Assyrian Church of the East

Assyrian Church of the East (ACOE) ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ ܕܐܬܘܖ̈ܝܐ (Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East) | |

|---|---|

|

Emblem of the Assyrian Church of the East | |

| Founder | Traces origins to Thomas the Apostle, Bartholomew the Apostle, Thaddeus of Edessa and Saint Mari. |

| Independence | Apostolic Age |

| Recognition | Council of Ephesus |

| Primate | Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East, Gewargis III |

| Headquarters | Erbil, Iraq |

| Territory | Iraq, Iran, Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, India, United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Austria, Germany, Russia, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, Italy, Georgia, Armenia, Oceania. |

| Possessions | — |

| Language | Syriac,[1] Aramaic |

| Members | 170,000–500,000[2][3] |

| Website | Holy Apostolic Assyrian Church of the East Official News Website |

The Assyrian Church of the East (Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ ܕܐܬܘܖ̈ܝܐ ʻĒdtā d-Madenḥā d-Ātorāyē), officially the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East[4] (Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܩܕܝܫܬܐ ܘܫܠܝܚܝܬܐ ܩܬܘܠܝܩܝ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ ܕܐܬܘܖ̈ܝܐ, ʻEdtā Qaddīštā wa-Šlīḥāitā Qātolīqī d-Madenḥā d-Ātorāyē), is a Syriac Church historically centred in Assyria, northern Mesopotamia, an area which is today encompassed by northern Iraq, north eastern Syria, south eastern Turkey and north western Iran. It is one of the churches that claim continuity with the historical Patriarchate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon – the Church of the East, and the only one which still adheres to the church of the Easts Christology and Nestorian Doctrine. Unlike most other churches that trace their origins to antiquity, the modern Assyrian Church of the East is not in communion with any other churches, either Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholic or Protestant. However, The Chaldean Catholic Church, an offshoot of the Assyrian Church of the East, broke off from them between the 1660s and 1830 to join the Catholic Church, and the Ancient Church of the East split from them in the 1960s. Both of these churches' members are ethnic Assyrians.

Theologically, the church is associated with the doctrine of Nestorianism, leading to the church also being known somewhat inaccurately as a "Nestorian Church", though church leadership has at times rejected the Nestorian label, and the church was already in existence in Assyria some four centuries prior to Nestorius.

The church employs the Syriac dialect of Eastern Aramaic, which first evolved in Assyria during the 5th century BC in its liturgy, the East Syrian Rite, which includes three anaphoras, attributed to Thaddeus (Addai) and Mari, Theodore of Mopsuestia and later also Nestorius.[5]

The Church of the East developed between the first and third centuries from the early Assyrian Christian communities in the Parthian Empire's province of Mesopotamia and the Sasanian province of Asōristān (Assyria) and the small independent Neo-Assyrian kingdoms of Osroene, Adiabene, Beth Garmai, Beth Nuhadra and Assur. At its height, the Church had spread from its heartland in Upper Mesopotamia to as far afield as China, Mongolia, Central Asia, Asia Minor, the Arabian peninsula and India.

A dispute over patriarchal succession led to the Schism of 1552, resulting in there being two rival Patriarchs. One of the two factions (that of the Shimun line) that emerged from this split temporarily joined the Catholic Church by entering into communion with the Latin Church's Holy See so their leader Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa could be ordained as Patriarch by the Pope, forming the short lived Church of Athura (Assyria) and Mosul, but after leaving the Catholic Church in 1660 and readopting their original Assyrian Church doctrines they ended up becoming the only non affiliated line after another rival faction broke away, forming the Vatican named Chaldean Catholic Church in 1830, and therefore the Shimun line in-effect became the modern day Assyrian Church of the East, despite initially leaving it in 1552.[6]

A more recent schism in the church resulted from the adoption of the Gregorian calendar by the Assyrian Church of the East, rather than maintaining the traditional Julian calendar. The opponents to the reforms created the Ancient Church of the East in 1964, headquartered in Baghdad and headed since 1968 by a separate Catholicos-Patriarch.

The Assyrian Church of the East was headed by the Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East, and, after the church hierarchy fled Iraq during the Iran–Iraq War, has resided in Chicago. In terms of hierarchy, below the Catholicos-Patriarch are a number of metropolitan bishops, then diocesan bishops, then priests, and then deacons who serve dioceses and parishes throughout the Middle East, India, North America, Oceania, and Europe (which includes the Caucasus and Russia).

