Pequot War

| Pequot War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

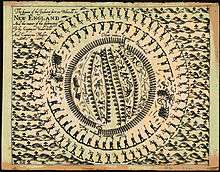

A 19th-century engraving depicting an incident in the Pequot War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Pequot tribe |

Native American Allies | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sachem Sassacus |

John Underhill John Mason Sachem Uncas Sagamore Wequash Sachem Miantonomoh | ||||||

The Pequot War was an armed conflict between the Pequot tribe and an alliance of the English colonists of the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Saybrook colonies and their Native American allies (the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes) which occurred between 1634 and 1638. The Pequots lost the war. At the end, about seven hundred Pequots had been killed or taken into captivity.[1] Hundreds of prisoners were sold into slavery to the West Indies.[2] Other survivors were dispersed. The result was the elimination of the Pequot as a viable polity in what is present-day Southern New England. The colonial authorities classified the tribe as extinct; however, survivors remained in the area and did regain recognition and land along the present-day Thames and Mystic rivers in southeastern Connecticut.[3]

Etymology

The name Pequot is a Mohegan term, the meaning of which is in dispute among Algonquian-language specialists. Most recent sources claim that "Pequot" comes from Paquatauoq (the destroyers), relying on the theories of early 20th-century authority on Algonquian languages Frank Speck, an anthropologist and specialist of Pequot-Mohegan in the 1920s-1930s. He had doubts about this etymology, believing that another term seemed more plausible, after translation relating to the "shallowness of a body of water".[4]

Origins

The Pequot and their traditional enemies the Mohegan were a single sociopolitical entity at one time. Anthropologists and historians contend that, sometime before contact with the Puritan English, they split into the two competing groups.[5] The earliest historians of the Pequot War speculated that the Pequot migrated from the upper Hudson River Valley toward central and eastern Connecticut sometime around 1500. These claims are disputed by the evidence of modern archaeology and anthropology finds.[6]

In the 1630s, the Connecticut River Valley was in turmoil. The Pequot aggressively worked to extend their area of control, at the expense of the Wampanoags to the north, the Narragansetts to the east, the Connecticut River Valley Algonquians and Mohegans to the west, and the Algonquian people of present-day Long Island to the south. The tribes contended for political dominance and control of the European fur trade. A series of smallpox epidemics over the course of the previous three decades had severely reduced the Native American populations due to their lack of immunity to the disease.[7] As a result, there was a power vacuum in the area.

The Dutch and the English from Western Europe were also striving to extend the reach of their trade into the interior to achieve dominance in the lush, fertile region. The colonies were new at the time, the original settlements having been founded in the 1620s. By 1636, the Dutch had fortified their trading post, and the English had built a trading fort at Saybrook. English Puritans from Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies settled at the four recently established river towns of Windsor (1632), Wethersfield (1633), Hartford (1635), and Springfield (1636.)

Belligerents

- Pequot: Sachem Sassacus

- Eastern Niantic

- Western Niantic: Sachem Sassious

- Mohigg: Sachem Uncas

- Niantic Sagamore Wequash

- Narragansett: Sachem Miantonomo

- Montauk or (Montaukett).

- Massachusetts Bay Colony: Governors Henry Vane and John Winthrop, Captains John Underhill and John Endecott

- Plymouth Colony: Governors Edward Winslow and William Bradford, and Captain Myles Standish

- Connecticut Colony: Thomas Hooker, Captain John Mason, Robert Seeley, Lt. William Pratt (c. 1609-1670)

