Gowanus Canal

| Gowanus Canal | |

|---|---|

| Superfund site | |

|

An aerial view of the canal and its crossings. | |

| Geography | |

| City | Brooklyn, New York City |

| County | Kings County |

| State | New York |

| Coordinates | 40°40′23″N 73°59′49″W / 40.673°N 73.997°W |

Gowanus Canal | |

| Information | |

| CERCLIS ID | NYN000206222 |

| Contaminants | PAHs, VOCs, PCBs, pesticides, metals |

| Progress | |

| Proposed | 04/09/2009 |

| Listed | 03/04/2010 |

| List of Superfund sites | |

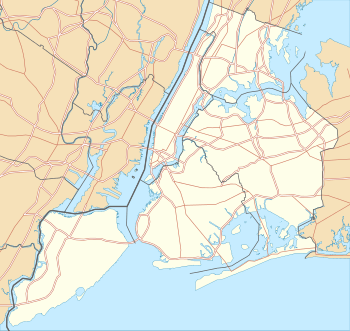

The Gowanus Canal is a canal in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, on the westernmost portion of Long Island. Connected to Gowanus Bay in Upper New York Bay, the canal borders the neighborhoods of Red Hook, Carroll Gardens, and Gowanus, all within South Brooklyn, to the west; Park Slope to the east; Boerum Hill and Cobble Hill to the north; and Sunset Park to the south. It is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) long.[1] There are seven bridges over the canal, carrying Union Street, Carroll Street (a landmark), Third Street, Ninth Street, Hamilton Avenue, the Gowanus Expressway, and the IND Culver Line of the New York City Subway.

Once a busy cargo transportation hub, the canal is now recognized as one of the most polluted bodies of water in the United States, and is a Superfund site.[2] The canal's history has paralleled the decline of domestic shipping via water. The canal is still used for waterborne transportation of goods, notably fuel oil, scrap metal and aggregates. Tugs and barges still navigate the canal daily. A legacy of serious environmental problems has beset the area from the time the canal arose from the local tidal wetlands and fresh water streams. In recent years, there has been a call once again for environmental cleanup. In addition, development pressures have brought speculation that the wetlands of the Gowanus should serve waterfront economic development needs which may not be compatible with environmental restoration.

Historical use

Mill creek

The Gowanus neighborhood originally surrounded Gowanus Creek, which consisted of a tidal inlet of navigable creeks in original saltwater marshland and meadows teeming with fish and other wildlife. Henry Hudson and Giovanni da Verrazzano both navigated the inlet in their explorations of New York Harbor. The first land patents within Breukelen (Brooklyn), including the land of the Gowanus, were issued by the Dutch Government from 1630 to 1664. In 1639, the leaders of New Netherland made one of the earliest recorded real estate deals in New York City history with the purchase of the area around the Gowanus Bay for construction of a tobacco plantation. The early settlers of the area named the waterway "Gowanes Creek" after Gouwane, sachem of the local Lenape tribe called the Canarsee, who lived and farmed on the shorelines.[3]

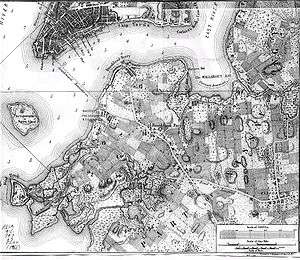

Adam Brouwer, who had been a soldier in the service of the Dutch West India Company, built and operated the first gristmill patented in New York at Gowanus (on land patented July 8, 1645, to Jan Evertse Bout). The tide-water gristmill on the Gowanus was the first in the town of Breukelen and was the first mill ever operated in New Netherland (located north of Union Street, west of Nevins Street, and next to Bond Street). A second mill (Denton's Mill, also called Yellow mill) was built on Denton's mill pond, after being granted permission to dredge from the creek to the mill pond once located between Fifth Ave and the present day canal at Carroll and Third Street. On May 26, 1664, several Breuckelen residents, headed by Brouwer, petitioned director general Peter Stuyvesant and his Council for permission to dredge a canal at their own expense through the land of Frederick Lubbertsen in order to supply water to run the mill. The petition was presented to the council on May 29, 1664, and the motion was granted. Another mill, Cole's Mill, was located just about at present day 9th Street, between Smith Street and the Canal. Cole's Mill Pond, located north of 9th street, occupied the present location of Public Place.[4]

In 1700, a settler, Nicholas Vechte, built a farmhouse of brick and stone now known as the Old Stone House, which later played a critical role in the 1776 Battle of Long Island, when American troops fought off the Redcoats long enough to allow George Washington to retreat.[5] This house sat at the south eastern edge of the Denton's Mill pond. Brower's Mill (also known as Freeks Mill, located at the present day intersection of Union and Nevins streets) can be seen in drawings depicting the "Battle of Brooklyn".

