Italian Empire

Italian Empire |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

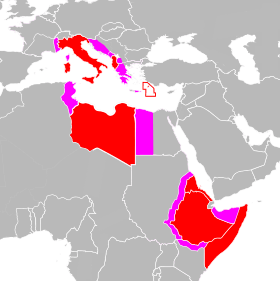

.svg.png) Kingdom of Italy Colonies of Italy in 1939

Territories occupied during World War II |

||||

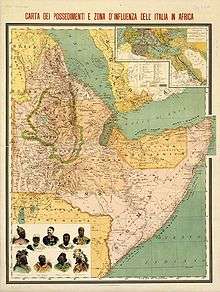

The Italian Empire (Italian: Impero Italiano) comprised the colonies, protectorates, concessions, dependencies and trust territories of the Kingdom of Italy and, after 1946, the Italian Republic. The genesis of the Italian colonial empire was the purchase, in 1869, by a commercial company of the coastal town of Assab on the Red Sea. This was taken over by the Italian government in 1882, becoming Italy's first overseas territory. Over the next two decades the pace of European acquisitions in Africa increased, causing the so-called "Scramble for Africa". By the start of the First World War in 1914, Italy had acquired in Africa alone a colony on the Red Sea coast (Eritrea), a large protectorate in Somalia and administrative authority in formerly Turkish Libya. Outside of Africa, Italy possessed a small concession in Tientsin in China and the Dodecanese Islands off the coast of Turkey.

From early in the "scramble", Italy had designs on the Ethiopian Empire, but was twice defeated in the 19th century: first at the Battle of Dogali in 1887 and then in the first invasion of Ethiopia in 1895–96. During the First World War, Italy occupied southern Albania to prevent it from falling to Austria-Hungary. In 1917, it established a protectorate over Albania, which remained in place until 1920.[1] The Fascist government that came to power with Benito Mussolini in 1922 sought to increase the size of the Italian empire and to satisfy the claims of Italian irredentists. In 1935–36, in its second invasion of Ethiopia Italy was successful and it merged its new conquest with its older east African colonies to create Italian East Africa. In 1939, Italy invaded Albania and incorporated it into the Fascist state. During the Second World War (1939–45), Italy made several conquests and annexations, but was forced in the final peace to abandon all its colonies and protectorates. It was granted a United Nations trust to administer former Italian Somaliland in 1950. When Somalia became independent in 1960, Italy's eight-decade experience with colonialism ended.

History

Scramble for an empire

The unification of Italy brought with it a belief that Italy deserved its own overseas empire, alongside those of the other powers of Europe, and a rekindling of the notion of mare nostrum.[2] However, Italy had arrived late to the colonial race, and its relative weakness in international affairs meant that it was dependent on the acquiescence of Britain, France and Germany towards its empire-building.[3]

Italy had long considered the Ottoman province of Tunisia, where a large community of Tunisian Italians lived, within its economic sphere of influence. It did not consider annexing it until 1879, when it became apparent that Britain and Germany were encouraging France to add it to its colonial holdings in North Africa.[4] A last minute offer by Italy to share Tunisia between the two countries was refused, and France, confident in German support, ordered its troops in from French Algeria, imposing a protectorate over Tunisia in May 1881 under the Treaty of Bardo.[5] The shock of the "Tunisian bombshell", as it was referred to in the Italian press, and the sense of Italy's isolation in Europe, led it into signing the Triple Alliance in 1882 with Germany and Austria-Hungary.[6]