History

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Liturgy and worship |

|

Early years of the Church of the East

The Church of the East originally developed among the Assyrians during the first century AD in Assyria, Upper Mesopotamia and northwestern Persia (today's northern Iraq, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria and northwestern Iran) to the east of the Byzantine Empire – areas where the Assyrian people spoke Mesopotamian Eastern Aramaic languages. It is an Apostolic church established by Thomas the Apostle, Thaddeus of Edessa, and Bartholomew the Apostle. Saint Peter, chief of the apostles, added his blessing to the Church of the East at the time of his visit to the See at Babylon in the earliest days of the church when stating, "The elect church which is in Babylon, salutes you; and Mark, my son." (1 Peter 5:13).[7]

Although founded in the 1st century, the Church first achieved official state recognition from the Sassanid Empire in the fourth century with the accession of Yazdegerd I (reigned 399–420) to the throne of the Sasanian Empire. In 410 the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, held at the Sasanian capital, allowed the Church's leading bishops to elect a formal Catholicos (leader). Catholicos Isaac was required both to lead the Assyrian Christian community, and to answer on its behalf to the Sasanian emperor.[8][9]

Under pressure from the Sasanian Emperor, the Church of the East sought to increasingly distance itself from the Greek Orthodox Church(At the time being known as the church of the Eastern Roman Empire). Therefore, In 424, the bishops of the Sasanian Empire met in council under the leadership of Catholicos Dadishoʿ (421–456) and determined that they would not, henceforth, refer disciplinary or theological problems to any external power, and especially not to any bishop or Church Council in the Roman Empire.[10]

Thus, the Mesopotamian churches did not send representatives to the various Church Councils attended by representatives of the "Western" Church. Accordingly, the leaders of the Church of the East did not feel bound by any decisions of what came to be regarded as Roman Imperial Councils. Despite this, the Creed and Canons of the First Council of Nicaea of 325, affirming the full divinity of Christ, were formally accepted at the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.[11] The Church's understanding of the term hypostasis differs from the definition of the term offered at the Council of Chalcedon of 451. For this reason, the Assyrian Church has never approved the Chalcedonian definition.[11]

The theological controversy that followed the Council of Ephesus in 431 proved a turning point in the Church's history. The Council condemned as heretical the Christology of Nestorius, whose reluctance to accord the Virgin Mary the title Theotokos "God-bearer, Mother of God" was taken as evidence that he believed two separate persons (as opposed to two united natures) to be present within Christ. (For the theological issues at stake, see Assyrian Church of the East and Nestorianism.)

The Sasanian Emperor, hostile to the Byzantines, saw the opportunity to ensure the loyalty of his Christian subjects and lent support to the Nestorian Schism. The Emperor took steps to cement the primacy of the Nestorian party within the Assyrian Church of the East, granting its members his protection,[12] and executing the pro-Roman Catholicos Babowai in 484, replacing him with the Nestorian Bishop of Nisibis, Barsauma. The Catholicos-Patriarch Babai (497–503) confirmed the association of the Assyrian Church with Nestorianism.

Eastern expansion

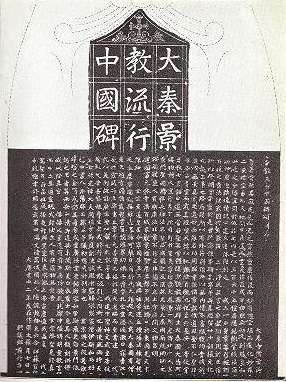

After this split with the Western World and adoption of Nestorianism, The Assyrian Church of the East expanded rapidly due to missionary works during the Medieval period. During the period between 500–1400 the geographical horizons of the Church of the East extended well beyond its heartland in present-day northern Iraq, north eastern Syria and south eastern Turkey. Communities sprang up throughout Central Asia, and missionaries from Assyria and Mesopotamia took the Christian faith as far as China, with a primary indicator of their missionary work being the Nestorian Stele, a Christian tablet written in Chinese script found in China dating to 781 AD. Their most important conversion, however, was of the Saint Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast in India, as they are now the largest group of non ethnically Assyrian Christians on earth, with around 10 million followers when all denominations are added together and their own diaspora is included.[13] The St Thomas Christians were believed by tradition to have been converted by St Thomas, and were in communion with the Church of the East until the end of the medieval period.[14]

Schism and the establishment of the Chaldean Church

The end to the Churches expansion came in 1400, when the massacres of Christians by Timur (1336–1405) destroyed many bishoprics, including the ancient Assyrian city and cultural capital of Ashur and from Tkrit, and the complete the eradication of Christians from much of central and southern Mesopotamia/Iraq.