- Saybrook Colony: Lion Gardiner

Causes for war

Before the war's inception, efforts to control fur trade access resulted in a series of escalating incidents and attacks that increased tensions on both sides. Political divisions between the Pequots and Mohegans widened as they aligned with different trade sources—the Mohegan with the English, and the Pequot with the Dutch (for a time; the peace did not last between the Dutch and Pequots). The Pequots assaulted a tribe of Indians who had tried to trade in the area of Hartford. Tensions grew as the Massachusetts Bay Colony became a stronghold for wampum, which the Narragansetts and Pequots had controlled up until 1633. John Stone (English rogue, smuggler, and privateer) and about seven of his crew were murdered by the Niantic, Western tributary clients of the Pequot. According to the Pequots' later explanations, they murdered him in reprisal for the Dutch murdering the principal Pequot sachem Tatobem, and they claimed to be unaware that Stone was English and not Dutch.[8] (Contemporaneous accounts claim that the Pequots knew Stone to be English.[9]) In the earlier incident, Tatobem had boarded a Dutch vessel to trade. Instead of conducting trade, the Dutch seized the sachem and appealed for a substantial amount of ransom for his safe return. The Pequot quickly sent bushels of wampum, but received only Tatobem's dead body in return.

Stone was from the West Indies and had been banished from Boston for malfeasance, including drunkenness, adultery, and piracy. He was known to have powerful connections in other colonies, as well as in London, and he was expected to use them against the Boston colony. Setting sail from Boston, Stone abducted two Western Niantic men, forcing them to show him the way up the Connecticut River. Soon after, he and his crew were suddenly attacked and killed by a larger group of Western Niantic.[10] The initial reactions in Boston varied from indifference to outright joy at Stone's death,[11] but the colonial officials later decided to protest the killing. They did not accept the Pequots' excuses that they had been unaware of Stone's nationality. Pequot sachem Sassacus sent some wampum to atone for the killing, but refused the colonists' demands that the warriors responsible for Stone's death be turned over to them for trial and punishment.[12]

On July 20, 1636, a respected trader named John Oldham was attacked on a trading voyage to Block Island. He and several of his crew were killed and his ship looted by Narragansett-allied Indians who sought to discourage English settlers from trading with their Pequot rivals. In the weeks that followed, colonial officials from Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, and Connecticut assumed that the Narragansett were the likely culprits. The Puritan officials knew that the Indians of Block Island were allies of the Eastern Niantic, who were allied with the Narragansett, and they became suspicious of the Narragansett.[13] The murderers meanwhile escaped and were given sanctuary with the Pequots.[14]

Battles

News of Oldham's death became the subject of sermons in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In August, Governor Vane sent John Endecott to exact revenge on the Indians of Block Island. Endecott's party of roughly 90 men sailed to Block Island and attacked two apparently abandoned Niantic villages. Most of the Niantic escaped, while two of Endecott's men were injured. The English claimed to have killed 14, but later Narragansett reports claimed that only one Indian was killed on the island. The Massachusetts Bay militia burned the villages to the ground. They carried away crops which the Niantic had stored for winter and destroyed what they could not carry. Endecott went on to Fort Saybrook.

The English at Saybrook were not happy about the raid, but agreed that some of them would accompany Endecott as guides. Endecott sailed along the coast to a Pequot village, where he repeated the previous year's demand for those responsible for the death of Stone, and now also for those who murdered Oldham. After some discussion, Endecott concluded that the Pequots were stalling and attacked, but most escaped into the woods. Endecott had his forces burn down the village and crops before sailing home.

Pequot raids

In the aftermath, the English of Connecticut Colony had to deal with the anger of the Pequots. The Pequots attempted to get their allies to join their cause, some 36 tributary villages, but were only partly effective. The Western Niantic (Nehantic) joined them, but the Eastern Niantic (Nehantic) remained neutral. The traditional enemies of the Pequot, the Mohegan and the Narragansett, openly sided with the English. The Narragansetts had warred with and lost territory to the Pequots in 1622. Now their friend Roger Williams urged the Narragansetts to side with the English against the Pequots.

