First Italo-Ethiopian War

| First Italo-Ethiopian War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Scramble for Africa | |||||||

Clockwise from top left: Italian soldiers en route to Massawa; castle of Yohannes IV at Mek'ele;[1] Ethiopian cavalry at the Battle of Adwa; Italian prisoners are freed following the end of hostilities; Menelik II at Adwa; Ras Makonnen leading Ethiopian troops in the Battle of Amba Alagi | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Armed and Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 18,000[2]–25,000[3] |

196,000[3]

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,000[2]–15,000 dead[5] | 17,000 dead[5] | ||||||

The First Italo-Ethiopian War was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from 1895 to 1896. It originated from a disputed treaty which, the Italians claimed, turned the country into an Italian protectorate. Much to their surprise, they found that Ethiopian ruler Menelik II, rather than opposed by some of his traditional enemies, was supported by them, and so the Italian army, invading Ethiopia from Italian Eritrea in 1893, faced a more united front than they expected. In addition, Ethiopia was supported by the United Kingdom, France, and Russia with military advisers, army training, and the sale of weapons for Ethiopian forces during the war in order to prevent Italy from becoming a colonial competitor.[6][7] Full-scale war broke out in 1895, with Italian troops having initial success until Ethiopian troops counterattacked Italian positions and besieged the Italian fort of Meqele, forcing its surrender. Italian defeat came about after the Battle of Adwa, where the Ethiopian army dealt the heavily outnumbered Italians a decisive loss and forced their retreat back into Eritrea.

This was not the first African victory over Western colonizers, but it was the first time such a military put a definitive stop to a colonizing nation's efforts. According to one historian, "In an age of relentless European expansion, Ethiopia alone had successfully defended its independence".[8]

Background

The Khedive of Egypt Isma'il Pasha, "Isma'il the Magnificent" had conquered Eritrea as part of his efforts to give Egypt an African empire.[9] Isma'il had tried to follow that conquest with Ethiopia, but the Egyptian attempts to conquer that realm ended in humiliating defeat. After Egypt's bankruptcy in 1876 followed by the Ansar revolt under the leadership of the Mahdi in 1881, the Egyptian position in Eritrea was hopeless with the Egyptian forces cut off and not been paid for years, and by 1884 when the Egyptians began to pull out of the Sudan, the Egyptians also left Eritrea.[10] Egypt had very much in the French sphere of influence until 1882 when Britain occupied Egypt. A major goal of French foreign policy until 1904 was to lever the British out of Egypt to restore it to its place in the French sphere of influence, and in 1883 the French created the colony of French Somaliland which allowed for the establishment of a French naval base at Djibouti on the Red Sea.[11] The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had turned the Horn of Africa into a very strategic region as a navy based in the Horn could interdict any shipping going up and down the Red Sea. By building naval bases on the Red Sea that could intercept British shipping in the Red Sea, the French hoped to reduce the value of the Suez Canal for the British, and thus lever them out of Egypt. On 3 June 1884, a treaty was signed between Britain, Egypt and Ethiopia that allowed the Ethiopians to occupy parts of Eritrea and allowed the Ethiopian goods to pass in and out of Massawa duty free.[12] From the viewpoint of Britain, it was highly undesirable that the French replace the Egyptians in Eritrea as that would allow the French to have naval bases on the Red Sea that could interfere with British shipping using the Suez Canal, and as the British did not want the financial burden of ruling Eritrea, they looked for an another power to replace the Egyptians.[13] After initially encouraging the Emperor Yohannes IV to move into Eritrea to replace the Egyptians, London decided to have the Italians move into Eritrea.[14] After the French had unexpectedly made Tunis into their protectorate in 1881, outraging opinion in Italy over the so-called "Schiaffo di Tunisi" (the "theft of Tunis"), Italian foreign policy had been extremely anti-French, and from the British viewpoint encouraging the Italians to conquer Eritrea was the best way of ensuring the Eritrean ports on Red Sea stayed out of French hands by having the staunchly anti-French Italians move in. In 1882, Italy had joined the Triple Alliance, allying herself with Austria and Germany against France. On 5 February 1885 Italian troops landed at Massawa to replace the Egyptians.[15] The Italian government for its part was more than happy to embark upon an imperialist policy to distract its people from the failings in post Risorgimento Italy.[16] In 1861, the unification of Italy was supposed to mark the beginning of a glorious new era in Italian life, and many Italians were gravely disappointed to find that not much had changed in the new Kingdom of Italy with the vast majority of Italians still living in abject poverty. To compensate, a chauvinist mood was rampant in Italy with the newspaper Il Diritto writing in an editorial: "Italy must be ready. The year 1885 will decide her fate as a great power. It is necessary to feel the responsibility of the new era; to become again strong men afraid of nothing, with the sacred love of the fatherland, of all Italy, in our hearts".[17]

On March 25, 1889, the Shewa ruler Menelik II, having conquered Tigray and Amhara, declared himself Emperor of Ethiopia (or "Abyssinia", as it was commonly called in Europe at the time). Barely a month later, on May 2, he signed the Treaty of Wuchale with the Italians, which apparently gave them control over Eritrea, the Red Sea coast to the northeast of Ethiopia, in return for recognition of Menelik's rule. Menelik II continued the policy of Tewodros I of integrating Ethiopia.

