Russia–United Kingdom relations

|

|

United Kingdom |

Russia |

|---|---|

The Russia–United Kingdom relations (Russian: Российско-британские отношения) is the relationship between the Russian Federation and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Spanning nearly five centuries, it has often switched from a state of alliance to rivalry or even war.[1] The Russians and British were allies against Napoleon, and enemies in the Crimean War of the 1850s, and rivals in the Great Game for control of central Asia in the late 19th century. They were allies again in World Wars I and II, although relations were strained by the Russian Revolution of 1917. They were at sword's point during the Cold War (1947–91). Russian big businesses had strong connections with the City of London and British corporations during the late 1990s and 2000s.

However, in 2014 relations turned hostile. The British government took the lead, with France and Germany, in imposing punitive sanctions by the EU against Russia for what Prime Minister David Cameron denounced as Russia's seizure of Crimea and support for separatists in Ukraine. Further sanctions followed after the destruction of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 over rebel territory. Russia warned against reopening the Cold War and responded by partially cutting trade with the EU.[2]

Country comparison

| |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 146267288 | 63134171 |

| Area | 17075400 km2 (6592800 sq mi) | 243910 km2 (94170 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 8/km2 (21/sq mi) | 262/km2 (679/sq mi) |

| Time zones | 9 | 1 |

| Exclusive economic zone | 8095881 km2 (3125837 sq mi) | 6805586 km2 (2627651 sq mi) |

| Capital | Moscow | London |

| Largest City | Moscow (pop. 11503501, 15500100 Metro) | London (pop. 8174100, 14209000 Metro) |

| Government | Federal semi-presidential constitutional republic |

Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Official language | Russian (de facto and de jure) | English (de facto) |

| Main religions | 41% Russian Orthodox, 13% non-religious, 6.5% Islam, 4.1% unaffiliated Christian, 1.5% other Orthodox, 3.4% other religions (2012 Census) | 59.5% Christianity, 25.7% non-religious, 7.2% unstated, 4.4% Islam, 1.3% Hinduism, 0.7% Sikhism, 0.4% Judaism, 0.4% Buddhism (2011 Census) |

| Ethnic groups | 80.90% Russians, 3.96% other Indo-Europeans, 8.75% Turkic peoples, 3.78% Caucasians, 1.76% Finno-Ugric peoples and others | 85.67% white British, 5.27% white (other),1.8% Indian, 1.6% Pakistani, 1.2% white Irish, 1.2% mixed-race, 1.0% black Caribbean, 0.8% black African, 0.5% Bangladeshi, 0.4% other Asian, 0.4% Chinese, 0.6% other |

| GDP (PPP) by the WB | $3.373 trillion | $2.933 trillion |

| GDP (nominal) by the WB | $1.485 trillion | $3.029 trillion |

| Military expenditures | $90.7 billion | $72.7 billion |

| Nuclear warheads active/total | 1,800 / 8,500 | 260 / 290 |

Relations 1553-1792

.jpg)

The Kingdom of England and Tsardom of Russia established relations in 1553 when English navigator Richard Chancellor arrived in Arkhangelsk – at which time Mary I ruled England and Ivan the Terrible ruled Russia. He returned to England and was sent back to Russia in 1555, the same year the Muscovy Company was established. The Muscovy Company held a monopoly over trade between England and Russia until 1698.

In 1697–1698 during the Grand Embassy of Peter I the Russian tsar visited England for three months. He improved relations and learned the best new technology especially regarding ships and navigation.[3]

The Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1800) and later the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1800–1922) had increasingly important ties with the Russian Empire (1721–1917), after Tsar Peter I brought Russia into European affairs and declared himself an emperor. From the 1720s Peter invited British engineers to Saint Petersburg, leading to the establishment of a small but commercially influential Anglo-Russian expatriate merchant community from 1730 to 1921. During the series of general European wars of the 18th century, the two empires found themselves as sometime allies and sometime enemies. The two states fought on the same side during War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48), but on opposite sides during Seven Years' War (1756–63), although did not at any time engage in the field.

