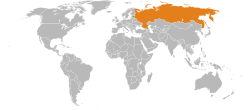

Estonia–Russia relations

|

|

Estonia |

Russia |

|---|---|

Estonia–Russia relations (Российско-эстонские отношения, Estonian: Eesti-Vene suhted) refers to bilateral foreign relations between Estonia and Russia. Diplomatic relations between the Republic of Estonia and the Russian SFSR were established on 2 February 1920, when Bolshevist Russia recognized de jure the independence of the Republic of Estonia, and renounced in perpetuity all rights to the territory of Estonia, via the Treaty of Tartu (Russian–Estonian). At the time, the Bolsheviks had just gained control of the majority of Russian territory, and their government's legitimacy was being hotly contested[1] by Western powers and the Russian White movement.

Estonia and Kievan Rus

.png)

In 1030 Yaroslav the Wise of Kievan Rus organised a military expedition to the territory of Ancient Estonia and built a fort he called Yuryev on the site of the Estonian stronghold of Tarbatu in Ugaunia, where Tartu is now located. In 1061, Estonians/Ugaunians took back the territories. During the reign of Yaroslav the Wise the first Russian Christian Churches were founded in Estonia. However, Estonia was not Christianised until the 13th century by German and Danish crusaders.[2]

Estonia and Tsardom of Russia

In 1558 Ivan IV of Russia invaded Livonian Confederation (the territory of the present-day Estonia and Latvia). Starting the Livonian War (1558–1582), a military conflict between the Tsardom of Russia and a coalition of Denmark, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Kingdom of Poland (later the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth), and Sweden. Treaty of Jam Zapolski in 1582 between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Russia renounced its claims to Livonia. The following year, the Tsar also made peace with Sweden. Under the Treaty of Plussa, Russia lost Narva and the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland, being its only access to the Baltic Sea. The situation was partially reversed 12 years later, according to the Treaty of Tyavzino which concluded a new war between Sweden and Russia.

Estonia and Russian Empire

Great Northern War

Sweden's defeat in the Great Northern War in 1721 resulted the Treaty of Nystad, the Russian Empire gained Sweden's Baltic territories Estonia (nowadays northern Estonia) and Livonia, (nowadays southern Estonia and northern Latvia). The legal system, Lutheran church, local and town governments, and education remained mostly German until the late 19th century and partially until 1918.

By 1819, the Baltic provinces were the first in the Russian Empire in which serfdom was abolished, the largely autonomous nobility allowing the peasants to own their own land or move to the cities. These moves created the economic foundation for the coming to life of the local national identity and culture as Estonia was caught in a current of national awakening that began sweeping through Europe in the mid-19th century.

Estonian Declaration of Independence

During World War I, between the retreating Russian and advancing German troops on 24 February 1918 the Salvation Committee of the Estonian National Council Maapäev issued the Estonian Declaration of Independence.

Estonia and Russian SFSR

Estonian War of Independence

The Estonian War of Independence (1918–1920), which took place during the Russian Civil War, was the Republic of Estonia's struggle for sovereignty in the aftermath of World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917. The war ended in 1920 with Estonia's victory over Russia.

Treaty of Tartu

The Treaty of Tartu was a peace treaty between Estonia and Russian SFSR signed on 2 February 1920 ending the Estonian War of Independence. According to this treaty, Russia (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic) recognized Estonia's sovereignty and renounced any and all territorial claims on Estonia.

Estonia and Soviet Union

Political relations

Comintern

In 1920 the rules were laid down in Russia at the Comintern's Second Congress, Communist parties abroad were to be created either afresh or else by splitting Social Democratic parties; in any case, they were to be accountable to Moscow and not to their domestic constituencies.[3]

Vladimir Lenin's incapacity and death (21 January 1924) triggered a struggle for power between Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin. During the struggle Soviet foreign policy drifted.

On 1 December 1924, Comintern conducted an attempted communist coup in Estonia.[4]

Treaties between Estonia and USSR

Before World War II, the Republic of Estonia and USSR had both signed and ratified following treaties:

- Kellogg–Briand Pact

- 27 August 1928 Kellogg–Briand Pact renouncing war as an instrument of national policy Ratified by Estonia and USSR on 24 July 1929[5]

- Non-aggression treaty

- Estonia, USSR on 4 May 1932[6]

- The Convention for the Definition of Aggression

- On 3 July 1933 for the first time in the history of international relations, aggression was defined in a binding treaty signed at the Soviet Embassy in London by USSR and among others, The Republic of Estonia.[7][8]

- Article II defines forms of aggression. There shall be recognized as an aggressor that State which shall be the first to have committed one of the following actions:

- Relevant chapters:

- Second– invasion by armed forces of the territory of another State even without a declaration of war.

- Fourth– a naval blockade of coasts or ports of another State.

Beginning of World War II

The fate of the relations between USSR and Republic of Estonia before World War II was decided by the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact and its Secret Additional Protocol of August 1939.

- 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland.

- 3 September, Great Britain, France, Australia, and New Zealand declared war on Germany

- 14 September, the Polish submarine ORP Orzeł reached Tallinn, Estonia

- 17 September, Soviet Union invaded Poland

- 18 September, Orzeł incident, the Polish submarine escaped from internment in Tallinn and eventually made her way to the United Kingdom, Estonia's neutrality was questioned by the Soviet Union and Germany.

- On 24 September 1939, warships of the Red Navy appeared off Estonian ports, Soviet bombers began a threatening patrol over Tallinn and the nearby countryside.[9] In light of the Orzeł incident, the Moscow press and radio started violently attacking Estonia as "hostile" to the Soviet Union. Moscow demanded that Estonia allow the USSR to establish military bases and station 25,000 troops on Estonian soil for the duration of the European war.[10] The government of Estonia accepted the ultimatum signing the corresponding agreement on 28 September. 1939.