Through the autumn and winter, Fort Saybrook was effectively besieged. People who ventured outside were killed. As spring arrived in 1637, the Pequots stepped up their raids on Connecticut towns. On April 23, Wongunk chief Sequin attacked Wethersfield with Pequot help. They killed six men and three women, a number of cattle and horses, and took two young girls captive. (They were daughters of William Swaine and were later ransomed by Dutch traders.)[15][16][17] In all, the towns lost about thirty settlers.

In May, leaders of Connecticut river towns met in Hartford, raised a militia, and placed Captain John Mason in command. Mason set out with ninety militia and seventy Mohegan warriors under Uncas; their orders were to directly attack the Pequot at their fort.[18] At Fort Saybrook, Captain Mason was joined by John Underhill with another twenty men. Underhill and Mason then sailed from Fort Saybrook to Narragansett Bay, a tactic intended to mislead Pequot spies along the shoreline into thinking that the English were not intending an attack. After gaining the support of 200 Narragansetts, Mason and Underhill marched their forces with Uncas and Wequash Cooke approximately twenty miles towards Mistick Fort (present-day Mystic). They briefly camped at Porter's Rocks near the head of the Mystic River before mounting a surprise attack just before dawn.

The Mystic massacre

The Mystic Massacre started in the predawn hours of May 26, 1637 when English forces led by Captains John Mason and John Underhill, along with their Indian allies from the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes, surrounded one of two main fortified Pequot villages at Mistick. Only 20 soldiers breached the palisade's gate and were quickly overwhelmed, to the point that they used fire to create chaos and facilitate their escape from within. The ensuing conflagration trapped the majority of the Pequots and caused their death; those who managed to exit were slain by the sword or musket from the others who surrounded the fort. Only a handful of approximately 500 men, women, and children survived what became known as the Battle of Mistick Fort. As the soldiers made the exhausted withdrawal march to their boats, they faced several attacks by frantic warriors from the other village of Weinshauks, but again the Pequots suffered very heavy losses versus relatively few by the Colonists.

Mason later declared that the attack against the Pequots was the act of a God who "laughed his Enemies and the Enemies of his People to scorn making [the Pequot fort] as a fiery Oven... Thus did the Lord judge among the Heathen, filling [Mystic] with dead Bodies."[19] Of the estimated 500 Pequots present at Mystic that day, only seven survived to be taken prisoner, while another seven escaped to the woods.[20]

The Narragansetts and Mohegans with Mason and Underhill's colonial militia were horrified by the actions and "manner of the Englishmen's fight... because it is too furious, and slays too many men."[21][22] The Narragansetts attempted to leave and return home but were cut off by the Pequots from the other village of Weinshauks and had to be rescued by Underhill's men—after which they reluctantly rejoined the colonists for protection and were utilized to carry the wounded, thereby freeing up more soldiers to fend off the numerous attacks along the withdrawal route.

War's end

The destruction of people and the village at Mistick Fort and losing even more warriors during the withdrawal pursuit broke the Pequot spirit, and they decided to abandon their villages and flee westward to seek refuge with the Mohawk tribe. Sassacus led roughly 400 warriors along the coast; when they crossed the Connecticut River, the Pequots killed three men whom they encountered near Fort Saybrook.

In mid-June, John Mason set out from Saybrook with 160 men and 40 Mohegan scouts led by Uncas. They caught up with the refugees at Sasqua, a Mattabesic village near present-day Fairfield, Connecticut. The colonists memorialized this event as the Fairfield Swamp Fight (not to be confused with the Great Swamp Fight during King Philip's War). The English surrounded the swamp and allowed several hundred to surrender, mostly women and children, but Sassacus slipped out before dawn with perhaps eighty warriors and continued west.

