Lake Superior

Lake Superior (French: Lac Supérieur) is the largest of the Great Lakes of North America. The lake is shared by the Canadian province of Ontario to the north, the US state of Minnesota to the west, and Wisconsin and Michigan to the south. It is generally considered the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface area. It is the world's third-largest freshwater lake by volume and the largest by volume in North America.[6]

Name

The Ojibwe call the lake gichi-gami (pronounced as gitchi-gami and kitchi-gami in other dialects),[7] meaning "be a great sea." Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote the name as "Gitche Gumee" in The Song of Hiawatha, as did Gordon Lightfoot in his song, "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald". According to other sources the actual Ojibwe name is Ojibwe Gichigami ("Ojibwe's Great Sea") or Anishinaabe Gichigami ("Anishinaabe's Great Sea").[8] The 1878 dictionary by Father Frederic Baraga, the first one written for the Ojibway language, gives the Ojibwe name as Otchipwe-kitchi-gami (reflecting Ojibwe Gichigami).[7] The first French explorers approaching the great inland sea by way of the Ottawa River and Lake Huron during the 17th century referred to their discovery as le lac supérieur. Properly translated, the expression means "Upper Lake," that is, the lake above Lake Huron. The lake was also called Lac Tracy (named for Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy) by 17th century Jesuit missionaries.[9] The British, upon taking control of the region from the French in the 1760s following the French and Indian War, anglicized the lake's name to Superior, "on account of its being superior in magnitude to any of the lakes on that vast continent."[10]

Hydrography

Lake Superior empties into Lake Huron via the St. Marys River and the Soo Locks. Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake in the world in area (if Lakes Michigan and Huron are taken separately; see Lake Michigan–Huron), and the third largest in volume, behind Lake Baikal in Siberia and Lake Tanganyika in East Africa. The Caspian Sea, while larger than Lake Superior in both surface area and volume, is brackish; though presently isolated, prehistorically the Caspian has been repeatedly connected to and isolated from the Mediterranean via the Black Sea.

Lake Superior has a surface area of 31,700 square miles (82,103 km2),[1] which is approximately the size of South Carolina or Austria. It has a maximum length of 350 statute miles (560 km; 300 nmi) and maximum breadth of 160 statute miles (257 km; 139 nmi).[2] Its average depth is 80.5 fathoms (483 ft; 147 m) with a maximum depth of 222.17 fathoms (1,333 ft; 406 m).[1][2][3] Lake Superior contains 2,900 cubic miles (12,100 km³) of water.[1] There is enough water in Lake Superior to cover the entire land mass of North and South America to a depth of 30 centimetres (12 in).[17] The shoreline of the lake stretches 2,726 miles (4,387 km) (including islands).[1]

American limnologist J. Val Klump was the first person to reach the lowest depth of Lake Superior on July 30, 1985, as part of a scientific expedition, which at 122 fathoms 1 foot (733 ft or 223 m) below sea level is the lowest spot in the continental interior of the United States and the second-lowest spot in the interior of the North American continent after the deeper Great Slave Lake in Canada (1,503 feet [458 m] below sea level). (Though Crater Lake is the deepest lake in the United States and deeper than Lake Superior, Crater Lake's elevation is higher and consequently its deepest point is 4,229 feet (1,289 m) above sea level.)

While the temperature of the surface of Lake Superior varies seasonally, the temperature below 110 fathoms (660 ft; 200 m) is an almost constant 39 °F (4 °C). This variation in temperature makes the lake seasonally stratigraphic. Twice per year, however, the water column reaches a uniform temperature of 39 °F (4 °C) from top to bottom, and the lake waters thoroughly mix. This feature makes the lake dimictic. Because of its volume, Lake Superior has a retention time of 191 years.[18][19]

Annual storms on Lake Superior regularly feature wave heights of over 20 feet (6 m).[20] Waves well over 30 feet (9 m) have been recorded.[21]

Tributaries and outlet

The lake is fed by over 200 rivers. The largest include the Nipigon River, the St. Louis River, the Pigeon River, the Pic River, the White River, the Michipicoten River, the Bois Brule River and the Kaministiquia River. Lake Superior drains into Lake Huron via the St. Marys River. There are rapids at the river's upper (Lake Superior) end where the river bed has a relatively steep gradient. The Soo Locks were built to enable ships to bypass the rapids and to overcome the 25-foot (8 m) height difference between Lakes Superior and Huron.

