Dionysos, Greece

| Dionysos Διόνυσος | |

|---|---|

|

Dionysos Skyline | |

Dionysos | |

|

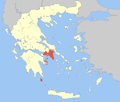

Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 38°6′N 23°52′E / 38.100°N 23.867°ECoordinates: 38°6′N 23°52′E / 38.100°N 23.867°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Attica |

| Regional unit | East Attica |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Giannis Kalafatelis (Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 69.36 km2 (26.78 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 21.41 km2 (8.27 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 480 m (1,570 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 40,193 |

| • Municipality density | 580/km2 (1,500/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 6,458 |

| • Municipal unit density | 300/km2 (780/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

| Postal code | 145 76 |

| Area code(s) | 210 |

| Vehicle registration | Z |

| Website | www.dimosdionysou.gr |

Dionysos (Greek: Διόνυσος) is a town and a municipality in northeastern Attica, Greece. The seat of the municipality is the town Agios Stefanos.[2]

Geography

Dionysos is situated on the northeastern slopes of the forested Penteliko Mountains. It is 5 km south of Agios Stefanos, 9 km west of Nea Makri, on the Aegean Sea coast, and 18 km northeast of Athens city centre. Its built-up area is continuous with those of the neighbouring suburbs Drosia and Rodopoli to the northwest. Even though the town is located only 20 Kilometres away from central Athens, it has a completely different climate, with weather being significantly cooler, including frequent snowfall during the winter.

Motorway 1 (Athens - Lamia - Thessaloniki) and the railway from Athens to Thessaloniki pass through the western part of the municipality, near Agios Stefanos. There is a railway station at Agios Stefanos. Dionysos is connected to Kifisia by the 536 Dionysos-Kifisia bus service.

Municipality

The municipality Dionysos was formed at the 2011 local government reform by the merger of the following 7 former municipalities, that became municipal units:[2]

The municipality has an area of 69.360 km2, the municipal unit 21.410 km2.[3]

History

The town was known by the Arvanitika name Tzamali (Τζαμάλη) up until 1928 when it was renamed Dionysos. The modern name of this small town on the north-east slopes of Mount Pendeli dates back to time immemorial, because this was the first demos (town) in ancient Attica (the province of which Athens is the major city) to welcome the young god Dionysos, ancient Greek god of vegetation, wine, and theatre.

The local myth is told by several ancient writers: Athenaios, Hyginos, Apollodoros, and Nonnos. In this green valley thousands of years ago, the local leader Icarius of Athens and his lovely daughter Erigone welcomed a young stranger into their home, offering him fresh goat’s milk as well as food and shelter. Moved by their warm hospitality, the stranger revealed to them that he was actually a god, Dionysos, son of Zeus (king of the gods) and Semele (a princess of Thebes). In order to thank them, Dionysos gave Ikarios the first grape vine and taught him the art of wine making.

Delighted with this wonderful drink which brought happiness and drowned sorrows, Ikarios filled several goatskin bags with wine and traveled around the countryside sharing the new drink with the local inhabitants. Unfortunately, some shepherds on Mount Pendeli drank too much of the magic drink, ‘unwatered’, and began to feel dizzy and see double. They suspected that Ikarios had poisoned them, and in their drunken state, they killed him.

When they awoke the next day and found Ikarios dead, they realized their terrible mistake. Fearfully they buried his body under a pine tree and ran away, some say to the island of Kea. The only witness to this crime was Erigone’s little dog, Maera, who ran home howling and pulled Erigone to the spot where her father had been buried and scratched at the soil. Realizing that her father was dead, Erigone fell into a deep depression and hung herself from a branch of the pine tree. Before she died, she or the god Dionysos called down a curse on the young women of Attika, that they should suffer the same fate as she had. The people of Athens were horrified when they began to find their daughters hanged from trees here and there and, ignorant of the cause, they appealed to the oracle of the god Apollo at Delphi to explain the deaths. The oracle directed them to find and properly bury the bodies of Ikarios and Erigone, and to track down and punish the murderers. Furthermore, the people were instructed to sacrifice the first grapes harvested every year to the memory of Ikarios and celebrate the ‘Αιωρα’ festival in honour of Erigone, when the young maidens would swing on swings under the trees and sing a song called the ‘αλητη’.

Out of this first tragic contact between the god Dionysos and the people of Attika, there arose the earliest Dioysiac worship, in the deme called Ikaria or Ikarion, the present day village of Dionysos. The local inhabitants continued to worship Dionysos for centuries in a festival which included drinking and feasting, singing and dancing, and parading round the village with a goat to sacrifice. In the 6th century BC, a local man named Thespis combined many of these elements into a new form of worshipful entertainment which he created, Τραγωοιδια or Tragedy. Every year in the month Poseidonia (early winter), the Ikarians would host the drama festival, "Τα Εν Αγροις Διονυσια’ (Rural Dionysia) to honour their favourite god, Dionysos. They even remembered the local heroes of the myth by putting them in the sky as constellations: Ikarios was the star Arcturus in the constellation Bootes, Erigone was Virgo, and Maera was the Lesser Dog Star, Procyon.

Although the deme of Ikaria was most famous for its worship of Dionysos, it was also well known for the high quality white marble quarried there, a reputation which it maintains even today. During the 5th and 4th centuries BC, all of Attika was divided into approximately 170 demes (villages), each of which sent one or more Βουλευτες (representatives) to the Βουλη (Council) of 500 to govern on a daily basis. The demes were then grouped into τριττυες, which in turn were combined to make ten Attic tribes based solely on a man’s residence, not any social status. Ikaria was such a large deme that it sent five (5) representatives annually to the Council of 500, and it belonged to the tribe Αεγεις, named after the Attic hero Aegeus who also gave his name to the Aegean Sea.