Sassacus and his followers had hoped to gain refuge among the Mohawk in present-day New York. However, the Mohawk instead murdered him and his bodyguard, afterwards sending his head and hands to Hartford (for reasons which were never made clear).[23] This essentially ended the Pequot War; colonial officials continued to call for hunting down what remained of the Pequots after war's end, but they granted asylum to any who went to live with the Narragansetts or Mohegans.[24]

Aftermath

In September, the Mohegans and Narragansetts met at the General Court of Connecticut and agreed on the disposition of the Pequot survivors. The agreement is known as the first Treaty of Hartford and was signed on September 21, 1638. About 200 Pequots survived the war; they finally gave up and submitted themselves under the authority of the sachem of the Mohegans or Naragansetts:[25]:18[26]

| “ | There were then given to Onkos, Sachem of Monheag, Eighty; to Myan Tonimo, Sachem of Narragansett, Eighty; and to Nynigrett, Twenty, when he should satisfy for a Mare of Edward Pomroye’s killed by his Men. The Pequots were then bound by Covenant, That none should inhabit their native Country, nor should any of them be called PEQUOTS any more, but Moheags and Narragansatts for ever.[25]:18 | ” |

Other Pequots were enslaved and shipped to Bermuda or the West Indies, or were forced to become household slaves in English households in Connecticut and Massachusetts Bay.[27] The Colonies essentially declared the Pequots extinct by prohibiting them from using the name any longer.

The colonists attributed their victory over the hostile Pequot tribe to an act of God:

| “ | Let the whole Earth be filled with his glory! Thus the lord was pleased to smite our Enemies in the hinder Parts, and to give us their Land for an Inheritance.[25]:20 | ” |

This was the first instance wherein Algonquian peoples of southern New England encountered European-style warfare. After the Pequot War, there were no significant battles between Indians and southern New England colonists for about 38 years. This long period of peace came to an end in 1675 with King Philip's War.

Historical accounts and controversies

The earliest accounts of the Pequot War were written by the victors within one year of the war. Later histories, with few exceptions, recounted events from a similar perspective, restating arguments first used by the war's military leaders, such as John Underhill and John Mason, as well as Puritans Increase Mather and his son Cotton Mather.[28]

Recent historians and others have reviewed these accounts. In 2004, an artist and archaeologist teamed up to evaluate the sequence of events in the Pequot War. Their popular history took issue with events and whether John Mason and John Underhill wrote the accounts that appeared under their names.[29] The authors have been adopted as honorary members of the Lenape Pequots.

Most modern historians do not debate questions of the outcome of the battle or its chronology, such as Alfred A. Cave, a specialist in the ethnohistory of colonial America. However, Cave contends that Mason and Underhill's eyewitness accounts, as well as the contemporaneous histories of Mather and Hubbard, were more "polemical than substantive."[30] The causes of the outbreak of hostilities, the reasons for the English fear of the Pequots, and the ways in which the English dealt with and wrote about the Pequots have been re-evaluated within a larger context than daily colonial life.

Some modern historians have placed the background of the Pequot War within the context of European history (in which religious wars gave rise to increased violence) and Dutch and English colonization in North America, as well as the ambitions and wars of contending Indian tribes during the first half of the 17th century. Such historians have doubts about traditional histories, characterizing them as hegemonic narratives that valorize Puritans at the expense of a "demonized" Indian population. Alden T. Vaughan, a noted historian of colonial America, at first was a critic of the Pequots. Later he wrote that the Pequots were not "solely or even primarily responsible" for the war. He went on, "The Bay colony's gross escalation of violence ... made all-out war unavoidable; until then, negotiation was at least conceivable."[31]

Documentaries

- In 2004, PBS aired the television documentary Mystic Voices: The Story of the Pequot War.

- The Mystic Massacre was featured in the 2006 History Channel series 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America.

See also

Notes

- ↑ John Winthrop, Journal of John Winthrop. ed. Dunn, Savage, Yeandle (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), 228.