However, the bilingual treaty did not say the same thing in Italian and Amharic; the Italian version did not give the Ethiopians the "significant autonomy" written into the Amharic translation.[18] The former text established an Italian protectorate over Ethiopia, but the Amharic version merely stated that Menelik could contact foreign powers and conduct foreign affairs through Italy if he so chose. Italian diplomats, however, claimed that the original Amharic text included the clause and Menelik knowingly signed a modified copy of the Treaty.[19] In October 1889, the Italians informed all of the other European governments because of the Treaty of Wuchale that Ethiopia was now an Italian protectorate and therefore the other European nations could not conduct diplomatic relations with Ethiopia.[20] With the exceptions of the Ottoman Empire, which still maintained its claim to Eritrea and Russia which disliked the idea of an Eastern Orthodox nation being subjugated to a Roman Catholic nation, all of the European powers accepted the Italian claim to a protectorate.[21] The Italian claim that Menelik was aware of Article XVII turning his nation into an Italian protectorate seems unlikely given that the Emperor Menelik sent letters to Queen Victoria and Emperor Wilhelm II in late 1889 and was informed in the replies in early 1890 that neither Britain nor Germany could have diplomatic relations with Ethiopia on the account of Article XVII of the Treaty of Wuchale, a revelation that came as a great shock to the Emperor.[22] Victoria's letter was polite whereas Wilhelm's letter was somewhat more rude, saying that King Umberto I was a great friend of Germany and Menelik's violation of the supposed Italian protectorate was a grave insult to Umberto, adding that he never wanted to hear from Menelik again.[23] Moreover, Menelik did not know Italian and only signed the Amharic text of the treaty, being assured that there were no differences between the Italian and Amharic texts before he signed.[24] The differences between the Italian and Amharic texts was due to the Italian minister in Addis Ababa, Count Pietro Antonelli who had been instructed by his government to gain as much territory as possible in negotiating with the Emperor Menelik, but knowing Menelik was now enthroned as the King of Kings had a strong position was in the unenviable situation of negotiating a treaty that his own government might disallow, and who inserted the statement Ethiopia gave up it's right to conduct its foreign affairs to Italy as a way of pleasing his superiors who might otherwise had fired him for only making small territorial gains.[25] Antonelli was fluent in Amharic and given that Menelik only signed the Amharic text he could not have been unaware that the Amharic version of Article XVII only stated that the King of Italy places the services of his diplomats at the disposal of the Emperor of Ethiopia to represent him abroad if he so wished.[26] When his subterfuge was exposed in 1890 with Menelik indigently saying he would never sign away his country's independence to anybody, Antonelli who left Addis Ababa in mid 1890 resorted to racism, telling his superiors in Rome that as Menelik was a black man, he was thus intrinsically dishonest and it was only natural the Emperor would lie about the protectorate he supposedly willingly turned his nation into.[27]

Francesco Crispi, the Italian Prime Minister was an ultra-imperialist who believed the newly unified Italian state required "the grandeur of a second Roman empire".[28] Crispi believed that the Horn of Africa was the best place for the Italians to start building the new Roman empire.[29] The American journalist James Perry wrote that "Crispi was a fool, a bigot and a very dangerous man".[30] Because of the Ethiopian refusal to abide by the Italian version of the treaty and despite economic handicaps at home, the Italian government decided on a military solution to force Ethiopia to abide by the Italian version of the treaty. In doing so, they believed that they could exploit divisions within Ethiopia and rely on tactical and technological superiority to offset any inferiority in numbers.

There was a broader, European background as well: the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria–Hungary, and Italy was under some stress, with Italy being courted by England. Two secret Anglo-Italian protocols in 1891, left most of Ethiopia in Italy's sphere of influence.[31] France, one of the members of the opposing Franco-Russian Alliance, had its own claims on Eritrea and was bargaining with Italy over giving up those claims in exchange for a more secure position in Tunisia. Meanwhile, Russia was supplying weapons and other aid to Ethiopia.[18] It had been trying to gain a foothold in Ethiopia,[32] and in 1894, after denouncing the Treaty of Wuchale in July, it received an Ethiopian mission in St. Petersburg and sent arms and ammunition to Ethiopia.[33] This support continued after the war ended.[34] Germany and Austria supported their ally in the Triple Alliance Italy while France and Russia supported Ethiopia.