The Pact was made for ten years:

- 1) Estonia granted the USSR the right to maintain naval bases and airdromes protected by Red Army troops on the strategic islands dominating Tallinn, the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Riga;

- 2) Soviet Union agreed to increase her annual trade turnover with Estonia and to give Estonia facilities in case the Baltic is closed to her goods for trading with the outside world via Soviet ports on the Black Sea and White Sea;

- 3) USSR and Estonia undertooke to defend each other from "aggression arising on the part of any great European power"

- 4) It was declared: the Pact "should not affect" the "economic systems and state organizations" of USSR and Estonia.[9]

Soviet annexation 1940

On 12 June 1940 the order for total military blockade of Estonia was given to the Soviet Baltic Fleet[11][12]

On 14 June, the Soviet military blockade of Estonia took effect. Two Soviet bombers downed a Finnish passenger airplane Kaleva flying from Tallinn to Helsinki and carrying three diplomatic pouches from the U.S. legations in Tallinn, Riga and Helsinki.[13]

On 16 June 1940, the Soviet Union invaded Estonia.[14] The Red Army exited from their military bases in Estonia, some 90,000 additional Soviet troops entered the country. Molotov had accused the Baltic states of conspiracy against the Soviet Union and delivered an ultimatum to Estonia for the establishment of a government the Soviets approve of. The Estonian government decided according to the Kellogg-Briand Pact not to use war as an instrument of national policy. Given the overwhelming Soviet force both on the borders and inside the country, not to resist, to avoid bloodshed and open war.[15]

On 17 June Estonia accepted the ultimatum and the statehood of Estonia de facto ceased to exist, the day France surrendered to Germany. The military occupation of the Republic of Estonia was complete by 21 June 1940 and rendered "official" by a communist coup d'état supported by the Soviet troops.[16]

Most of the Estonian Defence Forces and the Estonian Defence League surrendered according to the orders believing that resistance was useless and were disarmed by the Red Army. Only the Estonian Independent Signal Battalion stationed in Tallinn at Raua Street showed resistance. As the Red Army brought in additional reinforcements supported by six armoured fighting vehicles, the battle lasted several hours until sundown. There was one dead, several wounded on the Estonian side and about 10 killed and more wounded on the Soviet side. Finally the military resistance was ended with negotiations and the Single Signal Battalion surrendered and was disarmed.[17]

On the same day 21 June 1940 the flag of Estonia was replaced with a red flag on Pikk Hermann tower, the symbol of the government in Estonia in force.

14–15 July rigged "parliamentary elections" were held where all but pro-Communist candidates were outlawed. Those who failed to have their passports stamped for so voting were allowed to be shot in the back of the head.[18] Tribunals were set up to punish "traitors to the people." those who had fallen short of the "political duty" of voting Estonia into the USSR. The "parliament" so elected proclaimed Estonia a Socialist Republic on 21 July 1940 and unanimously requested Estonia to be "accepted" into the Soviet Union. Estonia was formally annexed into the Soviet Union on 6 August and renamed the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.[19] The 1940 occupation and annexation of Estonia into the Soviet Union was considered illegal and never officially recognized by Great Britain, the United States, Canada and other Western democracies.[20]

Soviet terror

During the first year of Soviet occupation (1940–1941) over 8,000 people, including most of the country's leading politicians and military officers, were arrested. About 2,200 of the arrested were executed in Estonia, while most others were moved to prison camps in Russia, from where very few were later able to return alive. On 19 July 1940 the Commander-in-chief of the Estonian Army Johan Laidoner was captured by the NKVD and deported together with his spouse to the Town of Penza. Laidoner died in the Vladimir Prison Camp, Russia on 13 March 1953.[21] President of Estonia, Konstantin Päts was arrested and deported by the Soviets to Ufa in Russia on 30 July, he died in a psychiatric hospital in Kalinin (now Tver) in Russia in 1956. 800 Estonian officers, i.e., about a half of the total were executed, arrested or starved to death in prison camps.

On 14 June 1941, when June deportation took place simultaneously in all three Baltic countries, about 10,000 Estonian civilians were deported to Siberia and other remote areas of the Soviet Union, where nearly half of them later perished. Of the 32,100 Estonian men who were forcibly relocated to Russia under the pretext of mobilisation into the Red Army after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, nearly 40 percent died within the next year in the "labour battalions" through hunger, cold and overworking. During the first Soviet occupation of 1940–41 about 500 Jews were deported to Siberia.

When Estonia was proclaimed a Soviet republic, the crews of 42 Estonian ships in foreign waters refused to return to homeland (about 40% of Estonian pre-war fleet) These ships were brought into requisition by the British powers and were used in the Atlantic convoys. During the time of the war, approximately 1000 Estonian seamen served at the British militarised merchant marine, 200 of them as officers. A small number of Estonians served in the Royal Air Force, in the British Army and in the US Army, altogether no more than two hundred.

Soviet repressions against ethnic Russians

Ethnic Russians in Estonia: Sergei Zarkevich, an activist of Russian organizations in Estonia, The owner of a book store "Russian Book": arrest order issued by NKVD on 23 June 1940, executed on 25 March 1941. Oleg Vasilovski, a former General in the Russian Imperial Army. Arrest order issued by NKVD on 1 July 1940. Further fate unknown. Sergei Klenski, one of the former leaders of the Russian Peasants Labor Party. Arrested on 22 July. On 19 November 1940, sentenced to 8 years in a prison camp. Further fate unknown. Mikhail Aleksandrov, Arseni Zhitkov.[22] Other ethnic Russians in Estonia arrested and executed by different Soviet War Tribunals in 1940–1941. Ivan Salnikov, Pavel Mironov, Mihhail Arhipov, Vassili Belugin, Vladimir Strekoytov, Vasili Zhilin, Vladimir Utekhin, Sergei Samennikov, Ivan Meitsev, Ivan Yeremeyev, Konstatin Bushuyev, Yegor Andreyev, Nikolai Sausailov, Aleksandr Serpukhov, Konstatin Nosov, Aleksandr Nekrasov, Nikolai Vasilev-Muroman, Aleksei Sinelshikov, Pyotr Molonenkov, Grigory Varlamov, Stepan Pylnikov, Ivan Lishayev, Pavel Belousev, Nikolai Gusev, Leonid Sakharov, Aleksander Chuganov, Fyodor Dobrovidov, Lev Dobek, Andrei Leontev, Ivan Sokolov, Ivan Svetlov, Vladimir Semenov, Valentin Semenov-Vasilev, Vasili Kamelkov, Georgi Lokhov, Aleksei Forlov, Ivan Ivanov, Vasili Karamsin, Aleksandr Krasilnikov, Aleksandr Zhukov, etc. Full list at:[23]

Soviet occupation 1944–1991

Soviet forces reconquered Estonia in the autumn of 1944 after fierce battles in the northeast of the country on the Narva river and on the Tannenberg Line (Sinimäed). In 1944, in the face of the country being re-occupied by the Red Army, 80000 people fled from Estonia by sea to Finland and Sweden, becoming war refugees and later, expatriates. 25,000 Estonians reached Sweden and a further 42,000 Germany. During the war about 8 000 Estonian Swedes and their family members had emigrated to Sweden. After the retreat of Germans, about 30,000 Estonian partisans remained in hiding in the Estonian forests, further on leading a massive guerrilla war. In 1949 27,650 Soviet troops still led the war against the local partisans. Only the 1949 mass deportation when about 21,000 people were taken away broke the basis of the partisan movement. 6600 partisans gave themselves up in November 1949. Later on the failure of the Hungarian uprising broke the resistance morale of the 700 men still remaining under cover. According to the Soviet data, up to 1953, 20,351 partisans were disarmed. Of these, 1510 perished in the battles. During that period, 1 728 members of the Red Army, NKVD and the militia were killed by the "forest brothers". August Sabbe, the last surviving Forest Brother in Estonia, was discovered and killed[24] by KGB agents in 1978.

