Beryllium oxide

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Beryllium(II) monoxide | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Oxoberyllium | |

| Other names

Beryllia, Bromellete, Thermalox, Natural bromellite, Thermalox 995.[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

| 1304-56-9 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image Interactive image |

| 3902801 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:62842 |

| ChemSpider | 14092 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.758 |

| EC Number | 215-133-1 |

| MeSH | beryllium+oxide |

| PubChem | 14775 |

| RTECS number | DS4025000 |

| UN number | 1566 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| BeO | |

| Molar mass | 25.01 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colourless, vitreous crystals |

| Odor | Odourless |

| Density | 3.01 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | 2,507 °C (4,545 °F; 2,780 K) |

| Boiling point | 3,900 °C (7,050 °F; 4,170 K) |

| 0.00002 g/100 mL | |

| Band gap | 10.6 eV |

| Thermal conductivity | 330 W K−1 m−1 |

| Refractive index (nD) |

1.719 |

| Structure | |

| Hexagonal | |

| P63mc | |

| C6v | |

| Tetragonal | |

| Linear | |

| Thermochemistry | |

| 25.5 J/mol K | |

| Std molar entropy (S |

13.73–13.81 J K−1 mol−1 |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH |

−599 kJ/mol[2] |

| Gibbs free energy (ΔfG˚) |

−582 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | See: data page |

| GHS pictograms |   |

| GHS signal word | DANGER |

| H301, H315, H317, H319, H330, H335, H350, H372 | |

| P201, P260, P280, P284, P301+310, P305+351+338 | |

| EU classification (DSD) |

|

| R-phrases | R49, R25, R26, R36/37/38, R43, R48/23 |

| S-phrases | S53, S45 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LD50 (median dose) |

2062 mg kg−1 (mouse, oral) |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

| PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 0.002 mg/m3 C 0.005 mg/m3 (30 minutes), with a maximum peak of 0.025 mg/m3 (as Be)[3] |

| REL (Recommended) |

Ca C 0.0005 mg/m3 (as Be)[3] |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) |

Ca [4 mg/m3 (as Be)][3] |

| Related compounds | |

| Other anions |

Beryllium telluride |

| Other cations |

|

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

| Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Beryllium oxide (BeO), also known as beryllia, is an inorganic compound with the formula BeO. This colourless solid is a notable electrical insulator with a higher thermal conductivity than any other non-metal except diamond, and exceeds that of most metals.[4] As an amorphous solid, beryllium oxide is white. Its high melting point leads to its use as a refractory.[5] It occurs in nature as the mineral bromellite. Historically and in materials science, beryllium oxide was called glucina or glucinium oxide. Formation of BeO from beryllium and oxygen releases the highest energy per mass of reactants for any chemical reaction, close to 24 MJ/kg.

Preparation and chemical properties

Beryllium oxide can be prepared by calcining (roasting) beryllium carbonate, dehydrating beryllium hydroxide, or igniting metallic beryllium:

- BeCO3 → BeO + CO2

- Be(OH)2 → BeO + H2O

- 2 Be + O2 → 2 BeO

Igniting beryllium in air gives a mixture of BeO and the nitride Be3N2.[4] Unlike the oxides formed by the other group 2 elements (alkaline earth metals), beryllium oxide is amphoteric rather than basic.

Beryllium oxide formed at high temperatures (>800 °C) is inert, but dissolves easily in hot aqueous ammonium bifluoride (NH4HF2) or a solution of hot concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4).

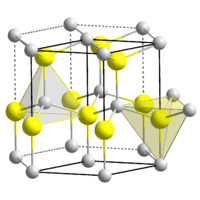

Structure

BeO crystallizes in the hexagonal wurtzite structure, featuring tetrahedral Be2+ and O2− centres, like lonsdaleite and w-BN (both of which it is isoelectronic with). In contrast, the oxides of the larger group 2 metals, i.e., MgO, CaO, SrO, BaO, crystallize in the cubic rock salt motif with octahedral geometry about the dications and dianions.[4] At high temperature the structure transforms to a tetragonal form.[6]

In the vapour phase, beryllium oxide is present as discrete diatomic molecules. In the language of valence bond theory, these molecules can be described as adopting sp orbital hybridisation, featuring two sigma and two pi bonds. The corresponding ground state is .. (2sσ)2(2sσ*)2(2pπ)4, where both degenerate π orbitals can be considered as dative bonds from oxygen towards beryllium.[7]

Applications

High-quality crystals may be grown hydrothermally, or otherwise by the Verneuil method. For the most part, beryllium oxide is produced as a white amorphous powder, sintered into larger shapes. Impurities, like carbon, can give a variety of colours to the otherwise colourless host crystals.

Sintered beryllium oxide is a very stable ceramic.[8] Beryllium oxide is used in rocket engines.

Beryllium oxide is used in many high-performance semiconductor parts for applications such as radio equipment because it has good thermal conductivity while also being a good electrical insulator. It is used as a filler in some thermal interface materials such as thermal grease.[9] Some power semiconductor devices have used beryllium oxide ceramic between the silicon chip and the metal mounting base of the package in order to achieve a lower value of thermal resistance than for a similar construction made with aluminium oxide. It is also used as a structural ceramic for high-performance microwave devices, vacuum tubes, magnetrons, and gas lasers. BeO has also been put forward as a moderator for proposed naval marine high-temperature gas-cooled reactors (MGCR).

Safety

BeO is carcinogenic and may cause chronic beryllium disease. Once fired into solid form, it is safe to handle as long as it is not subjected to any machining that generates dust.[10] Beryllium oxide ceramic is not a hazardous waste under federal law in the USA.

References

- ↑ "beryllium oxide – Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 27 March 2005. Identification and Related records. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ↑ Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-94690-X.

- 1 2 3 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0054". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 3 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ Raymond Aurelius Higgins (2006). Materials for Engineers and Technicians. Newnes. p. 301. ISBN 0-7506-6850-4.

- ↑ A.F. Wells (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry (5 ed.). Oxford Science Publications. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

- ↑ Fundamentals of Spectroscopy. Allied Publishers. pp. 234–. ISBN 978-81-7023-911-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ↑ Günter Petzow, Fritz Aldinger, Sigurd Jönsson, Peter Welge, Vera van Kampen, Thomas Mensing, Thomas Brüning"Beryllium and Beryllium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_011.pub2

- ↑ Greg Becker; Chris Lee & Zuchen Lin (2005). "Thermal conductivity in advanced chips — Emerging generation of thermal greases offers advantages". Advanced Packaging: 2–4. Archived from the original on June 21, 2000. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ Beryllium Oxide Safety

External links

- Beryllium Oxide MSDS from American Beryllia

- Beryllium Oxide Properties (solid form)

- IARC Monograph "Beryllium and Beryllium Compounds"

- International Chemical Safety Card 1325

- National Pollutant Inventory – Beryllium and compounds

- NIOSH Pocket guide to Chemical Hazards