- ↑ Lion Gardiner, "Relation of the Pequot Warres", in History of the Pequot War: The Contemporary Accounts of Mason, Underhill, Vincent, and Gardiner (Cleveland, 1897), p. 138; Ethel Boissevain, "Whatever Became of the New England Indians Shipped to Bermuda to be Sold as Slaves," Man in the Northwest 11 (Spring 1981), pp. 103-114; Karen O. Kupperman, Providence Island, 1630-1641: The Other Puritan Colony (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), p. 172

- ↑ Laurence M. Hauptman and James D. Wherry, eds.The Pequots in Southern New England: The Fall and Rise of an Indian Nation (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990).

- ↑ Frank Speck, "Native Tribes and Dialects of Connecticut: A Monhigg-Pequot Diary," Annual Reports of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology 43 (1928): 218.

- ↑ See Carrol Alton Means, "Mohegan-Pequot Relationships, as Indicated by the Events Leading to the Pequot Massacre of 1637 and Subsequent Claims in the Mohegan Land Controversy," Archaeological Society of Connecticut Bulletin 21 (2947): 26-33.

- ↑ For archaeological investigations disproving Hubbard's theory of origins, see Irving Rouse, "Ceramic Traditions and Sequences in Connecticut," Archaeological Society of Connecticut Bulletin 21 (1947): 25; Kevin McBride, "Prehistory of the Lower Connecticut Valley" (Ph.D. diss., University of Connecticut, 1984), pp. 126-28, 199-269; and the overall evidence on the question of Pequot origins in Means, "Mohegan-Pequot Relationships," 26-33. For historical research, refer to Alfred A. Cave, "The Pequot Invasion of Southern New England: A Reassessment of the Evidence," New England Quarterly 62 (1989): 27-44; and for linguistic research, see Truman D. Michelson, "Notes on Algonquian Language," International Journal of American Linguistics 1 (1917): 56-57.

- ↑ See Alfred W. Crosby, "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., vol. 33, no. 2 (Apr. 1976) , pp. 289-299; Arthur E. Spiero and Bruce E. Speiss, "New England Pandemic of 1616-1622: Cause and Archaeological Implication," Man in the Northeast 35 (1987): 71-83; and Dean R. Snow and Kim M. Lamphear, "European Contact and Indian Depopulation in the Northeast: The Timing of the First Epidemics," Ethnohistory 35 (1988): 16-38.

- ↑ Alfred Cave, The Pequot War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996), pp. 58-60.

- ↑ http://mith.umd.edu/eada/html/display.php?docs=bradford_history.xml p. 565

- ↑ Cave, The Pequot War, pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Cave, The Pequot War, pp. 72, 74.

- ↑ Cave, The Pequot War, pp. 76.

- ↑ Cave, The Pequot War, pp. 104-105.

- ↑ https://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/nereligioushistory/bradford-plimoth/bradford-plymouthplantation.pdf p. 491

- ↑ Atwater, Elias (1902). History of the Colony of New Haven to Its Absorption Into Connecticut. The Journal Publishing Company. p. 610.

- ↑ Griswold, Wick (2012). A History of the Connecticut River. The History Press. p. 45.

- ↑ Games, Alison (1999). Migration and the Origins of the English Atlantic World. Harvard College. p. 167.

- ↑ "The History of the Pequot War". pequotwar.org. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ John Mason's justification for burning Mystic in A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially of the Memorable taking of their Fort at Mistick in Connecticut in 1637 (Boston: S. Kneeland & T. Green, 1736), p. 30.

- ↑ Mason, John. A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially of the Memorable taking of their Fort at Mistick in Connecticut in 1637 (Boston: S. Kneeland & T. Green, 1736), p. 10.

- ↑ William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation, 1620–1647, ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966), p. 29.

- ↑ John Underhill, Newes from America; or, A New and Experimentall Discoverie of New England: Containing, a True Relation of their War-like Proceedings these two yeares last past, with a figure of the Indian fort, or Palizado (London: I. D[awson] for Peter Cole, 1638), p. 84.