Water levels

The lake's average surface elevation is 600 feet (183 m)[2][18] above sea level. Until approximately 1887 the natural hydraulic conveyance through the St. Marys River rapids determined outflow from Lake Superior. By 1921 development in support of transportation and hydroelectric power resulted in gates, locks, power canals and other control structures completely spanning St. Marys rapids. The regulating structure is known as the Compensating Works and is operated according to a regulation plan known as Plan 1977-A. Water levels, including diversions of water from the Hudson Bay watershed, are regulated by the International Lake Superior Board of Control which was established in 1914 by the International Joint Commission.

Lake Superior's water level was at a new record low in September 2007, slightly less than the previous record low in 1926.[22] However, the water levels returned within a few days.[23]

Historic high water The lake's water level fluctuates from month to month, with the highest lake levels in October and November. The normal high-water mark is 1.17 feet (0.36 m) above datum (601.1 ft or 183.2 m). In the summer of 1985, Lake Superior reached its highest recorded level at 2.33 feet (0.71 m) above datum.[24] The winter of 1986 set new high-water records through the winter and spring months (January to June), ranging from 1.33 feet (0.41 m) to 1.833 feet (0.559 m) above Chart Datum.[24]

Historic low water The lake's lowest levels occur in March and April. The normal low-water mark is 0.33 feet (0.10 m) below datum (601.1 ft or 183.2 m). In the winter of 1926 Lake Superior reached its lowest recorded level at 1.58 feet (0.48 m) below datum.[24] Additionally, the entire first half of the year (January to June) included record low months. The low water was a continuation of the dropping lake levels from the previous year, 1925, which set low-water records for October through December. During the nine-month period October 1925 to June 1926 water levels ranged from 1.58 feet (0.48 m) to 0.33 feet (0.10 m) below Chart Datum.[24] In the summer of 2007 monthly historic lows were set; August at 0.66 feet (0.20 m), September at 0.58 feet (0.18 m).[24]

Climate change

According to a study by professors at the University of Minnesota Duluth, Lake Superior may have warmed faster than its surrounding area.[25] Summer surface temperatures in the lake appeared to have increased by about 4.5 °F (2.5 °C) since 1979, compared with an approximately 2.7 °F (1.5 °C) increase in the surrounding average air temperature. The increase in the lake's surface temperature may be related to the decreasing ice cover. Less winter ice cover allows more solar radiation to penetrate and warm the water. If trends continue, Lake Superior, which freezes over completely once every 20 years, could routinely be ice-free by 2040.[26] This would be a significant departure from historical records as, according to Hubert Lamb, Samuel Champlain reported ice along the shores of Lake Superior in June 1608.[27] Warmer temperatures could actually lead to more snow in the lake effect snow belts along the shores of the lake, especially in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. However, 2 recent consecutive winters (2013–2014 and 2014–2015) brought unusually high ice coverage to the Great Lakes, and on March 6, 2014 overall ice coverage peaked at 92.5%, the second-highest in recorded history.[28]

Geography

The largest island in Lake Superior is Isle Royale in the state of Michigan. Isle Royale contains several lakes, some of which also contain islands. Other large famous islands include Madeline Island in the state of Wisconsin, Michipicoten Island in the province of Ontario, and Grand Island (the location of the Grand Island National Recreation Area) in the state of Michigan.

The larger cities on Lake Superior include: the twin ports of Duluth, Minnesota, and Superior, Wisconsin; Thunder Bay, Ontario; Marquette, Michigan; and the twin cities of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. Duluth, at the western tip of Lake Superior, is the most inland point on the St. Lawrence Seaway and the most inland port in the world.

Among the scenic places on the lake are: the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, Isle Royale National Park, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Pukaskwa National Park, Lake Superior Provincial Park, Grand Island National Recreation Area, Sleeping Giant (Ontario) and Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore.