During the first post-war decade of Soviet regime, Estonia was governed by Moscow via Russian-born Estonian governors. Born into the families of native Estonians in Russia, the latter had obtained their Red education in the Soviet Union during the Stalinist repressions at the end of the 1930s. Many of them had fought in the Red Army (in the Estonian Rifle Corps), few of them had mastered the Estonian language.[25]

Although the United States and the United Kingdom, the allies of the USSR against Germany during World War II, recognized the occupation of the Republic of Estonia by USSR at Yalta Conference in 1945 de facto, the governments of the rest of the western democracies did not recognize the seizure of Estonia by the USSR in 1940 and in 1944 de jure according to the Sumner Welles' declaration of 23 July 1940;[26][27][28] such countries recognized Estonian diplomats and consuls who still functioned in many countries in the name of their former governments. These ageing diplomats persisted in this anomalous situation until the ultimate restoration of Estonia's independence in 1991.[29]

On 23 February. 1989 The red-blue waved flag of the Estonian SSR was lowered on Pikk Hermann. It was replaced with the blue-black-white flag of Estonia on 24 February 1989.

The first freely elected parliament during the Soviet era in Estonia had passed independence resolutions on 8 May 1990, and renamed Estonian SSR to the Republic of Estonia. During the attempted coup on 20 August 1991 by the Gang of Eight, the Estonian parliament issued the Declaration of Independence from the Soviet Union at 23:03 Tallinn time. On 6 September 1991, the State Council of the Soviet Union recognized the independence of Estonia.,[30] immediately followed by the international recognitions of the Republic of Estonia.

In 1992, Heinrich Mark, the Prime Minister of the Republic of Estonia in duties of the President in exile,[31] presented his credentials to the newly elected President of Estonia Lennart Meri.

The last Russian troops withdrew from Estonia in August 1994.[32]

Estonia and Russian Federation

Russian-Estonian relations were re-established in January 1991, when the presidents Boris Yeltsin of Russian SFSR and Arnold Rüütel of Estonia met in Tallinn and signed a treaty governing the relations of the two countries after the anticipated independence of Estonia from the Soviet Union.[33][34] The treaty guaranteed the right to freely choose their citizenship for all residents of the former Estonian SSR.

Russia re-recognized the Republic of Estonia on 24 August 1991, after the failed Soviet coup attempt, as one of the first countries to do so. Diplomatic relations were established on 24 October 1991. The Soviet Union recognized the independence of Estonia on 6 September.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, the Russian Federation became an independent country. Russia was widely accepted as the Soviet Union's successor state in diplomatic affairs[35] and it assumed the USSR's permanent membership and veto in the UN Security Council; see Russia's membership in the United Nations.

Estonia's ties with Boris Yeltsin weakened since the Russian leader's initial show of solidarity with the Baltic states in January 1991. Issues surrounding the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Baltic republics and Estonia's denial of automatic citizenship to persons who settled in Estonia in 1941–1991 and their offspring[36] ranked high on the list of points of contention.

Withdrawal of Russian troops

Immediately after regaining the independence, Estonia started to insist that the Soviet Union (and later Russia) should withdraw their troops from Estonian territory and that the process should be completed by the end of the year. The Soviet government responded that withdrawal could not be completed before 1994 due to lack of available housing.

In the fall of 1991 the Soviet Union claimed Estonia's new citizenship policy, still in the process of being developed, was a violation of human rights. Under the citizenship policy, most of the country's large (mainly Russophone) minority of Soviet immigrants arriving between 1941 and 1991, as well as their offspring, were denied automatic citizenship. They could gain citizenship through a naturalisation process that included tests on Estonian and the constitution, as well as a long-time residency requirement. The Soviet government linked further withdrawal of troops from Estonia to a satisfactory change in Estonia's citizenship stance. In response, Estonia denied the accusations of violations of human rights and invited more than a dozen international fact-finding groups to visit the country for verification. In January 1992, some 25,000 Russian troops were reported left in Estonia, the smallest contingent in the Baltic states. Still, more than 800 square kilometres of land, including an inland artillery range, remained in the Russian military's hands. More than 150 battle tanks, 300 armored vehicles, and 163 military aircraft also remained.

On 1 July 1993, angered by Estonia's Aliens Act, Russia's Supreme Soviet passed a resolution “on measures in connection with the violation of human rights on the territory of the Estonian Republic”, calling for sanctions against Estonia, including a complete halt of the troops pullout.[37]

As the propaganda war and negotiations dragged on, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania gained international support for their position on troop withdrawal at a July 1992 summit of the CSCE in Helsinki. The final communiqué called on Russia to act "without delay... for the early, orderly and complete withdrawal" of foreign troops from the Baltic states. Resolutions also were passed in the United States Senate in 1992 and 1993 linking the issue of troop withdrawals to continued United States aid to Russia.

Yet, Estonian and Russian negotiators remained deadlocked throughout 1993. At several points, President Yeltsin and other Russian officials called an official halt to the pullout, but the unofficial withdrawal of forces continued. By the end of 1992, about 16,000 troops remained. A year later, that number was down to fewer than 3,500, and more than half of the army bases had been turned over to Estonian defense officials. The Estonian and Russian sides continued to disagree, primarily over the pace of Russia's withdrawal from the town of Paldiski, on the northern coast some thirty-five kilometers west of Tallinn. The Soviet navy had built a submarine base there that included two nuclear submarine training reactors. Russian officials maintained that dismantling the reactor facility would take time; Estonia demanded faster action along with international supervision of the process.

It was not until 31 August 1994 that the last Russian troops left Estonia, as Presidents Boris Yeltsin and Lennart Meri had signed an agreement on 26 July 1994 for the complete withdrawal of Russian troops. The last Russian warship, carrying ten T-72 tanks, departed in August 1994. However, Russia was to retain control of the reactor facility in Paldiski until September 1995. On 30 September 1995 the decommissioning of the Paldiski nuclear base was completed.

Controversies

During Perestroika, the reassessment era of Soviet history in USSR, in 1989 the USSR condemned the 1939 secret protocol between Nazi Germany and itself that had led to the invasion and occupation of the three Baltic countries.[38] The collapse of the Soviet Union led to the restoration of the Republic of Estonia's sovereignty (See History of Estonia: Regaining independence.) According to the Government of Estonia,[39] the European Court of Human Rights,[40] EU,[41] USA[42] Estonia remained occupied by the Soviet Union until restoration of its independence in 1991 and the 48 years of Soviet occupation and annexation was never recognized as legal by the Western democracies.