Italy's search for colonies continued until February 1886, when, by secret agreement with Britain, it annexed the port of Massawa in Eritrea on the Red Sea from the crumbling Egyptian Empire. Italian annexation of Massawa denied the Ethiopian Empire of Yohannes IV an outlet to the sea[7] and prevented any expansion of French Somaliland.[8] At the same time, Italy occupied territory on the south side of the horn of Africa, forming what would become Italian Somaliland.[9] However, Italy coveted Ethiopia itself and, in 1887, Italian Prime Minister Agostino Depretis ordered an invasion. This invasion was halted after the loss of five hundred Italian troops at the Battle of Dogali.[10] Depretis's successor, Prime Minister Francesco Crispi signed the Treaty of Wuchale in 1889 with Menelik II, the new emperor. This treaty ceded Ethiopian territory around Massawa to Italy to form the colony of Eritrea, and — at least, according to the Italian version of the treaty — made Ethiopia an Italian protectorate.[11] Relations between Italy and Menelik deteriorated over the next few years until the First Italo-Ethiopian War broke out in 1895, when Crispi ordered Italian troops into the country. Outnumbered and poorly equipped,[12] the result was a humiliating defeat for Italy at the hands of Ethiopian forces at the Battle of Adwa in 1896.[13]

On 7 September 1901, a concession in Tientsin was ceded to the Kingdom of Italy by Imperial China. It was administered by Rome's Consul. Several ships of the Italian Royal Navy (Regia Marina) were based at Tientsin.[14]

A wave of nationalism that swept Italy at the turn of the 20th century led to the founding of the Italian Nationalist Association, which pressed for the expansion of Italy's empire. Newspapers were filled with talk of revenge for the humiliations suffered in Ethiopia at the end of the previous century, and of nostalgia for the Roman era. Libya, it was suggested, as an ex-Roman colony, should be "taken back" to provide a solution to the problems of Southern Italy's population growth. Fearful of being excluded altogether from North Africa by Britain and France, and mindful of public opinion, Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti ordered the declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire, of which Libya was part, in October 1911.[15] As a result of the Italo-Turkish War, Italy gained Libya and the Dodecanese Islands.

World War I and aftermath

In 1915, Italy agreed to enter World War I on the side of Britain and France; and, in return, was guaranteed territory at the Treaty of London, both in Europe and, should Britain and France gain Germany's African possessions, in Africa.[16]

Prior to direct intervention in World War I, Italy occupied the Albanian port of Vlorë in December 1914.[1] In the fall of 1916, Italy started to occupy southern Albania.[1] In 1916, Italian forces recruited Albanian irregulars to serve alongside them.[1] Italy, with permission of the Allied command, occupied Northern Epirus on 23 August 1916, forcing the neutralist Greek Army to withdraw its occupation forces from there.[1] In June 1917, Italy proclaimed central and southern Albania as a protectorate of Italy while Northern Albania was allocated to the states of Serbia and Montenegro.[1] By 31 October 1918, French and Italian forces expelled the Austro-Hungarian Army from Albania.[1]

Dalmatia was a strategic region during World War I that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. The Treaty of London guaranteed Italy the right to annex a large portion of Dalmatia in exchange for Italy's participation on the Allied side. From 5–6 November 1918, Italian forces were reported to have reached Lissa, Lagosta, Sebenico, and other localities on the Dalmatian coast.[17] By the end of hostilities in November 1918, the Italian military had seized control of the entire portion of Dalmatia that had been guaranteed to Italy by the Treaty of London and by 17 November had seized Fiume as well.[18] In 1918, Admiral Enrico Millo declared himself Italy's Governor of Dalmatia.[18] Famous Italian nationalist Gabriele d'Annunzio supported the seizure of Dalmatia, and proceeded to Zara (today's Zadar) in an Italian warship in December 1918.[19]

However, at the concluding Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Italy received less in Europe than had been promised, and none overseas. In April 1920, it was agreed between the British and Italian foreign ministers that Jubaland would be Italy's compensation, but Britain held back on the deal for several years, aiming to use it as leverage to force Italy to cede the Dodecanese to Greece.[20]

Fascism and the Italian Empire

In 1922, the leader of the Italian fascist movement, Benito Mussolini, became Prime Minister of Italy after the March on Rome. Mussolini resolved the question of sovereignty over the Dodecanese at the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which formalized Italian administration of both Libya and the Dodecanese Islands, in return for a payment to Turkey, the successor state to the Ottoman Empire, though he failed in an attempt to extract a mandate of a portion of Iraq from Britain.

