Gertrude Ederle

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Gertrude Caroline Ederle | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname(s) | "Trudy," "Gertie" | ||||||||||||||||||

| National team |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

October 23, 1905 Manhattan, New York City | ||||||||||||||||||

| Died |

November 30, 2003 (aged 98) Wyckoff, New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 141 lb (64 kg) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Swimming | ||||||||||||||||||

| Strokes | Freestyle | ||||||||||||||||||

| Club | Women's Swimming Association | ||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||

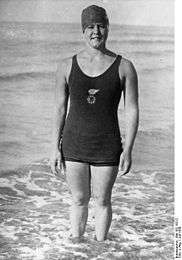

Gertrude Caroline Ederle (October 23, 1905 – November 30, 2003) was an American competition swimmer, Olympic champion, and former world record-holder in five events. On 6 August 1926, she became the first woman to swim across the English Channel. Among other nicknames, the press sometimes called her "Queen of the Waves."[1]

Early years

Gertrude Ederle was born on October 23, 1905 in Manhattan, New York City. Ederle, the third of six children, was born in New York City, the daughter of German immigrants, Gertrude Anna Haberstroh and Henry Ederle.[2][3] According to a biography of Ederle, America's Girl, her father ran a butcher shop on Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan. Her father taught her to swim in Highlands, New Jersey, where the family owned a summer cottage.

Amateur career

Ederle trained at the Women's Swimming Association (WSA), which produced such competitors as Ethelda Bleibtrey, Charlotte Boyle, Helen Wainwright, Aileen Riggin, Eleanor Holm and Esther Williams. Her yearly dues of $3 allowed Trudy to swim at the tiny Manhattan indoor pool. But, according to America's Girl, "the WSA was already the center of competitive swimming, a sport that was becoming increasingly popular with the evolution of a bathing suit that made it easier to get through the water." The director, Charlotte "Eppy" Epstein, had already urged the AAU to endorse women's swimming as a sport in 1917 and in 1919 pressured the AAU to "allow swimmers to remove their stockings for competition as long as they quickly put on a robe once they got out of the water."

That wasn't the only advantage of belonging to the WSA. The American crawl, a variation of the Australian crawl, was developed at the WSA by Louis Handley. According to America's Girl, "Handley thought the Australian crawl, in which swimmers did three kicks and then turned on their side to take a breath and do a scissors kick, could be improved ... The finished product – and its eight-beat variation, which Ederle would use – became the American crawl, and Handley was its proud father." Along with Handley, Epstein made New York female swimmers a force to be reckoned with. Ederle joined the club when she was only twelve. The same year set her first world record in the 880 yard freestyle, becoming the youngest world record holder in swimming. She set eight more world records after that, seven of them in 1922 at Brighton Beach.[4] In total, Ederle held 29 US national and world records from 1921 until 1925.[5]

At the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, Ederle won a gold medal as a member of the first-place U.S. team in the 4×100 meter freestyle relay. Together with her American relay teammates Euphrasia Donnelly, Ethel Lackie and Mariechen Wehselau, she set a new world record of 4:58.8 in the event final. Individually, she received bronze medals for finishing third in the women's 100-meter freestyle and women's 400-meter freestyle races.[4]

Trudy had been favored to win a gold in all three events and "would later say her failure to win three golds in the games was the biggest disappointment of her career." Still, she was proud to have been a part of the American team that brought home 99 medals from the Paris Olympics. It was an illustrious Olympic team – swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, oarsman Benjamin Spock, tennis player Helen Wills, and long-jumper DeHart Hubbard, who, according to America's Girl, was "the first black man to win an individual gold." The U.S. Olympic team had its own ticker-tape parade in 1924.

