Battle of Blaauwberg

| Battle of Blaauwberg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

The Storming of the Cape of Good Hope | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Lieutenant General Sir David Baird | Lieutenant General Jan Willem Janssens | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,399 | 2,049 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 212 casualties | 353 casualties | ||||||

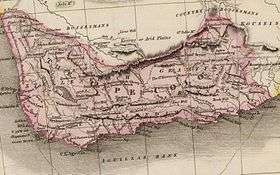

The Battle of Blaauwberg, also known as the Battle of Cape Town, fought near Cape Town on 8 January 1806, was a small but significant military engagement. It established British rule in South Africa, which was to have many ramifications for the region during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A bi-centennial commemoration was held in January 2006.

Background

The battle was an incident in Europe's Napoleonic Wars. At that time, the Cape Colony belonged to the Batavian Republic, a French vassal. Because the sea route around the Cape was important to the British, they decided to seize the colony in order to prevent it—and the sea route—from also coming under French control. A British fleet was despatched to the Cape in July 1805, to forestall French troopships which Napoleon had sent to reinforce the Cape garrison.

The colony was governed by Lieutenant General Jan Willem Janssens, who was also commander-in-chief of its military forces. The forces were small and of poor quality, and included foreign units hired by the Batavian government. They were backed up by local militia units.

Events

The first British warship reached the Cape on Christmas Eve 1805, and attacked two supply ships off the Cape Peninsula. Janssens placed his garrison on alert. When the main fleet sailed into Table Bay on 4 January 1806, he mobilised the garrison, declared martial law, and called up the militia.

After a delay caused by rough seas, two British infantry brigades, under the command of Lt Gen Sir David Baird, landed at Melkbosstrand, north of Cape Town, on 6 and 7 January. Janssens moved his forces to intercept them. He had decided that "victory could be considered impossible, but the honour of the fatherland demanded a fight". His intention was to attack the British on the beach and then to withdraw to the interior, where he hoped to hold out until the French troopships arrived.

However, on the morning of 8 January, while Janssens's columns were still slowly moving through the veld, Baird's brigades began their march to Cape Town, and reached the slopes of the Blaauwberg mountain (now spelled "Blouberg"), a few kilometres ahead of Janssens. Janssens halted and formed a line across the veld.

The battle began at sunrise, with exchanges of artillery fire. These were followed by an advance by Janssens's militia cavalry, and volleys of musket fire from both sides. One of Janssens's hired foreign units, in the centre of his line, turned and ran from the field. A British bayonet charge disposed of the units on Janssens's right flank, and he ordered his remaining troops to withdraw.

Janssens began the battle with 2,049 troops, and lost 353 in casualties and desertions. Baird began the battle with 5,399 men, and had 212 casualties.

From Blaauwberg, Janssens moved inland to a farm in the Tygerberg area, and from there his troops moved to the Elands Kloof in the Hottentots Holland Mountains, about 50km from Cape Town.

The British forces reached the outskirts of Cape Town on 9 January. To spare the town and its civilian population from attack, the commandant of Cape Town, Lieutenant-Colonel Hieronymus Casimir von Prophalow, sent out a white flag. He handed over the outer fortifications to Baird, and terms of surrender were negotiated later in the day. The formal Articles of Capitulation for the town and the Cape Peninsula were signed the following afternoon, 10 January, at a cottage at Papendorp (now the suburb of Woodstock) which became known as "Treaty Cottage." Although the cottage has long since been demolished, Treaty Street still commemorates the event. The tree under which they signed remains to this day.

_-_General_Janssens_at_the_Battle_of_Blaauwberg.jpg)

However, the Batavian Governor of the Cape, General Janssens, had not yet surrendered himself and his remaining troops and was following his plan to hold out for as long as he could, in the hope that the French troopships for which he had been waiting for months would arrive and save him. He had only 1,238 men with him, and 211 deserted in the days that followed.