Ochakov issue

Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger was alarmed at Russian expansion in Crimea in the 1780s at the expense of his Ottoman ally.[4] He tried to get Parliamentary support for reversing it. In peace talks with the Ottomans, Russia refused to return the key Ochakov fortress. Pitt wanted to threaten military retaliation. However Russia's ambassador Semyon Vorontsov organized Pitt's enemies and launched a public opinion campaign. Pitt won the vote so narrowly that he gave up and Vorontsov secured a renewal of the commercial treaty between Britain and Russia.[5][6]

Relations: 1792-1917

The outbreak of the French Revolution and its attendant wars temporarily united constitutionalist Britain and autocratic Russia in an ideological alliance against French republicanism. Britain and Russia attempted to halt the French but the failure of their joint invasion of the Netherlands in 1799 precipitated a change in attitudes.

Britain occupied Malta, while the Emperor Paul I of Russia was Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller. That led to the never-executed Indian March of Paul, which was a secret project of a planned allied Russo-French expedition against the British possessions in India.

The two countries fought each other (albeit only with some very limited naval combat) during the Anglo-Russian War (1807–12), after which Britain and Russia became allies against Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars. They both played major cooperative roles at the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815.

Russophobia

From 1820 to 1907, a new element emerged: Russophobia. British elite sentiment turned increasingly hostile to Russia, with a high degree of anxiety for the safety of India, With the fear that Russia would push south through Afghanistan. In addition, there was a growing concern that Russia would destabilize Eastern Europe by its attacks on the faltering Ottoman Empire. This fear was known as the Eastern Question.[7] Russia was especially interested in getting a warm water port that would enable its navy. Getting access out of the Black Sea into the Mediterranean was a goal, which meant access through the Straits controlled by the Ottomans.

Both intervened in the Greek War of Independence (1821–29), eventually forcing the London peace treaty on the belligerents. The events heightened Russophobia. In 1851 the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations held in London's Crystal Palace, including over 100,000 exhibits from forty nations. It was the world's first international exposition. Russia took the opportunity to dispel growing Russophobia by refuting stereotypes of Russia as a backward, militaristic repressive tyranny. Its sumptuous exhibits of luxury products and large 'objets d'art' with little in the way of advanced technology, however, did little to change its reputation. Britain considered its navy too weak to worry about, but saw its large army as a major threat.[8]

The Russian pressures on the Ottoman Empire continued, leaving Britain and France to ally with the Ottomans and push back against Russia in the Crimean War (1853–1856). Russophobia was an element in generating popular British support for the far-off war.[9] Elite opinion in Britain, especially among Liberals, supported Poles against harsh Russian rule, after 1830. The British government watched nervously as Russia suppressed revolts in the 1860s but refused to intervene.[10]

At midcentury British observers and travellers presented a highly negative view of Russia as a barbaric and backward nation. The English media depicted the Russians as superstitious, passive, and deserving of their autocratic tsar. Thus "barbarism" stood in contrast to "civilized" Britain.[11] In 1874, tension lessened as Queen Victoria's second son married the only daughter of tsar Alexander II, followed by a cordial state visit by the tsar. The goodwill lasted no more than three years, when structural forces again pushed the two nations to the verge of war.[12]

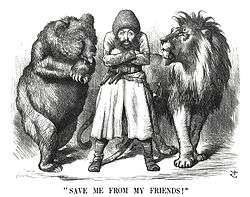

Rivalry between Britain and Russia grew steadily over Central Asia in the Great Game of the late 19th century.[13] Russia desired warm-water ports on the Indian Ocean while Britain wanted to prevent Russian troops from gaining a potential invasion route to India.[14] In 1885 Russia annexed part of Afghanistan in the Panjdeh incident, which caused a war scare. However Russia's foreign minister Nikolay Girs and its ambassador to London Baron de Staal set up an agreement in 1887 which established a buffer zone in Central Asia. Russian diplomacy thereby won grudging British acceptance of its expansionism.[15] Persia was also an arena of tension, but without warfare.[16]

There was cooperation in Asia, however, as the two countries joined many others to protect their interests in China during the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901).[17]

Britain was an ally of Japan after 1902, but remained strictly neutral and did not participate in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5.[18][19][20]

