European Court of Justice

| Court of Justice | |

|---|---|

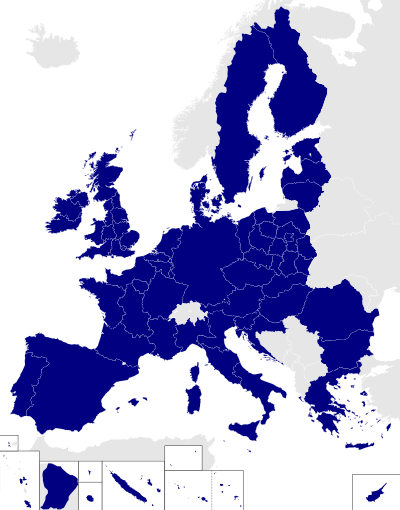

|

Emblem of the Court of Justice of the European Union .svg.png) Jurisdiction of the Court of Justice | |

| Established | 1952 |

| Country | European Union |

| Location | Luxembourg |

| Number of positions | 28 + 11 |

| Website | Curia.europa.eu |

| President | |

| Currently | Koen Lenaerts |

| Since | 8 October 2015 |

| Vice-President | |

| Currently | Antonio Tizzano |

| Since | 8 October 2015 |

| European Union |

This article is part of a series on the |

Policies and issues

|

The European Court of Justice (ECJ), officially just the Court of Justice (French: Cour de Justice), is the highest court in the European Union in matters of European Union law. As a part of the Court of Justice of the European Union it is tasked with interpreting EU law and ensuring its equal application across all EU member states.[1] The Court was established in 1952 and is based in Luxembourg. It is composed of one judge per member state – currently 28 – although it normally hears cases in panels of three, five or 15[2] judges. The court has been led by president Koen Lenaerts since 2015.[1]

History

The court was established in 1952, by the Treaty of Paris (1951) as part of the European Coal and Steel Community.[1] It was established with seven judges, allowing both representation of each of the six member States and being an unequal number of judges in case of a tie. One judge was appointed from each member state and the seventh seat rotated between the "large Member States" (Germany, France and Italy). It became an institution of two additional Communities in 1957 when the European Economic Community (EEC), and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) were created, sharing the same courts with the European Coal and Steel Community.

The Maastricht Treaty was ratified in 1993, and created the European Union. The name of the Court did not change unlike the other institutions. The power of the Court resided in the Community pillar (the first pillar).[3]

The Court gained power in 1997 with the signing of the Amsterdam Treaty. Issues from the third pillar were transferred to the first pillar. Previously, these issues were settled between the member states.

Following the entrance into force of the Treaty of Lisbon on 1 December 2009, the ECJ's official name was changed from the "Court of Justice of the European Communities" to the "Court of Justice" although in English it is still most common to refer to the Court as the European Court of Justice. The Court of First Instance was renamed as the "General Court", and the term "Court of Justice of the European Union" will officially designate the two courts, as along with its specialised tribunals, taken together.[4]

Overview

.jpg)

The ECJ is the highest court of the European Union in matters of Union law, but not national law. It is not possible to appeal the decisions of national courts to the ECJ, but rather national courts refer questions of EU law to the ECJ. However, it is ultimately for the national court to apply the resulting interpretation to the facts of any given case. Although, only courts of final appeal are bound to refer a question of EU law when one is addressed. The treaties give the ECJ the power for consistent application of EU law across the EU as a whole.

The court also acts as arbiter between the EU's institutions and can annul the latter's legal rights if it acts outside its powers.[1]

The judicial body is now undergoing strong growth, as witnessed by its continually rising caseload and budget. The Luxembourg courts received more than 1,300 cases when the most recent data was recorded in 2008, a record. The staff budget also hit a new high of almost €238 million in 2009,[5] while in 2014 €350 million were budgeted.[6]

Composition

Judges

The Court of Justice consists of 28 Judges who are assisted by 11 (as of 05/10/2016) Advocates-General. The Judges and Advocates-General are appointed by common accord of the governments of the member states[7] and hold office for a renewable term of six years. The treaties require that they are chosen from legal experts whose independence is "beyond doubt" and who possess the qualifications required for appointment to the highest judicial offices in their respective countries or who are of recognised competence.[7] 37% of judges had experience of judging appeals before they joined the ECJ.[8] In practice, each member state nominates a judge whose nomination is then ratified by all the other member states.[9]