Opening phase

In 1893, judging that his power over Ethiopia was secure, Menelik repudiated the treaty; in response the Italians ramped up the pressure on his domain in a variety of ways, including the annexation of small territories bordering their original claim under the Treaty of Wuchale, and finally culminating with a military campaign and across the Mareb River into Tigray (on the border with Eritrea) in December 1894. The Italians expected disaffected potentates like Negus Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam, Ras Mengesha Yohannes, and the Sultan of Aussa to join them; instead, all of the ethnic Tigrayan or Amharic peoples flocked to the Emperor Menelik's side in a display of both nationalism and anti-Italian feeling, while other peoples of dubious loyalty (e.g. the Sultan of Aussa), were watched by Imperial garrisons.[35] In June 1894, Mengesha and his generals had appeared in Addis Ababa carrying large stones (a symbol of submission in Ethiopian culture) which they dropped before the Emperor Menelik.[36] In Ethiopia, the popular saying at the time was: "Of a black snake's bite, you may be cured, but from the bite of a white snake, you will never recover."[37] Further, Menelik had spent much of the previous four years building up a supply of modern weapons and ammunition, acquired from the French, British, and the Italians themselves, as the European colonial powers sought to keep each other's North African aspirations in check. They also used the Ethiopians as a proxy army against the Sudanese Mahdists.

In December 1894, Bahta Hagos led a rebellion against the Italians in Akkele Guzay, claiming support of Mengesha. Units of General Oreste Baratieri's army under Major Pietro Toselli crushed the rebellion and killed Bahta at the Battle of Halai. The Italian army then occupied the Tigrian capital, Adwa. Baratieri suspected that Mengesha would invade Eritrea, and met him at the Battle of Coatit in January 1895. The victorious Italians chased a retreating Mengesha, capturing weapons and important documents proving his complicity with Menelik. The victory in this campaign, along with previous victories against the Sudanese Mahdists, led the Italians to underestimate the difficulties to overcome in a campaign against Menelik.[38] At this point, Emperor Menelik turned to France, offering a treaty of alliance; the French response was to abandon the Emperor to secure Italian approval of the Treaty of Bardo which would secure French control of Tunisia. Virtually alone, on 17 September 1895, Emperor Menelik issued a proclamation calling up the men of Shewa to join his army at Were Ilu.[39]

As the Italians were poised to enter Ethiopian territory, the Ethiopians underwent mass mobilization all over the country.[40] Helping it was the newly updated imperial fiscal and taxation system. As a result, a hastily mobilized army of 196,000 men, in which more than half were armed with modern rifles, gathered from all parts of Abyssinia rallied at Addis Ababa in support of the Emperor and defense of their country.[3]

The unique Eurasian ally of Ethiopia was Russia.[6][33][34] The Ethiopian emperor sent his first diplomatic mission to St. Petersburg in 1895. In June 1895, the newspapers in St. Petersburg wrote, "Along with the expedition, Menelik II sent his diplomatic mission to Russia, including his princes and his bishop". Many citizens of the capital came to meet the train that brought Prince Damto, General Genemier, Prince Belyakio, Bishop of Harer Gabraux Xavier and other members of the delegation to St. Petersburg. On the eve of War, an agreement about rendering the military help for Ethiopia was concluded.[41][42]

The next clash came at Amba Alagi on 7 December 1895, when Ethiopian soldiers overran the Italian positions dug in on the natural fortress, and forced the Italians to retreat back to Eritrea. The remaining Italian troops under General Giuseppe Arimondi reached the unfinished Italian fort at Meqele. Arimondi left there a small garrison of approximately 1,150 askaris and 200 Italians, commanded by Major Giuseppe Galliano, and took the bulk of his troops to Adigrat, where Oreste Baratieri, the Italian commander, was concentrating the Italian Army.

