Ernest Rutherford

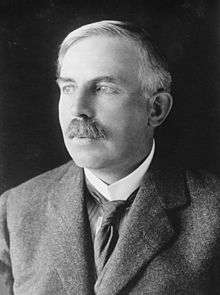

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, OM, FRS[1] (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.[2] Encyclopædia Britannica considers him to be the greatest experimentalist since Michael Faraday (1791–1867).[2]

In early work, Rutherford discovered the concept of radioactive half-life, proved that radioactivity involved the nuclear transmutation of one chemical element to another, and also differentiated and named alpha and beta radiation.[3] This work was done at McGill University in Canada. It is the basis for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry he was awarded in 1908 "for his investigations into the disintegration of the elements, and the chemistry of radioactive substances",[4] for which he is the first Canadian and Oceanian Nobel laureate, and remains the only laureate born in the South Island.

Rutherford moved in 1907 to the Victoria University of Manchester (today University of Manchester) in the UK, where he and Thomas Royds proved that alpha radiation is helium nuclei.[5][6] Rutherford performed his most famous work after he became a Nobel laureate.[4] In 1911, although he could not prove that it was positive or negative,[7] he theorized that atoms have their charge concentrated in a very small nucleus,[8] and thereby pioneered the Rutherford model of the atom, through his discovery and interpretation of Rutherford scattering by the gold foil experiment of Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden. He conducted research that led to the first "splitting" of the atom in 1917 in a nuclear reaction between nitrogen and alpha particles, in which he also discovered (and named) the proton.[9]

Rutherford became Director of the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge in 1919. Under his leadership the neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932 and in the same year the first experiment to split the nucleus in a fully controlled manner was performed by students working under his direction, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton. After his death in 1937, he was honoured by being interred with the greatest scientists of the United Kingdom, near Sir Isaac Newton's tomb in Westminster Abbey. The chemical element rutherfordium (element 104) was named after him in 1997.

Biography

Early life and education

Ernest Rutherford was the son of James Rutherford, a farmer, and his wife Martha Thompson, originally from Hornchurch, Essex, England.[10] James had emigrated to New Zealand from Perth, Scotland, "to raise a little flax and a lot of children". Ernest was born at Brightwater, near Nelson, New Zealand. His first name was mistakenly spelled 'Earnest' when his birth was registered.[11] Rutherford's mother Martha Thompson was a schoolteacher.[12]

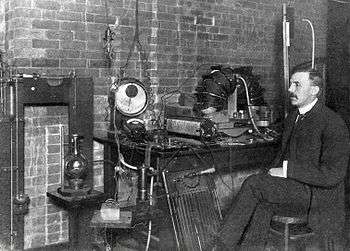

He studied at Havelock School and then Nelson College and won a scholarship to study at Canterbury College, University of New Zealand, where he participated in the debating society and played rugby.[13] After gaining his BA, MA and BSc, and doing two years of research during which he invented a new form of radio receiver, in 1895 Rutherford was awarded an 1851 Research Fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851,[14] to travel to England for postgraduate study at the Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge.[15] He was among the first of the 'aliens' (those without a Cambridge degree) allowed to do research at the university, under the inspiring leadership of J. J. Thomson, and the newcomers aroused jealousies from the more conservative members of the Cavendish fraternity. With Thomson's encouragement, he managed to detect radio waves at half a mile and briefly held the world record for the distance over which electromagnetic waves could be detected, though when he presented his results at the British Association meeting in 1896, he discovered he had been outdone by another lecturer, by the name of Marconi.

In 1898 Thomson recommended Rutherford for a position at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. He was to replace Hugh Longbourne Callendar who held the chair of Macdonald Professor of physics and was coming to Cambridge.[16] Rutherford was accepted, which meant that in 1900 he could marry Mary Georgina Newton (1876–1954)[17][18] to whom he had become engaged before leaving New Zealand; they had one daughter, Eileen Mary (1901–1930), who married Ralph Fowler. In 1900 he gained a DSc from the University of New Zealand. In 1907 Rutherford returned to Britain to take the chair of physics at the Victoria University of Manchester.