The month following the ratification of the Lausanne treaty, Mussolini ordered the invasion of the Greek island of Corfu after the Corfu incident. The Italian press supported the move, noting that Corfu had been a Venetian possession for four hundred years. The matter was taken by Greece to the League of Nations, where Mussolini was convinced by Britain to evacuate Italian troops, in return for reparations from Greece. The confrontation led Britain and Italy to resolve the question of Jubaland in 1924, which was merged into Italian Somaliland.[21]

During the late 1920s, imperial expansion became an increasingly favoured theme in Mussolini's speeches.[22] Amongst Mussolini's aims were that Italy had to become the dominant power in the Mediterranean that would be able to challenge France or Britain, as well as attain access to the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.[22] Mussolini alleged that Italy required uncontested access to the world's oceans and shipping lanes to ensure its national sovereignty.[23] This was elaborated on in a document he later drew up in 1939 called "The March to the Oceans", and included in the official records of a meeting of the Grand Council of Fascism.[23] This text asserted that maritime position determined a nation's independence: countries with free access to the high seas were independent; while those who lacked this, were not. Italy, which only had access to an inland sea without French and British acquiescence, was only a "semi-independent nation", and alleged to be a "prisoner in the Mediterranean":[23]

"The bars of this prison are Corsica, Tunisia, Malta, and Cyprus. The guards of this prison are Gibraltar and Suez. Corsica is a pistol pointed at the heart of Italy; Tunisia at Sicily. Malta and Cyprus constitute a threat to all our positions in the eastern and western Mediterrean. Greece, Turkey, and Egypt have been ready to form a chain with Great Britain and to complete the politico-military encirclement of Italy. Thus Greece, Turkey, and Egypt must be considered vital enemies of Italy's expansion ... The aim of Italian policy, which cannot have, and does not have continental objectives of a European territorial nature except Albania, is first of all to break the bars of this prison ... Once the bars are broken, Italian policy can only have one motto – to march to the oceans."— Benito Mussolini, The March to the Oceans[23]

In the Balkans, the Fascist regime claimed Dalmatia and held ambitions over Albania, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Vardar Macedonia, and Greece based on the precedent of previous Roman dominance in these regions.[24] Dalmatia and Slovenia were to be directly annexed into Italy while the remainder of the Balkans was to be transformed into Italian client states.[25] The regime also sought to establish protective patron-client relationships with Austria, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria.[24]

In both 1932 and 1935, Italy demanded a League of Nations mandate of the former German Cameroon and a free hand in Ethiopia from France in return for Italian support against Germany (see Stresa Front).[26] This was refused by French Prime Minister Édouard Herriot, who was not yet sufficiently worried about the prospect of a German resurgence.[26] The failed resolution of the Abyssinia Crisis led to the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, in which Italy annexed Ethiopia to its empire.

Italy's stance towards Spain shifted between the 1920s and the 1930s. The Fascist regime in the 1920s held deep antagonism towards Spain due to Miguel Primo de Rivera's pro-French foreign policy. In 1926, Mussolini began aiding the Catalan separatist movement, which was led by Francesc Macià, against the Spanish government.[27] With the rise of the left-wing Republican government replacing the Spanish monarchy, Spanish monarchists and fascists repeatedly approached Italy for aid in overthrowing the Republican government, in which Italy agreed to support them in order to establish a pro-Italian government in Spain.[27] In July 1936, Francisco Franco of the Nationalist faction in the Spanish Civil War requested Italian support against the ruling Republican faction, and guaranteed that, if Italy supported the Nationalists, "future relations would be more than friendly" and that Italian support "would have permitted the influence of Rome to prevail over that of Berlin in the future politics of Spain".[28] Italy intervened in the civil war with the intention of occupying the Balearic Islands and creating a client state in Spain.[29] Italy sought the control of the Balearic Islands due to its strategic position – Italy could use the islands as a base to disrupt the lines of communication between France and its North African colonies and between British Gibraltar and Malta.[30] After the victory by Franco and the Nationalists in the war, Allied intelligence was informed that Italy was pressuring Spain to permit an Italian occupation of the Balearic Islands.[31]