Russian government and officials continue to maintain that the Soviet annexation of the Baltic states was legitimate[43] and that the Soviet Union liberated the countries from the Nazis[44] They state that the Soviet troops had entered the Baltic countries in 1940 following the agreements and with the consent of the governments of the Baltic republics. They maintain that the USSR was not in a state of war and was not waging any combat activities on the territory of the three Baltic states, therefore, the argument goes, the word 'occupation' can not be used.[45][46] "The assertions about [the] 'occupation' by the Soviet Union and the related claims ignore all legal, historical and political realities, and are therefore utterly groundless." (Russian Foreign Ministry)

However the fact was that consent was coerced after Soviet troops were massed on the border. The Soviet 8th army was dispatched to Pskov on 14 September 1939, and the mobilized 7th army placed under the Leningrad Military District. On 26 September, the Leningrad Military District was ordered to "start concentrating troops on the Estonian-Latvian border and to finish that operation on 29 September." The order noted, "for the time of starting the attack a separate directive will be issued."[47] Altogether, by the beginning of October 1939, the Soviets had amassed along the Estonia-Latvia border:

- 437,325 troops

- 3,635 artillery pieces

- 3,052 tanks

- 421 armored vehicles

- 21,919 cars[48]

According to the American author Thomas Ambrosio, the core of the current controversies lay in the Kremlin's rhetorical response to external criticisms of Russia's own democratic and human rights record, where Moscow's harsh denunciations of Estonia which are far disproportionate to Tallinn's actual policies, are intended to put the West on the defensive rather than describe the realities within Estonia[49] Russia has made three general claims based upon exaggeration or outright misrepresentation as a part of their "accuse" strategy: the human rights of the Russian-speakers were being violated; Estonia has a "democratic deficit" because it did not allow non-citizens to vote in national elections; and that rejecting the legitimacy of the Soviet occupation was equivalent to glorifying Nazism.[49]

Language and citizenship issues

During the Soviet period the share of Russophones in Estonia increased from less than a tenth to over a third, and to almost half in the capital Tallinn, and even to a majority in some districts in North East Estonia. (See Demographics of Estonia and Estonian SSR: Demographic changes.) In contrast to the long-standing pre-World War II Russian minority in Estonia, these were Soviet economic migrants. Russian was an official language in parallel to, and in practice often instead of, Estonian in Estonian SSR and there were no integration efforts during the Soviet time, resulting in considerable groups of people knowing very little or no Estonian.

After Estonia re-established independence, Estonian again became the only official language.

The mass deportations of ethnic Estonians during the Soviet era together with migration into Estonia from other parts of the Soviet Union resulted in the share of ethnic Estonians in the country decreasing from 88% in 1934 to 62% in 1989.[50] (See Demographics of Estonia.) In 1992, the Citizenship Act[51] of the Republic of Estonia was reinstated according to the pre-Soviet invasion status quo in 1940. Throughout the years of occupations (the major democracies of the world never accepted the forcible incorporation of the Baltic States by the USSR in 1940), the pre-Soviet invasion Estonian citizens and their descendants never lost their citizenship, regardless of their ethnic origin, be it Estonian, Russian (8.2% of the citizenry by the 1934 census[52]), German or any other, according to the jus sanguinis principle. Conditions for acquiring and receiving Estonian citizenship for post-1940 settlers and their descendants in Estonia are an examination in knowledge of the Estonian language and an examination in knowledge of the Constitution of Estonia and the Law. Applicants for Estonian citizenship who were born prior to 1 January 1930, or hearing or speech disabled, permanently disabled, et cetera, are exempt from the requirements.

Currently about a third of Estonia's Russophones are Estonian citizens, another third have Russian citizenship. At the same time in 2006 around 9% of Estonia's residents were of undefined citizenship. While there have been calls for the return of all Estonia's Russians to Russia,[53] the Government of Estonia has been adopting an integration policy, advocating an idea that Estonia's residents should possess at least a basic knowledge of the Estonian language.[54]

People who arrived in the country after 1940 qualify for naturalization if they have general knowledge of Estonian language and the Constitution, have legally resided in Estonia for at least eight years, the last five of them permanently, have a registered place of residence in Estonia and a permanent legal income.[55] Russia has repeatedly condemned Estonian citizenship laws and demanded that Estonia grant its citizenship without (or by a greatly simplified) naturalization procedure. The perceived difficulty of the language tests necessary for naturalisation has been one of the controversial issues.

In February 2002, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Yevgeni Gussarov presented to Estonian ambassador Karin Jaani a non-paper list of seven demands to be fulfilled by Estonia in order to improve the relations of the two countries. These demands included making Russian an official language in the regions where the russophone minority was actually a majority, granting citizenship by naturalization to at least 20,000 residents annually, stopping prosecuting the persons who had been involved in the deportation of Estonians, official registering the Russian Orthodox Church, providing secondary and higher education in Russian language.[56]

Accusations of fascism

There have been various allegations of fascism (i.e., Nazism in Soviet speech), glorification of Nazism and Estonia's collaboration with Germans in World War II, resurrection of Nazism and being pro-Nazi against Estonia by official spokesmen and Jewish religious leaders of Russia, as well as by international spokesmen and associations, including René van der Linden and Efraim Zuroff.[57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65]

According to Economist: What really annoys the Kremlin is that Estonians regarded the arrival of the Red Army in 1944–45 as the exchange of one ghastly occupation for another instead of a liberation.[66] The Estonian Education Minister Tõnis Lukas has said "We do not glorify the Nazis in any way, but Moscow seems very upset that Estonia considers the Nazi era and Stalinism as equally evil and criminal regimes."[67]

A controversial monument had been erected by a private group in the seaside town of Pärnu in 2002. It honoured Estonian soldiers who fought the Red Army during World War II and was reported as "SS monument" by some news agencies, including BBC.[68] The Monument hadn't been formally unveiled and had been taken down shortly afterward amid criticisms of the international community. In 2004 the same monument was re-erected in the town of Lihula, however it was removed by the Estonian government after 9 days[69] amid violent protests from some monument supporters. The monument depicts an Estonian soldier in a German-type military uniform, and according to a journalist of the Baltic Times, with a Waffen-SS (combat SS) unit emblem.[70] However a semiotic analysis by professor Peeter Torop of University of Tartu, consulting for the Lihula police department, concluded that no Nazi or SS symbolics whatsoever appear in the bas-relief.[71][72]