President

The President of the Court of Justice is elected from and by the judges for a renewable term of three years. The president presides over hearings and deliberations, directing both judicial business and administration (for example, the time table of the Court and Grand Chamber). He also assigns cases to the chambers for examination and appoints judge as rapporteurs (reporting judges).[10] The Council may also appoint assistant rapporteurs to assist the President in applications for interim measures and to assist rapporteurs in the performance of their duties.[11]

| # | Term | President | State |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1952–1958 | Massimo Pilotti | |

| 2 | 1958–1964 | Andreas Matthias Donner | |

| 3 | 1964–1967 | Charles Léon Hammes | |

| 4 | 1967–1976 | Robert Lecourt | |

| 5 | 1976–1980 | Hans Kutscher | |

| 6 | 1980–1984 | Josse Mertens de Wilmars | |

| 7 | 1984–1988 | John Mackenzie-Stuart | |

| 8 | 1988–1994 | Ole Due | |

| 9 | 1994–2003 | Gil Carlos Rodríguez Iglesias | |

| 10 | 7 October 2003 – 6 October 2015 | Vassilios Skouris | |

| 11 | 8 October 2015–incumbent Term expires 6 October 2018 | Koen Lenaerts | |

| Source: "The Presidents of the Court of Justice". CVCE. Retrieved 19 April 2013. | |||

Vice-President

The post of vice-president was created by amendments to the Statute of the Court of Justice in 2012. The duty of the Vice-President is to assist the President in the performance of his duties and to take the President's place when the latter is prevented from attending or when the office of president is vacant. In 2012, judge Koen Lenaerts of Belgium became the first judge to carry out the duties of the Vice-President of the Court of Justice. Like the President of the Court of Justice, the Vice-President is elected by the members of the Court for a term of three years.[12]

| # | Term | President | State |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 October 2012 – 6 October 2015 | Koen Lenaerts | |

| 2 | 8 October 2015–incumbent Term expires 6 October 2018 | Antonio Tizzano | |

Advocates General

The judges are assisted by eleven[13] Advocates General who are responsible for presenting a legal opinion on the cases assigned to them. They can question the parties involved and then give their opinion on a legal solution to the case before the judges deliberate and deliver their judgment. The intention behind having Advocates General attached is to provide independent and impartial opinions concerning the Court's cases. Unlike the Court's judgments, the written opinions of the Advocates General are the works of a single author and are consequently generally more readable and deal with the legal issues more comprehensively than the Court, which is limited to the particular matters at hand. The opinions of the Advocates General are advisory and do not bind the Court, but they are nonetheless very influential and are followed in the majority of cases.[14] In a 2016 study, Arrebola and Mauricio measured the influence of the Advocate General on the judgments of the Court, showing that the Court is approximately 67% more likely to deliver a particular outcome if that was the opinion of the Advocate General.[15] As of 2003, Advocates General are only required to give an opinion if the Court considers the case raises a new point of law.[1][16]

Six of the eleven[13] Advocates General are nominated as of right by the six largest member states of the European Union: Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain and Poland. The other five positions rotate in alphabetical order between the 23 smaller Member States : currently Belgium, Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Czech Republic.[17] Being only a little smaller than Spain, Poland has repeatedly requested a permanent Advocate General. Under the Lisbon Treaty, the number of Advocates General may—if the Court so requests—be increased to 11, with six being held permanently by the six biggest member states (adding Poland to the above-mentioned five member states), and five being rotated between the other member states.[18]

The Registrar

The Registrar is the Court's chief administrator. They manage departments under the authority of the Court's president.[16] The Court may also appoint one or more Assistant Registrars. They help the Court, the Chambers, the President and the Judges in all their official functions. They are responsible for the Registry as well as for the receipt, transmission and custody of documents and pleadings that have been entered in a register initialled by the President. They are Guardian of the Seals and responsible for the Court's archives and publications. The Registrar is responsible for the administration of the Court, its financial management and its accounts. The operation of the Court is in the hands of officials and other servants who are responsible to the Registrar under the authority of the President. The Court administers its own infrastructure; this includes the Translation Directorate, which, as of 2012 employed 44.7% of the staff of the institution.[19]

Chambers

The Court can sit in plenary session, as a Grand Chamber of fifteen judges (including the president and vice-president), or in chambers of three or five judges. Plenary sittings are now very rare, and the court mostly sits in chambers of three or five judges.[20] Each chamber elects its own president who is elected for a term of three years in the case of the five-judge chambers or one year in the case of three-judge chambers.