Great Lakes Circle Tour

The Great Lakes Circle Tour is a designated scenic road system connecting all of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River.[29]

Climate

Lake Superior's size reduces the severity of the seasons of its humid continental climate (more typically seen in locations like Nova Scotia).[30] The water surface's slow reaction to temperature changes, seasonally ranging between 32 and 55 °F (0–13 °C) around 1970,[31] helps to moderate surrounding air temperatures in the summer and winter, and creates lake effect snow in colder months. The hills and mountains that border the lake hold moisture and fog, particularly in the fall.

The lake's surface temperature has risen by 4.5 °F (2.5 °C) since 1979.[32]

Geology

The rocks of Lake Superior's northern shore date back to the early history of the earth. During the Precambrian (between 4.5 billion and 540 million years ago) magma forcing its way to the surface created the intrusive granites of the Canadian Shield.[33] These ancient granites can be seen on the North Shore today. It was during the Penokean orogeny, part of the process that created the Great Lakes Tectonic Zone, that many valuable metals were deposited. The region surrounding the lake has proved to be rich in minerals. Copper, iron, silver, gold and nickel are or were the most frequently mined. Examples include the Hemlo gold mine near Marathon, copper at Point Mamainse, silver at Silver Islet and uranium at Theano Point.

The mountains steadily eroded, depositing layers of sediments that compacted and became limestone, dolostone, taconite and the shale at Kakabeka Falls.

The continent was later riven, creating one of the deepest rifts in the world.[34] The lake lies in this long-extinct Mesoproterozoic rift valley, the Midcontinent Rift. Magma was injected between layers of sedimentary rock, forming diabase sills. This hard diabase protects the layers of sedimentary rock below, forming the flat-topped mesas in the Thunder Bay area.

Amethyst formed in some of the cavities created by the Midcontinent Rift and there are several amethyst mines in the Thunder Bay area.[35]

Lava erupted from the rift and formed the black basalt rock of Michipicoten Island, Black Bay Peninsula, and St. Ignace Island.

During the Wisconsin glaciation 10,000 years ago, ice covered the region at a thickness of 1.25 miles (2 km). The land contours familiar today were carved by the advance and retreat of the ice sheet. The retreat left gravel, sand, clay and boulder deposits. Glacial meltwaters gathered in the Superior basin creating Lake Minong, a precursor to Lake Superior.[36] Without the immense weight of the ice, the land rebounded, and a drainage outlet formed at Sault Ste. Marie, which would become known as St. Mary's River.

History

The first people came to the Lake Superior region 10,000 years ago after the retreat of the glaciers in the last Ice Age. They are known as the Plano, and they used stone-tipped spears to hunt caribou on the northwestern side of Lake Minong.

The next documented people were known as the Shield Archaic (c. 5000–500 BC). Evidence of this culture can be found at the eastern and western ends of the Canadian shore. They used bows and arrows, dugout canoes, fished, hunted, mined copper for tools and weapons, and established trading networks. They are believed to be the direct ancestors of the Ojibwe and Cree.[37]

The Laurel people (c. 500 BC to AD 500) developed seine net fishing, evidence being found at rivers around Superior such as the Pic and Michipicoten.

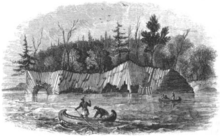

Another culture known as the Terminal Woodland Indians (c. AD 900–1650) has been found. They were Algonkian people who hunted, fished and gathered berries. They used snow shoes, birch bark canoes and conical or domed lodges. At the mouth of the Michipicoten River, nine layers of encampments have been discovered. Most of the Pukaskwa Pits were likely made during this time.[37]

The Anishinaabe, which includes the Ojibwe or Chippewa, have inhabited the Lake Superior region for over five hundred years and were preceded by the Dakota, Fox, Menominee, Nipigon, Noquet and Gros Ventres. They called Lake Superior either Ojibwe Gichigami ("the Ojibwe's Great Sea") or Anishnaabe Gichgamiing ("the Anishinaabe's Great Sea"). After the arrival of Europeans, the Anishinaabe made themselves the middle-men between the French fur traders and other Native peoples. They soon became the dominant Indian nation in the region: they forced out the Sioux and Fox and won a victory against the Iroquois west of Sault Ste. Marie in 1662. By the mid-18th century, the Ojibwe occupied all of Lake Superior's shores.[38]

In the 18th century, the fur trade in the region was booming, with the Hudson's Bay Company having a virtual monopoly. In 1783, however, the North West Company was formed to rival the Hudson's Bay Company. The North West Company built forts on Lake Superior at Grand Portage, Fort William, Nipigon, the Pic River, the Michipicoten River, and Sault Ste. Marie. But by 1821, with competition taking too great a toll on both, the companies merged under the Hudson's Bay Company name.