- ↑ http://mith.umd.edu/eada/html/display.php?docs=bradford_history.xml p. 582

- ↑ http://mith.umd.edu/eada/html/display.php?docs=bradford_history.xml p. 582

- 1 2 3 Mason, John (1736). Paul Royster, ed. "A Brief History of the Pequot War". University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ↑ William Bradford and other contemporaries indicate that the Pequots who chose to were permitted to join with the Narragansett or Mohegan tribes—in the capacity of freemen, not as slaves. For first-hand accounts, see Lion Gardiner, "Relation of the Pequot Warres" in History of the Pequot War: The Contemporary Accounts of Mason, Underhill, Vincent, and Gardiner (Cleveland, 1897), p. 138, and John Mason's account in the same volume.

- ↑ For historical analyses of Pequot enslavement, see Michael L. Fickes, "'They Could Not Endure That Yoke': The Captivity of Pequot Women and Children after the War of 1637," New England Quarterly, vol. 73, no. 1. (Mar., 2000), pp. 58-81; Ethel Boissevain, "Whatever Became of the New England Indians Shipped to Bermuda to be Sold as Slaves," Man in the Northwest 11 (Spring 1981), pp. 103-114; and Karen O. Kupperman, Providence Island, 1630-1641: The Other Puritan Colony (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), p. 172.

- ↑ For a 19th-century account that reflects Mason, Underhill, and the Mathers, see William Hubbard, The History of the Indian Wars in New England 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel G. Drake, 1845), II:6-7. For narratives from the late 18th century, see Thomas Hutchinson, The History of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay (1793); the magisterial Francis Parkman, France and England in North America, ed. David Levin (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1983): I:1084, in addition to Richard Hildreth, The History of the United States of America 6 vols (New York, 1856), I:237-42 for the 19th century; and Howard Bradstreet, The History of the War with the Pequots Retold (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1933) for the first half of the twentieth century.

- ↑ Jack Dempsey and David R. Wagner (2004). Mystic Fiasco: How the Indians Won The Pequot War.

- ↑ Cave, The Pequot War, p. 2

- ↑ Alden T. Vaughan, "Pequots and Puritans: The Causes of the War of 1637," in Roots of American Racism: Essays on the Colonial Experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), p.194.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Bradford, William. Of Plimoth Plantation, 1620-1647, ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966).

- Gardiner, Lion. Leift Lion Gardener his Relation of the Pequot Warres (Boston: [First Printing] Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, 1833). Online edition (1901)

- Hubbard, William. The History of the Indian Wars in New England 2 vols. (Boston: Samuel G. Drake, 1845).

- Johnson, Edward. Wonder-Working Providence of Sion's Saviour in New England by Captain Edward Johnson of Woburn, Massachusetts Bay. With an historical introduction and an index by William Frederick Poole (Andover, MA: W. F. Draper, [London: 1654] 1867).

- Mason, John. A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially of the Memorable taking of their Fort at Mistick in Connecticut in 1637/Written by Major John Mason, a principal actor therein, as then chief captain and commander of Connecticut forces; With an introduction and some explanatory notes by the Reverend Mr. Thomas Prince (Boston: Printed & sold by. S. Kneeland & T. Green in Queen Street, 1736).Online edition

- Mather, Increase. A Relation of the Troubles which have Hapned in New-England, by Reason of the Indians There, from the Year 1614 to the Year 1675 (New York: Arno Press, [1676] 1972).

- Orr, Charles ed., History of the Pequot War: The Contemporary Accounts of Mason, Underhill, Vincent, and Gardiner (Cleveland, 1897).

