2003 European heat wave

| 2003 European heat wave | |

|---|---|

| Dates | July to August 2003 |

| Areas affected | Mostly

Western Europe |

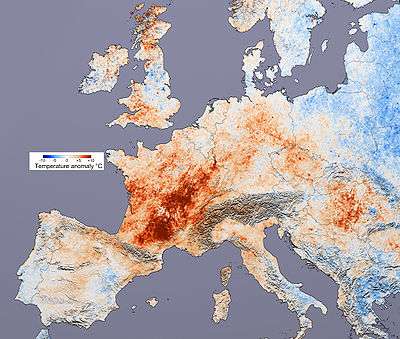

The 2003 European heat wave led to the hottest summer on record in Europe since at least 1540.[1] France was hit especially hard. The heat wave led to health crises in several countries and combined with drought to create a crop shortfall in parts of Southern Europe. Peer-reviewed analysis places the European death toll at more than 70,000.[2] The predominant heat was recorded in July and August, partly a result of the western European seasonal lag from the maritime influence of the Atlantic warm waters in combination with hot continental air and strong southerly winds.

By country

France

In France, 14,802 heat-related deaths (mostly among the elderly) occurred during the heat wave, according to the French National Institute of Health.[4][5] France does not commonly have very hot summers, particularly in the northern areas,[6] but eight consecutive days with temperatures of more than 40 °C (104 °F) were recorded in Auxerre, Yonne in early August 2003. Because of the usually relatively mild summers, most people did not know how to react to very high temperatures (for instance, with respect to rehydration), and most single-family homes and residential facilities built in the last 50 years were not equipped with air conditioning. Furthermore, while contingency plans were made for a variety of natural and man-made catastrophes, high temperatures had rarely been considered a major hazard.

The catastrophe occurred in August, a month in which many people, including government ministers and physicians, are on holiday. Many bodies were not claimed for many weeks because relatives were on holiday. A refrigerated warehouse outside Paris was used by undertakers as they did not have enough space in their own facilities. On 3 September 2003, 57 bodies were still left unclaimed in the Paris area, and were buried.

The high number of deaths can be explained by the conjunction of seemingly unrelated events. Most nights in France are cool, even in summer. As a consequence, houses (usually of stone, concrete, or brick construction) do not warm too much during the daytime and radiate minimal heat at night, and air conditioning is usually unnecessary. During the heat wave, temperatures remained at record highs even at night, preventing the usual cooling cycle. Elderly persons living by themselves had never faced such extreme heat before and did not know how to react or were too mentally or physically impaired by the heat to make the necessary adaptations themselves. Elderly persons with family support or those residing in nursing homes were more likely to have others who could make the adjustments for them. This led to statistically improbable survival rates with the weakest group having fewer deaths than more physically fit persons; most of the heat victims came from the group of elderly persons not requiring constant medical care, and/or those living alone, without frequent contact with immediate family.

That shortcomings of the nation's health system could allow such a death toll is a matter of controversy in France. The administration of President Jacques Chirac and Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin laid the blame on families who had left their elderly behind without caring for them, the 35-hour workweek, which affected the amount of time doctors could work and family practitioners vacationing in August. Many companies traditionally closed in August, so people had no choice about when to vacation. Family doctors were still in the habit of vacationing at the same time. It is not clear that more physicians would have helped, as the main limitation was not the health system, but locating old people needing assistance.

The opposition, as well as many of the editorials of the local press, have blamed the administration. Many blamed Health Minister Jean-François Mattei for failing to return from his vacation when the heat wave became serious, and his aides for blocking emergency measures in public hospitals (such as the recalling of physicians). A particularly vocal critic was Dr. Patrick Pelloux, head of the union of emergency physicians, who blamed the Raffarin administration for ignoring warnings from health and emergency professionals and trying to minimize the crisis. Mattei lost his ministerial post in a cabinet reshuffle on 31 March 2004.

