated full moon in the east as the prescribed signal to start their household Passover meals.[94] Humphreys and Waddington therefore suggest a scenario where Jesus was crucified and died at 3pm on 3 April AD 33, followed by a red partial lunar eclipse at moonrise at 6.20pm observed by the Jewish population, and that Peter recalls this event when preaching the resurrection to the Jews (Acts of the Apostles 2:14-21).[94] Astronomer Bradley Schaefer agrees with the eclipse date but disputes that the eclipsed moon would have been visible by the time the moon had risen in Jerusalem.[105][106][107]

A potentially related issue involves the reference in the Synoptic Gospels to a three-hour period of darkness over the whole land on the day of the crucifixion (according to Luke 23:45 τοῦ ἡλίου ἐκλιπόντος - the sun was darkened). Although some scholars view this as a literary device common among ancient writers rather than a description of an actual event,[108][109] other writers have attempted to identify a meteorological event or a datable astronomical phenomenon which this could have referred to. It could not have been a solar eclipse, since this could not take place during the crucifixion at Passover,[110][111] and in any case solar eclipses take minutes, not hours.[112] In 1983, astronomers Humphreys and Waddington noted that the reference to a solar eclipse is missing in some versions of Luke and argued that the solar eclipse was a later faulty scribal amendment of what was actually the lunar eclipse of AD 33.[18] This is a claim which historian David Henige describes as 'undefended' and 'indefensible'.[113] Humphreys and a number of scholars have alternatively argued for the sun's darkening to have been caused by a khamsin, i.e. a sand storm, which can occur between mid-March and May in the Middle East and which does typically last for several hours.[114]

In a review[115] of Humphreys' book, theologian William R Telford points out that the non-astronomical parts of his lunar eclipse argument are based on the assumption that the chronologies described in the New Testament are historical and based on eyewitness testimony, accepting uncritically statements such as the "three different Passovers in John" and Matthew's statement that Jesus died at the ninth hour. He also notes that Humphreys uses some very dubious sources such as Pilate's alleged letter to Tiberius Caesar.[116]

Double Passover method

In the crucifixion narrative, the synoptic gospels stress that Jesus celebrated a Passover meal (Mark 14:12ff, Luke 22:15) before his crucifixion, which contrasts sharply with the independent gospel of John who is explicit that the official "Jewish" Passover (John 11:55) started at nightfall after Jesus' death. In his 2011 book, Colin Humphreys proposes a resolution to this apparent discrepancy by positing that Jesus' "synoptic" Passover meal in fact took place two days before John's "Jewish" Passover because the former is calculated by the putative original Jewish lunar calendar (itself based on the Egyptian liturgical lunar calendar putatively introduced to the Israelites by Moses in the 13th century BC, and still used today by the Samaritans). The official "Jewish" Passover in contrast was determined by a Jewish calendar reckoning which had been modified during the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BC. This modified Jewish calendar is in use among most Jews today. One basic difference lies in the determination of the first day of the new month: while the Samaritans use the calculated (because by definition invisible) new moon, mainstream Jews use the first observation of the thin crescent of the waxing moon which is on average 30 hours later. The other basic difference lies in the fact that the Samaritan calendar uses a sunrise-to-sunrise day, while the official Jewish calendar uses a sunset-to-sunset day. Due to these differences, the Samaritan Passover is normally one day earlier than the Jewish Passover (and in some years two or more days earlier). The crucifixion year of Jesus can then be calculated by asking the question in which of the two astronomically possible years of AD 30 and AD 33 is there a time gap between the last supper and the crucifixion which is compatible with the gospel timeline of Jesus' last 6 days. The astronomical calculations show that a hypothetical AD 30 date would require an incompatible Monday Last Supper, while AD 33 offers a compatible Last Supper on Wednesday, 1 April AD 33, followed by a compatible crucifixion on Friday, 3 April AD 33.[117]

Given these assumptions he argues that the calculated date of Wednesday 1 April AD 33 for the Last Supper allows all four gospel accounts to be astronomically correct, with Jesus celebrating Passover two days before his death according to the original Mosaic calendar, and the Jewish authorities celebrating Passover just after the crucifixion, using the modified Babylonian calendar. In contrast, the Christian church tradition of celebrating the Last Supper on Maundy Thursday would be an anachronism.[118][119] The calculated chronology incidentally supports John's narrative that Jesus died at the same hour (Friday 3pm) on 3 April AD 33 that the Passover lambs were slaughtered.[120]