The archaeological site, to the left of Odos Bomou Dionysou heading towards Rapendosa in Dionysos, was the town center (εδρα) of ancient Ikarion and has many interesting features even today. To begin with, this spot was always associated with the name Dionysos and never lost its sacred nature. When worship of the ancient god ceased, a small Byzantine Christian church was built in the sanctuary and, as far as is known, it was dedicated to Saint Dionysios. It was rebuilt in the Middle Ages, but when Greece became a free nation once again (1821), it was already a ruin, destroyed during the Turkish occupation (1456-1821).

In 1886, a German traveler A. Milchhofer passed by and observed many ancient marble blocks built into the walls of the ruined Byzantine chapel.. He notified Dr. Merriam,the director of the newly formed American School of Classical Studies and excavations began on the site in January 1888 under the archaeologist Carl. D. Buck. Within weeks the site was securely identified as the center of the ancient deme of Ikarion, for the church walls yielded fragments of statues, inscriptions, and architectural elements from various buildings, all made of the local marble and dating from the classical period (5th and 4th century BC) and earlier. Among the most impressive finds are the cult statue of the god Dionysos himself, a superb marble work showing the god larger than life size seated on his throne holding his characteristic Boeotian kantharos drinking cup, and a marble relief stele of a ‘hoplite’ warrior which resembles the ‘Marathon Warrior’ stele and was used as the threshold stone for the church doorway. Both these treasures date from the end of the 6th century BC and are now on display in the archaic collection in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Even more information was provided by the many 4th-century BC inscriptions and choregic monuments discovered during two seasons of excavations. Of greatest interest was the large public marble stele (IG ii2 1178) which praised "the mayor (Nikon by name) and crowned him with Ivy (the plant of Dionysos) voted upon by the deme of the Ikarians, because he had fairly and justly carried out the Dionysiac festival" (a yearly drama contest). The stele goes on to praise the sponsors of the winning play as well. Because the sponsors who paid all the costs of producing the ancient plays for the contest were called ‘choregoi’, the monuments with their winning inscriptions are called choregic monuments. The existence of this and other choregic inscription steles verifies the identification of our site as the classical demos of Ikaria, and confirms as well the town’s reputation as host of the yearly "Dionysia" theatrical contests, where plays by the famous 5th-century BC dramatists Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were produced again and again alongside newer plays, thus assuring the "classical education" of all those who attended the festivals.

Pieces of sculpture and inscriptions are protected in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Following the slope of the hill was the seating area where the spectators at the ancient Dionysia sat to watch the plays taking place in the oblong orchestral area below, now defined by four fragments of marble thrones (K) for the priests at the bottom of the slope, and a row of stones (O) which supported the tent (σκηνη) behind which the actors changed, which also stood as the backdrop for the ‘orchestra’ (dance floor) where all acting took place. This theatrical area is downwards to the right as we enter the site from the modern road. To the left of the orchestra there is a large base (I) made of large and small slabs of marble set in the ground; This may be the base of the altar of the god Dionysos which always stood near or in an ancient theatre. Another possibility is that it was the altar of Apollo, whose temple (H) stood just to the left and is positively identified by its threshold block, a huge piece of marble inscribed ΙΚΑΡΙΩΝ ΤΟ ΠΥΘΙΟΝ, or ‘The Temple of Apollo of the Ikarians’. Just in front stand many bases for votive offerings (statues and inscriptions dedicated to the god) and inside the one room temple stands the base of the cult statue of Apollo, of which no trace has been found.

On the lower level of the site are the rest of the ancient foundations: to the left are the remains of the sanctuary wall (περιβολος)(E), in the center are two large marble bases (B&C)in front of a rectangular building(D), possibly for the cult statue and altar of Dionysos in front of his temple (no conclusive evidence), while to the right is a fairly well preserved foundation of a semi-circular choregic monument(A) dedicated by three sponsors (Αγνιας, Ξανθιππος, Ξανθιδης) whose play won in the Dionysia sometime in the first half of the 4th century BC. This monument was used for the apse of the Byzantine chapel which Milchofer found in ruins; a double throne from the theatre had also been brought over to provide seats outside the chapel door and it still stands there.

Considerable damage and weathering has occurred in the more than 100 years since the site was excavated, and a concerted effort by the Greek Archaeological Service is now getting under way to preserve and protect what remains on the site.[4]

Τhe Dionysia festival

Dionysos hosts an annual open summer festival usually every July, featuring art exhibitions, theatrical performances, musical shows, sculpture painting and other arts.

-

The old train station, site of the Dionysia Festival

-

Open air sculpture exhibition

Culture

The public library of Dionysos is located in the town hall, includes over 3500 books available to registered residents to borrow for free. It is run by local volunteers.

Gallery

-

The St. George Chiopolitis church in Dionysos

-

Penteli mountain as viewed from Dionysos

-

Typical street in Dionysos

Notable people

- Thespis (6th century BC) actor

See also

References

- ↑ "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- 1 2 Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (Greek)

- ↑ "Population & housing census 1991 (incl. area and average elevation)" (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece.

- ↑ Dionysos/Ikarion

External links

- Municipality of Dionysos

- White Marble of Dionissos-Penteli - greekmarble.com

- "White Marble of Dionissos-Penteli - marbleguide.gr". Archived from the original on 2005-02-09.

- Dionyssomarble group (Dionyssos - Pentelikon marble quarries)

- Dionissos White

|

Rodopoli |  | ||

| Ekali | |

Nea Makri | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Kifisia | Penteli |