Not everyone blamed the government. "The French family structure is more dislocated than elsewhere in Europe, and prevailing social attitudes hold that once older people are closed behind their apartment doors or in nursing homes, they are someone else's problem," said Stéphane Mantion, an official with the French Red Cross. "These thousands of elderly victims didn't die from a heat wave as such, but from the isolation and insufficient assistance they lived with day in and out, and which almost any crisis situation could render fatal."[7]

Moreover, the French episode of heat wave in 2003 shows how heat wave dangers result from the intricate association of natural and social factors. Although research established that heat waves represent a major threat for public health, France had no policy in place. Until the 2003 event, heat waves were a strongly underestimated risk in the French context, which partly explains the high number of victims.[8]

Portugal

In Portugal, an estimated 1,866 to 2,039 people died of heat-related causes.[9] 1 August 2003, was the hottest day in centuries, with night temperatures well above 30 °C (86 °F). At dawn that same day, a freak storm developed in the southern region of the country. Over the next week, a hot, strong sirocco wind contributed to the spread of extensive forest-fires.[10][11] Five percent of Portugal's countryside and 10% of the forests (215,000 hectares[5] or an estimated 2,150 km2 (830 sq mi)), were destroyed, and 18 people died in the flames. In Amareleja, one of the hottest cities in Europe, temperatures reached as high as 48 °C (118 °F).

Netherlands

About 1,500[5][12] heat-related deaths occurred in the Netherlands, again largely the elderly. The heat wave broke no records, although four tropical weather-designated days in mid-July, preceding the official wave, are not counted due to a cool day in between and the nature of the Netherlands specification/definition of a heat wave.[12] The highest temperature recorded this heatwave was on 7 August, when in Arcen, in Limburg, a temperature of 37.8 °C was reached, 0.8 °C below the national record (since 1904). A higher temperature had only been recorded twice before. On 8 August, a temperature of 37.7 °C was recorded, and 12 August had a temperature of 37.2 °C.[13]

Spain

Initially, 141 deaths were attributed to the heat wave in Spain.[14] A further research of INE estimated a 12,963 excess of deaths during summer of 2003.[14] Temperature records were broken in various cities, with the heat wave being more felt in typically cooler northern Spain.

Record temperatures were felt in:

- Jerez, 45.1 °C (113.2 °F)

- Girona, 41 °C (106 °F)[15]

- Burgos, 38.8 °C (101.8 °F)[16]

- San Sebastián, 38.6 °C (101.5 °F)[16]

- Pontevedra, 36 °C (97 °F)[17]

- Barcelona, 36 °C (97 °F)[18]

- Sevilla, 45.2 °C (113.4 °F) (the 1995 record was 46.6 °C (115.9 °F))[19]

Italy

The summer of 2003 was among the warmest in the last three centuries,[20] and the maximum temperatures of July and August remained above 30 °C.[20] The high humidity intensified the perception of heat and population suffering.[20] Several reports about strong positive temperature anomalies exist — for instance from Toscana[21] and Veneto.[22] Temperatures rose far above average in most of the country and reached very high mean values especially in terms of heat persistence. The weather station of Catenanuova, in Sicily, had a monthly mean of 31.5 °C (88.7 °F) in July 2003, with an absolute maximum of 46.0 °C (114.8 °F) on 17 July, with monthly mean maximum temperatures of 36.0 °C (96.8 °F), 38.9 °C (102.0 °F) and 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) in June, July, and August 2003, respectively.[23]

Germany

In Germany, shipping could not navigate the Elbe or Danube. Around 300 people[5]—mostly elderly—died during the 2003 heatwave in Germany.