Later years and honours

He was knighted in 1914.[19] During World War I, he worked on a top secret project to solve the practical problems of submarine detection by sonar.[20] In 1916 he was awarded the Hector Memorial Medal. In 1919 he returned to the Cavendish succeeding J. J. Thomson as the Cavendish professor and Director. Under him, Nobel Prizes were awarded to James Chadwick for discovering the neutron (in 1932), John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton for an experiment which was to be known as splitting the atom using a particle accelerator, and Edward Appleton for demonstrating the existence of the ionosphere. In 1925, Rutherford pushed calls to the Government of New Zealand to support education and research, which led to the formation of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) in the following year.[21] Between 1925 and 1930 he served as President of the Royal Society, and later as president of the Academic Assistance Council which helped almost 1,000 university refugees from Germany.[2] He was appointed to the Order of Merit in the 1925 New Year Honours[22] and raised to the peerage as Baron Rutherford of Nelson, of Cambridge in the County of Cambridge in 1931,[23] a title that became extinct upon his unexpected death in 1937. In 1933, Rutherford was one of the two inaugural recipients of the T. K. Sidey Medal, set up by the Royal Society of New Zealand as an award for outstanding scientific research.[24][25]

For some time before his death, Rutherford had a small hernia, which he had neglected to have fixed, and it became strangulated, causing him to be violently ill. Despite an emergency operation in London, he died four days afterwards of what physicians termed "intestinal paralysis", at Cambridge.[26] After cremation at Golders Green Crematorium,[26] he was given the high honour of burial in Westminster Abbey, near Isaac Newton and other illustrious British scientists.[27]

Scientific research

At Cambridge, Rutherford started to work with J. J. Thomson on the conductive effects of X-rays on gases, work which led to the discovery of the electron which Thomson presented to the world in 1897. Hearing of Becquerel's experience with uranium, Rutherford started to explore its radioactivity, discovering two types that differed from X-rays in their penetrating power. Continuing his research in Canada, he coined the terms alpha ray and beta ray in 1899 to describe the two distinct types of radiation. He then discovered that thorium gave off a gas which produced an emanation which was itself radioactive and would coat other substances. He found that a sample of this radioactive material of any size invariably took the same amount of time for half the sample to decay – its "half-life" (11½ minutes in this case).

From 1900 to 1903, he was joined at McGill by the young chemist Frederick Soddy (Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1921) for whom he set the problem of identifying the thorium emanations. Once he had eliminated all the normal chemical reactions, Soddy suggested that it must be one of the inert gases, which they named thoron (later found to be an isotope of radon). They also found another type of thorium they called Thorium X, and kept on finding traces of helium. They also worked with samples of "Uranium X" from William Crookes and radium from Marie Curie.

In 1902, they produced a "Theory of Atomic Disintegration" to account for all their experiments. Up till then atoms were assumed to be the indestructable basis of all matter and although Curie had suggested that radioactivity was an atomic phenomenon, the idea of the atoms of radioactive substances breaking up was a radically new idea. Rutherford and Soddy demonstrated that radioactivity involved the spontaneous disintegration of atoms into other types of atoms (one element spontaneously being changed to another).

In 1903, Rutherford considered a type of radiation discovered (but not named) by French chemist Paul Villard in 1900, as an emission from radium, and realised that this observation must represent something different from his own alpha and beta rays, due to its very much greater penetrating power. Rutherford therefore gave this third type of radiation the name of gamma ray. All three of Rutherford's terms are in standard use today – other types of radioactive decay have since been discovered, but Rutherford's three types are among the most common.

In Manchester, he continued to work with alpha radiation. In conjunction with Hans Geiger, he developed zinc sulfide scintillation screens and ionisation chambers to count alphas. By dividing the total charge they produced by the number counted, Rutherford decided that the charge on the alpha was two. In late 1907, Ernest Rutherford and Thomas Royds allowed alphas to penetrate a very thin window into an evacuated tube. As they sparked the tube into discharge, the spectrum obtained from it changed, as the alphas accumulated in the tube. Eventually, the clear spectrum of helium gas appeared, proving that alphas were at least ionised helium atoms, and probably helium nuclei.

