Demerara rebellion of 1823

|

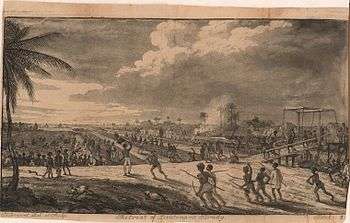

Slaves force the retreat of European soldiers led by Lt Brady. | |

| Date | 18–20 August 1823 |

|---|---|

| Location | Demerara |

| Participants | Jack Gladstone, Quamina, >10,000 slaves, plantocracy |

| Outcome | Revolt subdued, hundreds of slaves killed. |

The Demerara rebellion of 1823 was an uprising involving more than 10,000 slaves that took place in the Crown colony of Demerara-Essequibo (now part of Guyana). The rebellion, which took place on 18 August 1823 and lasted for two days, was led by slaves with the highest status. In part they were reacting to poor treatment and a desire for freedom; in addition, there was a widespread, mistaken belief that Parliament had passed a law for emancipation, but it was being withheld by the colonial rulers. Instigated chiefly by Jack Gladstone, a slave at "Success" plantation, the rebellion also involved his father, Quamina, and other senior members of their church group. Its English pastor, John Smith, was implicated.

The largely non-violent rebellion was brutally crushed by the colonists under governor John Murray. They killed many slaves: estimates of the toll from fighting range from 100 to 250. After the insurrection was put down, the government sentenced another 45 men to death, and 27 were executed. The executed slaves' bodies were displayed in public for months afterwards as a deterrent to others. Jack was deported to the island of Saint Lucia after the rebellion following a clemency plea by Sir John Gladstone, the owner of "Success" plantation. John Smith, who had been court-martialed and was awaiting news of his appeal against a death sentence, died a martyr for the abolitionist cause.

News of Smith's death strengthened the abolitionist movement in Britain. Quamina, who is thought to have been the actual leader of the rebellion, was declared a national hero after Guyana's independence. Streets and monuments have been dedicated to him in the capital of Georgetown, Guyana.

Context

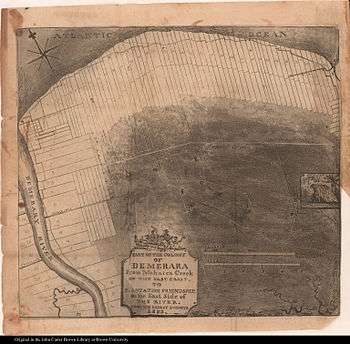

Demerara was first colonised by the Dutch in the 17th century under the auspices of the Dutch West India Company (DWIC). The economy, initially based on trade, began to be superseded in the 18th century by sugar cane cultivation on large plantations. The Demerara region was opened to settlement in 1746, and new opportunities attracted British settlers from nearby Barbados. By 1760, they had become the largest contingent in Demerara; the 1762 business registers showed that 34 of 93 plantations owned by Englishmen.[1] The British were a major external threat to Dutch control over the colonies from 1781 until 1796, when Britain obtained de facto control. Following a raid by privateers in February 1781, British occupation lasted until January 1782, when the island was recaptured by the French, then allied with the Dutch.[1]

The British transferred rule of Demerara to the Dutch in 1802 under the terms of the Peace of Amiens, but took back control of it a year later.[2] In 1812, the British merged Demerara and Essequibo into the colony of Demerara-Essequibo.[2] The colonies were ceded to Britain by treaty between the Netherlands and Britain on 13 August 1814.[2] Stabroek, as the colony's capital was known under the Dutch, was renamed as Georgetown in 1812. The colonial powers appointed a governor to rule in their stead, and the local legislation was decided on by a Court of Policy.[1]