Many towns around the lake are either current or former mining areas, or engaged in processing or shipping. Today, tourism is another significant industry; the sparsely populated Lake Superior country, with its rugged shorelines and wilderness, attracts tourists and adventurers.

Shipping

Lake Superior has been an important link in the Great Lakes Waterway, providing a route for the transportation of iron ore as well as grain and other mined and manufactured materials. Large cargo vessels called lake freighters, as well as smaller ocean-going freighters, transport these commodities across Lake Superior.

Because of ice, the Lake is closed to shipping from mid-January to late March. Exact dates for the shipping season vary each year,[39] depending on weather conditions that form and break the ice.

Shipwrecks

According to shipwreck historian Frederick Stonehouse, the southern shore of Lake Superior between Grand Marais, Michigan, and Whitefish Point is known as the "Graveyard of the Great Lakes" and more ships have been lost around the Whitefish Point area than any other part of Lake Superior.[40] These shipwrecks are now protected by the Whitefish Point Underwater Preserve.

Storms that claimed multiple ships include the Mataafa Storm in 1905 and the Great Lakes Storm of 1913.

Wreckage of SS Cyprus – a 420-foot (130 m) ore carrier that sank on October 11, 1907, during a Lake Superior storm in 77 fathoms (460 ft or 140 m) of water – was located in August 2007. All but Charles G. Pitz of Cyprus's 23 crew perished . The ore carrier sank in Lake Superior on her second voyage, while hauling iron ore from Superior, Wisconsin, to Buffalo, New York. Built in Lorain, Ohio, Cyprus was launched August 17, 1907.[41]

In 1918 the last warships to sink in the Great Lakes, French minesweepers Inkerman and Cerisoles, vanished in a Lake Superior storm. With 78 crewmembers dead, their sinking marked the largest loss of life on Lake Superior to date.

SS Edmund Fitzgerald was the last major shipwreck on Lake Superior, sinking 15 nautical miles (28 km; 17 mi) from Whitefish Point in a storm on November 10, 1975. The wreck was immortalized by Gordon Lightfoot in his ballad "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald". All 29 crew members perished when the ship sank, and no bodies were ever recovered. Edmund Fitzgerald was swallowed up so intensely by Lake Superior that the 729-foot (222 m) ship split in half; her two pieces are approximately 170 feet (52 m) apart in a depth of 91 fathoms 4 feet (550 ft or 170 m).

According to legend, "Lake Superior seldom gives up her dead".[42] This is because of the unusually low temperature of the water, estimated at under 36 °F (2 °C) on average around 1970.[31] Normally, bacteria feeding on a sunken decaying body will generate gas inside the body, causing it to float to the surface after a few days. However, Lake Superior's water is cold enough year-round to inhibit bacterial growth, and bodies tend to sink and never resurface.[43] This is alluded to in Lightfoot's "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald" ballad. Fitzgerald adventurer Joe MacInnis reported that, in July 1994, explorer Frederick Shannon's Expedition 94 to the wreck of Edmund Fitzgerald discovered and filmed a man's body near the port side of her pilothouse, not far from the open door, "fully clothed, wearing an orange life jacket, and lying face down in the sediment."[44]

Ecology

Over 80 species of fish have been found in Lake Superior. Species native to the lake include: banded killifish, bloater, brook trout, burbot, cisco, lake sturgeon, lake trout, lake whitefish, longnose sucker, muskellunge, northern pike, pumpkinseed, rock bass, round whitefish, smallmouth bass, walleye, white sucker and yellow perch. In addition, many fish species have been either intentionally or accidentally introduced to Lake Superior: Atlantic salmon, brown trout, carp, chinook salmon, coho salmon, freshwater drum, pink salmon, rainbow smelt, rainbow trout, round goby, ruffe, sea lamprey and white perch.[45][46]