Gold foil experiment

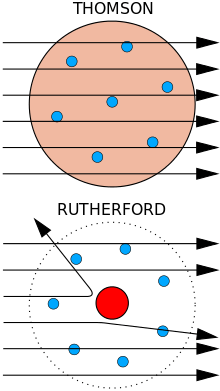

Bottom: Observed results: a small portion of the particles were deflected, indicating a small, concentrated charge. Note that the image is not to scale; in reality the nucleus is vastly smaller than the electron shell.

Rutherford performed his most famous work after receiving the Nobel prize in 1908. Along with Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden in 1909, he carried out the Geiger–Marsden experiment, which demonstrated the nuclear nature of atoms by deflecting alpha particles passing through a thin gold foil. Rutherford was inspired to ask Geiger and Marsden in this experiment to look for alpha particles with very high deflection angles, of a type not expected from any theory of matter at that time. Such deflections, though rare, were found, and proved to be a smooth but high-order function of the deflection angle. It was Rutherford's interpretation of this data that led him to formulate the Rutherford model of the atom in 1911 – that a very small charged [7] nucleus, containing much of the atom's mass, was orbited by low-mass electrons.

Before leaving Manchester in 1919 to take over the Cavendish laboratory in Cambridge, Rutherford became, in 1919, the first person to deliberately transmute one element into another.[4] In this experiment, he had discovered peculiar radiations when alphas were projected into air, and narrowed the effect down to the nitrogen, not the oxygen in the air. Using pure nitrogen, Rutherford used alpha radiation to convert nitrogen into oxygen through the nuclear reaction 14N + α → 17O + proton. The proton was not then known. In the products of this reaction Rutherford simply identified hydrogen nuclei, by their similarity to the particle radiation from earlier experiments in which he had bombarded hydrogen gas with alpha particles to knock hydrogen nuclei out of hydrogen atoms. This result showed Rutherford that hydrogen nuclei were a part of nitrogen nuclei (and by inference, probably other nuclei as well). Such a construction had been suspected for many years on the basis of atomic weights which were whole numbers of that of hydrogen; see Prout's hypothesis. Hydrogen was known to be the lightest element, and its nuclei presumably the lightest nuclei. Now, because of all these considerations, Rutherford decided that a hydrogen nucleus was possibly a fundamental building block of all nuclei, and also possibly a new fundamental particle as well, since nothing was known from the nucleus that was lighter. Thus, Rutherford postulated the hydrogen nucleus to be a new particle in 1920, which he dubbed the proton.

In 1921, while working with Niels Bohr (who postulated that electrons moved in specific orbits), Rutherford theorized about the existence of neutrons, (which he had christened in his 1920 Bakerian Lecture), which could somehow compensate for the repelling effect of the positive charges of protons by causing an attractive nuclear force and thus keep the nuclei from flying apart from the repulsion between protons. The only alternative to neutrons was the existence of "nuclear electrons" which would counteract some of the proton charges in the nucleus, since by then it was known that nuclei had about twice the mass that could be accounted for if they were simply assembled from hydrogen nuclei (protons). But how these nuclear electrons could be trapped in the nucleus, was a mystery.

Rutherford's theory of neutrons was proved in 1932 by his associate James Chadwick, who recognized neutrons immediately when they were produced by other scientists and later himself, in bombarding beryllium with alpha particles. In 1935, Chadwick was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery.

Legacy

Nuclear physics

Rutherford's research, and work done under him as laboratory director, established the nuclear structure of the atom and the essential nature of radioactive decay as a nuclear process. Rutherford's team, using natural alpha particles, demonstrated induced nuclear transmutation, and later, using protons from an accelerator, demonstrated artificially-induced nuclear reactions and transmutation. He is known as the father of nuclear physics. Rutherford died too early to see Leó Szilárd's idea of controlled nuclear chain reactions come into being. However, a speech of Rutherford's about his artificially-induced transmutation in lithium, printed in 12 September 1933 London paper The Times, was reported by Szilárd to have been his inspiration for thinking of the possibility of a controlled energy-producing nuclear chain reaction. Szilard had this idea while walking in London, on the same day.