The first Ethiopian troops reached Meqele in the following days. Ras Makonnen surrounded the fort at Meqele on 18 December, but the Italian commander adroitly used promises of a negotiated surrender to prevent the Ras from attacking the fort. By the first days of January, Emperor Menelik, accompanied by his Queen Taytu Betul, had led large forces into Tigray, and besieged the Italians for sixteen days (6–21 January 1896), making several unsuccessful attempts to carry the fort by storm, until the Italians surrendered with permission from the Italian Headquarters. Menelik allowed them to leave Meqele with their weapons, and even provided the defeated Italians mules and pack animals to rejoin Baratieri.[43] While some historians read this generous act as a sign that Emperor Menelik still hoped for a peaceful resolution to the war, Harold Marcus points out that this escort allowed him a tactical advantage: "Menelik craftily managed to establish himself in Hawzien, at Gendepata, near Adwa, where the mountain passes were not guarded by Italian fortifications."[44]

Heavily outnumbered, Baratieri refused to engage, knowing that due to their lack of infrastructure the Ethiopians could not keep large numbers of troops in the field much longer. However, Baratieri also never knew about the true numerical strength of the Ethiopian army that was to face his army, so he rather further fortified his positions in the Tigray. But the Italian government of Francesco Crispi was unable to accept being stymied by non-Europeans. The prime minister specifically ordered Baratieri to advance deep into enemy territory and bring about a battle.

Battle of Adwa

The decisive battle of the war was the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896, which took place in mountainous country north of the actual town of Adwa (or Adowa). The Italian army comprised four brigades totalling approximately 17,700 men, with fifty-six artillery pieces; the Ethiopian army comprised several brigades numbering between 73,000 and 120,000 men (80–100,000 with firearms: according to Pankhurst, the Ethiopians were armed with approximately 100,000 rifles of which about half were "fast firing"),[4] with almost fifty artillery pieces.

General Baratieri planned to surprise the larger Ethiopian force with an early morning attack, expecting his enemy to be asleep. However, the Ethiopians had risen early for Church services and, upon learning of the Italian advance, promptly attacked. The Italian forces were hit by wave after wave of attacks, until Menelik released his reserve of 25,000 men, destroying an Italian brigade. Another brigade was cut off, and destroyed by a cavalry charge. The last two brigades were destroyed piecemeal. By noon, the Italian survivors were in full retreat.

While Menelik's victory was in a large part due to sheer force of numbers, his troops were well-armed because of his careful preparations. The Ethiopian army only had a feudal system of organization, but proved capable of properly executing the strategic plan drawn up in Menelik's headquarters. However, the Ethiopian army also had its problems. The first was the quality of its arms, as the Italian and British colonial authorities could sabotage the transportation of 30,000–60,000 modern Mosin–Nagant rifles and Berdan rifles from Russia into landlocked Ethiopia. Secondly, the Ethiopian army's feudal organization meant that nearly the entire force was composed of peasant militia. Russian military experts advising Menelik II suggested a full contact battle with Italians, to neutralize the Italian fire superiority, instead of engaging in a campaign of harassment designed to nullify problems with arms, training, and organization.[42][45]

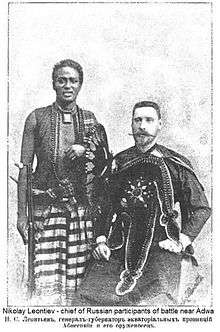

Some Russian councilors of Menelik II and a team of fifty Russian volunteers participated in the battle, among them Nikolay Leontiev, an officer of the Kuban Cossack army.[46] Russian support for Ethiopia also led to a Russian Red Cross mission, which arrived in Addis Ababa some three months after Menelik's Adwa victory.[47]

The Italians suffered about 7,000 killed and 1,500 wounded in the battle and subsequent retreat back into Eritrea, with 3,000 taken prisoner; Ethiopian losses have been estimated around 4,000–5,000 killed and 8,000 wounded.[48][49] In addition, 2,000 Eritrean askaris were killed or captured. Italian prisoners were treated as well as possible under difficult circumstances, but 800 captured askaris, regarded as traitors by the Ethiopians, had their right hands and left feet amputated.[50]

Outcome and consequences

Menelik retired in good order to his capital, Addis Ababa, and waited for the fallout of the victory to hit Italy. The casualty rate suffered by Italian forces at the Battle of Adwa was greater than any other major European battle of the 19th century, beyond even the Napoleonic Era's Waterloo and Eylau.[51] Riots broke out in several Italian cities, and within two weeks, the Crispi government collapsed amidst Italian disenchantment with "foreign adventures".[51]

Menelik secured the Treaty of Addis Ababa in October, which delineated the borders of Eritrea and forced Italy to recognize the independence of Ethiopia. Delegations from the United Kingdom and France—whose colonial possessions lay next to Ethiopia—soon arrived in the Ethiopian capital to negotiate their own treaties with this newly proven power.

Gallery

-

Russian military officer Nikolay Leontiev with a member of the Ethiopian military

-

An Ethiopian painting commemorating the Battle of Adwa

-

Two Italian soldiers captured and held captive after the Battle of Adwa.