Throughout this period, a few Dutch farmers settled along the marshland and engaged in clamming of large oysters that became a notable first export to Europe. The six-foot (2 m) tides of the bay forced salt water up into the creek's meandering course, creating a brackish mix of water that was ideal for the bivalves, which often grew much larger than today but gradually shrank through a form of negative artificial selection. By the middle of the 19th century, the City of Brooklyn was the third most populous, and fastest growing, city in America and had incorporated the creek and farmland into a greater urban fabric with linear villages flourishing along the shore.[3]

Economic hub

The mills on the Gowanus were also home to public landing sites, connecting the water route to the old Gowanus road. As the local population grew and 19th-century industrial revolution reached Brooklyn, the need for larger navigational and docking facilities grew. Colonel Daniel Richards, a successful local merchant, advocated the building of a canal to benefit existing inland industries and drain the surrounding marshes for land reclamation that would raise property values.[6] In 1849, the New York Legislature authorized the construction of the Gowanus Canal by deepening Gowanus Creek, to transform it into a mile-and-a-half-long commercial waterway connected to Upper New York Bay. The full dredging of Gowanus Creek could not begin until a further act of the legislature in 1867. After exploring numerous alternative (and some more environmentally sound) designs, the final was chosen for its low price tag. United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Major David Bates Douglass was hired to design the canal, which was essentially complete by 1869. The cost of the construction came from assessments on the local residents of Brooklyn and State money.[7]

Despite its relatively short length, the Gowanus Canal was a hub for Brooklyn's maritime and commercial shipping activity. Factories, warehouses, tanneries, coal stores, and manufactured gas refineries sprang up as a result of its construction. Much of the brownstone quarried in New Jersey and the upper Hudson was placed on barges with lumber and brick and shipped through the canal to build the neighborhoods of Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, and Park Slope. In addition, the industrial sector around the canal grew substantially over time to include: stone and coal yards; flour mills; cement works, and manufactured gas plants; tanneries, factories for paint, ink, and soap; machine shops; chemical plants; and sulfur producers, all of which emitted substantial water and airborne pollutants. The canal was the first site where chemical fertilizers were manufactured.[8]

With as many as 700 new buildings a year constructed, the South Brooklyn region grew at a remarkable rate. Thriving industry brought many new people to the area but important questions about wastewater sanitation had not been properly addressed to handle such growth. All the sewage from the new buildings drained downhill, into the Gowanus. The building of new sewer connections only compounded the problem by discharging raw sewage from neighborhoods even farther away into the Canal. By the turn of the century, the combination of industrial pollutants and runoff from storm water, fortified with the products of the new sewage system, rendered the waterway a repository of rank odors, euphemistically called by wise-cracking locals "Lavender Lake". After World War I, with six million annual tons of cargo produced and trafficked though the waterway, the Gowanus Canal became the nation's busiest commercial canal, and arguably the most polluted. The heavy sewage flow into the canal required regular dredging to keep the waters navigable.

With much fanfare, the US Army Corps of Engineers completed its last dredging of the canal in 1955 and soon afterward abandoned its regular dredging schedule, deeming it to be no longer cost-effective. Brooklyn's fuel trade was already converting from coal and artificial gas to petroleum, which was served by the wider and deeper Newtown Creek, and natural gas, which arrived by pipeline. With the early 1960s growth of containerization, New York's loss of industrial waterfront jobs during this period was evident on the canal and, with the failure of the city sewage and pump station infrastructure along the canal, Gowanus was used as a derelict dumping place. Remaining barge traffic mostly carries fuel oil, sand, gravel and scrap metal is exported; the canal still serves as a port moving goods in and out of Brooklyn. At this point, the issue of revitalizing of the Gowanus area was raised. In 1975 the City of New York established a Gowanus Industrial Renewal Plan for the area, which remained in effect until the year 2011. Since 1975, the surrounding community has been calling for the city, state, and federal governments to bring the full power of the Clean Water Act to bear on the environmental conditions left behind in this once thriving urban/industrial waterway.