However there was a brief war scare in the Dogger Bank incident in October 1905 when the main Russian battle fleet, headed to fight Japan, mistakenly engaged a number of British fishing vessels in the North Sea fog. The Russians thought they were Japanese torpedo boats, and sank one, killing three fishermen. The British public was angry but Russia apologized and damages were levied through arbitration.[21]

Allies, 1907-1917

Diplomacy became delicate in the early 20th century. Russia was troubled by the Entente Cordiale between Great Britain and France signed in 1904. Russia and France already had a mutual defense agreement that said France was obliged to threaten England with an attack if Britain declared war on Russia, while Russia was to concentrate more than 300,000 troops on the Afghan border for an incursion into India in the event that England attacked France. The solution was to bring Russia into the British-French alliance. The Anglo-Russian Entente and the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 made both countries part of the Triple Entente. Both countries were then part of the subsequent alliance against the Central Powers in the First World War. In the summer of 1914, Austria threatened Serbia, Russia promised to help Serbia, Germany promised to help Austria, and war broke out between Russia and Germany. France supported Russia. Britain was neutral until Germany suddenly invaded neutral Belgium, then Britain joined France and Russia in World War I against Germany and Austria.[22]

United Kingdom – Soviet Union relations

United Kingdom |

Soviet Union |

|---|

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Britain sent troops to Russian ports in the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War, which was designed to limit Soviet aid to the German war effort.

Following the withdrawal of British troops from Russia, negotiations for trade began, and on March 16, 1921, the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement was concluded between the two countries.[23] The United Kingdom recognised the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR or Soviet Union, 1922–1991) on February 1, 1924. Relations between then and the Second World War were tense, typified by the Zinoviev letter incident. Diplomatic relations between the two countries were severed in May 1927 after an Mi5 raid on the All Russian Co-operative Society, but restored in 1929.[24]

Second World War

In 1938, Britain and France negotiated the Munich Agreement with Nazi Germany. The USSR opposed to the pact and refused to recognise the German annexation of the Czechoslovak Sudetenland.

The Soviets felt excluded from Western consideration and vulnerable to possible hostilities by the West or Germany, and in response the USSR signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which promised the Soviets control of about half of Eastern Europe, with Nazi Germany getting the other half. The pact protected Germany and facilitated its invasion of Poland and the Second World War a few days later. Britain declared war on Germany. This complicated relations with Britain as the British leadership was sympathetic to Finland in her war against the USSR (the Winter War), yet could not afford to alienate the Soviets while an attack from Germany was imminent. The USSR however supplied fuel oil to the Germans which was used for Hitler's Luftwaffe in the Blitz against the United Kingdom. Because of the Soviet non-aggression pact with Germany, Hitler's troops were able to overrun most of Western Europe in the summer of 1940.

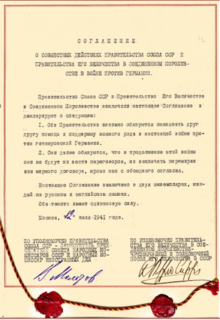

In 1941, Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, attacking the USSR. The USSR thereafter became one of the Allies of World War II along with Britain, fighting against the Axis Powers. The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran secured the oil fields in Iran from falling into Axis hands. The Arctic convoys transported supplies between Britain and the USSR during the war.

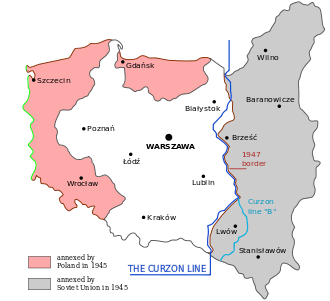

Britain signed a treaty with the USSR and sent military supplies. Stalin was adamant about British support for new boundaries for Poland, and Britain went along. They agreed that after victory Poland's boundaries would be moved westward, so that the USSR took over lands in the east while Poland gained lands in the west that had been under German control.