There are legitimate organizations representing Waffen SS veterans in Estonia, and former Waffen SS soldiers are paid pensions by the German government.[63] While the Nuremberg Trials condemned the Waffen-SS as part of a criminal organisation, conscripts were exempted from that judgment due to being involuntarily mobilized. Conscripting natives of occupied territory is considered a war crime under the Geneva Convention. The 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian) is an example of such a conscript formation, the units cannot be accused of committing crimes against humanity.[73][74]

According to The New York Times: "Many Russians have accused countries once under the Kremlin’s sway, including Estonia, of not pursuing a full account of some of their citizens’ collaborations with the Nazis."[75] Martin Arpo, superintendent of Security Police Board disagrees with this Russian view, saying "Both regimes were criminal and committed criminal acts and brought suffering to the Estonian people. But the local K.G.B. couldn’t find any more evidence against the Nazi collaborators. We haven’t found it either. And the K.G.B. was a much larger organization than we are and had powers and methods, shall we say, that are not available to a Western democratic country."[75]

Accusations of Human rights violations

The Government of Russia, claimed (in 2005) that "there is discrimination against the Russian-speaking minority (not only ethnic Russians but also Russian-speaking Jews)."[76] The Federal Migration Service of Russia has supported a law that would set a language test for anyone planning to work in Russia for more than one year. "It is obvious that without knowledge of the Russian language it is impossible to integrate into Russian society," the Russian Migration Service has said.[77] The Russian law applies to new immigrants. With the restoration of Estonian independence in 1991 the Citizenship Law of 1938, based on the principle of jus sanguinis, came into force. Consequently, all Soviet immigrants who had moved into Estonian SSR, when Estonia was under Soviet occupation in 1940–1941 and 1944–1991, as well as to their descendants born before 1992 found themselves with neither Estonian nor Russian citizenship. Non-citizen parents can request expedited citizenship for their children born after 1992 if they have been residents of Estonia for five years. Continuity of citizenship applied automatically to Russophones who were citizens or descendants of citizens of Republic of Estonia prior 1940.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities have declared that they cannot find a pattern of human rights violations or abuses in Estonia.[78]

However, the European Centre for Minority Issues has also criticised what is sees as Estonia's harsh treatment of its Russian population, and has condemned the ostensible lack of legal protection offered to minorities.[79] The forum Development and Transition, which is sponsored by the United Nations, published an article in its newsletter on November 2005 where Professor James Hughes argues that Latvia and Estonia employ a "sophisticated and extensive policy regime of discrimination" against their respective Russophone parts of the population.[80] However, in that same newsletter Professor Hughes arguments were opposed by former Latvian minister for social integration Dr. Nils Muiznieks who argued his views were simplistic and "similar to what Russian propaganda has been touting in international fora over the last 10 years".[81]

Although the OSCE and other international organizations, such as the Finnish Helsinki Committee, have found the Citizenship Law to be satisfactory, the Russian Government and members of the local ethnic Russian community continued to criticize it as discriminatory, notably for its Estonian language requirements. In September 2003, a visiting NATO Parliamentary Assembly delegation concluded that the country had no major problems in treatment of its Russian minority.[82]

Dr. Kara Brown has claimed in her 1997 report at Indiana University newsletter that "the Russian government, disregarding the fact that Estonia's Russian speakers willingly have chosen to stay [in Estonia], has used the excuse of alleged minority-right infringements as justification for a possible armed invasion.[83] She suggested that, once in Estonia, these Russian troops would 'secure' the rights of these Russian-speakers who live outside of their homeland. According to K. Brown this vow of 'support' only aggravates attempts being made by the Russian speakers to solve their political problems independently and jeopardizes the development of healthy foreign relations between Estonia and Russia. However, this "Russian Plan for Invasion of the Baltic States," (as published in The Baltic Independent in 1995),[84] had never been implemented, nor its authenticity had been confirmed by the independent sources. Estonian media have repeatedly claimed that Russian politicians called for military action against Estonia to protect the "compatriots", most recently this accusation had been fielded against Dmitry Rogozin[85] during the Bronze Soldier crisis.

In 2005, the Estonian Prime Minister Juhan Parts expressed concerns about alleged Russian violations of human and cultural rights of the Mari people,[86] who are ethnically related to the Estonian people. Estonian Institute for Human Rights claims Russia persecutes Mari journalists and oppositions leaders. Several journalists have been killed while in the cultural sphere TV and radio programmes in Mari language in the autonomous Republic of Mari El are restricted to a minimum of a brief news segment on the TV and Mari language radio broadcasting has been severely curtailed as well.[87] The EU subsequently passed a resolution strongly condemning the violations of human rights by the Russian authorities in Mari El.[88]

Other issues

Orthodox Church controversy

A legal dispute went on between the Tallinn and Moscow governments since 1993, when the Estonian government re-registered the Estonian Orthodox Church under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical (Constantinpole) Patriarchate. This made it impossible to register the Estonian Orthodox Church of Moscow Patriarchate, which had collaborated with the Soviet occupation. The main issue was, which of the two owned the property of the Orthodox church in Estonia, held by the Moscow Patriarchate until 1923, then by the Church under the Ecumenical Patriarchate until the Soviet occupation of Estonia in 1940, and consequently handed to the Moscow Patriarchate by the Soviet government.[89] Estonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate was registered in Estonia in April 2002.

Territorial issues

Territorial issues also clouded Estonian-Russian relations. Estonia had hoped for the return of more than 2,000 square kilometers of territory annexed to Russia by Stalin in 1945. The annexed land had been within the borders Estonia approved by Russia in the 1920 Tartu Peace Treaty. However, the Yeltsin government disavowed any responsibility for acts committed by the Soviet regime.

Estonian and Russian negotiators reached a technical border agreement in December 1996, with the border remaining substantially the same as the one drawn by Stalin, with some minor adjustments. The border treaty was initialed in 1999. On 18 May 2005 Estonian Foreign Minister Urmas Paet and his Russian colleague Sergei Lavrov signed in Moscow the “Treaty between the Government of the Republic of Estonia and the Government of the Russian Federation on the Estonian-Russian border” and the “Treaty between the Government of the Republic of Estonia and the Government of the Russian Federation on the Delimitation of the Maritime Zones in the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Narva”. The Riigikogu (Estonian Parliament) ratified the treaties on 20 June 2005, with a reference to the 1920 Tartu Peace Treaty in the preamble of the ratification law, placing the new border treaty in context of internal Estonian law as amending the original 1920 border. The President of Estonia Arnold Rüütel proclaimed the treaties on 22 June 2005. As proposed by the Russian Government on 13 August 2005,[90] on 31 August 2005 Russian President Vladimir Putin gave a written order to the Russian Foreign Ministry to notify the Estonian side of “Russia’s intention not to participate in the border treaties between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Estonia”. On 6 September 2005 the Foreign Ministry of the Russian Federation sent to Estonia a note, in which Russia informed that it did not intend to become a party to the border treaties between Estonia and Russia and did not consider itself bound by the circumstances concerning the object and the purposes of the treaties. Negotiations were reopened in 2012 and the Treaty was signed in February 2014. Ratification is pending.[91]

- This section contains material[92] from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain.