Degeneration

At the time the canal was built, several designs were proposed for it, some with lock systems that would have allowed daily flushing of the whole waterway. But these designs were considered too expensive, and as a result the Gowanus Canal was constructed with significant design flaws, but within budget. There was no through-flow of water and the canal was open at only one end, in the hope that the tides would be enough to flush the waterway. But with the canal's wooden and concrete embankments, the strong tides of fresh diurnal doses of oxygenated water from New York Harbor were barred from flowing into the 1.8 mile (3 km) channel. Water quality studies have found the concentration of oxygen in the canal to be just 1.5 parts per million, well below the minimum 4 parts per million needed to sustain life.[9] With the high level of development in the Gowanus watershed area, excessive nitrates and pathogens are constantly flowing into the canal, further depleting the oxygen and creating breeding grounds for the pathogens responsible for the canal's odor.

The opaqueness of the Gowanus water obstructs sunlight to one third of the 6 feet (1.8 m) needed for aquatic plant growth. Rising gas bubbles betray the decomposition of sewage sludge that on a warm, sultry day produces the canal's notable ripe stench. The murky depths of the canal conceal the remnants of its industrial past: cement, oil, mercury, lead,[10] multiple volatile organic compounds,[10] PCBs, coal tar, and other contaminants. A 2007 Science Line report found gonorrhea[10][11] and unidentified organisms in the canal. In 1951, with the opening of the elevated Gowanus Expressway over the waterway, easy access for trucks and cars catalyzed industry slightly, but with 150,000 vehicles passing overhead each day, the expressway also deposits tons of toxic emissions into the air and water beneath.[9]

There is an urban legend that the canal served as a dumping ground for the Mafia.[12] In Jonathan Lethem's Motherless Brooklyn, a character refers to it as "the only body of water in the world that is 90 percent guns." In Lavender Lake, a 1998 documentary film about the Gowanus Canal by Alison Prete, two cops discuss the recent discovery by fishermen of a suitcase full of human body parts that was taken from the waterway.[13] In Joseph O'Neill's novel Netherland, the remains of one of the protagonists are found in the Gowanus Canal.[14]

Flushing the canal

The first step to ameliorate pollution in the canal was the construction in the 1890s of the Bond Street sewer pipeline that carried sewage out into the harbor, but this proved inadequate. In the first attempt to improve flow at the northern, closed end of the canal, the "Big Sewer" was constructed from Marcy Avenue in Prospect Heights, down Green Ave to 4th Avenue and into the canal at Butler Street. This sewer design was featured in Scientific American for its innovative construction method and size. The area this sewer ran through was known as "The Flooded District," and it was believed that this new sewer would serve two purposes: to drain the flooded district, and to use the flow of that excessive water to move the water of the upper Gowanus Canal. Headlines in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper declared it an engineering blunder shortly after its construction. The Big Sewer still exists under the streets of Brooklyn today.

By 1910, complaints were being made about the water of canal being almost solid waste,[15] which provoked the installation of the Flushing Tunnel on June 21, 1911, which for a time supplied clean water to the upper reaches of the canal through the brick-lined 1.2 miles (1.9 km) tunnel via Butler Street to Buttermilk Channel between Brooklyn and Governors Island. Unfortunately, this too failed. Aside from numerous operational glitches, a long series of problems and mistakes occurred throughout the 1960s, culminating when a city worker dropped a manhole cover that severely damaged a pump system[15] already suffering from the effect of the corrosive salt water. The Clean Water Act had not yet been passed, and the city, stretched for funds at the time, did nothing to address the issue. As a result of the unrepaired damage to the Flushing Tunnel, and the long stretch of economic recession, the waters of the canal lay stagnant and under-used for years.