Due to this disaster, The Church of the East, which had previously extended as far as China, was largely reduced to an Assyrian Neo-Aramaic-speaking remnant living in its original heartland in Upper Mesopotamia.[15](With the exception of the St Thomas Christians in India) The Assyrian churches area of influence was from this point up until the Assyrian genocide a triangular area between Amid (modern Diyarbakır), Mêrdîn (modern Mardin and Edessa to the west, Salmas to the east, Hakkari and Harran to the north, and Mosul, Kirkuk and Arbela (modern Erbil) to the south, essentially a region comprising in modern terms northern Iraq, south east Turkey, north east Syria and the north western fringe of Iran.

Due to the destruction of Assur, The See was moved to the Assyrian town of Alqosh (Kara Akosh) during the 1400s, and Shimun IV Basidi (1437–1493) was appointed Patriarch, establishing a new, hereditary line of succession.[16]

Growing dissent in the church's hierarchy over hereditary succession came to a head in however 1552, when a group of bishops from the northern regions of Amid and Salmas elected Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa as a rival Patriarch. Seeking consecration as Patriarch by a Metropolitan bishop, Sulaqa traveled to Rome in 1553 and entered into communion with the Catholic Church. On being appointed Patriarch, Sulaqa took the name Shimun VIII and was granted the title of "Patriarch of Mosul and Athur". Later under the Josephite branch, this title became "Patriarch of the Chaldeans" and its followers were then dubbed as "Chaldean Christians", despite none of its adherents even being from the long extinct Chaldean tribes of what had long ago been Chaldea in a far off region in southeastern Mesopotamia.[17]

After going to Rome to get communion and be recognized as Patriarch, Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa returned to the Near East the same year, establishing his seat in Amid. However, some time later he was put to death by partisans of the rival Patriarch of Alqosh. Nevertheless, He ordained five metropolitan bishops, thus establishing a new ecclesiastical hierarchy, and a line of patriarchal descent known as "the Shimun line".

Sees in Qochanis, Amid, and Alqosh (17th century)

After establishing the new Catholic-aligned Church of Assyria and Mosul in Amid, Relations with Rome gradually weakened under Shimun VIII's successors. The last of this line of Patriarchs to even be formally recognized by the Pope died in the early 1600s, hereditary accession to the office of Patriarch was reintroduced, and therefore by 1660 the Church of Assyria and Mosul unofficially broke off from the Catholic Church and readopted the doctrines of the Assyrian Church of the East, yet kept its independence as an independent church- dividing the Church of the East into two Patriarchates; the Eliya line, based in Alqosh (comprising that portion of the faithful which had never entered into Communion with Rome), and the Shimun line in Amida.

In 1672, the then Patriarch of the Shimun line, Shimun XIII Dinkha, moved his seat away from Amid to the Assyrian village of Qodchanis (modern Konak, Hakkari) in the mountains of Hakkari. Then In 1692, the Patriarch formally broke communion with Rome and resumed relations with the Eliya line at Alqosh, though still retained the independent structure and jurisdiction of his line of succession. The Assyrians of this region functioned under a Tribal confederation, with each tribe being headed by a Malik, and each Malik was subservient to the Patriarch, who was subservient to the Ottomans.[18]

However, around the same time the Shimun line broke off from the Catholic Church, A new Catholic Patriarchate was formed in 1672 under the name of the Chaldean Catholic Church when Joseph I, the Assyrian Church of the East metropolitan bishop of Amida, entered into communion with Rome, thus separating from the Patriarchal See of Alqosh. In 1681, the Holy See granted Joseph the title of "Patriarch of the Chaldeans deprived of its Patriarch", thus forming a third Patriarchate in the region. At this point there was now the Eliya line in Alqosh, The Shimun line in Quodchanis, and now a Josephite line in Amid. The Eliya and Shimun lines were Nestorian, and the Josephite line was Chaldean.

Chaldean "Josephite" line of Amid

Each of Joseph I's successors took the name Joseph. The Josephite branch had many issues however; stricken early on with internal dissent, the Patriarchiate later struggled with financial difficulties due to the Jizya imposed by the Ottoman authorities upon Christian subjects.

Later on, Yohannan VIII Hormizd, the last of the Eliya line of the Assyrian Church of the East in Alqosh, made a Catholic profession of faith in 1780. Though entering into full communion with the Roman See by 1804, he was not recognized as Patriarch by the Pope until 1830, as the Josephite branch was considered the only legitimate Chaldean Church. However, After the end of the Josephite branch, the Alqosh branch of the Church of the East joined the Chaldean Josephite line based in Amida, thus forming the modern Chaldean Catholic Church, and even to this day a significant portion of the Nineveh plains region is Chaldean Catholic due to this.