Russia's attitude to Estonian accession to the NATO and the EU

When the Baltic states restored their independence in 1991 they demanded withdrawal of the Russian troops from their territory, where USSR has built various military installations. Later in the 1990s the Baltic states refused Russia's proposals of security guaranties in favor of NATO alliance.[93][94] NATO, particularly its expansion, is considered a threat in Russia.

Bronze Soldier of Tallinn controversy

The relocation of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn and exhumation of the bodies buried from a square in the center of Tallinn to a military cemetery in April 2007 provoked a harsh Russian reaction. The Federation Council, on 27 April, approved a statement concerning the monument, which urges the Russian authorities to take the "toughest possible measures" against Estonia.[95] First Deputy Prime Minister Sergey Ivanov said that adequate measures, primarily, economic ones, should be taken against Estonia.[96] Belittling the World War II heroes' feats and desecrating monuments erected in their memory leads to discord and mistrust between countries and peoples, Russian President Vladimir Putin said on Victory Day 2007.[97] In the days following the relocation, the Embassy of Estonia in Moscow was besieged by protesters, including pro-Kremlin youth organisations Nashi and the Young Guard of United Russia. Estonia's president Toomas Hendrik Ilves expressed his astonishment that Russia has — despite the promises of foreign minister Lavrov — not taken actions to protect the diplomatic personnel. On 2 May, a small group of protesters attempted to disrupt a press conference the Estonian ambassador to Russia, Marina Kaljurand was holding at the offices of the Moscow newspaper, Argumenty i Fakty, but were held back by security guards. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that the Ambassador confirmed to them that her bodyguard used pepper spray against the protesters.[98] Estonian foreign minister Urmas Paet suggested to consider calling off the upcoming EU-Russia Summit that was due to take place on 18 May).[99][100]

Railway works

On 3 May 2007, Russia announced plans for repairs to railway lines to Estonia, disrupting oil and coal exports to Estonian ports.[101] In July Russian Minister of Transport Igor Levitin announced that Russia was planning to stop all oil transit through Estonian ports and use Russian ports instead.[102]

Cyberattacks on Estonia

A series of distributed denial of service cyber attacks began on 27 April 2007 that swamped websites of Estonian organizations, including Estonian parliament, banks, ministries, newspapers and broadcasters, amid the Estonian-Russian row about the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn relocation. Estonian officials accused Russia of unleashing cyberwar.[103]

Exhibition dedicated to the Ukrainian Insurgent Army

An exhibition dedicated to the Ukrainian Insurgent Army opened in Tallinn in October 2009 was heavily criticised by Russian embassy in Estonia. "The UPA acted like war criminals and not as fighters for freedom as they are being portrayed in retrospect. We spoke of our negative view on the exhibition opened by the Estonian Foreign Ministry and voiced our reasons", Russian Embassy Press Attache Maria Shustitskaya told Estonian television.[104]

Meetings

Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves met in Khanty-Mansiysk in June 2008 at the 5th World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples, marking the first meeting between leaders of the two states in fourteen years.[105] On the meeting between the two presidents, Sergey Prikhodko, Aide to the Russian President, stated that "(t)here have been much warmer meetings. During the meeting, Ilves stated that rhetoric from both countries should be toned down, with Medvedev responding by saying that the Estonian President often made harsh statements against Russia, whereas he did not do the same about Estonia.[105][106] In his speech at the Congress, Ilves states “Freedom and democracy were our choice 150 years ago. Even poets didn’t dream about state independence at that time. Many Finno-Ugric peoples haven’t made their choice yet.” This led Russian representatives to believe that Ilves was calling for the breakup of the Russian state. Konstantin Kosachev, the Chairman of the International Affairs Committee in the State Duma, in response stated that Estonia and the European Parliament had demanded investigations into the 2005 attacks on a Mari activist, and had used the attack as evidence of discrimination of the Mari people in Russia, yet ignored calls for investigations on attacks on ethnic Russians, which included the murder of one, in the wake of the Bronze Soldier controversy.[106] Kosachev's speech led Ilves and the rest of the Estonian delegation to leave the conference hall in protest.[106] Ilves later stated that "to read into the speech anything requires a hyperactive and distorted imagination".[107]

Abduction of Estonian security official

On 5 September 2014 Estonian Internal Security Service official Eston Kohver was abducted at gunpoint from the border near the Luhamaa border checkpoint by Russian forces and taken to Russia. The abduction was preceded by jamming of Estonian communications and the use of a smoke grenade. Estonia also found evidence that a struggle had taken place.[108] President Toomas Hendrik Ilves called the incident "unacceptable and deplorable". The incident occurred during the ongoing invasion of Ukraine and following a visit to Estonia by US President Barack Obama. Russia admitted that they have detained Kohver, but claimed that he was in Russian territory at the time he was taken.[109][110] In August 2015 he was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

On 26 September 2015, an exchange deal between Russian and Estonian governments was made: Kohver was handed over to Estonia for convicted Russian spy Aleksei Dressen.[111][112]

Public opinion

According to Levada Center data, in 2007, Estonia was considered an enemy of Russia by 60 percent of Russia's citizens (cf. 28% in 2006, 32% in 2005), more than any other country in the world, followed by Georgia, Latvia and United States.[113] The poll was conducted two weeks after the Bronze Soldier relocation to a military cemetery and exhumation of the bodies buried there.

See also

References

- ↑ "William Henry Chamberlin. Soviet Russia: A Living Record and a History". Marxists.org. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Estonian Institute www.einst.ee". Einst.ee. 24 February 1918. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "Mike Jones: How Estonia became part of the USSR". Marxists.org. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Kellogg-Briand Pact at Yale University

- ↑ League of Nations Treaty Series, Vol. CXXXI, pp. 297–307.

- ↑ Aggression Defined at Time magazine

- ↑ League of Nations Treaty Series, 1934, No. 3391.