The mainstay of its economy was sugar, grown on cane plantations worked by slaves.[3][1] The sale of the crop in Britain enjoyed preferential terms.[4] There were 2,571 declared slaves working on 68 plantations in Essequibo, and 1,648 slaves in Demerara in 1762. These numbers were known to be much understated, as the slave headcount was the basis of taxation. By 1769, there were 3,986 declared slaves for Essequibo's 92 plantations and 5,967 for Demerara's 206 plantations.[1] The slave labour was in short supply and expensive due to the trading monopoly of the DWIC, and smuggling from Barbados was rife.[1] Dutch colonists ensured white dominance over their growing slave population through the collaboration of indigenous natives, who strongly resisted white domination but could also be relied upon to take up arms against any Spanish incursions.[1] When slaves rose up in Berbice in 1763, natives blocked the border to prevent the disruption from spreading into Demerara.[1]

Rapid expansion of plantations in the 19th century increased demand for African slaves at a time when supplies were reduced.[1] The supply shortage of labour for production was exacerbated by the British abolition of trade in slaves in the Slave Trade Act 1807.[4] The population consisted of 2,500 whites, 2,500 freed blacks, and 77,000 slaves.[5] Ethnically, there were 34,462 African-born as against 39,956 "creole Negroes" by 1823 in Demerara and Essequibo.[4] Treatment of slaves were markedly different from owner to owner, and from plantation to plantation.[4] Plantations managed by agents and attorneys for absentee owners were common. Caucasian owners and managers were prevalent, and there were very few mixed-race "mulattoes" who advanced to become managers and owners. Lower-class whites and coloureds were considered "superior", giving them access to skilled work.[4] Blacks who performed skilled work, or worked within households and enjoyed greater autonomy, were regarded as having higher-status than other slaves. Slaves who toiled in the fields would work under drivers also slaves, but who had delegated authority of plantation overseers.[4]

The plantations

Although some plantation owners were enlightened or paternalistic, the slave population was on the whole poorly treated.[4] Churches for whites existed from the inauguration of the colonies, but slaves were barred from worshipping before 1807 as colonists feared education and Christianisation would lead slaves to question their status and lead to dissatisfaction. Indeed, a Wesleyan missionary who arrived in 1805 wanting to set up a church for slaves was immediately repatriated by order of the governor.[4] The London Missionary Society (LMS) entered Guyana shortly after the end of the slave trade at the behest of a plantation owner who believed that slaves ought to have access to religious teachings.[6][7] Hermanus Post, a naturalised Englishman of Dutch descent, advocated teaching of religion and literacy. The idea, considered radical at the time, was supported by some who may have thought religion was to be offered as a consolation in place of emancipation.[8] The colonial administration was hostile to the idea. It was written in the official journal, Royal Gazette, in 1808: "It is dangerous to make slaves Christians, without giving them their liberty."[9] Others strongly opposed.[4] Other plantation owners, who felt that teaching slaves anything other than their duties to their masters would lead to "anarchy, chaos and discontent" and precipitate the destruction of the colony. Post ignored these protestations and made facilities available for worship.[10][4] The facilities were easily outgrown by popularity of worship within just eight months.[10] The LMS contributed £100; Post gave the land and paid the balance, and a chapel with 600-person capacity was inaugurated on 11 September 1808. He also had a house constructed for the minister at a cost of £1200, of which £200 was subscribed by other "respectable inhabitants of the colony".[11][7]

The first pastor, Reverend John Wray, arrived in February 1808 and spent five years there; his wife operated a girls' school for white children.[4] After the chapel's construction, the owner wrote of improvements:

They were formerly a nuisance to the neighbourhood, on account of their drumming and dancing two or three nights in the week, and were looked on with a jealous eye on account of their dangerous communications; but they have now become the most zealous attendants on public worship, catechising, and private instructions. No drums are heard in this neighbourhood, except where the owners have prohibited the attendance of their slaves [at the church]. Drunkards and fighters have changed into sober and peaceable people, and endeavour to please those who are set over them.