The Court is required to sit in full court in exceptional cases provided for in the treaties. The court may also decide to sit in full, if the issues raised are considered to be of exceptional importance.[1] Sitting as a Grand Chamber is more common and can happen when a Member State or a Union institution, that is a party to certain proceedings, so requests, or in particularly complex or important cases.

The court acts as a collegial body: decisions are those of the court rather than of individual judges; no minority opinions are given and indeed the existence of a majority decision rather than unanimity is never suggested.[21]

Jurisdiction and powers

It is the responsibility of the Court of Justice to ensure that the law is observed in the interpretation and application of the Treaties of the European Union and of the provisions laid down by the competent Community institutions[22] To enable it to carry out that task, the Court has broad jurisdiction to hear various types of action. The Court has competence, among other things, to rule on applications for annulment or actions for failure to act brought by a Member State or an institution, actions against Member States for failure to fulfil obligations, references for a preliminary ruling and appeals against decisions of the General Court .[1]

Actions for failure to fulfill obligations: infringement procedure

Under Article 258 (ex Article 226) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the Court of Justice may determine whether a Member State has fulfilled its obligations under Union law. The commencement of proceedings before the Court of Justice is preceded by a preliminary procedure conducted by the Commission, which gives the Member State the opportunity to reply to the complaints against it. If that procedure does not result in termination of the failure by the Member State, an action for breach of Union law may be brought before the Court of Justice. That action may be brought by the Commission – as is practically always the case – or by another Member State, although the cases of the latter kind remain extremely rare.[23] If the Court finds that an obligation has not been fulfilled, the Member State concerned must terminate the breach without delay. If, after new proceedings are initiated by the Commission, the Court of Justice finds that the Member State concerned has not complied with its judgment, it may, upon the request of the Commission, impose on the Member State a fixed or a periodic financial penalty.[24] According to decision from the court show, if the European Commission does not send the formal letter to the violating member state no-one can force them.[25]

Actions for annulment

By an action for annulment under Article 263 (ex Article 230) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the applicant seeks the annulment of a measure (regulation, directive or decision) adopted by an institution. The Court of Justice has exclusive jurisdiction over actions brought by a Member State against the European Parliament and/or against the Council (apart from Council measures in respect of State aid, dumping and implementing powers) or brought by one Community institution against another. The General Court has jurisdiction, at first instance, in all other actions of this type and particularly in actions brought by individuals. The Court of Justice has the power to declare measures void under Article 264 (ex Article 231) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Actions for failure to act

Under Article 265 (ex Article 232) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the Court of Justice and the General Court may also review the legality of a failure to act on the part of a Union institution. However, such an action may be brought only after the institution has been called on to act. Where the failure to act is held to be unlawful, it is for the institution concerned to put an end to the failure by appropriate measures.

Application for compensation based on non-contractual liability

Under Article 268 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (and with reference to Article 340), the Court of Justice hears claims for compensation based on non-contractual liability, and rules on the liability of the Community for damage to citizens and to undertakings caused by its institutions or servants in the performance of their duties.

Appeals on points of law

Under Article 256 (ex Article 225) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, appeals on judgments given by the General Court may be heard by the Court of Justice only if the appeal is on a point of law. If the appeal is admissible and well founded, the Court of Justice sets aside the judgment of the General Court. Where the state of the proceedings so permits, the Court may itself decide the case. Otherwise, the Court must refer the case back to the General Court, which is bound by the decision given on appeal.

References for a preliminary ruling

References for a preliminary ruling are specific to Union law. Whilst the Court of Justice is, by its very nature, the supreme guardian of Union legality, it is not the only judicial body empowered to apply EU law.