Professional career

In 1925, Ederle turned professional. The same year she swam the 22 miles from Battery Park to Sandy Hook in seven hours and 11 minutes, a record time which stood for 81 years before being broken by Australian swimmer Tammy van Wisse.[6] Ederle's nephew Bob later described his aunt's swim as a "midnight frolic" and a "warm-up" for her later swim across the English channel.[6]

The Women's Swimming Association sponsored Helen Wainwright and Trudy for an attempt at swimming the Channel. Helen Wainwright pulled out at the last minute because of an injury, but Trudy decided to go to France on her own. She trained with Jabez Wolffe, a swimmer who had attempted to swim the Channel 22 times. During the training, Wolffe continually tried to slow Trudy's pace, saying that she would never last at that speed. The training with Wolffe did not go well. In her first attempt at the Channel on August 18, 1925, Trudy was disqualified when Wolffe ordered another swimmer (who was keeping her company in the water), Ishak Helmy, to recover her from the water. According to Trudy and other witnesses, she was not "drowning" but resting, floating face-down. Trudy bitterly disagreed with Wolffe's decision.

Her successful Channel swim – this time training with coach Bill Burgess who had successfully swum the Channel in 1911 – began approximately one year later at Cape Gris-Nez in France at 07:08 on the morning of August 6, 1926. She came ashore at Kingsdown, Kent, 14 hours and 34 minutes later. Her record stood until Florence Chadwick swam the channel in 1950 in 13 hours and 20 minutes. Ederle used motorcycle goggles to protect her eyes from salty water, as did Burgess in 1911. However, while Burgess swam breaststroke, she used crawl, and therefore had her goggles sealed with paraffin to render them water tight.[7]

Gertrude possessed a contract from both the New York Daily News and Chicago Tribune when she attempted the Channel swim a second time. The money she received paid her expenses and provided her with a modest salary. It also gave her a bonus in exchange for exclusive rights to her personal story. The Daily News and the Chicago Tribune got the jump on every other newspaper in America.

Another American swimmer in France in 1926 to try and swim the Channel was Lillian Cannon from Baltimore. She was also sponsored by a newspaper, the Baltimore Post, which tried to create a rivalry between her and Ederle in the weeks spent training off the French coast. In addition to Cannon, several other swimmers, including two other American women – Clarabelle Barrett and Amelia Gade Corson – were training in England with the goal of becoming the first woman to swim the Channel. Barrett and Cannon were unsuccessful but three weeks after Ederle's feat, Corson crossed in a time that was 50 minutes slower than Ederle.

For her second attempt at the Channel, Ederle had an entourage aboard the tug (the Alsace) on August 6, 1926, which included her father and one of her sisters, Meg, as well as Julia Harpman, wife of Westbrook Pegler and a writer for the New York Daily News, the paper that sponsored Ederle's swim. Harpman wouldn't allow reporters from other newspapers on the tug – in order to protect her "scoop" – and as a result a second tug was hired by the disgruntled reporters. On several occasions during the swim this tug (the Morinie) came in close to Ederle and nearly endangered her chances. The incident caused subsequent bitterness. It also led to accusations in the British press that the two tugs had in fact sheltered Ederle from the bad weather and thus made her swim "easier".

During her twelfth hour at sea, Burgess, her trainer, had become so concerned by unfavorable winds that he called to her 'Gertie, you must come out!' The swimmer lifted her head from the choppy waters and replied, 'What for?'

Only five men had been able to swim the English Channel before Ederle. The best time had been 16 hours, 33 minutes by Enrique Tiraboschi. Ederle walked up the beach at Kingsdown, England after 14 hours and 34 minutes. The first person to greet her was a British immigration officer who requested a passport from "the bleary-eyed, waterlogged teenager." (She was actually 20, not "a teenager," when she successfully swam the Channel.)

When Ederle returned home, she was greeted with a ticker-tape parade in New York City. More than two million people lined the streets of New York to cheer her. Subsequently she went on to play herself in a movie (Swim Girl, Swim starring Bebe Daniels) and tour the vaudeville circuit, including later Billy Rose's Aquacade. She met President Coolidge and had a song and a dance step named for her. Her manager, Dudley Field Malone, was not able to capitalize on her notoriety, so Ederle's career in vaudeville wasn't a huge financial success. The Great Depression also diminished her financial rewards. A fall down the steps of her apartment building in 1933 twisted her spine and left her bedridden for several years, but she recovered well enough to appear at the 1939 New York World's Fair.