Post sought to have more missionaries appointed to other places in the colony. However, Post died in 1809, and was lamented by his slaves. Conditions of his slaves markedly deteriorated under new management – they were once again subject to whipping and forced to work on Saturdays and Sundays.[10] Soon after Wray arrived in 1808, he fought for the rights of slaves in the colony to attend church services which would take place nightly. When Governor Henri Guillaume Bentinck declared all meetings after dark illegal, Wray obtained the support of some plantation owners and managers. Armed with their testimonials, he sought to confront Bentinck but was refused audience. Wray went to London to appeal directly to the government.[13]

When Wray was transferred to nearby Berbice at the end of his term, the mission was without a pastor for three years.[4] John Smith, his replacement sent to the colony by the LMS, was equally welcomed by the slaves.[8] Writing to the LMS, Smith said that the clergy was explicitly ordered to say nothing that would cause slaves' disenchantment with their masters or dissatisfaction with their status. Many in the colony resented the presence of the preachers, whom they believed were spies to the abolitionist movement in London. They feared that the religious teachings and the liberal attitudes promoted would eventually cause slaves to rebel.[14] Colonists interrupted services, threw stones at the churches, barred ministers' access to certain plantations, refusing permission to build chapels on plantation land;[4] slaves were stopped from attending services at every turn.[15] Smith received a hostile reception from the Governor John Murray and from most colonists. They saw his chapel services as a threat to plantation output, and feared greater unrest.[8] Smith reported to the LMS the Governor had told him that "planters will not allow their negroes to be taught to read, on pain of banishment from the colony."[16][8][4]

Furthermore, religious instruction for slaves was endorsed by British Parliament, thus the plantation owners were obliged to permit slaves to attend despite their opposition. Colonists who attended were perceived by Smith to be disruptive or a distraction.[15] Some overseers attended only to prevent their own slaves from attending.[15] One of owners' complaints was that slaves had too far to walk to attend services. When Smith had requested land to erect a chapel from John Reed, owner of "Dochfour", the idea was vetoed by Governor Murray, allegedly because of complaints he had received about Smith.[17] Colonists even perverted the intention of a circular from Britain which mandated giving slaves passes to attend services[18] – on 16 August 1823, the Governor issued a circular which required slaves to obtain owners' special dispensation to attend church meetings or services, causing a sharp decline in attendance at services.[3]

At about the same time, Smith wrote a letter back to George Burder, the Secretary of the LMS, lamenting the conditions of the slaves:

Ever since I have been in the colony, the slaves have been most grievously oppressed. A most immoderate quantity of work has, very generally, been exacted of them, not excepting women far advanced in pregnancy. When sick, they have been commonly neglected, ill treated, or half starved. Their punishments have been frequent and severe. Redress they have so seldom been able to obtain, that many of them have long discontinued to seek it, even when they have been notoriously wronged.— Rev. John Smith, letter dated 21 August 1823, quoted in Jakobsson (1972:323)[8]

Da Costa noted that the slaves who rebelled all had motives which were underpinned by their status as chattels: the families of many were caught in the turbulent changes in ownership of plantations and feared being sold and/or split up (as in the case of the slave Telemachus); Christians frequently complained of being harassed and chastised for their belief or their worshipping (Telemachus, Jacky Reed, Immanuel, Prince, Sandy); female slaves reported being abused or raped by owners or managers (Betsy, Susanna). Slaves were also often punished for frivolous reasons. Many managers/owners (McTurk, Spencer) would insist that slaves work on Sundays, and deny passes to attend church; Pollard, manager of "Non Pareil" and "Bachelor's Adventure", was notoriously violent.[19] Quamina complained of frequently being deprived of his legal day off and missing church; unable to take care of his sickly wife, he found her dead one night after coming home.[20][21] Jack Gladstone, a slave on "Success",[4][22] who did not work under a driver and enjoyed considerable freedom,[22] learned of the debate about slavery in Britain, and had heard rumours of emancipation papers arriving from London.[22]

Among the plantation owners, Sir John Gladstone, father of British Prime Minister William, who had built his fortune as a trader, had acquired plantations in Demerara in 1812 through mortgage defaults. This included half share in "Success", one of the largest and most productive plantations there; he acquired the remaining half four years later. Gladstone switched the crop from coffee to sugar, and expanded his workforce of slaves from 160 to more than 330.[23] Sir John would continue to acquire Demeraran plantations, often at fire sale prices after the rebellion and well into the decade, and his agents would be able to optimise his assets across the different properties.[23] By the time emancipation was enacted in Britain in 1834, he owned four plantations – "Vreedenhoop", "Success", "Wales" and "Vreedestein".[24]