They agreed on the "Curzon Line" as the boundary between Poland and the Soviet Union) and the Oder-Neisse line would become the new boundary between Germany and Poland. The proposed changes angered the Polish government in exile in London, which did not want to lose control over its minorities. Churchill was convinced that the only way to alleviate tensions between the two populations was the transfer of people, to match the national borders. As he told Parliament on 15 December 1944, "Expulsion is the method which... will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble.... A clean sweep will be made."[25]

In October, 1944, Churchill and Foreign Minister Anthony Eden met in Moscow with Stalin and his foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov. They discussed who would control what in the rest of postwar Eastern Europe. The Americans were not present, were not given shares, and were not fully informed. After lengthy bargaining the two sides settled on a long-term plan for the division of the region, The plan was to give 90% of the influence in Greece to Britain and 90% in Romania to Russia. Russia gained an 80%/20% division in Bulgaria and Hungary. There was a 50/50 division in Yugoslavia, and no Russian share in Italy.[26][27]

Cold War

Following the end of the Second World War, relations between the Soviet and the Western bloc deteriorated quickly. Former British Prime Minister Churchill claimed that the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe after World War II amounted to 'an iron curtain has descended across the continent.' Relations were generally tense during the ensuing Cold War, typified by spying and other covert activities. The British and American Venona Project was established in 1942 for cryptanalysis of messages sent by Soviet intelligence. Soviet spies were later discovered in Britain, such as Kim Philby and the Cambridge Five spy ring, which was operating in England until 1963.

The Soviet spy agency, the KGB, was suspected of the murder of Georgi Markov in London in 1978. A High ranking KGB official, Oleg Gordievsky, defected to London in 1985.

British prime minister Margaret Thatcher pursued a strong anti-communist policy in concert with Ronald Reagan during the 1980s, in contrast with the détente policy of the 1970s, although relations became warmer after Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985.

21st century

After the collapse of the USSR, relations between Britain and the Russian Federation were initially warm. In the 21st century, however, while trade and human ties have proliferated, diplomatic ties have suffered due to allegations of spying, and extradition disputes; thus escalating political tensions between London and Moscow.

The Foundations of Geopolitics, a Russian textbook published in 1997, has been one of the most influential books among Russian military, police, and statist foreign policy elites.[28] The book argues that Russia must isolate the United Kingdom from the politics of continental Europe.[28]

In 2003, Russia requested the extradition of "tycoon" Boris Berezovsky and Chechen separatist Akhmed Zakayev, but Britain refused, having given them both political asylum.[29]

In early 2006, Russia accused UK diplomats of espionage. Along with accusing British diplomats of spying in Moscow with the help of hi-tech electronic rock which were later admitted by Tony Blair's former aide Jonathan Powell that UK was behind plot to spy on Russians with device hidden in fake plastic rock,[30] Russia alleged that British secret service agents had, been funding Russian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) – everything from human rights organisations, to political foundations, or civil liberty groups.[31]

In late 2006, former KGB officer Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned in London by radioactive metalloid, Polonium-210 and died three weeks later. Britain requested the extradition of Andrei Lugovoy from Russia to face charges over Litvinenko's death, Russia refused, stating their constitution does not allow extradition of their citizens to foreign countries. Britain then expelled four Russian diplomats, shortly followed by Russia expelling four British diplomats,[32] the dispute then continued to escalate over the following months. As of 19 May 2008 the head of Counter-Terrorism at the British Crown Prosecution Service, Sue Hemming, said: "The extradition request is still current.[33]

In July 2007, The Crown Prosecution Service announced that Boris Berezovsky would not face charges in the UK for talking to The Guardian about plotting a "revolution" in his homeland. Kremlin officials called it a "disturbing moment" in Anglo-Russian relations. Berezovsky was a wanted man in Russia right up to his death on March 23, 2013, having been accused of embezzlement and money laundering.[34]

In a reminder of the Cold War, Russia recommenced its long range air patrols of the Tupolev Tu-95 bomber aircraft in August 2007. These patrols have neared British airspace, requiring Royal Air Force fighter jets to "scramble" and intercept them.[35][36]

In November 2007, a report by the head of security service MI5 Jonathan Evans, it was stated that "since the end of the Cold War we have seen no decrease in the numbers of undeclared Russian intelligence officers in the UK – at the Russian Embassy and associated organisations – conducting covert activity in this country."[37]