So that made the Shimun line of Patriarchs, based in Qodchanis, the only Eastern Church to still remain independent, and it refused to enter communion with Rome or join the so-called Chaldean Church. The Patriarchate of the present-day Assyrian Church of the East, with its see in Erbil, is the continuation of this line.[19]

20th century

After all the tragedies and schisms which thinned the church out, no other was as severe as the Assyrian genocide. At this point the Church of the East was based in the mountains of Hakkari, and had been since 1681. During 1915 The Young Turks invaded the region despite their plea of neutrality during the Caucasus Campaign by Russia and their Armenian allies out of fear of an Assyrian independence movement. In response to this, Assyrians of all denominations (Assyrian Church, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church and Assyrian Protestants) entered into a war of independence and allied themselves with the United Kingdom, the Russian Empire and the Armenians against the Ottomans and their Muslim Kurdish, Iranian and Arab allies. Despite the odds, the Assyrians fought successfully against the Ottomans and their allies for three years throughout south eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, north western Iran and north eastern Syria until they were abandoned by their allies, the Russian Empire and the First Republic of Armenia, due to the Russian Revolution and the collapse of the Armenian defense, leaving the Assyrians vastly outnumbered, surrounded, and cut off from supplies of ammunition and food. During this period their See at Qodchanis was completely destroyed, and the Turks and their Muslim allies massacred all of the Assyrians in the Hakkari mountains. Those who survived fled into Iran with what remained of the Assyrian defense under Agha Petros, where they were pursued into Iranian territory despite the fact they were fleeing. later on in 1918, after the murder of their de facto leader and Patriarch Shimun XXI Benyamin and 150 of his followers during a negotiation, and fearing further massacres at the hands of the Turks and Kurds, most of the survivors fled from Iran into what was to become Iraq by train, seeking protection under the British mandate there, and joined the already existing indigenous Assyrian communities of both Eastern, Orthodox and Catholic rites in the north and formed communities in the cities of Baghdad, Basra, etc.[20]

Assyrians were some of the British Administrations most loyal subjects, and so they employed Assyrian troops ("Iraq Levies") to put down Arab and Kurdish rebellions in the aftermath of World War I and to protect the Turkish and Iranian borders of British Iraq from invasion. In consequence, Assyrians of all Christian denominations endured persecution under the Hashemites, culminating in the Simele massacre in 1933, leading many to flee to the West, in particular to the United States, where Chicago became the centre of the Assyrian–Chaldean–Syriac diaspora. However, the Assyrians who remained continued to work alongside the British, even playing a major role in bringing down the pro-Nazi Iraqi forces during World War II, and remaining attached to British forces until 1955.

Patriarch Shimun XXIII Eshai

During this period the British-educated Patriarch Shimun XXIII Eshai, born into the line of Patriarchs at Qodchanis, agitated for an independent Assyrian state. Following the end of the British mandate in 1933[20] and a massacre of Assyrian civilians at Simele by the Iraqi Army, the Patriarch was forced to take refuge in Cyprus.[21] There, Shimun petitioned the League of Nations regarding his peoples' fate, but to little avail, and he was consequently barred from entering Syria and Iraq. He travelled through Europe before moving to Chicago in 1940 to join the growing Assyrian–Chaldean–Syriac community there.[21]

Due to the Church and the Assyrian community in generals disorganized state as a result of the conflicts of the 20th century, Patriarch Shimun XXIII Eshai was forced to reorganize the church's structure in the United States. He transferred his residence to San Francisco in 1954, and was able to travel to Iran, Lebanon, Kuwait, and India, where he worked to strengthen the church.[22]

In 1964 he decreed a number of changes to the church, including liturgical reform, the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, and the shortening of Lent. These changes, combined with Shimun's long absence from Iraq, caused a rift in the community there which led to another schism. In 1968 traditionalists within the church elected Thoma Darmo as a rival patriarch to Shimun XXIII Eshai, creating the Ancient Church of the East, and based it in Baghdad, Iraq.[23]

In 1972, Shimun decided to step down as Patriarch, and the following year, he married, in contravention to longstanding church custom. This led to a synod in 1973 in which further reforms were introduced, most significantly if which included the permanent abolition of hereditary succession- a practice introduced in the middle of the fifteenth century by the patriarch Shemʿon IV Basidi who had died in 1497); however, it was decided that Shimun should be reinstated. This matter was to be settled at additional synods in 1975, however Shimun was assassinated by an estranged relative before this could take place.[24]