John Smith, writing in his journal on 30 August 1817, said that the slaves of "Success" complained about the work load and very severe treatment. Sir John Gladstone, believing that the slaves on his estates were properly treated, wrote a letter to the Missionary Society on 24 December 1824 to clear his name. He wrote that his intentions have "ever been to treat my people with kindness in the attention to their wants of every description, and to grant them every reasonable and practicable indulgence." He stated that the work gangs were doubled from 160 after production shifted to sugar from coffee.[25] Gladstone later maintained that

Even on Sugar Estates, the grinding [of the canes] ceases at sunset; and the boilers, the only parties that remain longer, finish cleaning up before nine o'clock ... Their general food, in addition to salt fish and occasionally salted provisions, consisted of plantains which they preferred to other food. Plantains were cultivated in the ordinary daily work of each estate, or purchased when deficient, and they were supplied with more than they could consume. The slaves were provided with clothing that was suitable for the climate and their situation ... They have the Sabbath and their other holydays to dispose of, for the purpose of religion, if so inclined.

Gladstone, who had never set foot on his plantation, had been deluded by his attorney in Demerara, Frederick Cort, into believing that it was seldom necessary to punish the slaves.[27] He asserted they were generally happy and contented, and were able to make considerable money by selling the surplus produce of their provision grounds. Subsequent to the revolt, the secretary of the London Missionary Society warned Gladstone that Cort had been lying, but Gladstone continued to identify himself with Cort and his other agents.[28][27] Robertson, his second son, inspected the estates from 22 November 1828 to 3 March 1829, during which he observed that Cort was "an idler and a deceiver" who had mismanaged one estate after another. Only then was Cort dismissed.[27] In Britain, Lord Howick and others criticised the concept of absentee landlords. Sir Benjamin d'Urban, who took up his office of Lieutenant Governor of Essequibo and Demerara in 1824, wrote to Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for the Colonies, on 30 September 1824, criticising "..the injudicious managers under whom too many of the slaves are placed; half educated men of little discretion, or command over their own caprices; good planters perhaps – but quite unfit to have the charge of bodies of men, although they might take very proper care of cattle".[29]

The revolt

Slaves with the highest status such as coopers, and some other who were members of Smith's congregation, were implicated in leading the rebellion[4] against the harsh conditions and maltreatment, demanding what they believed to be their right. Quamina and his son Jack Gladstone, both slaves on "Success" plantation, led their peers to revolt.[30] Quamina, a member of Smith's church,[3] had been one of five chosen to become deacons by the congregation soon after Smith's arrival.[31] In the British House of Commons in May 1823, Thomas Fowell Buxton introduced a resolution condemning the state of slavery as "repugnant to the principles of the British constitution and of the Christian religion", and called for its gradual abolition "throughout the British colonies".[8] In fact, the subject of these rumours were Orders in Council (to colonial administrations) drawn up by George Canning under pressure from abolitionists to ameliorate the conditions of slaves following a Commons debate. Its principal provisions were to restrict slaves' daily working hours to nine and to prohibit flogging for female slaves.[4]

Whilst the Governor or Berbice immediately made a proclamation upon receiving his orders from London, and instructed local parson John Wray to explain the provisions to his congregation,[4] John Murray, his counterpart in Demerara, had received the Order from London on 7 July 1823, and these measures proved controversial as they were discussed in the Court of Policy on 21 July and again on 6 August.[4][8] They were passed as being inevitable, but the administration made no formal declaration as to its passing.[4] The lack of formal declaration led to rumours that masters had received instructions to set the slaves free but were refusing to do so.[4] In the weeks prior to the revolt, he sought confirmation of the veracity of the rumours from other slaves, particularly those who worked for those in a position to know: he thus obtained information from Susanna, housekeeper/mistress of John Hamilton of "Le Resouvenir"; from Daniel, the Governor's servant; Joe Simpson from "Le Reduit" and others. Specifically, Simpson had written a letter which said that their freedom was imminent but which warned them to be patient.[32] Jack wrote a letter (signing his father's name) to the members of the chapel informing them of the "new law".[33]