In late 2007, Russia feared that some of its artwork, due to be shown at an exhibition in London, could be seized because of disputes about their ownership. It refused to send the art to the UK until a law was passed by the British government to protect it, initiating fears that the art would not be shown at the exhibition at all. A law was eventually passed and the art was shown.[38]

In January 2008, Russia ordered two offices of the British Council situated in Russia to shut down, accusing them of tax violations. Britain has refuted this claim and the council initially tried to keep their offices open. Work has been suspended at the offices, the council citing "intimidation" by the Russian authorities as the reason. The "Chief Executive" of the council said 20 of their Russian staff had been interviewed by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and a further 10 were visited at their homes by tax police in the night of January 15. On the same night, the son of former British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock, who holds the post of "office director" at the Saint Petersburg branch, was detained for an hour by Russian authorities, allegedly for driving the wrong way up a one-way street and smelling of alcohol.[39][40] However, later in the year a Moscow court threw out most of the tax claims made against the British Council, ruling them invalid.[41]

In 2008, MI5 warned that Russia is a country which is under suspicion of committing murder on British streets.[42]

During the 2008 South Ossetia war between Russia and Georgia, the British Foreign Secretary, David Miliband, visited the Georgian capital city of Tbilisi to meet with the president and said the UK's government and people "stood in solidarity" with the Georgian people.[43]

In November 2009, Miliband visited Russia and he described the state of the current relationship as "respectful disagreement".[44]

Earlier in 2009, then Solicitor-General, Vera Baird, personally decided that the property of the Russian Orthodox Church in the United Kingdom, which had been the subject of a legal dispute following the decision of the administering Bishop and half its clergy and lay adherents to move to the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, would have to remain with the Moscow Patriarchate. She was forced to reassure concerned Members of Parliament that her decision had been made only on legal grounds, and that diplomatic and foreign policy questions had played no part. Baird's determination of the case was however endorsed by the Attorney-General Baroness Patricia Scotland. It attracted much criticism.[45][46] However, questions continue to be raised that Baird's decision was designed not to offend the Putin government in Russia.[47]

In 2010 MI5 warned that Russian spy operations in the United Kingdom are at Cold War levels.[48]

Since 2010

According to David Clark, chair of the independent Russia Foundation, Britain's relations with Russia had undergone a "mini-reset" under the Conservative government of David Cameron, involving tacit agreement to draw a line under the Litvinenko affair, greater emphasis on business and commercial ties, and co-operation on matters of shared interest.

In 2014 relations turned sharply hostile regarding the Ukraine. The British government took the lead, with the US, in imposing punitive sanctions against Russia for what Prime Minister Cameron denounced as Russia's seizure of Crimea and support for insurgents in Ukraine, especially in the wake of shooting down a civilian airliner with (according to American and German intelligence sources) a BUK surface-to-air missile.[2]

In March 2014, Britain suspended all military cooperation with Russia and halted all extant licences for direct military export to Russia.[49] In September, 2014, there were more rounds of sanctions imposed by the EU, targeted at Russian banking and oil industries, and at high officials. Russia responded by cutting off food imports from the UK and other countries imposing sanctions.[50] Cameron said:

- Russia has ripped up the rulebook with its illegal, self-declared annexation of Crimea and its troops on Ukrainian soil threatening and undermining a sovereign nation state.[51]

In May 2014, Putin told journalists:

- I would not like to think this is the start of a new Cold War. It is in no one's interest and I think it will not happen.[52]

On 12 September 2014, in response to the latest round of EU sanctions, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs was highly critical:

- The course of certain forces in the European Union to further aggravate the already strained relations with the Russian Federation becomes obvious.... Now, when there is a fragile peace process going in Ukraine, and the sides began exchanging prisoners, when, as it appeared, all forces should be redirected from presenting mutual accusations and sanctions to finding solutions to the Ukrainian domestic conflict, such steps appear particularly inappropriate and short-sighted.[53]

Upon the ascension of Theresa May as British Prime Minister after the Cameron administration stepped down following defeat in the Brexit referendum, newly appointed Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson stated that he wished to normalise relations between the United Kingdom and the Russian Federation. Moscow said the call between Mr Johnson and his Russian counterpart was initiated by the British government, and that both countries welcomed the prospect of normalised relations.[54]