According to the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), plans to reactivate the Flushing Tunnel pump were proposed in 1982. But, due to bureaucratic delays, the DEP did not take up the project until 1994. The tunnel was finally reactivated in 1999. The new design employed a 600 horsepower (450 kW) motor, that pumped an average rate of 200,000,000 US gallons (760,000,000 l; 170,000,000 imp gal) a day of aerated water from Buttermilk Channel of the East River into the head end of the canal. Although water was circulating through the tunnel, it can only be pumped 11 hours a day, due to tidal forces. Water quality has now improved, or at least the quality of water samples taken while the Flushing Pump is operating.[16] Another attempt to control pollution, the construction of the $230 million Red Hook Water Pollution Control Plant in 1987, had similar unsatisfactory results. The Red Hook Treatment plant collected waste from the existing Bond Street sewer that had been dumping into the harbor, but did not take up any additional waste that still spills into the canal from the sewer system's 14 combined sewer overflow (CSO) points. The city has yet to modify the sewer system to reduce sewage overflows into the Gowanus.

Environmental cleanup and redevelopment

Redevelopment plans

In 1999, Assemblywoman Joan Millman allocated $100,000 to the Gowanus Canal Community Development Corporation (GCCDC) to produce and distribute a bulkhead study and public access document. The following year, GCCDC received $270,000 from the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation to construct three street-end public open spaces along the Gowanus Canal through the city's Green Street program. An additional $270,000 was funded by Governor George E. Pataki to create a revitalization plan in 2001 and then allocated $100,000 in capital funds in 2002 to implement a pilot project on the shoreline. In 2003, Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez allocated an additional $225,000 to create a comprehensive community development plan. Today this organization relies on community volunteers to maintain and clean these Green Street Projects. The community lacks a community centered redevelopment plan.[3]

In 2002, the United States Army Corps of Engineers entered into a cost-sharing agreement with the DEP to collaborate on a $5 million Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study of the Gowanus Canal area to be completed in 2005, studying possible alternatives for ecosystem restoration such as dredging, and wetland and habitat restoration. Discussions turned to breaking down the hard edges of the canal in order to restore some of the natural processes to improve the overall environment of the Gowanus wetlands area. The DEP also initiated the Gowanus Canal Use and Standards Attainment project, to meet the City's obligations under the Clean Water Act. As of the summer 2009, the joint NYC/Army Corps Feasibility study has not been completed.[3]

In early 2006, the problem of wastewater management arose during a controversy over a planned Brooklyn Nets Arena in nearby central Brooklyn. The project at that point, now called Pacific Park, was to include a basketball arena and 17 skyscrapers, with the resulting sewage would flow into antiquated combined sewers that can overflow when it rains.[17][18] The Gowanus Canal has 14 combined sewer overflow points, so the fear is that the additional wastewater from the arena would lead to more frequent overflows in the canal.

As the industrial Brooklyn cityscape evolves, new development plans have been debated for the Gowanus Canal and the land abutting it. The adjacent neighborhood to the east (4th Avenue) was rezoned for high density residential use with a strong commercial component. With brownfield redevelopment incentives offered by the State of New York, developers look to this land as another place to build, with substantial help of public money.

In February 2009, the city of New York granted a zoning change to the developer, Toll Brothers Inc., allowing for a 480-unit, twelve-story, super-block residential project, the first permitted along the waterway. Toll Brothers abandoned this project in 2010 when the Gowanus Canal was declared a Superfund cleanup site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,[19] despite the city's claim that it could fix the problem more quickly.[15]

Usage

Paving the way for recreational use of the canal has been the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club (founded in 1999), and The Urban Divers Estuary Conservancy (founded in 1998), two organizations that are dedicated to providing waterfront access and education related to the estuary and bordering shoreline of the canal. During the 2003 season, over 1,000 individuals, including more than 200 youths, participated in Dredger Canoe Club programs, logging over 2,000 trips on the Gowanus Canal. The NY Harbor report for that same year showed the Gowanus to have the highest level of pathogens in the entire harbor.

A 9.4 acres (4 ha) U.S. Postal Service site on the east side of the Ninth Street canal crossing became available for commercial development. Development groups have not taken their eye off a whole range of possible projects for the site. It has been proposed as the Brooklyn Commons, an entertainment and retail complex featuring a multiplex cinema, a bowling alley, shops and restaurants. After controversy, a lawsuit, and a rival proposal for an IKEA store, a large Lowe's store was built and opened on April 30, 2004, with an adjacent public promenade overlooking the canal. The IKEA company, previously rejected from the Ninth Street location for traffic congestion, opened on the south end of Red Hook on the harbor waterway. That project was objected to by community organizations in the Red Hook and Gowanus neighborhoods.