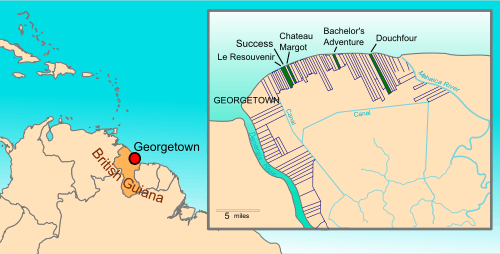

Those on "Le Resouvenir", where Smith's chapel was situated, also rebelled.[3] Quamina, who was well respected by slaves and freedmen alike,[34] initially tried to stop the slave revolt,[35] and urged instead for peaceful strike; he made the fellow slaves promise not to use violence.[33][36] As an artisan cooper who did not work under a driver, Jack enjoyed considerable freedom to roam about.[22] He was able to organise the rebellion through his formal and informal networks. Close conspirators who were church 'teachers' included Seaton (at "Success"), William (at "Chateau Margo"), David (at "Bonne Intention"), Jack (at "Dochfour"), Luke (at "Friendship"), Joseph (at "Bachelor's Adventure"), Sandy (at "Non Pareil"). Together, they finalised planning in the afternoon of Sunday 17 August for thousands of slaves to raise up against their masters the next morning.[37]

Joe of "Le Reduit" had informed his master at approximately 6 am that morning of a coordinated uprising planned the night before at Bethel chapel which would take place that same day. Captain Simpson, the owner, immediately rode to see the Governor, but stopped to alert several estates on the way into town. The governor assembled the cavalry, which Simpson was a part of.[38] Although the rebellion leaders had hoped for mass action by all slaves, the actual unrest involved about 13,000 slaves over some 37 estates located on the east coast, between Georgetown and Mahaica.[30] Slaves entered estates, ransacked the houses for weapons and ammunition, tied up the whites, or put some into stocks.[3][30] The very low number of white deaths is cited as proof that the uprising was largely free from violence from the slaves.[4] Accounts from witnesses indicate that the rebels exercised restraint, with only a very small number of white men were killed.[39][4] Some slaves took revenge on their masters or overseers by putting them in stocks, like they themselves had been before. Slaves went in large groups, from plantation to plantation, seizing weapons and ammunition and locking up the whites, promising to release them in three days. However, according to Bryant, not all slaves were compliant with the rebels; some were loyal to their masters and held off against the rebels.[39]

The Governor immediately declared martial law.[3] The 21st Fusiliers and the 1st West India Regiment, aided by a volunteer battalion, were dispatched to combat the rebels, who were armed mainly with cutlasses and bayonets on poles, and a small number of stands of rifles captured from plantations.[40] By the late afternoon on 20 August, the situation had been brought under control. Most of the slaves had been rounded up, although some of the rebels were shot whilst attempting to flee. On 22 August 1823, Lieutenant Governor Murray issued an account of the battles. He reported major confrontations on Tuesday morning at the Reed estate, "Dochfour", where ten to fifteen of the 800 rebels were killed; a skirmish at "Good Hope" felled "five or six" rebels. On Wednesday morning, six were killed at 'Beehive' plantation, forty rebels died at Elizabeth Hall. At a battle which took place at "Bachelor's Adventure", "a number considerably above 1500" were involved.[40]

The Lieutenant-Colonel having in vain attempted to convince these deluded people of their error, and every attempt to induce them to lay down their arms having failed, he made his dispositions, charged the two bodies simultaneously, and dispersed them with the loss of 100 to 150. On our side, we only had one rifleman slightly wounded.— Extract of communiqué from His Excellency the Commander-in-Chief, 22 August 1823[40]

After the slaves' defeat at "Bachelor's Adventure", Jack fled into the woods. A "handsome reward"[41] of one thousand guilder was offered for his capture.[42] The Governor also proclaimed a "FULL and FREE PARDON to all slaves who surrendered within 48 hours, provided that they shall not have been ringleaders (or guilty of Aggravated Excesses)".[43] Jack remained at large until he and his wife were captured by Capt. McTurk at "Chateau Margo", after a three-hour standoff on 6 September.[44]