After the United Kingdom signed the Anglo-Italian Easter Accords in 1938, Mussolini and foreign minister Ciano issued demands for concessions in the Mediterranean by France, particularly regarding Djibouti, Tunisia and the French-run Suez Canal.[32] Three weeks later, Mussolini told Ciano that he intended for Italy to demand an Italian takeover of Albania.[32] Mussolini professed that Italy would only be able to "breathe easily" if it had acquired a contiguous colonial domain in Africa from the Atlantic to the Indian Oceans, and when ten million Italians had settled in them.[22] In 1938, Italy demanded a sphere of influence in the Suez Canal in Egypt, specifically demanding that the French-dominated Suez Canal Company accept an Italian representative on its board of directors.[33] Italy opposed the French monopoly over the Suez Canal because, under the French-dominated Suez Canal Company, all Italian merchant traffic to its colony of Italian East Africa was forced to pay tolls on entering the canal.[33]

In 1939, Italy invaded and captured Albania and made it a part of the Italian Empire as a separate kingdom in personal union with the Italian crown. The region of modern-day Albania had been an early part of the Roman Empire, which had actually been held before northern parts of Italy had been taken by the Romans, but had long since been populated by Albanians, even though Italy had retained strong links with the Albanian leadership and considered it firmly within its sphere of influence.[34] It is possible that Mussolini simply wanted a spectacular success over a smaller neighbour to match Germany's absorption of Austria and Czechoslovakia.[34] Italian King Victor Emmanuel III took the Albanian crown, and a fascist government under Shefqet Verlaci was established to rule over Albania.

World War II

Mussolini entered World War II on the side of Adolf Hitler with plans to enlarge Italy's territorial holdings. He had designs on an area of western Yugoslavia, southern France, Corsica, Malta, Tunisia, part of Algeria, an Atlantic port in Morocco, French Somaliland and British Egypt and Sudan.[36] Mussolini also mentioned to Italo Balbo his ambitions of capturing British and French territories in the Cameroons and founding an Italian Cameroon, in the hope that Italy could establish a colony on the Atlantic coast of Africa.

On 10 June 1940, Mussolini declared war on Britain and France; both countries had been at war with Nazi Germany since September of the previous year. In July 1940, Italian foreign minister Count Ciano presented Hitler with a document of Italy's demands that included: the annexation of Corsica, Nice, and Malta; protectorates in Tunisia and a buffer zone in Algeria; independence with Italian military presence and bases in Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Transjordan as well as expropriation of oil companies in those territories; military occupation of Aden, Perim and Sokotra; Cyprus given to Greece in exchange for Corfu and Ciamuria given to Italy; Italy is given British Somaliland, Djibuti, French Equatorial Africa up to Chad, as well as Ciano adding at the meeting that Italy wanted Kenya and Uganda as well.[37] Hitler accepted the document without any comment.[37]

In October 1940, Mussolini ordered the invasion of Greece from Albania, but the operation was unsuccessful.[38] In April 1941, Germany launched an invasion of Yugoslavia and then attacked Greece. Italy and other German allies supported both actions. The German and Italian armies overran Yugoslavia in about two weeks and, despite British support in Greece, the Axis troops overran that country by the end of April. The Italians gained control over portions of both occupied Yugoslavia and occupied Greece. A member of the House of Savoy, Prince Aimone, 4th Duke of Aosta, was appointed king of the newly created Independent State of Croatia.