Lake Superior has fewer dissolved nutrients relative to its water volume than the other Great Lakes and so is less productive in terms of fish populations and is an oligotrophic lake. This is a result of the underdeveloped soils found in its relatively small watershed.[18] However, nitrate concentrations in the lake have been continuously rising for more than a century. They are still much lower than levels considered dangerous to human health; but this steady, long-term rise is an unusual record of environmental nitrogen buildup. It may relate to anthropogenic alternations to the regional nitrogen cycle, but researchers are still unsure of the causes of this change to the lake's ecology.[47]

As for other Great Lakes fish, populations have also been affected by the accidental or intentional introduction of foreign species such as the sea lamprey and Eurasian ruffe. Accidental introductions have occurred in part by the removal of natural barriers to navigation between the Great Lakes. Overfishing has also been a factor in the decline of fish populations.[6]

See also

- North Shore of Lake Superior

- South Shore of Lake Superior

General

- Great Lakes

- Great Lakes Areas of Concern

- Great Lakes census statistical areas

- Great Lakes Commission

- Great Recycling and Northern Development Canal

- Great Storm of 1913

- International Boundary Waters Treaty

- List of cities along the Great Lakes

- Seiche

- Shipwrecks of the 1913 Great Lakes storm

- Sixty Years' War for control of the Great Lakes

- Third Coast

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Great Lakes: Basic Information: Physical Facts". U.S. Government. May 25, 2011. Archived from the original on October 29, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Great Lakes Atlas: Factsheet #1". United States Environmental Protection Agency. April 11, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- 1 2 Wright, John W., ed. (2006). The New York Times Almanac (2007 ed.). New York, New York: Penguin Books. p. 64. ISBN 0-14-303820-6.

- ↑ Shorelines of the Great Lakes Archived April 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Great Lakes Water Levels, published by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The link also has daily elevations for the current month.

- 1 2 Superior Pursuit: Facts About the Greatest Great Lake – Minnesota Sea Grant University of Minnesota. Retrieved on August 9, 2007.

- 1 2 Kitchi-Gami Almanac – The Name. lakesuperior.com. January 1, 2006

- ↑ Under the Shadow of the Gods: A guide to the History of the Canadian Shore of Lake Superior by Barbara Chisholm & Andrea Gutsche 1st edition 1998 printed bound in Canada by Transcontinental Printing Inc

- ↑ Great Lakes Atlas, Environment Canada and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1995.

- ↑ George R. Stewart, "Names on the Land, A historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States," 1945, p. 83

- 1 2 National Geophysical Data Center, 1999. Bathymetry of Lake Superior. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. [access date: 2015-03-23].

(the general reference to NGDC because this lake was never published, compilation of Great Lakes Bathymetry at NGDC has been suspended). - ↑ National Geophysical Data Center, 1999. Bathymetry of Lake Huron. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V5G15XS5 [access date: March 23, 2015]. (only small portion of this map)

- ↑ National Geophysical Data Center, 1999. Global Land One-kilometer Base Elevation (GLOBE) v.1. Hastings, D. and P.K. Dunbar. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V52R3PMS [access date: March 16, 2015].

- 1 2 "About Our Great Lakes: Tour". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL). Retrieved April 2, 2015. Google Earth Great Lakes Tour GreatLakesTour_Merged.kmz

- ↑ Wright Jr., H. E. (1973). Black, Robert Foster; Goldthwait, Richard Parker; Willman, Harold, eds. "Tunnel Valleys, Glacial Surges, and Subglacial Hydrology of the Superior Lobe, Minnesota". Geological Society of America Memoirs. Geological Society of America Memoirs. Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America Inc. 136: 251–276. doi:10.1130/MEM136-p251. ISBN 0813711363. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Regis, Robert S., Jennings-Patterson, Carrie, Wattrus, Nigel, and Rausch, Deborah, Relationship of deep troughs in the eastern Lake Superior basin and large-scale glaciofluvial landforms in the central upper peninsula of Michigan. The Geological Society of America. North-Central Section – 37th Annual Meeting (March 24–25, 2003) Kansas City, Missouri. Paper No. 19-10.