In a review of Humphreys' book, theologian William R Telford counters that the separate day schema of the Gospel's Holy Week "is an artificial as well as an inconsistent construction". As Telford had pointed out in his own book in 1980,[121] "the initial three-day structure found in [Mark 11] is occasioned by the purely redactional linkage of the extraneous fig-tree story with the triumphal entry and cleansing of the temple traditions, and is not a chronology upon which one can base any historical reconstructions."

Scholarly debate on time of death

.jpg)

The estimation of the hour of the death of Jesus based on the New Testament accounts has been the subject of debate among scholars for centuries, since there was perceived to be[122] a clear difference between the accounts in the Synoptic Gospels and that in the Gospel of John.

The debate can be summarised as follows. In the Synoptic account, the Last Supper takes place on the first night of Passover, defined in the Torah as occurring after daylight on 14 of Nisan, and the crucifixion is on 15 Nisan.[123] However, in the Gospel of John the trial of Jesus takes place before the Passover meal[124] and the sentencing takes place on the day of Preparation, before Passover. John's account places the crucifixion on 14 Nisan, since the law mandated the lamb had to be sacrificed between 3:00 pm and 5:00 pm and eaten before midnight on that day.[125][126][127] This understanding fits well with Old Testament typology, in which Jesus entered Jerusalem to identify himself as the Paschal lamb on Nisan 10 was crucified and died at 3:00 in the afternoon of Nisan 14, at the same time the High Priest would have sacrificed the Paschal lamb, and rose before dawn the morning of Nisan 16, as a type of offering of the First Fruits. It is problematic to reconcile the chronology presented by John with the Synoptic tradition that the Last Supper was a Passover meal.[128] Some scholars have presented arguments to reconcile the accounts,[129] although Raymond E. Brown, reviewing these, concluded that they can not be easily reconciled.[122] One involves the suggestion that [130] for Jesus and his disciples, the Passover could have begun at dawn Thursday, while for traditional Jews it would not have begun until dusk that same day.[131][132] Another is that John followed the Roman practice of calculating the new day beginning at midnight, rather than the Jewish reckoning.[133] However, this Roman practice was used only for dating contracts and leases.[134][135] D. A. Carson argues that 'preparation of the Passover' could mean any day of the Passover week.[136] Some have argued that the modern precision of marking the time of day should not be read back into the gospel accounts, written at a time when no standardization of timepieces, or exact recording of hours and minutes was available.[129][137] Andreas Köstenberger argues that in the first century time was often estimated to the closest three-hour mark, and that the intention of the author of the Mark Gospel was to provide the setting for the three hours of darkness while the Gospel of John seeks to stress the length of the proceedings, starting in the 'early morning'"[138] William Barclay has argued that the portrayal of the death of Jesus in the John Gospel is a literary construct, presenting the crucifixion as taking place at the time on the day of Passover when the sacrificial lamb would be killed, and thus portraying Jesus as the Lamb of God.[139]

Colin Humphreys' widely publicised "double passover" astronomical analysis, published in 2011 and outlined above, places the hour of death of Jesus at 3pm on 3 April AD 33 and claims to reconcile the Gospel accounts for the "six days" leading up to the crucifixion. His solution is that the synoptic gospels and John's gospel use two distinct calendars (the official Jewish lunar calendar, and what is today the Samaritan lunar calendar, the latter used in Jesus' day also by the Essenes of Qumran and the Zealots). Humphrey's proposal was preceded in 1957 by the work of Annie Jaubert[140] who suggested that Jesus held his Last Supper at Passover time according to the Qumran solar calendar. Humphreys rejects Jaubert's conclusion by demonstrating that the Qumran solar reckoning would always place Jesus' Last Supper after the Jewish Passover, in contradiction to all four gospels. Instead, Humphreys points out that the Essene community at Qumran additionally used a lunar calendar, itself evidently based on the Egyptian liturgical lunar calendar. Humphreys suggests that the reason why his two-calendar solution had not been discovered earlier is (a) widespread scholarly ignorance of the existence of the Egyptian liturgical lunar calendar (used alongside the well-known Egyptian administrative solar calendar, and presumably the basis for the 13th-century BC Jewish lunar calendar), and (b) the fact that the modern surviving small community of Samaritans did not reveal the calculations underlying their lunar calendar (preserving the Egyptian reckoning) to outsiders until the 1960s.