- Underhill, John. Nevves from America; or, A New and Experimentall Discoverie of New England: Containing, a True Relation of their War-like Proceedings these two yeares last past, with a figure of the Indian fort, or Palizado. Also a discovery of these places, that as yet have very few or no inhabitants which would yeeld speciall accommodation to such as will plant there . . . By Captaine Iohn Underhill, a commander in the warres there (London: Printed by I. D[awson] for Peter Cole, and are to be sold at the signe of the Glove in Corne-hill neere the Royall Exchange, 1638). Online edition

- Vincent, Philip. A True Relation of the late Battell fought in New England, between the English, and the Salvages: VVith the present state of things there (London: Printed by M[armaduke] P[arsons] for Nathanael Butter, and Iohn Bellamie, 1637). Online edition

Secondary sources

- Adams, James T. The Founding of New England (Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1921).

- Apess, William. A Son of the Forest (The Experience of William Apes, a Native of the Forest Comprising a Notice of the Pequod tribe of Indians), and other writings, ed. Barry O'Connell (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, [1829] 1997).

- Bancroft, George. A History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent, 9 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1837–1866): I:402-404.

- Boissevain, Ethel. "Whatever Became of the New England Indians Shipped to Bermuda to be Sold as Slaves," Man in the Northwest 11 (Spring 1981), pp. 103–114.

- Bradstreet, Howard. The Story of the War with the Pequots, Retold (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1933).

- Cave, Alfred A. "The Pequot Invasion of Southern New England: A Reassessment of the Evidence," New England Quarterly 62 (1989): 27-44.

- _______. "Who Killed John Stone? A Note on the Origins of the Pequot War," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., vol. 49, no. 3. (Jul., 1992), pp. 509–521.

- ______. The Pequot War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996).

- Channing, Edward. A History of the United States (New York: Macmillan, 1912–1932).

- Cronon, William. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1985).

- Crosby, Alfred W. "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., vol. 33, no. 2 (Apr., 1976), pp. 289–299.

- De Forest, John W. History of the Indians of Connecticut from the Earliest known Period to 1850 (Hartford, 1853).

- Dempsey, Jack, and David R. Wagner, MYSTIC FIASCO: How the Indians Won The Pequot War. 249pp., 50 illustrations/photos, Annotated Chronology, Index. Scituate, MA: Digital Scanning Inc. 2004. See also "Mystic Massacre"

- Drinnon, Richard, Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire-Building (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997).

- Fickes, Michael L. "'They Could Not Endure That Yoke': The Captivity of Pequot Women and Children after the War of 1637," New England Quarterly, vol. 73, no. 1. (Mar., 2000), pp. 58–81.

- Freeman, Michael. "Puritans and Pequots: The Question of Genocide," New England Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 2. (Jun., 1995), pp. 278–293.

- Greene, Evarts P. The Foundations of American Nationality (New York: American Book Co., 1922).

- Hall, David. Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment: Popular Religious Belief in Early New England (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

- Hauptman, Laurence M. "The Pequot War and Its Legacies," in The Pequots in Southern New England: The Fall and Rise of an Indian Nation, ed. Laurence M. Hauptman and James D. Wherry (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), p. 69.

- Hildreth, Richard. The History of the United States of America (New York: Harper & Bros., 1856–60), I: 237-42.

- Hirsch, Adam J. "The Collision of Military Cultures in Seventeenth-Century New England," Journal of American History, vol. 74, no. 4. (Mar., 1988), pp. 1187–1212.

- Holmes, Abiel. The Annals of America: From the Discovery by Columbus in the Year 1492, to the Year 1826 (Cambridge: Hilliard and Brown, 1829).

- Howe, Daniel W. The Puritan Republic of the Massachusetts Bay in New England (Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill, 1899).

- Hutchinson, Thomas. The History of the Colony of Massachuset's Bay, From the first settlement thereof in 1628 (London: Printed for M. Richardson ..., 1765).

- Jennings, Francis P. The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (Chapel Hill: Institute of Early American History and Culture, University of North Carolina Press, 1975).

- Karr, Ronald Dale. "'Why Should You Be So Furious?': The Violence of the Pequot War," Journal of American History, vol. 85, no. 3. (Dec., 1998), pp. 876–909.