- ↑ North America (2.47×107 km²) and South America (1.78×107 km²) combined cover 4.26×107 km². Lake Superior's volume (1.20×104 km³) over 4.26×107 km² gives a depth of 0.282 m.

- 1 2 3 "Lake Superior". Minnesota Sea Grant, University of Minnesota. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ↑ Lake Superior's Natural Processes | Minnesota Sea Grant. Seagrant.umn.edu (October 15, 2014). Retrieved on 2015-11-17.

- ↑ "The fall storm season." (Website.) National Weather Service, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved on September 25, 2007

- ↑ Chisholm, B. & Gutsche, p. xiii

- ↑ Associated Press. (October 1, 2007.) "Lake Superior hits record lows." The Globe and Mail, via globeandmail.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-06. Archived June 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Current Great Lakes Water Levels. Great Lakes Information Network. Retrieved on October 23, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Monthly bulletin of Lake Levels for The Great Lakes; September 2009; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Detroit District

- ↑ Marshall, Jessica. (May 30, 2007.) "Global warming is shrinking the Great Lakes." New Scientist, via newscientist.com. Retrieved on 2007-09-25. Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Associated Press. (June 4, 2007.) "Lake Superior warming faster than surrounding climate." The Globe and Mail, via globeandmail.com (fee required). Retrieved on 2007-09-25. Archived April 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lamb, Hubert H. (1995). "The little ice age". Climate, history and the modern world. London: Routledge. p. 241. ISBN 0-415-12734-3.

- ↑ Extensive Great Lakes Ice Coverage to Limit Severe Weather, Pose Challenges to Shipping Industry. Accuweather.com. Retrieved on November 17, 2015.

- ↑ Great Lakes Circle Tour. Great-lakes.net. Retrieved on November 17, 2015.

- ↑ Highway 17: A Scenic Route along the northern Lake Superior shore. Thekingshighway.ca (February 18, 2012). Retrieved on 2015-11-17.

- 1 2 Derecki, J. A. (July 1980.) "NOAA Technical Memorandum ERL GLERL-29: Evaporation from Lake Superior." Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, page 37. Retrieved on September 25, 2007.

- ↑ "Global warming is shrinking the Great Lakes." New Scientist, via newscientist.com. Retrieved on September 25, 2007. Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Geology of National Parks, Second Edition, Ann G. Harris, Kendall Hunt Publishing, Dubuque, Iowa, 1977, p. 200

- ↑ Linder, Douglas O. (2006) ''Simply Superior: The World's Greatest Lake'' "Lake Superior facts". Law.umkc.edu. Retrieved on November 17, 2015.

- ↑ Ontario Amethyst: Ontario's Mineral Emblem Ontario Ministry of Northern Development and Mines. Retrieved on August 4, 2007.

- ↑ Chisholm & Gutsche, p. xv

- 1 2 Chisholm & Gutsche, p. xvi

- ↑ Chisholm & Gutsche, p. xvii

- ↑ "Paul R. Treggurtha: Last trip for the Tregurtha this year". Duluth Shipping News. January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

Another trip here was planned but has apparently been canceled, making this her last and 41st visit this season. Last year, without a late start due to ice, the Tregurtha was here 49 times.

- ↑ Stonehouse, Frederick (1985, 1998). Lake Superior's Shipwreck Coast, p. 267, Avery Color Studios, Gwinn, Michigan, U.S.A. ISBN 0-932212-43-3,

- ↑ "Century-old shipwreck discovered: Ore carrier went down in Lake Superior on its second voyage". Traverse City, Michigan: MSNBC. Associated Press. September 10, 2007.

- ↑ Kohl, Cris (1998). The 100 Best Great Lakes Shipwrecks, Volume II, p. 430. Seawolf Communications, Inc. ISBN 0-9681437-3-3.

- ↑ Chisholm & Gutsche, p. xxxiv

- ↑ MacInnis, Joseph (1998). Fitzgerald's Storm: The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Berkely, CA, USA: Thunder Bay Press. p. 101. ISBN 1-882376-53-6.