Trials

On 25 August, the Governor Murray constituted a general court-martial, presided over by Lt.-Col. Stephen Arthur Goodman.[45] Despite the initial revolt passing largely peacefully with slave masters locked in their homes,[30] those who were considered ringleaders were tried at set up at different estates along the coast and executed by shooting; their heads were cut off and nailed to posts.[45] A variety of sentences were handed out, including solitary confinement, lashing, and death. Bryant (1824) records 72 slaves having been sentenced by court-martial at the time of publication. He noted that 19 of the 45 death sentences had been carried out; a further 18 slaves had been reprieved.[46] Quamina was among those executed; their bodies were hung up in chains by the side of a public road in front of their respective plantations and left to rot for months afterwards.[20][47] Jack Gladstone was sold and deported to St Lucia; Da Costa suggests that a letter Sir John had sent on his behalf resulted in clemency.[30]

John Smith was arraigned in court-martial before Lt. Col. Goodman on 13 October, charged with four offences: "promoting discontent and dissatisfaction in the minds of the Negro Slaves towards their Lawful Masters, Overseers and Managers, inciting rebellion; advising, consulting and corresponding with Quamina, and further aiding and abetting Quamina in the revolt; failure to make known the planned rebellion to the proper authorities; did not use his best endeavours to suppress, detain and restrain Quamina once the rebellion was under way."[48] The officers on the court martial judging Smith included a young Captain Colin Campbell, later to become Field Marshal Lord Clyde.[49]

Smith's trial concluded one month later, on 24 November. Smith was found guilty of the principal charges, and was given the death sentence. Pending an appeal, Smith was transferred from Colony House to prison, where he died of "consumption"[30] in the early hours of 6 February 1824;[50] To minimise the risk of stirring up slave sentiment, the colonists interred him at 4 am. The grave went without markings to avoid it becoming a rallying point for slaves.[51] The Royal reprieve arrived on 30 March.[50] Smith's death was a major step forward in the campaign to abolish slavery. News of his death was published in British newspapers, provoked enormous outrage and garnered 200 petitions to Parliament.[51]

Aftermath

The rebellion took place a few months after the founding of the Anti-Slavery Society, and had a strong impact on Britain.[3] Although public sentiment initially favoured the colonists, it changed with revelations.[4] The abolitionist debate which had flagged, was galvanised by the deaths of Smith and the 250 slaves.[52][53] The Martial law in Demerara was lifted on 19 January 1824.[54] In Demerara and Berbice, there was considerable anger towards the missionaries that resulted in their oppression. Demerara's Court of Policy passed an ordinance giving financial assistance to a church that was selected by plantation owners in each district. The Le Resouvenir chapel was seized and taken over by the Anglican Church.[4]

Under pressure from London, the Demerara Court of Policy eventually passed an 'Ordinance for the religious instruction of slaves and for meliorating their condition' in 1825 which institutionalised working hours and some civil rights for slaves. The weekend was to be from sunset on Saturday to sunrise on Monday; field work was also defined to be from 6 am to 6 pm, with a mandatory two-hour break.[4] A Protector of Slaves was appointed; whipping was abolished for women as was its use in the field. The rights to marriage and own property was legalised, as was the right to acquire manumission. Amendments and new ordinances continued to flow from London, each progressively establishing more civil rights for the slaves, but they were strongly resisted by the colonial legislature.[4]

Many planters refused to comply with their provisions. The confrontation continued as the planters challenged on several occasions the right of British government to pass laws binding on the colony, arguing that the Court of Policy has exclusive legislative power within the colony. Plantation owners who controlled the voting of the taxes disrupted administration by refusing to vote the civil list.[4]

In August 1833, the British parliament passed the 'Act for the abolition of slavery throughout the British Colonies, for promoting the industry of manumitted slaves, and for compensating the persons hitherto entitled to the services of such slaves', with effect from 1 August 1834. Plantation owners of British Guiana received £4,297,117 10s. 6½d. in compensation for the loss of 84,915 slaves.[4]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Demerara rebellion of 1823. |

- Abolition of slavery timeline

- Slavery in the British and French Caribbean

- Baptist War

- Haitian Revolution

- Vincent Ogé

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Smith, Raymond T. 1956, Chap. II.