- Katz, Steven T. "The Pequot War Reconsidered," New England Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 2. (Jun., 1991), pp. 206–224.

- ______. "Pequots and the Question of Genocide: A Reply to Michael Freeman," New England Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 4. (Dec., 1995), pp. 641–649.

- Kupperman, Karen O. Settling with the Indians: The Meeting of English and Indian Cultures in America, 1580-1640 (Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1980).

- Lipman, Andrew. "'A meanes to knitt them togeather': The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War." William and Mary Quarterly Third Series, Vol. 65, No. 1 (2008): 3-28.

- Means, Carrol Alton. "Mohegan-Pequot Relationships, as Indicated by the Events Leading to the Pequot Massacre of 1637 and Subsequent Claims in the Mohegan Land Controversy," Archaeological Society of Connecticut Bulletin 21 (2947): 26-33.

- Macleod, William C. The American Indian Frontier (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1928).

- McBride, Kevin. "Prehistory of the Lower Connecticut Valley" (Ph.D. diss., University of Connecticut, 1984).

- Michelson, Truman D. "Notes on Algonquian Language," International Journal of American Linguistics 1 (1917): 56-57.

- Oberg, Michael. Uncas: First of the Mohegans (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003).

- Parkman, Francis. France and England in North America, ed. David Levin (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1983): I:1084.

- Salisbury, Neal. Manitou and Providence: Indians, Europeans, and the Making of New England, 1500-1643 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982).

- Segal, Charles M. and David C. Stineback, eds. Puritans, Indians, and Manifest Destiny (New York: Putnam, 1977).

- Snow, Dean R., and Kim M. Lamphear, "European Contact and Indian Depopulation in the Northeast: The Timing of the First Epidemics," Ethnohistory 35 (1988): 16-38.

- Speck, Frank. "Native Tribes and Dialects of Connecticut: A Mohegan-Pequot Diary," Annual Reports of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology 43 (1928).

- Spiero, Arthur E., and Bruce E. Speiss, "New England Pandemic of 1616-1622: Cause and Archaeological Implication," Man in the Northeast 35 (1987): 71-83

- Sylvester, Herbert M. Indian Wars of New England, 3 vols. (Boston: W.B. Clarke Co., 1910), 1:183-339.

- Trumbull, Benjamin. A Complete History of Connecticut: Civil and Ecclesiastical, From the Emigration of its First Planters, from England, in the Year 1630, to the Year 1764; and to the close of the Indian Wars (New Haven: Maltby, Goldsmith and Co. and Samuel Wadsworth, 1818).

- Vaughan, Alden T. "Pequots and Puritans: The Causes of the War of 1637," William and Mary Quarterly 3rd Ser., Vol. 21, No. 2 (Apr., 1964), pp. 256–269; also republished in Roots of American Racism: Essays on the Colonial Experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- ______. New England Frontier: Puritans and Indians 1620-1675 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995, Reprint).

- Willison, George F. Saints and Strangers, Being the Lives of the Pilgrim Fathers & their Families, with their Friends & Foes; & An Account of their Posthumous Wanderings in limbo, their Final Resurrection & Rise to Glory, & the Strange Pilgrimages of Plymouth Rock (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1945)

- Wilson, Woodrow. A History of the American People, 5 vols. (New York and London : Harper & Brothers, 1906).

External links

- 1736 version of John Mason's account

- "Pequot War timeline from Columbia University". Archived from the original on 2012-02-28.

- A summary of the Pequots and their history

- A brief history of the Pequot War

- Society of Colonial War's account

- Cape Cod Online: Worlds Rejoined.

- The Royal Gazette: Bermudians (Mohegans) and Pequots Reconnect

- P. Vincent, A True Relation of the Late Battell fought in New England online edition

- John Underhill, Newes from America online edition

- Lion Gardener, Relation of the Pequot Warres online edition