In a review of Humphreys' book, theologian William R Telford points out that the non-astronomical parts of his argument are based on the assumption that the chronologies described in the New Testament are historical and based on eyewitness testimony. In doing so, Telford says, Humphreys has built an argument upon unsound premises which "does violence to the nature of the biblical texts, whose mixture of fact and fiction, tradition and redaction, history and myth all make the rigid application of the scientific tool of astronomy to their putative data a misconstrued enterprise."[115]

Other approaches

Other approaches to the chronology of Jesus have been suggested over the centuries, e.g. Maximus the Confessor, Eusebius, and Cassiodorus asserted that the death of Jesus occurred in AD 31. The 3rd/4th century Roman historian Lactantius states that Jesus was crucified on a particular day in AD 29, but that did not correspond to a full moon.[141]

Some commentators have attempted to establish the date of birth by identifying the Star of Bethlehem with some known astronomical or astrological phenomenon.[142] There are many possible phenomena and none seems to match the Gospel account exactly,[143] although new authors continue to offer potential candidates.[144]

See also

- Historicity and chronology

- Baptism of Jesus

- Timeline of Christianity

- Historical Jesus

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Depiction of Jesus

References

- 1 2 3 4 Dunn, James DG (2003). "Jesus Remembered". Eerdmans Publishing: 324.; D. A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo and Leon Morris. An Introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1992, 54, 56; Michael Grant, Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels, Scribner's, 1977, p. 71.; Ben Witherington III, "Primary Sources," Christian History 17 (1998) No. 3:12–20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible 2000 Amsterdam University Press ISBN 90-5356-503-5 page 249

- 1 2 The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew-Luke, Volume 1 by Craig A. Evans 2003 ISBN 0-7814-3868-3 pages 67-69

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Paul L. Maier "The Date of the Nativity and Chronology of Jesus" in Chronos, kairos, Christos: nativity and chronological studies by Jerry Vardaman, Edwin M. Yamauchi 1989 ISBN 0-931464-50-1 pages 113-129

- 1 2 3 Craig Evans, 2006 "Josephus on John the Baptist" in The Historical Jesus in Context edited by Amy-Jill Levine et al. Princeton Univ Press ISBN 978-0-691-00992-6 pages 55-58

- 1 2 3 4 5 Herodias: at home in that fox's den by Florence Morgan Gillman 2003 ISBN 0-8146-5108-9 pages 25-30

- 1 2 3 4 International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1982 ISBN 0-8028-3782-4 pages 694-695

- 1 2 3 The Riddles of the Fourth Gospel: An Introduction to John by Paul N. Anderson 2011 ISBN 0-8006-0427-X pages 200

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Herod the Great by Jerry Knoblet 2005 ISBN 0-7618-3087-1 page 183-184

- 1 2 J. Dwight Pentecost, The Words and Works of Jesus Christ: A Study of the Life of Christ (Zondervan, 1981) pages 577-578.

- ↑ Funk, Robert W.; Jesus Seminar (1998). The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. San Francisco: Harper.

- ↑ The Word in this world by Paul William Meyer, John T. Carroll 2004 ISBN 0-664-22701-5 page 112

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times by Paul Barnett 2002 ISBN 0-8308-2699-8 pages 19-21

- 1 2 3 4 The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pages 77-79

- 1 2 3 4 Paul's early period: chronology, mission strategy, theology by Rainer Riesner 1997 ISBN 978-0-8028-4166-7 page 19-27 (page 27 has a table of various scholarly estimates)

- 1 2 3 The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 page 114

- 1 2 Sanders (1993). "The Historical Figure of Jesus": 11, 249.