Janssens held out in the mountains for a further week. Baird sent Brigadier General William Beresford to negotiate with him, and the two generals conferred at a farm belonging to Gerhard Croeser near the Hottentots-Holland Mountains on 16 January without reaching agreement. After further consideration, and consultation with his senior officers and advisers, Janssens decided that "the bitter cup must be drunk to the bottom". He agreed to capitulate, and the final Articles of Capitulation were signed on 18 January.

Uncertainty reigns as to where the Articles of Capitulation were signed. For many years it has been claimed that it was the Goedeverwachting estate (where a copy of the treaty is on display), but more recent research, published in Dr Krynauw's book Beslissing by Blaauwberg suggests that Croeser's farm (now the Somerset West golf course) may have been the venue. An article published in the 1820s by the then resident clergyman of the Stellenbosch district, Dr Borcherds, also points towards Croeser's farm.

The terms of the capitulation were reasonably favourable to the Batavian soldiers and citizens of the Cape. Janssens and the Batavian officials and troops were sent back to the Netherlands in March.

The British forces occupied the Cape until 13 August 1814, when the Netherlands ceded the colony to Britain as a permanent possession. It remained a British colony until it was incorporated into the Union of South Africa on 31 May 1910.

Articles of Capitulation

Summary of the Articles of Capitulation signed by Lt Col Von Prophalow, Maj Gen Baird and Cdre Popham on 10 January 1806:[1]

- Cape Town, the Castle, and circumjacent fortifications were surrendered to Great Britain;

- the garrison became prisoners of war, but officers who were colonists or married to colonists could remain at liberty as long as they behaved themselves;

- officers who were to be repatriated to Europe would be paid up to the date of embarkation and would be transported at British expense;

- all French subjects in the colony must return to Europe;

- inhabitants of Cape Town who had borne arms [i.e. burgher militiamen] could return to their occupations;

- all private property would remain free and untouched;

- all public property was to be inventoried and handed over;

- the burghers and inhabitants would retain all their rights and privileges, including freedom of worship;

- paper money in circulation would remain current;

- the Batavian government property that was to be handed over would serve as security for the paper money;

- prisoners of war would not be pressed into British service or be forced to enlist against their will;

- troops would not be quartered on the citizens of Cape Town;

- the two ships which had been sunk in Table Bay were to be raised by those who had sunk them, repaired, and handed over.

Summary of the Articles of Capitulation signed by Lt Gen Janssens and Brig Gen Beresford on 18 January 1806 and ratified by Maj Gen Baird on 19 January:[2]

- the colony and its dependencies were surrendered to Great Britain;

- the Batavian troops were to move to Simon's Town, with their guns, arms, baggage, and all the honours of war - the officers could retain their swords and horses, but all arms, treasure, public property, and horses were to be handed over;

- the Batavian troops would not be considered to be prisoners;

- Janssens' Hottentot (sic) troops were also to march to Simon's Town, after which they could either return home or join the British forces;

- the British commander-in-chief [Baird] would decide the position of those Batavian troops who were already prisoners of war;

- the British government would bear the expense of the Batavian troops' subsistence until they embarked;

- the Batavian troops would be transported to a port in the Batavian Republic;

- sick men who could not be transported would stay behind, at British expense, and be sent to Holland after they had recovered;

- the rights and privileges allowed to the citizens of Cape Town would also apply to the rest of the colony, except that the British could quarter troops on residents of the country districts;

- once embarked, the Batavian troops would be treated the same as British troops were when on board transport ships;

- Janssens would be allowed to send a despatch to Holland, and the British commanders would assist in forwarding it;

- decisions regarding the continuation of agricultural plans by one Baron van Hogendorp would be left to the future British government;

- any matter arising out of the Articles of Capitulation would be decided justly and honourably without preference to either party.

See also

References

Books

Anderson, Mark Robert Dunbar (2008). BLUE BERG. Britain Takes The Cape. Cape Town: Mark Anderson. ISBN 9780620413367.

Sources

- Lt Gen Janssens's Report (Cape Archives: ref VC80)

- Krynauw, D. Beslissing by Blaauwberg.

- Theal, GM. Records of the Cape Colony.

Coordinates: 33°45′22″S 18°27′56″E / 33.75611°S 18.46556°E