Patriarch Dinkha IV

In 1976, Dinkha IV was elected as Shimun XXIII Eshai's successor. The 33-year-old Dinkha had previously been Metropolitan of Tehran, and operated his see there until the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–1988. Thereafter, Dinkha IV went into exile in the United States, and transferred the patriarchal see to Chicago.[25] Much of his patriarchate had been concerned with tending to the Assyrian–Chaldean–Syriac diaspora community and with ecumenical efforts to strengthen relations with other churches.[25] On 26 March 2015, Dinkha IV died in the United States, leaving the Assyrian Church of the East in a period of sede vacante until 18 September 2015, during which Aprem Mooken served as the custodian of the Patriarchate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.[26][27]

Patriarch Gewargis III

On 18 September 2015, the Holy Synod of the Assyrian Church of the East, elected Gewargis Sliwa, the Metropolitan of Iraq, Jordan and Russia, as Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East to succeed the late Dinkha IV, as Catholicos-Patriarch. On 27 September 2015, he was consecrated as Catholicos-Patriarch in the Cathedral Church of St. John the Baptist, in Erbil. Upon his consecration, he assumed the ecclesiastical name Gewargis III.

Assyrian Church of the East and Nestorianism

The Nestorian nature of Assyrian Christianity remains a matter of contention. Elements of the Nestorian doctrine were explicitly repudiated by Patriarch Dinkha IV on the occasion of his accession in 1976.[28]

The Christology of the Church of the East has its roots in the Antiochene theological tradition of the early Church. The founders of Assyrian theology are Diodorus of Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia, both of whom taught at Antioch. 'Antiochene' is a modern designation given to the style of theology associated with the early Church at Antioch, as contrasted with the theology of the church of Alexandria.[29]

Antiochene theology emphasised Christ's humanity and the reality of the moral choices he faced. In order to preserve the impassibility of Christ's Divine Nature, the unity of His person was defined in a looser fashion than in the Alexandrian tradition.[29] The normative Christology of the Assyrian church was written by Babai the Great (551–628) during the controversy that followed the 431 Council of Ephesus. Babai held that within Christ there exist two γνώμη (essences or hypostases), unmingled, but everlastingly united in the one prosopon(personality).

The precise Christological teachings of Nestorius are shrouded in obscurity. Wary of monophysitism, Nestorius rejected Cyril's theory of a hypostatic union, proposing instead a union of will. Nestorianism has come to mean dyophysitism, in which Christ's dual natures are eternally separate, though it is doubtful whether Nestorius ever taught such a doctrine. Nestorius' rejection of the term Theotokos ('God-bearer', or 'Mother of God') has traditionally been held as evidence that he asserted the existence of two persons – not merely two natures – in Jesus Christ, but there exists no evidence that Nestorius denied Christ's oneness.[30] In the controversy that followed the Council of Ephesus, the term 'Nestorian' was applied to all upholding a strictly Antiochene Christology. In consequence the Church of the East was labelled 'Nestorian', though its theology is not dyophysite.

Ecumenical relations

Pope John XXIII invited many other Christian denominations, including the Assyrian Church of the East, to send "observers" to the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). These observers, graciously received and seated as honored guests right in front of the podium on the floor of the council chamber, did not formally take part in the Council's debate, but they mingled freely with the Catholic bishops and theologians who constituted the council, and with the other observers as well, in the break area during the council sessions. There, cordial conversations began a rapproachment that has blossomed into expanding relations among the Catholic Church, the Churches of the Orthodox Communion led by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, and the ancient churches of the East.

On November 11, 1994, a historic meeting between Dinkha IV and Pope John Paul II took place in Rome. The two patriarchs signed a document titled "Common Christological Declaration Between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East". One side effect of this meeting was that the Assyrian Church's relationship to the fellow Chaldean Catholic Church began to improve.[31]

In 1996, Patriarch Dinkha IV signed an agreement of cooperation with the Chaldean Catholic Church Patriarch of Baghdad, Raphael I Bidawid, in Southfield, Michigan, Bidawid himself being keen to heal theological divisions among Assyrians of all denominations. In 1997, he entered into negotiations with the Syriac Orthodox Church and the two churches ceased anathematizing each other.

The lack of a coherent institution narrative in the Anaphora of Addai and Mari, which dates to apostolic times, has caused many Western Christians, and especially Roman Catholics, to doubt the validity of this anaphora, used extensively by the Assyrian Church of the East, as a prayer of consecration of the eucharistic elements. In 2001, after a study of this issue, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith promulgated a declaration approved by Pope John Paul II stating that this is a valid anaphora. This declaration opened the door to a joint synodal decree officially implementing the present Guidelines for Admission to the Eucharist between the Chaldean Church and the Assyrian Church of the East which the synods of the Assyrian Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church signed and promulgated on 20 July 2001.