- 1 2 Colin J. Humphreys and W. G. Waddington, The Date of the Crucifixion Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation 37 (March 1985)

- 1 2 Jesus in history, thought, and culture: an encyclopedia, Volume 1 by James Leslie Houlden 2003 ISBN 1-57607-856-6 pages 508-509

- ↑ Brown, Raymond E. (1994). The Death of the Messiah: from Gethsemane to the Grave: A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels. New York: Doubleday, Anchor Bible Reference Library. p. 964. ISBN 978-0-385-19397-9.

- ↑ Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus by Gerald O'Collins 2009 ISBN 0-19-955787-X pages 1-3

- ↑ Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell 1998 ISBN 0-664-25703-8 pages 168-173

- 1 2 Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi by Karl Rahner 2004 ISBN 0-86012-006-6 pages 730-731

- 1 2 Interpreting Gospel Narratives: Scenes, People, and Theology by Timothy Wiarda 2010 ISBN 0-8054-4843-8 pages 75-78

- ↑ Paula Fredriksen, 1999, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, Alfred A. Knopf Publishers, pages=6–7, 105–10, 232–34, 266

- ↑ Matthew by David L. Turner 2008 ISBN 0-8010-2684-9 page 613

- ↑ Sanders, EP (1995). "The Historical Figure of Jesus". London: Penguin Books: 3.

- ↑ Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0-8054-4482-3 pages 431-436

- ↑ In a 2011 review of the state of modern scholarship, Bart Ehrman wrote: "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees" B. Ehrman, 2011 Forged : writing in the name of God ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6. page 285

- ↑ Ramm, Bernard L (1993). "An Evangelical Christology: Ecumenic and Historic". Regent College Publishing: 19.

There is almost universal agreement that Jesus lived

- ↑ Borg, Marcus (1999). "The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions (Ch. 16, A Vision of the Christian Life)". HarperCollins: 236.

some judgements are so probable as to be certain; for example, Jesus really existed

- ↑

- New Testament History by Richard L. Niswonger 1992 ISBN 0-310-31201-9 pages 121-124

- Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi by Karl Rahner 2004 ISBN 0-86012-006-6 page 731

- Nikos Kokkinos, 1998, in Chronos, kairos, Christos 2 by Ray Summers, Jerry Vardaman ISBN 0-86554-582-0 pages 121-126

- Murray, Alexander, "Medieval Christmas", History Today, December 1986, 36 (12), pp. 31 – 39.

- The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 page 114

- Hoehner, Harold W (1978). Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ. Zondervan. pp. 29–37. ISBN 0-310-26211-9.

- Jack V. Scarola, "A Chronology of the nativity Era" in Chronos, kairos, Christos 2 by Ray Summers, Jerry Vardaman 1998 ISBN 0-86554-582-0 pages 61-81

- Christianity and the Roman Empire: background texts by Ralph Martin Novak 2001 ISBN 1-56338-347-0 pages 302-303

- ↑ Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, Charles L Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown (B&H Publishing, 2009), page 139-140.

- ↑ Luke 1-5: New Testament Commentary by John MacArthur 2009 ISBN 0-8024-0871-0 page 201

- ↑ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, page 64

- 1 2 3 4 The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pages 140-141

- ↑ Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0-8054-4482-3 page 224-229

- ↑ Christianity: an introduction by Alister E. McGrath 2006 ISBN 978-1-4051-0901-7 pages 16-22

- ↑ Who is Jesus?: an introduction to Christology by Thomas P. Rausch 2003 ISBN 978-0-8146-5078-3 page

- 1 2 The building program of Herod the Great by Duane W. Roller 1998 University of California Press ISBN 0-520-20934-6 pages 67-71

- 1 2 The Temple of Jerusalem: past, present, and future by John M. Lundquist 2007 ISBN 0-275-98339-0 pages101-103

- ↑ The biblical engineer: how the temple in Jerusalem was built by Max Schwartz 2002 ISBN 0-88125-710-9 pages xixx-xx

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the historical Jesus by Craig A. Evans 2008 ISBN 0-415-97569-7 page 115

- ↑ Andreas J. Köstenberger, John (Baker Academic, 2004), page 110.