Another site at Smith and 4th street was taken by the city in 1975 and designated a Public Place, for use as "public recreation space". Despite this legal standing of the Public Place, developers have continually proposed using this site for other possibilities. National Grid is accountable for a cleanup of the pollution left behind on the site after years of coal gas manufacture. Upon completion of this cleanup, the site was to be turned over to the parks department.[20]

Activism

In November 2006, HABITATS, a festival dedicated to "local action as global wisdom", celebrated the Gowanus Canal through environmental conferences, collaborative art, educational programs and interactive walks around the area.[21] The canal has been the home to various arts organizations. Issue Project Room once organized art events, and the Yard, an outdoor concert space, opened in the summer of 2007 near the Carroll Street bridge.

Cleanup efforts

In April 2009, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed that the canal be listed as a Superfund cleanup site.[22] This action was supported by the state Department of Environmental Conservation, which had requested help from the EPA to address the canal's environmental problems. In May 2009, the city stepped forward to oppose the Superfund listing and offered, for the first time, to produce a Gowanus cleanup plan that would match the work of a Superfund cleanup, but with a promise to accomplish it faster. The city stated that it could now achieve a faster cleanup than EPA because the city would fund the cleanup through taxpayer dollars from the state and city levels, while the EPA would seek its funding from the polluters.[23] In 2009, the nonprofit Gowanus Canal Conservancy was founded, which partners with the EPA, the city Department of Environmental Protection (NYCDEP), groups like Riverkeeper and universities such as Cornell and Rutgers.[24] Among other things, it hosts monthly composting events. On March 4, 2010, the EPA announced that it had placed the Gowanus Canal on its Superfund National Priorities List.[25][26]

By 2013, the NYCDEP was planning to reduce the sewage content of the canal by repairing a tunnel that flushes fresh water into the Gowanus. The repair will not completely eliminate the sewage problem.[27] The EPA has suggested seven plans for the clean up.[28] The Village Voice reported two scenarios as most viable, estimated at taking ten years to complete and costing around $350–$450 million. The first step in the plans is dredging, scheduled to begin 2016. The second is to lay down one of two different proposed "caps". One cap over the still-polluted canal bed would be made of concrete. The second would have first a layer of clay to absorb pollutants, a layer of sand to act as a buffer, and then a layer of rocks to anchor that floor.[29] Some express concern that the clean-up poses a health risk.[30]

On September 27, 2013, the EPA approved a clean-up plan for the Gowanus Canal. The plan is to cost $506 million and should be completed by 2022. The plan divides the canal into three segments: The upper segment runs from the top of the canal to 3rd Street, the middle segment runs from 3rd Street to just south of the Hamilton Avenue Bridge and the lower segment runs from the Hamilton Avenue Bridge to the mouth of the canal. The plan entails removing contaminated sediment from the bottom of canal by dredging, capping the dredged areas and implementing controls on combined sewer overflows to prevent future contamination. It also involves excavating and restoring approximately 475 feet (145 m) of the former 1st Street Basin and 25 feet (7.6 m) of the former 5th Street Basin.[31]

The layer of toxic sediment in the canal averages 10 feet (3.0 m) thick, and at some spots reaches 20 feet (6.1 m).[32] EPA will remove approximately 307,000 cubic yards of highly contaminated sediment from the upper and middle segments and 281,000 cubic yards of contaminated sediment from the lower segment. The dredged sediment will be treated at an off-site facility.[31]

Following dredging, in areas of the canal where contamination has permeated the underlying sediment, EPA will cap with multiple layers of clean material. The multi-layer cap consists of an “active” layer made of a specific type of clay that will remove contamination that could well up from below, an “isolation” layer of sand and gravel that will ensure that the contaminants are not exposed, and an “armor” layer of heavier gravel and stone to prevent erosion of the underlying layers from boat traffic and canal currents. Finally, sufficient clean sand will be placed on top of the “armor” layer to fill in the voids between the stones and to establish sufficient depth in order to restore the canal bottom as a habitat. In the middle and upper segment of the canal where the native sediment is contaminated with liquid coal tar, the EPA will stabilize that sediment by mixing it with concrete or similar materials. The stabilized areas will then be covered with the multiple layer cap as described above.[31]