- ↑ "Lake Superior Fish Species". Minnesota Sea Grant, University of Minnesota. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ↑ Minnesota 2009 fishing regulations, p. 23

- ↑ Sterner, Robert W.; Anagnostou, Eleni; Brovold, Sandra; Bullerjahn, George S.; Finlay, Jacques C.; Kumar, Sanjeev; McKay, R. Michael L.; Sherrell, Robert M. (2007). "Increasing stoichiometric imbalance in North America's largest lake: Nitrification in Lake Superior". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (10): L10406. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3410406S. doi:10.1029/2006GL028861.

Bibliography

- Chisholm, B. & Gutsche, A., Superior: Under the Shadow of the Gods, Lynx Images, 1998 ISBN 0-9698427-7-5

Further reading

- Burt, Williams A., and Hubbard, Bela Reports on the Mineral Region of Lake Superior (Buffalo: L. Danforth, 1846), 113 pages.

- Grady, Wayne. The Great Lakes: The Natural History of a Changing Region.Greystone Books, D&M Publishers INC, 2007

- Hyde, Charles K., and Ann and John Mahan. The Northern Lights: Lighthouses of the Upper Great Lakes. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8143-2554-8 ISBN 9780814325544.

- Oleszewski, Wes, Great Lakes Lighthouses, American and Canadian: A Comprehensive Directory/Guide to Great Lakes Lighthouses, (Gwinn, Michigan: Avery Color Studios, Inc., 1998) ISBN 0-932212-98-0.

- Penrod, John, Lighthouses of Michigan, (Berrien Center, Michigan: Penrod/Hiawatha, 1998) ISBN 978-0-942618-78-5 ISBN 9781893624238

- Penrose, Laurie and Bill, A Traveler's Guide to 116 Michigan Lighthouses (Petoskey, Michigan: Friede Publications, 1999). ISBN 0-923756-03-5 ISBN 9780923756031

- Sims, P.K. and L.M.H. Carter, eds. Archean and Proterozoic Geology of the Lake Superior Region, U.S.A., 1993 [U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1556]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, 1996.

- Splake, T. Kilgore. Superior Land Lights. Battle Creek, MI: Angst Productions, 1984

- Stonehouse, Frederick. Marquette Shipwrecks. Marquette, MI: Harboridge Press, 1974

- Wagner, John L., Michigan Lighthouses: An Aerial Photographic Perspective, (East Lansing, Michigan: John L. Wagner, 1998) ISBN 1-880311-01-1 ISBN 9781880311011

- Wright, Larry and Wright, Patricia, Great Lakes Lighthouses Encyclopedia Hardback (Erin: Boston Mills Press, 2006) ISBN 1-55046-399-3

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. "[ Record Low Water Levels Expected on Lake Superior]." August 2007

- Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. "Great Lakes Sensitivity to Climatic Forcing: Hydrological Models." NOAA, 2006

- Shipwrecks

- "America"; Houghton, Michigan; Houghton Mining Gazette; Vol. 29; June 8, 1928

- Stonehouse, Frederick; Isle Royale Shipwrecks; Marquette, Michigan; Arery Color Studios; 1977

- "Cumberland" & "Wreck of Sidewheel Steamer Cumberland"; Detroit, Michigan; Detroit Free Press; January 29, 1974

- "S.S.George M. Cox Wrecked"; Houghton, Michigan; Houghton Mining Gazette; May 28, 1933

- Holdon, Thom "Reef of the Three C's"; Duluth, Minnesota; Lake Superior Marine Museum; Vol. 2, #4; July/August 1977

- Holdon, Thom; "Above and Below: Steamer America"; Duluth, Minnesota; Lake Superior Marine Museum; Vol. 3, #3 & #4; May/June & July/August 1978

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Superior. |

-

Geographic data related to Lake Superior at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Lake Superior at OpenStreetMap - Lake Superior NOAA nautical chart #14961 online

- International Lake Superior Board of Control

- EPA's Great Lakes Atlas

- EPA's Great Lakes Atlas Factsheet #1

- Great Lakes Coast Watch

- Parks Canada Lake Superior

- Minnesota Sea Grant – Lake Superior Page

- Lake Superior Bathymetry