Rutherford's speech touched on the 1932 work of his students John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton in "splitting" lithium into alpha particles by bombardment with protons from a particle accelerator they had constructed. Rutherford realized that the energy released from the split lithium atoms was enormous, but he also realized that the energy needed for the accelerator, and its essential inefficiency in splitting atoms in this fashion, made the project an impossibility as a practical source of energy (accelerator-induced fission of light elements remains too inefficient to be used in this way, even today). Rutherford's speech in part, read:

We might in these processes obtain very much more energy than the proton supplied, but on the average we could not expect to obtain energy in this way. It was a very poor and inefficient way of producing energy, and anyone who looked for a source of power in the transformation of the atoms was talking moonshine. But the subject was scientifically interesting because it gave insight into the atoms.[28]

Items named in honour of Rutherford's life and work

- Scientific discoveries

- The element rutherfordium, Rf, Z=104. (1997)[29]

- The rutherford (Rd), an obsolete unit of radioactivity equivalent to one megabecquerel.

- Institutions

- Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, a scientific research laboratory near Didcot, Oxfordshire.

- Rutherford College, Auckland, a school in Auckland, New Zealand

- Rutherford College, Kent, a college at the University of Kent in Canterbury, England

- Rutherford Institute for Innovation at the University of Cambridge

- Rutherford Intermediate School, Wanganui, New Zealand

- Rutherford Hall, a hall of residence at Loughborough University

- Awards

- Rutherford Medal, the highest science medal awarded by the Royal Society of New Zealand

- Rutherford Award at Thomas Carr College for excellence in Victorian Certificate of Education chemistry, Australia.

- Rutherford Memorial Medal is an award for research in the fields of physics and chemistry by the Royal Society of Canada.

- Rutherford Medal and Prize is awarded once every two years by the Institute of Physics for "distinguished research in nuclear physics or nuclear technology".

- Rutherford Memorial Lecture is an international lecture tour under the auspices of the Royal Society created under the Rutherford Memorial Scheme in 1952.

- Buildings

- Rutherford House, a boarding house at Nelson College[30]

- Rutherford Hotel, Nelson's largest hotel, which incorporates the Rutherford Cafe and Bar

- The physics and chemistry building at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand

- Rochester and Rutherford Hall at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand

- Rutherford House, the primary building of Victoria University of Wellington's Pipitea Campus, originally the headquarters of the New Zealand Electricity Department, in Wellington, New Zealand.

- Rutherford building at Bedford Modern School.

- A building of the modern Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge

- The Ernest Rutherford Physics Building at McGill University, Montreal[31]

- The Coupland Building at the University of Manchester, where Rutherford worked, was renamed "The Rutherford Building" in 2006.

- The Rutherford lecture theatre in the Schuster Laboratory at the University of Manchester

- Major streets

- Lord Rutherford Road (the location of his birthplace in Brightwater, New Zealand)

- Rutherford Street, a major thoroughfare in central Nelson, New Zealand

- Rutherford Close, a residential street in Abingdon, Oxfordshire

- Rutherford Road in the biotechnology district of Carlsbad, California

- Rutherford Road, commercial/residential street in Vaughan, Ontario, Canada

- Other

- Rutherford Park, a sports ground in Nelson, New Zealand

- The Rutherford Memorial at the site of his birth in Brightwater, New Zealand

- His image is on the obverse of the New Zealand one hundred-dollar note (since 1992).

- The Rutherford Foundation, a charitable trust set up by the Royal Society of New Zealand to support research in science and technology.[32]

- Rutherford House, at Macleans College, Auckland, New Zealand

- Rutherford House, at Hillcrest High School, Hamilton, New Zealand

- Rutherford House, at Rotorua Intermediate School, Rotorua, New Zealand

- Rutherford House, at Rangiora High School

- The crater Rutherford on the Moon, and the crater Rutherford on the planet Mars

- Ernest Rutherford was the subject of a play by Stuart Hoar.