- 1 2 3 Schomburgk 1840, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Révauger 2008, pp. 105–106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Smith, Raymond T. 1956, Chap. III.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, p. xviii.

- ↑ Rain 1892, p. 49.

- 1 2 McGowan, Winston (30 August 2007). "The 1823 Demerara slave rebellion (Part 2)" Stabroek News

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sheridan 2002, p. 247.

- ↑ Rain 1892, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 http://www.guyanatimesinternational.com/?p=27707

- ↑ Rain 1892, p. 35.

- ↑ Rain 1892, p. 39.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 119.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 3 Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 141.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 137.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 268.

- ↑ Rain 1892, p. 122.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, pp. 203–4.

- 1 2 McGowan, Winston (13 September 2007). "The 1823 Demerara slave rebellion (Part 3)" Stabroek News

- ↑ "Case Study 3: Demerara (1823) – Quamina and John Smith". The Abolition Project. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 182.

- 1 2 Sheridan 2002, p. 246.

- ↑ Sheridan 2002, p. 263.

- ↑ Sheridan 2002, p. 249.

- ↑ Sheridan 2002, p. 250.

- 1 2 3 Sheridan 2002, pp. 255–6.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 185.

- ↑ Sheridan 2002, pp. 260–1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sheridan 2002, p. 248.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 145.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 180, 196.

- 1 2 "PART II Blood, sweat, tears and the struggle for basic human rights". Guyana Caribbean Network. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 181.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, p. 75.

- ↑ Trust 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, pp. 191–2.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, p. 1.

- 1 2 Bryant 1824, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Bryant 1824, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, p. 83.

- ↑ Viotti da Costa 1994, p. 180.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, p. 55.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, pp. 83–4.

- 1 2 Bryant 1824, p. 60.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, p. 109.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, pp. 87–8.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, p. 91.

- ↑ Greenwood, ch.4

- 1 2 Bryant 1824, p. 94.

- 1 2 Hochschild 2006, p. 330.

- ↑ Hochschild 2006.

- ↑ Hinks, Peter P.; McKivigan, John R.; Williams, R. Owen (2006). Encyclopedia of antislavery and abolition. Greenwood Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-313-33143-X.

- ↑ Bryant 1824, p. 95.

Bibliography

- Bryant, Joshua (1824). Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August, 1823. Georgetown, Demerara: A. Stevenson at the Guiana Chronicle Office.

- Checkland, S. G. (1971). The Gladstones: a Family Biography, 1764–1851. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521082773.

- Hochschild, Adam (February 2006). Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-61907-0.

- Greenwood, Adrian (2015). Victoria's Scottish Lion: The Life of Colin Campbell, Lord Clyde. UK: History Press. p. 496. ISBN 0-75095-685-2.

- Rain, Thomas (1892). The life and labours of John Wray, pioneer missionary in British Guiana. London: J. Snow.

- Révauger, Cécile (October 2008). The Abolition of Slavery – The British Debate 1787–1840. Presse Universitaire de France. ISBN 978-2-13-057110-0.

- Sheridan, Richard B. (2002). "The Condition of slaves on the sugar plantations of Sir John Gladstone in the colony of Demerara 1812 to 1849" (pdf). New West Indian Guide. 76 (3/4): 243–269. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002536.

- Smith, Raymond T. (1956). "History: British Rule Up To 1928". The Negro Family in British Guiana. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Limited. ISBN 0415863295.

- Viotti da Costa, Emília (1994). Crowns of glory, tears of blood: the Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823. ISBN 0-19-510656-3.

- Schomburgk, Sir Robert H. (1840). A Description of British Guiana, Geographical and Statistical: Exhibiting Its Resources and Capabilities. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co. ISBN 978-0714619491.

- Trust, Graham (July 2010). John Moss of Otterspool (1782–1858) – Railway Pioneer Slave Owner Banker. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4520-0444-0.