During the height of the Battle of Britain, the Italians launched an attack on Egypt in the hope of capturing the Suez Canal. By 16 September 1940, the Italians advanced 60 miles across the border. However, in December, the British launched Operation Compass and, by February 1941, the British had cut off and captured the Italian 10th Army and had driven deep into Libya.[39] A German intervention prevented the fall of Libya and the combined Axis attacks drove the British back into Egypt until summer 1942, before being stopped at El Alamein. Allied intervention against Vichy French-held Morocco and Algeria created a two-front campaign. German and Italian forces entered Tunisia in late 1942 in response, however forces in Egypt were soon forced to make a major retreat into Libya. By May 1943, Axis forces in Tunisia were forced to surrender.

The East African Campaign started with Italian advances into British-held Kenya, British Somaliland, and Sudan. In the summer of 1940, Italian armed forces successfully invaded all of British Somaliland.[40] But, by the end of 1941, the British had counter-attacked and pushed deep into Italian East Africa. By 5 May, Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia had returned to Addis Ababa to reclaim his throne. In November, the last organised Italian resistance ended with the fall of Gondar.[41] However, following the surrender of East Africa, some Italians conducted a guerrilla war which lasted for two more years.

In November 1942, when the Germans occupied Vichy France during Case Anton, Italian-occupied France was expanded with the occupation of Corsica.

End of the empire

By the autumn of 1943, the Italian Empire and all dreams of an Imperial Italy effectively came to an end. On 7 May, the surrender of Axis forces in Tunisia and other near continuous Italian reversals, led King Victor Emmanuel III to plan the removal of Mussolini. Following the Invasion of Sicily, all support for Mussolini evaporated. A meeting of the Grand Council of Fascism was held on 24 July, which managed to impose a vote of no confidence to Mussolini. The "Duce" was subsequently deposed and arrested by the King on the following afternoon. Afterwards, Mussolini remained a prisoner of the King until 12 September, when, on the orders of Hitler, he was rescued by German paratroops and became leader of the newly established Italian Social Republic.

After 25 July, the new Italian government under the King and Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio remained outwardly part of the Axis. But, secretly, it started negotiations with the Allies. On the eve of the American landings at Salerno, which started the Allied invasion of Italy, the new Italian government secretly signed an armistice with the Allies. On 8 September, the armistice was made public. In Albania, Yugoslavia, the Dodecanese, and other territories still held by the Italians, German military forces successfully attacked their former Italian allies and ended Italy's rule. During the Dodecanese Campaign, an Allied attempt to take the Dodecanese with the cooperation of the Italian troops ended in total German victory. In China, the Imperial Japanese Army occupied Italy's concession in Tientsin after getting news of the armistice. Later in 1943 the Italian Social Republic formally ceded control of the concession to Japan's puppet regime in China, the Reorganized National Government of China under Wang Jingwei.

In 1947, the Italian Republic formally lost all her overseas colonial possessions as a result of the Treaty of Peace with Italy. There were discussions to maintain Tripolitania (a province of Italian Libya) as the last Italian colony, but these were not successful. In November 1949, Italian Somaliland was made a United Nations Trust Territory under Italian administration. This lasted until 1 July 1960, when Italian Somaliland was granted its independence and, together with British Somaliland, formed the Somali Republic.

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nigel Thomas. Armies in the Balkans 1914–18. Osprey Publishing, 2001, p. 17.

- ↑ Betts (1975), p.12

- ↑ Betts (1975), p.97

- ↑ Lowe, p.21

- ↑ Lowe, p.24

- ↑ Lowe, p.27

- ↑ Pakenham (1992), p.280

- ↑ Pakenham (1992), p.471

- ↑ Pakenham, p.281

- ↑ Killinger (2002), p.122

- ↑ Pakenham, p.470

- ↑ Killinger, p.122

- ↑ Pakenham (1992), p.7

- ↑ Map and information

- ↑ Killinger (2002), p.133

- ↑ Fry (2002), p.178

- ↑ Giuseppe Praga, Franco Luxardo. History of Dalmatia. Giardini, 1993. Pp. 281.

- 1 2 Paul O'Brien. Mussolini in the First World War: the Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist. Oxford, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Berg, 2005. Pp. 17.