Russian espionage and influence operations

- The British newspaper The Guardian noted that Russia uses a shadowy army of Russian nationalists to influence opinions on western newspaper websites, including the Guardian's site. Anyone who dares to criticise Russia's leaders, or point out some of the country's deficiencies, is "immediately branded a CIA spy or worse".[55]

- Budget figures showed that Russia was going spend $1.4 billion on international propaganda in 2010, more than on things such as fighting unemployment. Russia purchased a major Russia Today advertising campaign in the United Kingdom.[55]

- The Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers remained affiliated to the International Association of Democratic Lawyers during a period in which it was an international front organization of Soviet intelligence services.[56]

- Andrei Borodin, a Russian banking tycoon who owns Britain’s most expensive house, has been given asylum in The United Kingdom – prompting fury in Moscow.[57]

See also

- Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

- Foreign policy of the Russian Empire to 1917

- Foreign policy of Vladimir Putin

- History of Russia

- International relations (1814–1919)

- List of Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Russia

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

References

- ↑ Edward Ingram, "Great Britain and Russia" in William Thompson, ed., Great Power Rivalries (1999) pp 269-305.

- 1 2 Nicholas Winning, "Cameron Says EU Should Consider New Sanctions Against Russia: U.K. Prime Minister Wants 'Hard-Hitting' Measures After Downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17," Wall Street Journal July 21, 2014

- ↑ Jacob Abbott (1869). History of Peter the Great, Emperor of Russia. Harper. pp. 141–51.

- ↑ John Holland Rose, William Pitt and national revival (1911) pp 589-607.

- ↑ Jeremy Black (1994). British Foreign Policy in an Age of Revolutions, 1783-1793. Cambridge UP. p. 290.

- ↑ John Ehrman, The Younger Pitt: The Reluctant Transition (1996) [vol 2] pp xx.

- ↑ John Howes Gleason, The Genesis of Russophobia in Great Britain: A Study of the Interaction of Policy and Opinion (1950) online

- ↑ Anthony Swift, "Russia and the Great Exhibition of 1851: Representations, perceptions, and a missed opportunity." Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas (2007): 242-263, in English.

- ↑ Andrew D. Lambert, The Crimean War: British Grand Strategy Against Russia, 1853-56 (2011).

- ↑ L. R. Lewitter, "The Polish Cause as seen in Great Britain, 1830–1863." Oxford Slavonic Papers (1995): 35-61.

- ↑ Iwona Sakowicz, "Russia and the Russians opinions of the British press during the reign of Alexander II (dailies and weeklies)." Journal of European studies 35.3 (2005): 271-282.

- ↑ Sir Sidney Lee (1903). Queen Victoria. p. 421.

- ↑ Rodric Braithwaite, "The Russians in Afghanistan." Asian Affairs 42.2 (2011): 213-229.

- ↑ David Fromkin, "The Great Game in Asia," Foreign Affairs(1980) 58#4 pp. 936-951 in JSTOR

- ↑ Raymond Mohl, "Confrontation in Central Asia" History Today 19 (1969) 176-183

- ↑ Firuz Kazemzadeh, Russia and Britain in Persia, 1864-1914: A Study in Imperialism (Yale UP, 1968).

- ↑ Alena N. Eskridge-Kosmach, "Russia in the Boxer Rebellion." Journal of Slavic Military Studies 21.1 (2008): 38-52.

- ↑ B. J. C. McKercher, "Diplomatic Equipoise: The Lansdowne Foreign Office the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, and the Global Balance of Power." Canadian Journal of History 24#3 (1989): 299-340. online

- ↑ Keith Neilson, Britain and the last tsar: British policy and Russia, 1894-1917 (Oxford UP, 1995) p 243.

- ↑ Keith Neilson, "'A dangerous game of American Poker': The Russo‐Japanese war and British policy." Journal of Strategic Studies 12#1 (1989): 63-87. online

- ↑ Richard Ned Lebow, "Accidents and Crises: The Dogger Bank Affair." Naval War College Review 31 (1978): 66-75.

- ↑ Neilson, Britain and the last tsar: British policy and Russia, 1894-1917 (1995).