This joint synodal decree provides that:

- Assyrian faithful may participate and receive Holy Communion in a Chaldean celebration of the Holy Eucharist

- Chaldean catholic faithful may participate and receive Holy Communion in an Assyrian Church celebration of the Holy Eucharist, even if celebrated using the Anaphora of Addai and Mari in its original form

- Assyrian clergy are invited (but not obliged) to insert the institution narrative into the Anaphora of Addai and Mari when Chaldean faithful are present.

Far from expressing a relationship of full communion between these churches, however, the joint synodal decree actually identifies several issues that require resolution to permit a relationship of full communion.

From a Catholic canonical point of view, provisions of the joint synodal decree are fully consistent with the provisions of canon 671 of the 1991 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, which states: "If necessity requires it or genuine spiritual advantage suggests it and provided that the danger of error or indifferentism is avoided, it is permitted for Catholic Christian faithful, for whom it is physically or morally impossible to approach a Catholic minister, to receive the sacraments of penance, the Eucharist and anointing of the sick from non-Catholic ministers, in whose Churches these sacraments are valid. 3. Likewise Catholic ministers licitly administer the Sacraments of Penance, the Eucharist and Anointing of the Sick to Christian faithful of Eastern Churches, who do not have full communion with the Catholic Church, if they ask for them on their own and are properly disposed." Canons 843 and 844 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law make similar provisions for the Latin Church. The Assyrian Church of the East follows an open communion approach, allowing any baptized Christian to receive its Eucharist after confessing the Real presence of Christ in the Eucharist[32] so there is also no alteration of Assyrian practice. Nonetheless, from an ecumenical perspective, the joint synodal decree marks a major step toward full mutual collaboration of both churches in the pastoral care of their members.

Structure

The Church is governed by an episcopal polity, which is the same as other Catholic churches. The church maintains a system of geographical parishes organized into dioceses and archdioceses. The Catholicos-Patriarch is the head of the church. The Synod comprises Bishops who oversee individual dioceses, and Metropolitans who oversee episcopal dioceses in their territorial jurisdiction.

The Chaldean Syrian Church in India and the Persian Gulf is the largest diocese of the church. Its story goes back to the Church of the East that established presence in Kerala. Connection between the Malabar church and the Church of the East was sporadic for a long period till the arrival of the Portuguese. The church is represented by the Assyrian Church of the East and is in communion with it.

- Hierarchy

The current hierarchy and dioceses is as follows. The Patriarchate of the Church of the East was located since 1681 c in the cathedral church of Mar Shallita, in the village of Qudshanis in the Hakkari mountains of the Ottoman Empire. After the beginning of conflict in 1915, the Patriarchs temporarily resided between Urmia and Salmas, and from 1918 the patriarchs resided in Mosul. After the Simele massacre of 1933, the then Patriarch Shimun XXIII Eshai was exiled to Cyprus due to his agitation for independence. In 1940 he was welcomed to the United States where he set up his residence in Chicago, and administrated the United States and Canada as his Patriarchal province. The patriarchate was then moved to Modesto, California in 1954, and finally to San Francisco in 1958 due to health issues. After the assassination of the Patriarch and the election of Dinkha IV in 1976, the patriarchate was temporarily located in Tehran, where the new patriarch was living at the time. After the Iran–Iraq War and the Iranian Revolution, the Patriarchate again returned to Chicago, where it remained until 2015, when it reestablished itself in the Middle east by organizing in Erbil's Ankawa District after the enstatement of Gewargis III. The Diocese of Eastern United States served as the patriarch's province from 1994 until 2012.

Due to the unstable political, religious and economic situation in the church's historical homeland of the Middle East, many of the church members now reside in Western countries. Churches and dioceses have been established throughout Europe, America and Oceania. The largest expatriate concentration of church members is in the United States, mainly situated in Illinois and California.

Archdioceses

- Archdiosese of India Chaldean Syrian Church – it remains in communion and is the biggest province of the Church with close to 30 active churches, primary and secondary schools, hospitals etc.

- Archdiocese of Iraq and Russia – covers the indigenous territory of the church in Iraq. The archdiocese's territory includes the cities and surroundings of Baghdad, Basra, Kirkuk, and Mosul.

- Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand and Lebanon – Established in October 1984.