- On the side of the Mond Laboratory on the site of the original Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, there is an engraving in Rutherford's memory in the form of a crocodile, this being the nickname given to him by its commissioner, his colleague Peter Kapitza.

- Rutherford rocket engine, an engine developed in New Zealand by Rocket Lab and the first to use the electric pump feed cycle.

- His image is depicted in the stained glass window of the Presbyterian chapel at Lindisfarne College in Hastings, New Zealand. The window, unveiled in 2007, is dedicated to the college's concept of men with supreme content of character, and depicts Rutherford along with Charles Upham, Edmund Hillary, and John Rangihau as iconic examples.

Incidences of cancer at Rutherford's former laboratory

The Coupland Building at Manchester University, at which Rutherford conducted many of his experiments, has been the subject of a cancer cluster investigation. There has been a statistically high incidence of pancreatic cancer, brain cancer, and motor neuron disease occurring in and around Rutherford's former laboratories and, since 1984, a total of six workers have been stricken with these ailments. In 2009, an independent commission concluded that the very slightly elevated levels of various radiation related to Rutherford's experiments decades earlier are not the likely cause of such cancers and ruled the illnesses a coincidence.[33]

Publications

- Radio-activity (1904), 2nd ed. (1905), ISBN 978-1-60355-058-1

- Radioactive Transformations (1906), ISBN 978-1-60355-054-3

- Radioactive Substances and their Radiations (1913)[34]

- The Electrical Structure of Matter (1926)

- The Artificial Transmutation of the Elements (1933)

- The Newer Alchemy (1937)

Articles

- "Disintegration of the Radioactive Elements" Harper's Monthly Magazine, January 1904, pages 279 to 284.

Styles of address and arms

Styles of address

- 1871-1903: Mr Ernest Rutherford

- 1903-1914: Mr Ernest Rutherford FRS

- 1914-1925: Sir Ernest Rutherford FRS

- 1925: Sir Ernest Rutherford OM FRS

- 1925-1930: Sir Ernest Rutherford OM PRS

- 1930-1931: Sir Ernest Rutherford OM FRS

- 1931-1937: The Right Honourable The Lord Rutherford of Nelson OM FRS

Arms

|

|

See also

References

- ↑ Eve, A. S.; Chadwick, J. (1938). "Lord Rutherford 1871–1937". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 2 (6): 394. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1938.0025.

- 1 2 3 "Ernest Rutherford, Baron Rutherford of Nelson". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "The Discovery of Radioactivity". lbl.gov. 9 August 2000.

- 1 2 3 "Ernest Rutherford – Biography". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ Campbell, John. "Rutherford – A Brief Biography". Rutherford.org.nz. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Rutherford, E.; Royds, T. (1908). "XXIV.Spectrum of the radium emanation". Philosophical Magazine Series 6. 16 (92): 313. doi:10.1080/14786440808636511.

- 1 2 Rutherford, Ernest (1911). The scattering of alpha and beta particles by matter and the structure of the atom. Taylor & Francis. p. 688.

- ↑ Longair, M. S. (2003). Theoretical concepts in physics: an alternative view of theoretical reasoning in physics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-0-521-52878-8.

- ↑ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

- ↑ McLintock, A.H. (18 September 2007). "Rutherford, Sir Ernest (Baron Rutherford of Nelson, O.M., F.R.S.)". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand (1966 ed.). Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-478-18451-8. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ↑ Campbell, John. "Rutherford, Ernest 1871–1937". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ By J.L. Heilbron - Ernest Rutherford And the Explosion of Atoms - Oxford University Press - ISBN 0-19-512378-6

- ↑ Campbell, John (30 October 2012). "Rutherford, Ernest". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara – The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ↑ 1851 Royal Commission Archives

- ↑ "Rutherford, Ernest (RTRT895E)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ McKown, Robin (1962). Giant of the Atom, Ernest Rutherford. Julian Messner Inc, New York. p. 57.