- ↑ Jesus in Johannine tradition by Robert Tomson Fortna, Tom Thatcher 2001 ISBN 978-0-664-22219-2 page 77

- ↑ The new complete works of Josephus by Flavius Josephus, William Whiston, Paul L. Maier ISBN 0-8254-2924-2

- ↑ Ant 18.5.2-4

- ↑ Women in scripture by Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross Shepard Kraemer 2001 ISBN 0-8028-4962-8 pages 92-93

- ↑ Herod Antipas in Galilee: The Literary and Archaeological Sources by Morten H. Jensen 2010 ISBN 978-3-16-150362-7 pages 42-43

- 1 2 The Emergence of Christianity: Classical Traditions in Contemporary Perspective by Cynthia White 2010 ISBN 0-8006-9747-2 page 48

- ↑ ''Herod Antipas'' by Harold W. Hoehner'' 1983 ISBN 0-310-42251-5 page 131. Books.google.com. 1983-01-28. ISBN 9780310422518. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- ↑ The relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth by Daniel S. Dapaah 2005 ISBN 0-7618-3109-6 page 48

- 1 2 Herod Antipas by Harold W. Hoehner 1983 ISBN 0-310-42251-5 pages 125-127

- ↑ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A-D by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1995 ISBN 0-8028-3781-6 pages 686-687

- ↑ Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1995), International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. vol. K-P. p. 929.

- ↑ Matthew 27:27-61, Mark 15:1-47, Luke 23:25-54 and John 19:1-38

- 1 2 Theissen 1998, pp. 81-83

- ↑ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 page 104-108

- ↑ Evans, Craig A. (2001). Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies ISBN 0-391-04118-5 page 316

- ↑ Wansbrough, Henry (2004). Jesus and the oral Gospel tradition ISBN 0-567-04090-9 page 185

- ↑ James Dunn states that there is "broad consensus" among scholars regarding the nature of an authentic reference to the crucifixion of Jesus in the Testimonium.Dunn, James (2003). Jesus remembered ISBN 0-8028-3931-2 page 141

- ↑ Skeptic Wells also states that after Shlomo Pines' discovery of new documents in the 1970s scholarly agreement on the authenticity of the nucleus of the Tetimonium was achieved, The Jesus Legend by G. A. Wells 1996 ISBN 0812693345 page 48: "... that Josephus made some reference to Jesus, which has been retouched by a Christian hand. This is the view argued by Meier as by most scholars today particularly since S. Pines..." Josephus scholar Louis H. Feldman views the reference in the Testimonium as the first reference to Jesus and the reference to Jesus in the death of James passage in Book 20, Chapter 9, 1 of the Antiquities as "the aforementioned Christ", thus relating the two passages.Feldman, Louis H.; Hata, Gōhei, eds. (1987). Josephus, Judaism and Christianity ISBN 978-90-04-08554-1 page 55

- ↑ Van Voorst, Robert E (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence Eerdmans Publishing ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 pages 39-42

- ↑ Backgrounds of early Christianity by Everett Ferguson 2003 ISBN 0-8028-2221-5 page 116

- 1 2 Green, Joel B. (1997). The Gospel of Luke : new international commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. p. 168. ISBN 0-8028-2315-7.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 18.89.

- ↑ Pontius Pilate: portraits of a Roman governor by Warren Carter 2003 ISBN 0-8146-5113-5 pages 44-45

- ↑ The history of the Jews in the Greco-Roman world by Peter Schäfer 2003 ISBN 0-415-30585-3 page 108

- ↑ Backgrounds of early Christianity by Everett Ferguson 2003 ISBN 0-8028-2221-5 page 416

- 1 2 New Testament History by Richard L. Niswonger 1992 ISBN 0-310-31201-9 page 172

- 1 2 Pontius Pilate: portraits of a Roman governor by Warren Carter 2003 ISBN 978-0-8146-5113-1 pages 120-121

- ↑ The Synoptics: Matthew, Mark, Luke by Ján Majerník, Joseph Ponessa 2005 ISBN 1-931018-31-6 page 181

- ↑ The Gospel according to Luke by Michael Patella 2005 ISBN 0-8146-2862-1 page 16

- ↑ Luke: The Gospel of Amazement by Michael Card 2011 ISBN 978-0-8308-3835-6 page 251

- ↑ "Bible Study Workshop - Lesson 228" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- ↑ Herod Antipas by Harold W. Hoehner 1983 ISBN 0-310-42251-5 page 262

- ↑ All the people in the Bible by Richard R. Losch 2008 ISBN 0-8028-2454-4 page 159