That task also falls to national courts, in as much as they retain jurisdiction to review the administrative implementation of Union law, for which the authorities of the Member States are essentially responsible; many provisions of the Treaties and of secondary legislation – regulations, directives and decisions – directly confer individual rights on nationals of Member States, which national courts must uphold.

National courts are thus by their nature the first guarantors of Union law. To ensure the effective and uniform application of Union legislation and to prevent divergent interpretations, national courts may, and sometimes must, turn to the Court of Justice and ask that it clarify a point concerning the interpretation of Union law, in order, for example, to ascertain whether their national legislation complies with that law. Petitions to the Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling are described in Article 267 (ex Article 234) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

A reference for a preliminary ruling may also seek review of the legality of an act of Union law. The Court of Justice's reply is not merely an opinion, but takes the form of a judgment or a reasoned order. The national court to which that is addressed is bound by the interpretation given. The Court's judgment also binds other national courts before which a problem of the same nature is raised.

Although such a reference may be made only by a national court, which alone has the power to decide that it is appropriate do so, all the parties involved – that is to say, the Member States, the parties in the proceedings before national courts and, in particular, the Commission – may take part in proceedings before the Court of Justice. In this way, a number of important principles of Union law have been laid down in preliminary rulings, sometimes in answer to questions referred by national courts of first instance.

In the ECJ's 2009 report it was noted that Belgian, German and Italian judges made the most referrals for an interpretation of EU law to the ECJ. However, the German Constitutional Court has rarely turned to the European Court of Justice, which is why lawyers and law professors warn about a future judicial conflict between the two courts. On February 7, 2014, the German Constitutional Court referred its first and only case to the ECJ for a ruling on a European Central Bank program.[26]

Procedure and working languages

Procedure before the ECJ is determined by its own rules of procedure.[27] As a rule the Court's procedure includes a written phase and an oral phase. The proceedings are conducted in one of the official languages of the European Union chosen by the applicant, although where the defendant is a member state or a national of a member state the applicant must choose an official language of that member state, unless the parties agree otherwise.[28]

However the working language of the court is French and it is in this language that the judges deliberate, pleadings and written legal submissions are translated and in which the judgment is drafted.[29] The Advocates-General, by contrast, may work and draft their opinions in any official language, as they do not take part in any deliberations. These opinions are then translated into French for the benefit of the judges and their deliberations.[30]

Seat

All the EU's judicial bodies are based in Luxembourg, separate from the political institutions in Brussels and Strasbourg. The Court of Justice is based in the Palais building, currently under expansion, in the Kirchberg district of Luxembourg.

Luxembourg was chosen as the provisional seat of the Court on 23 July 1952 with the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community. Its first hearing there was held on 28 November 1954 in a building known as Villa Vauban, the seat until 1959 when it would move to the Côte d'Eich building and then to the Palais building in 1972.[31]

In 1965, the member states established Luxembourg as the permanent seat of the Court. Future judicial bodies (Court of First Instance and Civil Service Tribunal) would also be based in the city. The decision was confirmed by the European Council at Edinburgh in 1992. However, there was no reference to future bodies being in Luxembourg. In reaction to this, the Luxembourgian government issued its own declaration stating it did not surrender those provisions agreed upon in 1965. The Edinburgh decision was attached to the Amsterdam Treaty. With the Treaty of Nice Luxembourg attached a declaration stating it did not claim the seat of the Boards of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market – even if it were to become a judicial body.[31]

Landmark decisions

Over time ECJ developed two essential rules on which the legal order rests: direct effect and supremacy. The court first ruled on the direct effect of primary legislation in a case that, though technical and tedious, raised a fundamental principle of Union law. In Van Gend en Loos (1963), a Dutch transport firm brought a complaint against Dutch customs for increasing the duty on a product imported from Germany. The court ruled that the Community constitutes a new legal order, the subjects of which consist of not only the Member States but also their nationals. The principle of direct effect would have had little impact if Union law did not supersede national law. Without supremacy the Member States could simply ignore EU rules. In Costa v ENEL (1964), the court ruled that member states had definitively transferred sovereign rights to the Community and Union law could not be overridden by domestic law.[32]