- 1 2 Moscow's Week at Time on Monday, 9 October 1939

- ↑ The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by David J. Smith, Page 24, ISBN 0-415-28580-1

- ↑ Pavel Petrov] at Finnish Defence Forces home page

- ↑ documents published Archived 5 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. from the State Archive of the Russian Navy

- ↑ The Last Flight from Tallinn Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. at American Foreign Service Association

- ↑ "Five Years of Dates" at Time magazine on Monday, 24 June 1940

- ↑ The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by David J. Smith p.19 ISBN 0-415-28580-1

- ↑ Estonia: Identity and Independence by Jean-Jacques Subrenat, David Cousins, Alexander Harding, Richard C. Waterhouse ISBN 90-420-0890-3

- ↑ (Estonian)51 years from the Raua Street Battle at Estonian Defence Forces Home Page

- ↑ Justice in The Baltic at Time magazine on Monday, 19 August 1940

- ↑ Magnus Ilmjärv Hääletu alistumine, (Silent Submission), Tallinn, Argo, 2004, ISBN 9949-415-04-7

- ↑ U.S.-Baltic Relations: Celebrating 85 Years of Friendship Archived 6 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. at U.S Department of State

- ↑ General Johan Laidoner at The Estonian War Museum

- ↑ fate of individuals arrested at EIHC

- ↑ Individuals executed at EIHC

- ↑ Laar, Mart. War in the Woods: Estonia's Struggle for Survival, 1944–1956. ISBN 0-929590-08-2

- ↑ Biographical Research in Eastern Europe: Altered Lives and Broken Biographies. Humphrey, Miller, Zdravomyslova ISBN 0-7546-1657-6

- ↑ Daniel Fried, Assistant Secretary of State Archived 6 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. at U.S Department of State

- ↑ The Baltic States and their Region: New Europe or Old? by David J. Smith on Page 48 ISBN 90-420-1666-3

- ↑ Post-Cold War Identity Politics: Northern and Baltic Experiences by Marko Lehti on Page 272: Soviet occupation in Baltic countries — a position supported by the fact that an overwhelming majority of states never recognized the 1940 incorporation de jure. ISBN 0-7146-8351-5

- ↑ Diplomats Without a Country: Baltic Diplomacy, International Law, and the Cold War by James T. McHugh , James S. Pacy, Page 2. ISBN 0-313-31878-6

- ↑ The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union: 1917–1991 (Sources in History) Richard Sakwa Page 248, ISBN 0-415-12290-2

- ↑ Heinrich Mark at president.ee

- ↑ Baltic Military District globalsecurity.org

- ↑ Kristina Kallas, Eesti Vabariigi ja Vene Föderatsiooni riikidevahelised läbirääkimised aastatel 1990–1994 – Tartu 2000

- ↑ Eesti Ekspress: Ta astus sajandist pikema sammu – Boriss Jeltsin 1931–2007, 25 April 2007

- ↑ Country Profile: Russia Archived 11 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Foreign & Commonwealth Office of the United Kingdom

- ↑ Citizenship Act of Estonia (§ 5. Acquisition of Estonian citizenship by birth):

- ↑ Text available online. Retrieved 22 July 2010

- ↑ The Forty-Third Session of the UN Sub-Commission at Google Scholar

- ↑ Estonia says Soviet occupation justifies it staying away from Moscow celebrations – Pravda.Ru

- ↑ European Court of Human Rights cases on Occupation of Baltic States

- ↑ Motion for a resolution on the Situation in Estonia by EU

- ↑ U.S.-Baltic Relations: Celebrating 85 Years of Friendship Archived 6 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. at state.gov

- ↑ Russia denies Baltic 'occupation' by BBC News

- ↑ Bush denounces Soviet domination by BBC News

- ↑ Russia denies at newsfromrussia

- ↑ the term "occupation" inapplicable Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. at newsfromrussia

- ↑ Tannberg. Tarvel. Documents on the Soviet Military Occupation of Estonia, Trames, 2006.

- ↑ Maltjuxov, Mixail. The missed opportunity of Stalin. The Soviet Union and the fight for Europe: 1939–1941 (documents, facts, judgements). 2002, Moscow.

- 1 2 Ambrosio, Thomas (2010). "Russia". In Beacháin, Donnacha. The colour revolutions in the former Soviet republics: successes and failures. Abel Polese. Taylor & Francis. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-415-58060-1.

- ↑ Background Note: Estonia AT U.S Department of State

- ↑ "Citizenship Act". Estonian Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 25 July 2007. (Official translation of the law text)

- ↑ Estonia Today Population by Nationality — http://web-static.vm.ee/static/failid/460/Nationalities.pdf

- ↑ http://www.rg.ru/2006/06/28/ukaz-pereselenie.html Ukase of president of Russian Federation Vladimir Putin calling on Russians from former USSR countries to return to the Homeland

- ↑ Corinne Deloy and Rodolphe Laffranque, translated by Helen Levy (4 March 2007). "General elections in Estonia, 4th march 2007". Fondation Robert Schuman. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ↑ "PPA lehele". Mig.ee. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ DELFI. "DELFI: Moskva nõudis KGB töötajatele tagatisi". Delfi.ee. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Estonia is Encouraging a Resurgence of Nazism in Europe". Voice of Russia. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ↑ "Europe must assess neo-Nazism in Estonia — Kokoshin". Interfax. 13 November 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ↑ "State Duma condemns Estonia's 'glorification' of fascism, wants world to 'adequately' assess it". Interfax. 15 November 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ↑ Adrian Blomfield; Bruce Jones (1 May 2007). "Estonia blames memorial violence on Russia". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ↑ "Interfax-Religion". Interfax-Religion. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Breaking News – JTA, Jewish & Israel News

- 1 2 "Interfax-Religion". Interfax-Religion. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Estonia's Nazi fete assailed – Jewish News of Greater Phoenix". Jewishaz.com. 10 August 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Об участии эстонского легиона СС в военных преступлениях в 1941–1945 гг. и попытках пересмотра в Эстонии приговора Нюрнбергского трибунала (Russian)

- ↑ "The truth about eSStonia at". Economist.com. 16 August 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Tonis Lukas at eubusiness.com Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Estonia removes SS monument". BBC News. 24 July 2002. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Estonia unveils Nazi war monument". BBC News. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ 27 April 2005 By Matthias Kolb (27 April 2005). "Looking for the truth behind Lihula". Baltictimes.com. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Postimees 14 September 2004: Semiootikaprofessor Toropi hinnangul ei ole Lihula sammas natslik

- ↑ SL Õhtuleht 14 September 2004: Ekspert Peeter Torop: Lihula mälestussammas pole natslik by Kadri Paas

- ↑ Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission p.950: The Estonian Waffen-SS units cannot be accused of committing crimes against humanity; ISBN 9949-13-040-9