- ↑ The Content and the Setting of the Gospel Tradition by Mark Harding, Alanna Nobbs 2010 ISBN 0-8028-3318-7 pages 88-89

- ↑ The Emergence of Christianity by Cynthia White 2010 ISBN 0-8006-9747-2 page 11

- 1 2 The Cambridge Companion to St Paul by James D. G. Dunn (Nov 10, 2003) Cambridge Univ Press ISBN 0521786940 page 20

- 1 2 3 4 Paul: his letters and his theology by Stanley B. Marrow 1986 ISBN 0-8091-2744-X pages 45-49

- ↑ Bromiley, Geoffrey William (1979). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A-D Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 689. ISBN 0-8028-3781-6.

- ↑ Paul and His Letters by John B. Polhill 1999 ISBN 0-8054-1097-X pages 49-50

- ↑ The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology by William Lane Craig, James Porter Moreland 2009 ISBN 1-4051-7657-1 page 616

- 1 2 3 Christianity and the Roman Empire: background texts by Ralph Martin Novak 2001 ISBN 1-56338-347-0 pages 18-22

- ↑ "The Gallio Inscription". Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ↑ John B. Polhill, Paul and His Letters, B&H Publishing Group, 1999, ISBN 9780805410976, p.78.

- ↑ The Greco-Roman world of the New Testament era by James S. Jeffers 1999 ISBN 0-8308-1589-9 pages 164-165

- ↑ The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Acts-Philemon by Craig A. Evans 2004 ISBN 0-7814-4006-8 page 248

- ↑ The Bible Knowledge Commentary: New Testament edition by John F. Walvoord, Roy B. Zuck 1983 ISBN 0-88207-812-7 page 405

- ↑ Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible Amsterdam University Press, 2000 ISBN 90-5356-503-5 page 1019

- ↑ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pages 142–143

- ↑ New Testament History by Richard L. Niswonger 1992 ISBN 0-310-31201-9 pages 167–168

- 1 2 3 "The Date of the Crucifixion", Colin Humphreys and W. Graeme Waddington, March 1985. American Scientific Affiliation website. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑

- 1 2 Pratt, J. P. (1991). "Newton's Date for the Crucifixion". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 32 (3): 301–304. Bibcode:1991QJRAS..32..301P.

- 1 2 Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, pages 45-48

- ↑ Newton, Isaac (1733). "Of the Times of the Birth and Passion of Christ", in Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John

- 1 2 Fotheringham, J.K., 1910. "On the smallest visible phase of the moon," Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 70, 527-531; "Astronomical Evidence for the Date of the Crucifixion," Journal of Theological Studies (1910) 12, 120-127'; "The Evidence of Astronomy and Technical Chronology for the Date of the Crucifixion," Journal of Theological Studies (1934) 35, 146-162.

- ↑ Schaefer, B. E. (1990). "Lunar Visibility and the Crucifixion". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 31 (1): 53–67. Bibcode:1990QJRAS..31...53S.

- ↑ C. Philipp E. Nothaft, Dating the Passion: The Life of Jesus and the Emergence of Scientific Chronology (200–1600) page 25.

- ↑ E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus (Penguin, 1993) 285-286.

- ↑ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, pages 53-58

- ↑ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, pages 63-66

- ↑ Schaefer, B. E. (1990, March). Lunar visibility and the crucifixion. Royal Astronomical Society Quarterly Journal, 31(1), 53-67

- ↑ Schaefer, B. E. (1991, July). Glare and celestial visibility. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 103, 645-660.

- ↑ Marking time: the epic quest to invent the perfect calendar by Duncan Steel 1999 ISBN 0-471-29827-1 page 341

- ↑ David E. Garland, Reading Matthew: A Literary and Theological Commentary on the First Gospel (Smyth & Helwys Publishing, 1999) page 264.

- ↑ Geza Vermes, The Passion (Penguin, 2005) page 108-9.

- ↑ Exploring Ancient Skies: A Survey of Ancient and Cultural Astronomy by David H. Kelley, Eugene F. Milone 2011 ISBN 1-4419-7623-X pages 250-251

- ↑ Astronomy: The Solar System and Beyond by Michael A. Seeds, Dana Backman, 2009 ISBN 0-495-56203-3 page 34

- ↑ Meeus, J. (2003, December). The maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse. Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 113(6), 343-348.