Another early landmark case was Commission v Luxembourg & Belgium (1964), the "Dairy Products" case.[33] In that decision the Court comprehensively ruled out any use by the Member States of the retaliatory measures commonly permitted by general international law within the European Economic Community. That decision is often thought to be the best example of the European legal order's divergence with ordinary international law.[34] Commission v Luxembourg & Belgium also has a logical connection with the nearly contemporaneous Van Gend en Loos and Costa v ENEL decisions, as arguably it is the doctrines of direct effect and supremacy that allow the European legal system to forego any use of retaliatory enforcement mechanisms by the Member States.[35]

Further, in the 1991 Francovich case, the ECJ established that Member States could be liable to pay compensation to individuals who suffered a loss by reason of the Member State's failure to transpose an EU directive into national law.C-6/90

Criticism

Some MEPs and industry spokesmen have criticised the ruling against the use of gender as factor in determining premiums for insurance products. British Conservative MEP Sajjad Karim remarked, "Once again we have seen how an activist European Court can over-interpret the treaty. The EU's rules on sex discrimination specifically permit discrimination in insurance if there is data to back it up".[36]

The status and jurisdiction of the ECJ has been questioned by representatives of member states' judiciary:

- In Germany, the former president Roman Herzog warned that the ECJ was overstepping its powers, writing that "the ECJ deliberately and systematically ignores fundamental principles of the Western interpretation of law, that its decisions are based on sloppy argumentation, that it ignores the will of the legislator, or even turns it into its opposite, and invents legal principles serving as grounds for later judgments". Herzog is particularly critical in its analysis of the Mangold Judgment, which over-ruled a German law that would discriminate in favour of older workers.[37]

- The President of the Constitutional Court of Belgium, Marc Bossuyt, said that both the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights were taking on more and more powers by extending their competences, creating a serious threat of a "government by judges". He stated that "they fabricate rulings in important cases with severe financial consequences for governments without understanding the national rules because they are composed out of foreign judges".[38]

The ECJ has also been criticised for spending too much money. As examples of overspending the critics refer to the building of the Luxembourg courthouse in 2009 that cost €500 million and the fact that the 28 judges and nine Advocates-General each have a chauffeured car.[6]

See also

- European Court of Human Rights

- European Free Trade Association Court

- List of European Court of Justice rulings

- Relationship between the European Court of Justice and European Court of Human Rights

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Court of Justice". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ↑ http://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/Jo2_7024

- ↑ Muñoz, Susana. "The Court of Justice and the Court of First Instance of the European Communities". CVCE. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ↑ See SCADPlus: The Institutions of the Union and article 2.3n of the Draft Reform Treaty of 23 July 2007

- ↑ "EU High Court Amassing Strength & Reach , Art. 13". Courthouse News Service. 10 September 2009.

- 1 2 telegraph.co.uk: "Justice, the EU and its £415m gilded Tower of Babel" 9 Feb 2014

- 1 2 Article 253 (ex Article 223) of the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union.

- ↑ The European Court of Justice has taken on huge new powers as ‘enforcer’ of last week’s Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance. Yet its record as a judicial institution has been little scrutinised., Professor Damian Chalmers, 7 May 2012, LSE European Politics and Policy blog

- ↑ Simon Hix (2005). The Political System of the European Union (2nd ed.). Palgrave. p. 117.

- ↑ Muñoz, Susana. "Organisation of the Court of Justice and the Court of First Instance of the European Communities". CVCE. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ↑ "Protocol on the Statute of the Court of Justice, Article 13" (PDF). European Union. 28 June 2009.

- ↑ Under Article 9a of the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union: The Judges shall elect the President and the Vice-President of the Court of Justice from among their number for a term of three years.

- 1 2 "Press Release 3251st Council meeting: General Affairs (provisional version)" (pdf) (Press release). Council of the European Union. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

. . . the number of Advocates-General of the Court of Justice will increased to nine, with effect from 1 July 2013, and to eleven, from 7 October 2015 onwards.

- ↑ Craig and de Búrca, page 70.

- ↑ Arrebola, Carlos and Mauricio, Ana Julia and Jiménez Portilla, Héctor, An Econometric Analysis of the Influence of the Advocate General on the Court of Justice of the European Union (January 12, 2016). Cambridge Journal of Comparative and International Law, Vol. 5, No. 1, Forthcoming; University of Cambridge Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 3/2016. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2714259

- 1 2 "The Court of Justice of the European Communities". Court of Justice. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ↑ As determined from its .