- ↑ A. Rossi. The Rise of Italian Fascism: 1918–1922. New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2010. Pp. 47.

- ↑ Lowe, p.187

- ↑ Lowe, pp. 191–199

- 1 2 3 Smith, Dennis Mack (1981). Mussolini, p. 170. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London.

- 1 2 3 4 Salerno, Reynolds Mathewson (2002). Vital crossroads: Mediterranean origins of the Second World War, 1935–1940, pp. 105–106. Cornell University Press

- 1 2 Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries. A history of eastern Europe: crisis and change. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 1998. Pp. 467.

- ↑ Allan R. Millett, Williamson Murray. Military Effectiveness, Volume 2. New edition. New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2010. P. 184.

- 1 2 Burgwyn, James H. (1997). Italian foreign policy in the interwar period, 1918–1940, p. 68. Praeger Publishers.

- 1 2 Robert H. Whealey. Hitler And Spain: The Nazi Role In The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. Paperback edition. Lexington, Kentucky, USA: University Press of Kentucky, 2005. P. 11.

- ↑ Sebastian Balfour, Paul Preston. Spain and the Great Powers in the Twentieth Century. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 1999. P. 152.

- ↑ R. J. B. Bosworth. The Oxford handbook of fascism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009. Pp. 246.

- ↑ John J. Mearsheimer. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. W. W. Norton & Company, 2003.

- ↑ The Road to Oran: Anglo-Franch Naval Relations, September 1939 – July 1940. Pp. 24.

- 1 2 Reynolds Mathewson Salerno. Vital Crossroads: Mediterranean Origins of the Second World War, 1935–1940. Cornell University, 2002. p 82–83.

- 1 2 "French Army breaks a one-day strike and stands on guard against a land-hungry Italy", LIFE, 19 Dec 1938. Pp. 23.

- 1 2 Dickson (2001), pg. 69

- ↑ Time Magazine Aosta on Alag?

- ↑ Calvocoressi (1999) p.166

- 1 2 Santi Corvaja, Robert L. Miller. Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings. New York, New York, USA: Enigma Books, 2008. Pp. 132.

- ↑ Dickson (2001) p.100

- ↑ Dickson (2001) p.101

- ↑ Dickson (2001) p.103

- ↑ Jowett (2001) p.7

Bibliography

- Betts, Raymond (1975). The False Dawn: European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century. University of Minnesota.

- Barker, A. J. (1971). The Rape of Ethiopia. Ballantine Books.

- Bosworth, R. J. B. (2005). Mussolini's Italy: Life Under the Fascist Dictatorship, 1915–1945. Penguin Books.

- Calvocoressi, Peter (1999). The Penguin History of the Second World War. Penguin.

- Dickson, Keith (2001). World War II For Dummies. Wiley Publishing, INC.

- Fry, Michael (2002). Guide to International Relations and Diplomacy. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Howard, Michael (1998). The Oxford History of the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press.

- Jowett, Philip (1995). Axis Forces in Yugoslavia 1941–45. Osprey Publishing.

- Jowett, Philip (2001). The Italian Army 1940–45 (2): Africa 1940–43. Osprey Publishing.

- Killinger, Charles (2002). The History of Italy. Greenwood Press.

- Lowe, C.J. (2002). Italian Foreign Policy 1870–1940. Routledge.

- Mauri Arnaldo,(2004) Eritrea's early stages in monetary and banking development, "International Review of Economics", Vol. LI, n. 4, pp. 547–569.

- Maurizio Marinelli, Giovanni Andornino, Italy’s Encounter with Modern China: Imperial dreams, strategic ambitions, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Scramble for Africa: White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. New York: Perennial. ISBN 9780380719990.

- Patman, Robert G. (2009). The Soviet Union in the Horn of Africa: The Diplomacy of Intervention and Disengagement. Cambridge University Press.

External links

- (Italian) Atlas of Italian colonies, written by Baratta Mario and Visintin Luigi in 1928

.svg.png)