Dioceses

- Diocese of Syria – jurisdiction lies throughout all Syria, particularly in the al-Hasakah Governorate, where most of the community reside in al-Hasakah, al-Qamishli and the 35 villages along the Khabur River. There are also small communities in Damascus and Aleppo

- Diocese of Iran – territory includes the capital Tehran, the Urmia and Salmas plains

- Diocese of Nohadra and Russia – established in 1999 with jurisdiction include the indigenous communities of Dohuk and Erbil, along with Russia and ex-Soviet states such as Armenia and Georgia.

- Diocese of Europe – its territory lies in western Europe and includes close to 10 sovereign states: Denmark, Sweden, Great Britain, Germany, The Netherlands, France, Belgium, Austria, Finland, Norway and Greece.

- Diocese of Eastern USA – formerly the Patriarchal Archdiocese from 1994 until 2012 . The territory includes the large Illinois community, along with smaller parishes in Michigan, New England and New York.

- Diocese of Western USA-North – jurisdiction includes parishes in Western USA and northern California. Some of the parishes are San Francisco, San Jose, Modesto, Turlock, Ceres, Seattle, and Sacramento.

- Diocese of Western USA-South – jurisdiction includes parishes in Arizona and southern California.

- Diocese of Canada – includes the territory of Toronto, Windsor, Hamilton and all Canada

Structure: archdioceses and dioceses

- Archdiocese of India – covers India.

- Archdiocese of Iraq, Iran, and Russia – covers the indigenous territory of the church in Iraq except Northern areas. The archdiocese's territory includes the cities and surroundings of Baghdad, Basra, Kirkuk, and Mosul.

- Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand, and Lebanon – covers Australia and New Zealand

- Diocese of Syria – covers Syria and Lebanon.

- Diocese of Europe – its territory lies in western Europe and includes close to 10 sovereign states: Denmark, Sweden, Great Britain, Germany, Netherlands, France, Belgium, Austria, Finland, Norway and Greece.

- Diocese of Eastern USA – formerly the Patriarchal Archdiocese from 1994 until 2012 . The territory includes the large Illinois community, along with smaller parishes in Michigan, New England and New York.

- Diocese of Western USA – jurisdiction includes parishes in Western USA other than California. The states are: Texas, Arizona and Nevada.

- Diocese of California – jurisdiction includes parishes in California, Oregon and Washington. Some of the parishes are San Francisco, San Jose, Modesto, Turlock, Ceres, and Sacramento

- Diocese of Canada – includes the territory of Toronto, Windsor, Hamilton and all Canada

Members of the Holy Synod

MarGewargis Sliwa: 121st Catholicos-Patriarch

- Aprem Mooken: Metropolitan of Malabar and India

- Meelis Zaia: Metropolitan of Australia, New Zealand and Lebanon

- Sargis Yosip: Bishop Emeritus of Baghdad (residing in Modesto, California)

- Isaac Yousif: Bishop of Dohuk-Erbil and Russia

- Aprem Nathniel: Bishop of Syria

- Narsai Benyamin: Bishop of Iran

- Aprim Khamis: Bishop of Western United States

- Emmanuel Yosip: Bishop of Canada

- Odisho Oraham: Bishop of Europe

- Awa Royel: Bishop of California and Secretary of the Holy Synod

- Paulus Benjamin: Bishop of Eastern United States

- Yohannan Joseph: Auxiliary Bishop of India

- Awgin Kuriakose: Auxiliary Bishop of India

See also

- Abda of Hira

- Chaldean Syrian Church in India (also known as Assyrian Church of the East in India)

- Church of the East

- Dioceses of the Church of the East to 1318

- Dioceses of the Church of the East, 1318–1552

- Dioceses of the Church of the East, 1552–1913

- List of Patriarchs of the Church of the East

- Assyrian settlements

- Assyrian Tribes

References

Bibliography

- Christoph Baumer, The Church of the East, an Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2006), ISBN 1-84511-115-X

- Baum, Wilhem, and Dietmar Winkler, The Church of the East: A Concise History (London and New York: Routledge Curzon, 2003)

- Aprem Mooken, The Assyrian Church of the East in the Twentieth Century. Mōrān ’Eth’ō, 18. (Kottayam: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute, 2003).

- Jenkins, Phillip "The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia — and How It Died (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2008)

- Weatherford, Jack (2004). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80964-4.

- Erica Hunter, "The Church of the East in Central Asia," Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 78, no.3 (1996), 129–142.

- W. Klein, Das Nestorianische Christentum an den Handelswegen durch Kyrgyzstan, Silk Road Studies 3 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2000).