- ↑ "Lisbon Treaty". Government of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ↑ "Departments of the Institution: Translation". The European Union, ECJ. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ As can be seen from the decline in cases pending before the full court: Annual Report, 2007 (PDF), The Court of Justice of the European Communities, p. 94

- ↑ Craig and de Búrca, page 95.

- ↑ By the Treaty of Lisbon, this skill also includes respect for human rights, protected by the Charter of Nice has become part of EU law. For a confluence of that jurisdiction to that of the European Court of Human Rights, based in Strasbourg, see (Italian) Giampiero Buonomo, Sanzioni ed elusioni, in Mondoperaio, marzo 2015.

- ↑ see for instance 141/78 France v United Kingdom, C-388/95 Belgium v Spain and C-145/04 Spain v United Kingdom.

- ↑ Repubblica italiana, Senato della Repubblica, Gli oneri finanziari del contenzioso con l'Unione europea

- ↑ Infringement Proceedings: Fail to Act (Article 258 TFUE) -> Complaints (Article 265 LT) - Overview of Requests.

- ↑ "Europe or Democracy? What German Court Ruling Means for the Euro". Spiegel Online International. Spiegel Online International.

- ↑ "Rules of Procedure of the European Court of Justice" (PDF). 2 July 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ Article 29(2) of the Rules of Procedure.

- ↑ Sharpston, Eleanor V. E. (29 March 2011), "Appendix 5: Written Evidence of Advocate General Sharpston", The Workload of the Court of Justice of the European Union, House of Lords European Union Committee, retrieved 27 August 2013

- ↑ On the Linguistic Design of Multinational Courts—The French Capture, forthcoming in 14 INT’L J. CONST. L. (2016), MATHILDE COHEN

- 1 2 Muñoz, Susana. "Seat of the Court of Justice and the Court of First Instance of the European Communities.". CVCE. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ↑ Desmond Dinan, Ever Closer Union: An Introduction to European Integration, p292-293.

- ↑ ECJ Cases 90&91/63, Commission v Luxembourg & Belgium, [1964] ECR 625

- ↑ JHH Weiler, 'The Transformation of Europe' (1991) 100 Yale Law Journal 2403-2483 2422 and ft 42

- ↑ W Phelan, 'The Troika: The Interlocking Roles of Commission v Luxembourg and Belgium, Van Gend en Loos and Costa v ENEL in the Creation of the European Legal Order' (2015) 21 (1) European Law Journal 116-135, Phelan, William (2016). 'Supremacy, Direct Effect, and Dairy Products in the Early History of European law.' International Journal of Constitutional Law 14: 6-25.

- ↑ ECJ insurance ruling condemned by MEPs – The Parliament

- ↑ Stop the European Court of Justice – Roman Herzog and Lüder Gerken. OpEd article in the EUobserver.

- ↑ "Bossuyt waarschuwt voor 'regering door rechters'". Hbvl.be. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

Further reading

- Gunnar Beck, The Legal Reasoning of the Court of Justice of the EU, Hart Publishing (Oxford), 2013.

- Gerard Conway, The Limits of Legal Reasoning and the European Court of Justice, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge), 2012

- Craig, Paul; de Búrca, Gráinne (2011). EU Law, Text, Cases and Materials (5th ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-957699-8.

- Alec Stone Sweet, The Judicial Construction of Europe (Oxford University Press, 2004)

- Alec Stone Sweet, "The European Court of Justice and the Judicialisation of EU Governance," Living Reviews in European Governance 5 (2010) 2, http://www.livingreviews.org/lreg-2010-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to European Court of Justice. |

- Official website

- CourtofJustice.EU – blog with case law of the European Court of Justice

- European Court of Justice – Centre Virtuel de la connaissance sur l'Europe – CVCE

- Hochtief: European Court of Justice, about the buildings

- Josselin, J. M.; Marciano, A. (2006). "How the court made a federation of the EU". The Review of International Organizations. 2: 59. doi:10.1007/s11558-006-9001-y.

Coordinates: 49°37′16″N 6°08′26″E / 49.621050°N 6.140616°E