Switzerland

Melting glaciers in the Alps caused avalanches and flash floods in Switzerland. A new nationwide record temperature of 41.5 °C (106.7 °F) was recorded in Grono, Graubünden.[24]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom experienced a warm summer with temperatures well above average. However, Atlantic cyclones brought cool and wet weather for a short while at the end of July and beginning of August before the temperatures started to increase substantially from 3 August onwards. Several weather records were broken in the United Kingdom, including the UK's highest recorded temperature 38.5 °C (101.3 °F) at Faversham in Kent on 10 August. Scotland also broke its highest temperature record with 32.9 °C (91.2 °F) recorded in Greycrook in the Scottish borders on 9 August.[25] According to the BBC, around 2,000 more people than usual may have died in the United Kingdom during the 2003 heatwave.[26]

Ireland

The summer of 2003 was warmer than average in Ireland, but the heat was far less pronounced there than in the rest of Europe. August was by far the warmest, sunniest, and driest month, with temperatures roughly 2 °C above average. The highest temperature recorded was 30.3 °C (86.5 °F) at Belderrig, County Mayo on 8 August.[27][28][29]

Sweden

Remarkably, Scandinavia saw a cooler August in 2003 than the previous year when comparative temperatures were very high for the latitude, as the hot air parked over continental Europe. Only the deep southern Sweden saw any type of heatwave effect in the country, with the average high of Lund for August being 23.9 °C (75.0 °F), which is a very warm temperature average for August.[30] In spite of this the Scania County stayed below extremes of 30 °C (86 °F) indicating a more subtle kind of heat. The records from 1997 and 2002 held up all throughout the country, and the warmest temperature was 30.8 °C (87.4 °F) in Stockholm on August 1, which was higher than the warmest Irish temperature. Although a comparatively low exposure to the heatwave this is to be expected given the greater continental influence. When compared with the 1961-1990 averages the 2003 August month was still a couple of degrees warmer than a normal August in the southern third of the country.

The bulk of the heat wave in Sweden was instead seen earlier in July in the central and northerly parts of the country, where Stockholm had a July mean of 20.2 °C (68.4 °F) with a high of 25.4 °C (77.7 °F) which although very warm was not record-setting.[31] The warmest summer temperature was set on July 17 in the northern city of Piteå with 32.8 °C (91.0 °F), which although it is very hot for such a northerly coastal location, was largely unrelated to the latter central European intense heat wave. In northern Sweden, August temperatures are rarely warm due to the decreased exposure of the low but everlasting sun during the summer solstice. As a result, temperatures there peak in July if being a warm summer.

Effects on crops

Crops in Southern Europe suffered the most from drought.

Wheat

These shortfalls in wheat harvest occurred as a result of the long drought.

- France – 20%

- Italy – 13%

- United Kingdom – 12%

- Ukraine – 75% (unknown if affected by heatwave or an early freeze that year)

- Moldova – 80%

Many other countries had shortfalls of 5–10%, and the EU total production was down by 10 million tonnes, or 10%.

Grapes

The heatwave greatly accelerated the ripening of grapes; also, the heat dehydrated the grapes, making for more concentrated juice. By mid-August, the grapes in certain vineyards had already reached their optimal sugar content, possibly resulting in 12.0°–12.5° wines (see alcoholic degree). Because of that, and also of the impending change to rainy weather, the harvest was started much earlier than usual (e.g. in mid-August for areas that are normally harvested in September).

The wines from 2003, although in scarce quantity, are predicted to have exceptional quality, especially in France. The heatwave made Hungary fare extremely well in the Vinalies 2003 International wine contest: a total of nine gold and nine silver medals were awarded to Hungarian winemakers.[32]

Effects on the sea

The anomalous overheating affecting the atmosphere also created anomalies on sea surface stratification in the Mediterranean Sea and on the surface currents, as well. A seasonal current of the central Mediterranean Sea, the Atlantic Ionian Stream (AIS), was affected by the warm temperatures, resulting in modifications in its path and intensity. The AIS is important for the reproduction biology of important pelagic commercial fish species, so the heatwave may have influenced indirectly the stocks of these species.[33]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2003 european heat wave. |