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 4, pp. 128–136.

- ↑ For an account of the break in 1927, see Roger Schinness, "The Conservative Party and Anglo-Soviet Relations, 1925–27", European History Quarterly 7, 4 (1977): 393–407.

- ↑ Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, 1897–1963 (1974) vol 7 p 7069

- ↑ Albert Resis, "The Churchill-Stalin Secret "Percentages" Agreement on the Balkans, Moscow, October 1944," American Historical Review (1978) 83#2 pp. 368–387 in JSTOR

- ↑ Klaus Larres, A companion to Europe since 1945 (2009) p. 9

- 1 2 John B. Dunlop (August 2003). "Aleksandr Dugin's Foundations of Geopolitics" (PDF). Princeton University.

- ↑ "Mood for a fight in UK-Russia row". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ Topping, Alexandra; Elder, Miriam (2012-01-19). "Britain admits 'fake rock' plot to spy on Russians". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "UK diplomats in Moscow spying row". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Russia expels four embassy staff". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Will Lugovoi still stand trial?". BBC News. 2008-05-19. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ↑ Anglo-Russian relations April 7, 2008

- ↑ BBC Media Player

- ↑ "Russia's Bear bomber returns". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ Sky News report with Quote

- ↑ "Russian art show gets green light". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Russia to limit British Council". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Russia actions 'stain reputation'". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "British Council wins Russia fight". BBC News. 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ Russian spies leaving the door open for terrorists in Britain. The Telegraph 2008-07-05

- ↑ "Miliband in Georgia support vow". BBC News. 2008-08-19. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Kendall, Bridget (2009-11-03). "'Respectful disagreement' in Moscow". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ "The Battle for Britain's Orthodox Church". The Independent. 2009-02-11. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ↑ "Who controls Russian Orthodoxy in Britain?". openDemocracy. 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ "BBC Russian Service: farewell to old friends". openDemocracy. 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ Norton-Taylor, Richard (2010-06-29). "Russian spies in UK 'at cold war levels', says MI5". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "UK suspends Military and Defense Ties with Russia over Crimea Annexure". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "Ukraine crisis: Russia and sanctions" BBC News 13 Sept. 2014

- ↑ Adrian Croft and Kylie MacLellan, "NATO shakes up Russia strategy over Ukraine crisis," Reuters, Sept. 4.2014

- ↑ Paul Ingrassia, "Putin says no new Cold War, no way back to the USSR," Reuters, May 24, 2014

- ↑ "Russia feels sorry about failed strategic partner, EU," Pravda Sept 12, 2014

- ↑ "Boris Johnson says Britain must 'normalise' its relationship with Russia, " "The Telegraph" 11 August, 2016

- 1 2 Russia Today launches first UK ad blitz. The Guardian. 18 December 2009.

- ↑ Against the Cold War: The History and Political Traditions of Pro-Sovietism in the British Labour Party, 1945–89 (2004). Darren G. Lilleker. p.91

- ↑ Stewart, Will (2013-03-01). "Kremlin anger as Britain grants political asylum to Russian banker wanted on criminal charges in Moscow". Daily Mail. London.

Further reading

Multilateral diplomacy

- Albrecht-Carrié, René. A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna (1958), 736pp, basic introduction 1815–1955

- Feis, Herbert. Churchill Roosevelt Stalin The War They Waged and the Peace They Sought A Diplomatic History of World War II (1957)

- Figes, Orlando. The Crimean War: A History (2011) excerpt and text search

- McNeill, William Hardy. America, Britain, & Russia: Their Co-Operation and Conflict, 1941–1946 (1953)

- Macmillan, Margaret. The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013) cover 1890s to 1914; see esp. ch 2, 5, 6, 7

- Mckay, Derek and H.M. Scott. The Rise of the Great Powers 1648–1815 (1983)

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914 (1991), comprehensive survey

- Schroeder, Paul W. The transformation of European politics, 1763–1848 (1994) highly detailed analysis

- Taylor, A.J.P. Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 (1954) highly detailed analysis

Bilateral relations

- Anderson, M. S. Britain's Discovery of Russia 1553–1815 (1958). online

- Bartlett, C. J. British Foreign Policy in the Twentieth Century (1989)

- Bell, P. M. H. John Bull and the Bear: British Public Opinion, Foreign Policy and the Soviet Union 1941–45 (1990).