- ↑ United States Congressional Serial Set. Books.google.com. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- 1 2 C. J. Chivers (23 August 2007). "The New York Times Estonia Accuses Ex-Official of Genocide". Estonia: Nytimes.com. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Statement by Mr. Alexander Zhuravskiy, Member of the Delegation of the Russian Federation" (PDF). OSCE Conference on Anti-Semitism and on Other Forms of Intolerance, Cordoba, 8 and 9 June 2005. 9 June 2005. pp. p. 2. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ↑ "Russia backs foreign language test". Herald Sun. Australia. 5 May 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ Max van der Stoel (23 April 1993). "CSCE Communication No. 124" (PDF). OSCE (named CSCE before 1995). pp. p. 3. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ↑ European Centre for Minority Issues: Russian-speaking minorities in Estonia and Latvia: problems of integration at the threshold of the European Union by Peter van Elsuwege]

- ↑ "UNDP: Home page". Developmentandtransition.net. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "UNDP: Home page". Developmentandtransition.net. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 25 February 2004". State.gov. 25 February 2004. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Brown, Kara (1997). "The Russian-Speaking Minority and Estonian Society". KHRONIKA / The Chronicle of Education in Russia and Eurasia, Volume 6, Number 2, Fall 1997. Indiana University. Archived from the original on 13 July 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ "Russian Plan for Invasion of the Baltic States," The Baltic Independent 27 October – 2 November 1995, 2.

- ↑ "Vene poliitikud: nüüd on põhjus sõda alustada" (in Estonian). 27 April 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ↑ The Baltic Times, Parts follows Mari protests with pledge of support

- ↑ "Estonian Institute for Human Rights calling to support Mari People". Suri.ee. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Violations of human rights and democracy in the Republic of Mari El in the Russian Federation". Centre for Geopolitical Studies. 12 May 2005. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- ↑ Religioscope – JFM Recherches et Analyses Sarl. "Religioscope – Two branches of Orthodox Church in Estonia". Religioscope.com. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Правительство предложило Путину отказаться от пограничного договора с Эстонией". Lenta.ru. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Postimees

- ↑ Relations with Russia – Country Studies

- ↑ "Aivars Stranga. The Relations Between Russia And The Baltic States" (PDF). Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Laura Kauppila. The Baltic Puzzle. Russia's Policy towards Estonia and Latvia 1992–1997". Ethesis.helsinki.fi. 27 January 2000. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Россия категорически не приемлет варварское отношение эстонских властей к памяти тех, кто спас Европу от фашизма – заявление сенаторов Interfax, 27 April 2007. Retrieved: 27 April 2007

- ↑ Russia should respond to Estonia by building ports on Baltic coast Interfax, 26 April 2007. Retrieved: 28 April 2007

- ↑ Putin criticizes attempts to belittle World War II heroes Interfax 9 May 2007

- ↑ "Russian MFA Information and Press Department Commentary Regarding a Question from RIA Novosti Concerning the Incident with Estonian Ambassador to Moscow Marina Kaljurand at the office of the newspaper Argumenty i Fakty" (Press release). Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Russia). 4 May 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ↑ "Estonia Makes European Alliance against Russia". Kommersant.com. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ DELFI. "Statement by the Foreign Minister Urmas Paet". Epl.ee. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Wagstyl, Stefan; Parker, George (3 May 2007). "Russia rail move to hit Estonian supply line". The Financial Times. London and Brussels. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ↑ Levitin Says Oil Products Will Avoid Estonia Route

- ↑ The Guardian 17 May 2007: Russia accused of unleashing cyberwar to disable Estonia by Ian Traynor

- ↑ Russia: Ukrainian Insurgent Army members were war criminals, not freedom fighters, Kyiv Post (8 October 2009)

- 1 2 "Russia, Estonia demonstrate mutual dislike at Russia-EU summit". Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Vedomosti. Moscow: RIA Novosti. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 Farizova, Suzanna; Shegedin, Alexander; Strokan, Sergey (30 June 2008). "Estonians Withdrew from Finno-Ugrics". Kommersant. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ↑ "Estonian leader denies seeking Russia's breakup, says Moscow won't accept past". Associated Press. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ↑ "Officials: Estonian Counterintelligence Officer Abducted to Russia at Gunpoint From Estonian Soil". ERR. 5 September 2014.

- ↑ Kangsepp, Liis; Rossi, Juhana (September 5, 2014). "Estonia Says Officer Abducted Near Russian Border". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "Estonia angry at Russia 'abduction' on border". BBC News. 5 September 2014.

- ↑ "Eston Kohver vahetati Aleksei Dresseni vastu välja" (in Estonian). Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ "Kohver released and back in Estonia". Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ А. Голов. Дружественные и недружественные страны для россиян. 30 May 2007.

See also Конфликт с Эстонией:осмысление. 21 May 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Estonia–Russia relations. |

- (Russian) Documents on the Estonia–Russia relationship from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- (Estonian) (Russian) Embassy of Russia in Tallinn

- (English) (Estonian) (Russian) Embassy of Estonia in Moscow

Further reading

- 31 August 2004, the 10th Anniversary of the Withdrawal of Russian Troops from Estonia. Estonia Today, Fact Sheet of the Estonian Foreign Ministry. August 2004.

- Aalto, Pami (2003). Revisiting the Security/Identity Puzzle in Russo-Estonian Relations. Journal of Peace Research 40.5, 573–591.

- Ehin, Piret & Andres Kasekamp (2005). Estonian-Russian Relations in the Context of EU Enlargement. In Kathryn Pinnick & Oksana Antoneko, eds., Russia and the European Union. Volume 1, Part 3, pages 211–224.

- Feldmann, Magnus & Razeen Sally (2002) . From the Soviet Union to the European Union: Estonian Trade Policy, 1991–2000. The World Economy 25 (1), 79–106.

- Kauppila, Laura Eleonoora. The Baltic Puzzle: Russia’s Policy towards Estonia and Latvia, 1992 – 1997. Pro Gradu Thesis, University of Helsinki, 1999.

- Kramer, Mark (2002). NATO, the Baltic states and Russia:a framework for sustainable enlargement. International Affairs 78 (4), 731–756.

- Park, Andrus (1995). Russia and Estonian Security Dilemmas. Europe-Asia Studies 47.1, 27–45.

- Rutenberg, Gregory (1935). The Baltic States and the Soviet Union. The American Journal of International Law 29.4, 598–615.

- Vakar, Nicholai P. (1943). Russia and the Baltic States. Russian Review 3.1, 45–54.

- Vares, Peeter and Olga Zhurayi (1998). Estonia and Russia, Estonians and Russians: A Dialogue. 2nd ed. Tallinn: Olof Palme International Center.

- Vitkus, Gediminas. Changing Security Regime in the Baltic Sea Region. Final report. Vilnius, 2002.

- THE BALTIC PUZZLE – Russia’s Policy towards Estonia and Latvia 1992 – 1997

- Heed a Russian 'Cry of Despair' in Estonia – Andrei Kozyrev in the International Herald Tribune

- Letter dated 9 April 1996 from the Permanent Representative of Estonia to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General