- Heat wave

- Drought

- 2006 European heat wave

- 2010 Northern Hemisphere summer heat wave

- 2010 Sahel famine

- Summer 2012 North American heat wave

References

- ↑ WMO: Unprecedented sequence of extreme weather events – News – Professional Resources – PreventionWeb.net

- ↑ Robine, Jean-Marie; Cheung, Siu Lan K.; Le Roy, Sophie; Van Oyen, Herman; Griffiths, Clare; Michel, Jean-Pierre; Herrmann, François Richard (2008). "Death toll exceeded 70,000 in Europe during the summer of 2003". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 331 (2): 171–178. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2007.12.001. ISSN 1631-0691. PMID 18241810.

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20051013071340/http://www.met.reading.ac.uk/~swrmethn/summer2003/heatwave2003_reading_incfigs.pdf

- ↑ http://www.earth-policy.org/Updates/2006/Update56.htm Earth Policy Institute article; data for more countries: http://www.earth-policy.org/Updates/2006/Update56_data.htm

- 1 2 3 4 Archived 29 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ CIA-The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/fr.html Archived 14 February 2010 at WebCite

- ↑ www.time.com

- ↑ 32. Poumadère, M., Mays, C., Le Mer, S. and Blong, R. (2005), The 2003 Heat Wave in France: Dangerous Climate Change Here and Now. Risk Analysis, 25: 1483–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00694.x

- ↑ http://www.onsa.pt/conteu/onda_2003_relatorio.pdf

- ↑ "Portugal Diário" (in Portuguese). Portugaldiario.iol.pt. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ InterScience

- 1 2 "View Article". Eurosurveillance. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ KNMI, Klimatologie; Job Verkaik; Jon Nellestijn; Rob Sluijter. "KNMI – Daggegevens van het weer in Nederland". Archived from the original on 11 August 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- 1 2 "La ola de calor de 2003 coincidió con un incremento de 13.000 muertes". El País. Madrid. June 29, 2004. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ↑ History for Girona, Spain Weather Underground. 13 August 2003. Last Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- 1 2 "Valores extremos – Agencia Estatal de Meteorología – AEMET. Gobierno de España" (in Spanish). Aemet.es. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ History for Vigo, Spain. Weather Underground. August 2003. Last Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ↑ History for Barcelona, Spain. Weather Underground. 13 August 2003. Last Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ↑ "Agencia Estatal de Meteorología – AEMET. Gobierno de España" (PDF) (in Spanish). Inm.es. 27 February 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 "L'ondata di calore dell'estate 2003". Ministero della Salute, L'ondata di calore dell'estate 2003. Ministero della Salute. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ http://www.clima.ibimet.cnr.it/attachments/Sommario%20Clima%202003-Toscana.pdf

- ↑ (Analisi meteo-climatica inverno 2002/2003)

- ↑ "Table I – Daily temperature readings" (PDF). Osservatorio delle Acque (Water Monitoring) Annual data. Dipartimento dell'Acqua e dei Rifiuti. 2003. p. 45. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ "MeteoSwiss – Switzerland". Archived from the original on 3 May 2008.

- ↑ "Great weather events: Temperatures records fall in summer 2003". Met Office. 19 November 2008. Archived from the original on 16 May 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ "Deaths up by 2,000 in heatwave". BBC. 3 October 2003. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ Met Éireann – Monthly Weather Bulletin (June 2003)

- ↑ Met Éireann – Monthly Weather Bulletin (July 2003)

- ↑ Met Éireann – Monthly Weather Bulletin (August 2003)

- ↑ "Temperature & Cloud statistics for Sweden - August 2003" (PDF) (in Swedish). SMHI. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ "Temperature & Cloud statistics for Sweden - July 2003" (PDF) (in Swedish). SMHI. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ "Union des oenologues de France". Oenologuesdefrance.fr. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ "Effects of 2003 heatwave on the Sea Surface in Central Mediterranean". Ocean-sci.net. Retrieved 15 March 2010.