- Carlton, David. Churchill and the Soviet Union (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000).

- Chamberlain, Muriel E. Pax Britannica?: British Foreign Policy 1789–1914 (1989)

- Clarke, Bob. Four Minute Warning: Britain's Cold War (2005)

- Cross, A. G. ed. The Russian Theme in English Literature from the Sixteenth Century to 1980: An Introductory Survey and a Bibliography (1985).

- Deighton Anne. "The 'Frozen Front': The Labour Government, the Division of Germany and the Origins of the Cold War, 1945–1947," International Affairs 65, 1987: 449–465. in JSTOR

- Deighton, Anne. The Impossible Peace: Britain, the Division of Germany and the Origins of the Cold War (1990)

- Fuller, William C. Strategy and Power in Russia 1600–1914 (1998)

- Gleason, John Howes. The Genesis of Russophobia in Great Britain: A Study of the Interaction of Policy and Opinion (1950) online

- Gorodetsky, Gabriel, ed. Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–1991: A Retrospective (2014)

- Haslam, Jonathan. Russia's Cold War: From the October Revolution to the Fall of the Wall (Yale UP, 2011)

- Horn, David Bayne. Great Britain and Europe in the eighteenth century (1967), covers 1603 to 1702; pp 201–36.

- Ingram, Edward. "Great Britain and Russia," pp 269–305 in William R. Thompson, ed. Great power rivalries (1999) online

- Jelavich, Barbara. St. Petersburg and Moscow: Tsarist and Soviet foreign policy, 1814–1974 (1974)

- Jones, J. R. Britain and the World, 1649–1815 (1980)

- Keeble, Curtis. Britain and the Soviet Union, 1917–1989 (London: Macmillan, 1990).

- Kort, Michael. The Soviet Colossus: History and Aftermath (7th ed. 2010) 502pp

- Miner, Steven Merritt. Between Churchill and Stalin: The Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the Origins of the Grand Alliance (1988) online

- Morgan, Gerald, and Geoffrey Wheeler. Anglo-Russian Rivalry in Central Asia, 1810–1895 (1981)

- Neilson, Keith. Britain and the Last Tsar: British Policy and Russia, 1894–1917 (1995) online

- Neilson, Keith Britain, Soviet Russia and the Collapse of the Versailles Order, 1919–1939 (2006)

- Reynolds, David, et al. Allies at War: The Soviet, American, and British Experience, 1939–1945 (1994).

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. and Mark D. Steinberg. A History of Russia. (7th ed. Oxford University Press, 2004) 800 pages.

- Service, Robert. A History of Twentieth-Century Russia. (2nd ed. Harvard UP, 1999)

- Service, Robert. Stalin: A Biography (2004)

- Seton-Watson, Hugh. The Russian Empire 1801–1917 (1967) excerpt and text search

- Shaw, Louise Grace. The British Political Elite and the Soviet Union, 1937–1939 (2003) online

- Williams, Beryl J. "The Strategic Background to the Anglo-Russian Entente of August 1907." Historical Journal 9#3 (1966): 360-373.

- Zubok, Vladislav and Pleshakov, Constantine. Inside the Kremlin's Cold War: From Stalin to Khrushchev (1996).

- Густерин П. В. Советско-британские отношения между мировыми войнами. — Саарбрюккен: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing. 2014. ISBN 978-3-659-55735-4 .

Primary sources

- Watt, D.C. (ed.) British Documents on Foreign Affairs, Part II, Series A: The Soviet Union, 1917–1939 vol. XV (University Publications of America, 1986).

- Wiener, Joel H. ed. Great Britain: Foreign Policy and the Span of Empire, 1689–1971: A Documentary History (4 vol 1972) vol 1 online; vol 2 online; vol 3; vol 4 4 vol. 3400 pages

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of Russia and the United Kingdom. |

- BBC news, timeline of recent Anglo-Russian relations

- The Economist, Anglo-Russian relations, The big freeze

- Bilateral agreements between Russia and the United Kingdom