- ↑ TEARA:The Encyclopedia of New Zealand Story: Rutherford, Ernest

- ↑ Birth, Death and Marriage Historical Records, New Zealand Government Registration number 1954/19483

- ↑ The Edinburgh Gazette: no. 12647. p. 269. 27 February 1914.

- ↑ Alan Selby (2014-11-09). "Manchester scientist Ernest Rutherford revealed as top secret mastermind behind sonar technology". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

- ↑ Brewerton, Emma (2014-12-15). "Ernest Rutherford". Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- ↑ The Edinburgh Gazette: no. 14089. p. 4. 2 January 1925.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 33683. p. 533. 23 January 1931.

- ↑ "Background of the Medal". Royal Society of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Recipients". Royal Society of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- 1 2 The Complete Peerage, Volume XIII – Peerage Creations, 1901–1938. St Catherine's Press. 1949. p. 495.

- ↑ Heilbron, J. L. (2003) Ernest Rutherford and the Explosion of Atoms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 0-19-512378-6.

- ↑ The Times archives, 12 September 1933, "The British association – breaking down the atom"

- ↑ Freemantle, Michael (2003). "ACS Article on Rutherfordium". Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ↑ "Rutherford House". Nelson College. Nelson College. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ↑ "ErnestRutherford Physics Building". Virtual McGill. McGill University. 24 January 2000. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ↑ Lord Rutherford may have left a deadly legacy « Lord Rutherford may have left a deadly legacy « News « Royal Society of New Zealand. Royalsociety.org.nz. Retrieved on 26 January 2011.

- ↑ Brumfiel, Geoff (30 September 2009). "Rutherford Building cancers a 'coincidence'". doi:10.1038/news.2009.965.

- ↑ Carmichael, R. D. (1916). "Review" Radioactive Substances and their Radiations, by E. Rutherford" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 22 (4): 200. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1916-02762-5.

- ↑ Pais, Abraham (1999). Line of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 216. ISBN 0-19-851997-4.

- ↑ "Coat-of-Arms of Ernest Rutherford". Escutcheons of Science. Numericana.

Further reading

- Badash, Lawrence (2008) [2004]. "Rutherford, Ernest". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35891. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Cragg, R. H. (1971). "Lord ernest rutherford of nelson (1871?1937)". Royal Institute of Chemistry, Reviews. 4 (2): 129–120. doi:10.1039/RR9710400129.

- Campbell, J. (1999) Rutherford: Scientist Supreme, AAS Publications, Christchurch

- Marsden, E. (1954). "The Rutherford Memorial Lecture, 1954. Rutherford-His Life and Work, 1871–1937". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 226 (1166): 283–226. Bibcode:1954RSPSA.226..283M. doi:10.1098/rspa.1954.0254.

- Reeves, Richard (2008). A Force of Nature: The Frontier Genius of Ernest Rutherford. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-33369-8

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-44133-7

- Wilson, David (1983). Rutherford. Simple Genius, Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-23805-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ernest Rutherford. |

- Biography and web exhibit from the American Institute of Physics

- Biography from Nobel prize official website

- Nobel Lecture The Chemical Nature of the Alpha Particles from Radioactive Substances

- "Radioactive change", Rutherford & Soddy article (1903), online and analyzed on Bibnum [click 'à télécharger' for English version].

- The Rutherford Museum

- Rutherford Scientist Supreme

- Profile from American Public Broadcasting Service

- Profile from The New Zealand Edge

- Annotated bibliography for Ernest Rutherford from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Biography in 1966 An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

- Rutherford at Canterbury University College from The Rutherford Journal

- Rutherford's Timebomb Article on Rutherford's contribution to dating the Age of the Earth

- BBC Radio 4: In Our Time – Rutherford

- The Rutherford Collection at his alma mater the University of Canterbury

- Ernest Rutherford NZ Post stamp, 2008 – includes link to short biography and other sources (NZHistory.net.nz)

- Kennedy, Bruce. "Rutherford Gold Foil Experiment". Backstage Science. Brady Haran.

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| New creation | Baron Rutherford of Nelson 1931–1937 |

Extinct |