- A. C. Moule, Christians in China before the year 1550, (London: SPCK, 1930).

- P. Y. Saeki, Nestorian Documents and Relics in China, 2nd ed., (Tokyo: Maruzen, 1951).

- Seleznyov, Nikolai N., "Nestorius of Constantinople: Condemnation, Suppression, Veneration, With special reference to the role of his name in East-Syriac Christianity" in: Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 62:3–4 (2010): 165–190.

Notes

- ↑ Holy Apostolic Assyrian Church of the East Official News Website

- ↑ "Nestorian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ↑ "The Church of the East – Mark Dickens". The American Foundation for Syriac Studies. 2012-10-05. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ↑ Binns, John (2002). An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66738-8., page 28

- ↑ Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3., p.351-352

- ↑ Habbi, 99–132 and 199–230; Wilmshurst, 21–2

- ↑ "Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East". Oikoumene.org. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

St Peter, the chief of the apostles added his blessing to the Church of the East at the time of his visit to the see at Babylon, in the earliest days of the church: '... The chosen church which is at Babylon, and Mark, my son, salute you ... greet one another with a holy kiss ...' ( I Peter 5:13–14).

- ↑ J. M. Fiey, Jalons pour une histoire de l'eglise en Iraq, (Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO, 1970)

- ↑ M.-L. Chaumont, La Christianisation de l'empire Iranien, (Louvain: Peeters, 1988).

- ↑ Henry Hill, Light from the East, (Toronto Canada: Anglican Book Centre, 1988) p. 105.

- 1 2 Cross, F.L. & Livingstone E.A. (eds), Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 351

- ↑ Leonard M Outerbridge, The Lost Churches of China, (Westminster Press, USA, 1952)

- ↑ http://www.cds.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/wp322.pdf

- ↑ "NSC NETWORK – Early references about the Apostolate of Saint Thomas in India, Records about the Indian tradition, Saint Thomas Christians & Statements by Indian Statesmen". Nasrani.net. Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ Charles A. Frazee, Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453–1923, Cambridge University Press, 2006 ISBN 0-521-02700-4

- ↑ Chaldean Catholic Church (Eastern Catholic), The new Catholic Encyclopedia, The Catholic University of America, Vol. 3, 2003 p. 366.

- ↑ George V. Yana (Bebla), "Myth vs. Reality" JAA Studies, Vol. XIV, No. 1, 2000 p. 80

- ↑ http://www.aina.org/books/com/com.htm

- ↑ Murre-van den Berg, Heleen H.L. (1999). "The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. Beth Mardutho. 2 (2): 235–264. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- 1 2 Cross, F. L. & Livingstone E.A. (eds), Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.351

- 1 2 Baum, Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 0-415-29770-2. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ↑ Baum, Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0-415-29770-2. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ↑ Baum, Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. pp. 148–149. ISBN 0-415-29770-2. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ↑ Baum, Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 0-415-29770-2. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- 1 2 Baum, Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. pp. 150–155. ISBN 0-415-29770-2. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Holy Synod Announcement – Passing of Catholicos-Patriarch". Holy Synod of the Assyrian Church of the East. Retrieved 2015-09-18.

- ↑ "Notice from the Locum Tenens". Holy Synod of the Assyrian Church of the East. Retrieved 2015-09-18.

- ↑ Henry Hill, Light from the East, (Toronto Canada: Anglican Book Centre, 1988) p107.

- 1 2 Cross, F.L. & Livingstone E.A. (eds), Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.78

- ↑ Cross, F.L. & Livingstone E.A. (eds), Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford University Press, 1997, p.1339

- ↑ Aprem Mooken, p.18

- ↑ "see for example". Churchoftheeastflint.org. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

External links

- Official website

- Assyrian Church of the East at DMOZ

- An Unofficial Website on the Church of the East – An informational site

- Article on the Assyrian Church of the East by Ronald Roberson on the CNEWA website

- Documentary film 'The last Assyrians', a history of Aramaic speaking Christians

- Qambel Maran- Syriac chants from South India- a review and liturgical music tradition of Syriac Christians revisited

- Traditions and rituals among the Syrian Christians of Kerala

- Guidelines for Chaldean Catholics receiving the Eucharist in Assyrian Churches

- Statement of the Holy Synod Of The Coptic Orthodox Church regarding the Dialogue between the Syrian and Assyrian Churches at the Wayback Machine (archived August 7, 2004)

- Khader Khano, the first native-born Assyrian to be ordained priest in Jerusalem in over 100 years

- Common Christological Declaration Between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East, 1994

.jpg)