- ↑ Henige, David P. (2005). Historical evidence and argument. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-299-21410-4.

- ↑ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, page 84-85

- 1 2 Telford, William R. (2015). "Review of The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus". The Journal of Theological Studies. 66 (1): 371–376. doi:10.1093/jts/flv005. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ Humphreys 2011 p85 "Much apocryphal writing consists of highly theatrical literature, which cannot be used as historical evidence ... if [Pilate's report to Tertullian] is a Christian forgery, probably made up on the basis of Acts, as seems likely, then this suggests there was a tradition that at the crucifixion the moon appeared like blood."

- ↑ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, page 164

- ↑ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, page 37

- ↑ Staff Reporter (18 April 2011). "Last Supper was on Wednesday, not Thursday, challenges Cambridge professor Colin Humphreys.". International Business Times. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, page 192-195

- ↑ WR Telford The Barren Temple and the Withered Tree: A Redaction-Critical Analysis of the Cursing of the Fig-Tree Pericope in Mark's Gospel and its Relation to the Cleansing of the Temple Tradition Bloomsbury, London, 1980

- 1 2 Death of the Messiah, Volume 2 by Raymond E. Brown 1999 ISBN 0-385-49449-1 pages 959-960

- ↑ Lev 23:5-6

- ↑ Paul Barnett, Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times, page 21 (InterVarsity Press, 1999). ISBN 978-0-8308-2699-5

- ↑ Philo. "De Specialibus Legibus 2.145".

- ↑ Josephus. The War of the Jews 6.9.3

- ↑ Mishnah, Pesahim 5.1.

- ↑ Matthew 26:17-19; Mark 14:12-16; Luke 22:7-8

- 1 2 Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 pages 323-323

- ↑ Stroes, H. R. (October 1966). "Does the Day Begin in the Evening or Morning? Some Biblical Observations". Vetus Testamentum. BRILL. 16 (4): 460–475. doi:10.2307/1516711. JSTOR 1516711.

- ↑ Ross, Allen. "Daily Life In The Time Of Jesus".

- ↑ Hoehner, Harold (1977). Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- ↑ Brooke Foss Westcott, The Gospel according to St. John : the authorised version with introduction and notes (1881, page 282).

- ↑ Hunt, Michal - The Passover Feast and Christ's Passion - Copyright © 1991, revised 2007 - Agape Bible Study. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ Leon Morris - The New International Commentary on the New Testament - The Gospel According to John (Revised) - William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan/Cambridge, U.K. - 1995, pages 138 and 708.

- ↑ D.A. Carson, 'The Gospel According to John', Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 1991, p604

- ↑ New Testament History by Richard L. Niswonger 1992 ISBN 0-310-31201-9 pages 173-174

- ↑ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 page 538

- ↑ William Barclay (2001). The Gospel of John. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-61164-015-1.

- ↑ La date de la cène, Gabalda, Paris

- ↑ Lactantius, Of the Manner In Which the Persecutors Died 2: "In the latter days of the Emperor Tiberius, in the consulship of Ruberius (sic) Geminus and Fufius Geminus, and on the tenth of the kalends of April, as I find it written".

- ↑ For example, astronomer Michael Molnar identified April 17, 6 BC as the likely date of the Nativity, since that date corresponded to the heliacal rising and lunar occultation of Jupiter, while it was momentarily stationary in the sign of Aries; according to Molnar, to knowledgeable astrologers of this time, this highly unusual combination of events would have indicated that a regal personage would be (or had been) born in Judea. Michael R. Molnar, "The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi," Rutgers University Press, 1999.

- ↑ Raymond E. Brown, 101 Questions and Answers on the Bible, Paulist Press (2003), page 79.

- ↑ A recent example points back to a 1991 report from the Royal Astronomical Society, which mentions that Chinese astronomers noted a "comet" that lasted 70 days in the Capricorn region of the sky, in March of 5 BC. Authors Dugard and O'Reilly point to this event as the likely Star of Bethlehem. O'Reilly, Bill, and Dugard, Martin, "Killing Jesus: A History," Henry Holt and Company, 2013, ISBN 0805098542, page 15.