Death

She had poor hearing since childhood due to measles, and by the 1940s she was almost completely deaf. Aside from her time in Vaudeville, Trudy taught swimming to deaf children.[4] She never married and died on November 30, 2003, in Wyckoff, New Jersey, at the age of 98.[1] She was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Legacy

Ederle was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame as an "Honor Swimmer" in 1965.[5]

She is mentioned in Episode 11 of the first season of Barney Miller by the Bird Man character Roland Gusik, as being one who lived her dreams, and did not allow them to be stopped.

An annual swim from New York City's Battery Park to Sandy Hook, New Jersey is called the Ederle Swim in memory of Gertrude Ederle, and follows the course she swam.[8][9]

The Gertrude Ederle Recreation Center is located in Manhattan.[10]

A BBC Radio 4 play, The Great Swim, by Anita Sullivan, based on the 2008 book of the same name by Gavin Mortimer, was first broadcast on September 1, 2010, and repeated on January 23, 2012. It dramatises Ederle's record-breaking crossing of the English Channel.[11]

Her name makes a cameo appearance in Disney's The Princess and the Frog in a newspaper article being read by character Eli "Big Daddy" La Bouff.

See also

- List of female adventurers

- List of Olympic medalists in swimming (women)

- World record progression 100 metres freestyle

- World record progression 200 metres freestyle

- World record progression 400 metres freestyle

- World record progression 800 metres freestyle

- World record progression 4 × 100 metres freestyle relay

References

- 1 2 Severo, Richard (December 1, 2003). "Gertrude Ederle, the First Woman to Swim Across the English Channel, Dies at 98". New York Times. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

Gertrude Ederle, who was called America's best girl by President Calvin Coolidge in 1926 after she became the first woman to swim across the English Channel. She was 98 when she passed away.

- ↑ http://www.encyclopedia.com/article-1G2-2875000093/ederle-gertrude-caroline-trudy.html

- ↑ Gertrude Ederle becomes first woman to swim English Channel. History.com. Retrieved on May 20, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Sports-Reference.com, Olympic Sports, Athletes, Trudy Ederle. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- 1 2 International Swimming Hall of Fame, Honorees, Gertrude Ederle (USA). Retrieved on March 16, 2015.

- 1 2 The Two River Times. Trtnj.com. Retrieved on May 20, 2014.

- ↑ The history of goggles. International Swimming Hall of Fame

- ↑ Swimmers Brave Chill For NY-NJ Course « CBS New York. Newyork.cbslocal.com (October 24, 2010). Retrieved on May 20, 2014.

- ↑ Girls swimming: Charlotte Samuels of Ridgewood featured in 'Faces in the Crowd' – NJ.com. Highschoolsports.nj.com. Retrieved on May 20, 2014.

- ↑ Gertrude Ederle Recreation Center : NYC Parks. Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved on May 20, 2014.

- ↑ BBC Radio 4 – Afternoon Drama, The Great Swim. Bbc.co.uk (January 23, 2012). Retrieved on May 20, 2014.

Further reading

- Dahlberg, Tim, Mary Ederle Ward and Brenda Greene, America's Girl (2009), St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-38265-0.

- Mortimer, Gavin, The Great Swim (2008) Walker and Co, ISBN 0-8027-1595-8.

- Stout, Glenn. Young Woman and the Sea: How Trudy Ederle Conquered the English Channel and Inspired the World (2009), Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0-618-85868-7. A full biography of Ederle.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gertrude Ederle. |

- N.Y. Times Obituary for Gertrude Ederle

- Gertrude Ederle – profile at Find A Grave

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ethelda Bleibtrey |

Women's 100-meter freestyle world record-holder (long course) June 30, 1923 – July 19, 1924 |

Succeeded by Mariechen Wehselau |