See also

- British Expedition to Abyssinia (1868)

- Battle of Dogali (1887)

- Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–36)

- Italian Empire

- Military history of Ethiopia

Notes

References

- ↑ "Ethiopian Treasures". ethiopiantreasures.co.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- 1 2 Vandervort, Bruce. Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa, 1830–1914. 1998, page 160

- 1 2 3 First Italo-Abyssinian War: Battle of Adowa

- 1 2 Pankhurst, The Ethiopians, p. 190

- 1 2 The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism. 2005, page 71.

- 1 2 Patman, Robert G. (2009). The Soviet Union in the Horn of Africa: The Diplomacy of Intervention and Disengagement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–30. ISBN 9780521102513.

- ↑ "Menelik II". Gale. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ Jonas, Raymond (2011). The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire. Harvard UP. p. 1. ISBN 9780674062795.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 196.

- 1 2 Gardner, Hall (2015). The Failure to Prevent World War I: The Unexpected Armageddon. Ashgate. p. 107. ISBN 9781472430588.

- ↑ Piero Pastoretto. "Battaglia di Adua" (in Italian). Archived from the original on May 31, 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-04.

- ↑ Rubenson, Sven "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty" pages 243-283 from The Journal of African History Vol. 5, No. 2, 1964 page 244.

- ↑ Rubenson, Sven "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty" pages 243-283 from The Journal of African History Vol. 5, No. 2, 1964 pages 244-245.

- ↑ Rubenson, Sven "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty" pages 243-283 from The Journal of African History Vol. 5, No. 2, 1964 pages 248-249.

- ↑ Rubenson, Sven "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty" pages 243-283 from The Journal of African History Vol. 5, No. 2, 1964 page 249.

- ↑ Rubenson, Sven "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty" pages 243-283 from The Journal of African History Vol. 5, No. 2, 1964 page 257.

- ↑ Rubenson, Sven "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty" pages 243-283 from The Journal of African History Vol. 5, No. 2, 1964 pages 279-280.

- ↑ Rubenson, Sven "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty" pages 243-283 from The Journal of African History Vol. 5, No. 2, 1964 page 280.

- ↑ Rubenson, Sven "The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty" pages 243-283 from The Journal of African History Vol. 5, No. 2, 1964 page 280.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 201.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 201.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 201.

- ↑ Britain Gave Italy Rights Under Secret Pact in 1891 To Rule Most of Ethiopia, The New York Times, July 22, 1935

- ↑ Burke, Edmund (1892). "East Africa". The Annual Register of World Events: A Review of the Year. Longmans, Green. pp. 397–. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- 1 2 Vestal, Theodore M. (2005). "Reflections on the Battle of Adwa and its Significance for Today". In Paulos Milkias. The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism. Getachew Metaferia. Algora. pp. 21–35. ISBN 9780875864143.

- 1 2 Eribo, Festus (2001). In Search of Greatness: Russia's Communications with Africa and the World. Greenwood. p. 55. ISBN 9781567505320.

- ↑ Prouty, Chris (1986). Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia 1883–1910. Trenton: The Red Sea Press. p. 143.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 201.

- ↑ Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks 2005 page 201.

- ↑ Berkeley, George (1969). The campaign of Adowa and the rise of Menelik. Negro University Press (reprint). ISBN 1-56902-009-4.

- ↑ Marcus, Harold G. (1995). The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844–1913. Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press. p. 160. ISBN 1-56902-010-8.

- ↑ http://www.ethiopiancrown.org/adwa.htm

- ↑ "Russian mission to Abyssinia". 28 February 1895.

- 1 2 "Who Was Count Abai?". St.Petersburg: through centuries.

- ↑ Prouty, Empress Taytu, pp. 144–151.

- ↑ Harold G. Marcus (1975), The life and times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844-1913, p. 167 (ISBN 1569020094)

- ↑ "Cossacks of the emperor Мenelik II". tvoros.ru. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ↑ The activities of the officer the Kuban Cossack army N. S. Leontjev in the Italian-Ethiopic war in 1895–1896 (Russian)

- ↑ Richard, Pankhurst. "Ethiopia's Historic Quest for Medicine, 6". The Pankhurst History Library.

- ↑ von Uhlig, Encyclopaedia, p. 109.

- ↑ Pankhurst. The Ethiopians, pp. 191–2.

- ↑ Augustus B. Wylde, Modern Abyssinia (London: Methuen, 1901), p. 213

- 1 2 Vandervort, Bruce. Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa, 1830–1914. 1998, page 164.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Italo-Ethiopian War. |

.svg.png)