As the Superfund model requires the EPA to seek restitution from the Potentially Responsible Parties (PRPs), the estimated cost of the cleanup plan is to be spread among more than three dozen entities, mostly companies and a few government entities like the City of New York and the United States Navy, for ship work that polluted the canal. Many of the original businesses that once operated alongside the canal have since merged, changed names or moved away, including Brooklyn Union Gas, which eventually became a part of National Grid, Continental Oil and Standard Oil. When companies have been sold or merged, the successor company as well as the current property owner assume the liability. Companies that produced or transported the hazardous substances are also considered responsible.[33] The EPA Superfund Gowanus report has identified the major PRPs as National Grid and New York City.[31]

Wildlife

By 2014, it has been reported that oysters, white perch, herring, striped bass, anchovies, jellyfish, crabs, herons, egrets, bats and Canada geese, have started to live in and around the waterway.[34][15] Even so, the water continues to be contaminated by E. coli and gonorrhea, among other pathogens, and nothing caught in the canal is safe to eat.[15]

On January 26, 2013, a minke whale entered the canal at low tide, was unable to get out, and died.[35][15] The necropsy on showed it was middle-aged and sickly before becoming trapped. It had kidney stones, gastric ulcers and parasites.[36]

There has also been discovered on the bottom of the canal a new form of life colloquially called "white stuff", which is a co-operative mix of bacteria, protozoa, chemicals and other substances. The white stuff appears to act together to find food, and the biologogical components exchange genes and excrete material that acts as an antibiotic to protect it from toxins in the water. There is hope that thesee excretions may lead to new antibiotic drugs.[37]

In popular culture

In 2014, So What? Press published an issue of its comic series Tales of the Night Watchman, entitled "It Came from the Gowanus Canal", about a toxic sludge monster who lives in the canal and takes revenge on a gangster who once dumped bodies there. It was written by Dave Kelly and illustrated by Molly Ostertag.[38] The publisher also produced a fake movie poster in conjunction with the Gowanus Souvenir Shop based on the issue in 2015.[39]

In the TV series "Blue Bloods" season 5 episode 14, "The Poor Door" (2015), Jamie's partner Edit asks him to choose between licking the tile on the Lincoln tunnel or skinny dipping in Gowanus canal.

See also

- List of Superfund sites in New York

- History of New York City transportation

- The Gowanus Memorial Artyard

- Geography of New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary

- Newtown Creek

- Arthur Kill

References

- ↑ Berger, Joseph (May 6, 2013) "E.P.A. Plan to Clean Up Gowanus Canal Meets Local Resistance" The New York Times

- ↑ Buiso, Gary (November 8, 2010). "Feds: We know where Gowanus Canal filth is". The Brooklyn Paper. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 The Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club, "Gowanus Canal History", accessed May 12, 2004, revised April 2, 2004

- ↑ Stiles, Henry R., History of the City of Brooklyn: Including the old town and village of Brooklyn, the town of Bushwick, and the village and city of Williamsburgh". Brooklyn, N.Y.: Pub. by subscription, 1867-1870. July 5, 2005

- ↑ "Permanent Revolution". New York. September 10, 2012.

- ↑ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, Carroll Gardens Historic District, 1973

- ↑ Wheelwright, Peter., Project III Program Statement: Gowanus Canal, River Projects Exhibition - Van Alen Institute for Public Architecture, 1998

- ↑ Terry, Virginia (April 16, 2003). "Imaging the City: Gowanus Canal". Metropolital Waterfront Alliance.

- 1 2 Held, James E., "Currents of Change: Can Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal Be Cleaned Up?", E – The Environmental Magazine, 10.3, 1999

- 1 2 3 Phillips, Kristin Elise (September 26, 2007). "Tainted Lavender". Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ↑ "Gowanus: The Whole Foods Lot".

- ↑ Freudenheim, Ellen (January 1, 2010). "Gowanus Canal—Truth or Fiction that "Bodies Were Dumped Here?"". About.com Travel. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ http://vimeo.com/20937049

- ↑ Joseph O'Neill (2009). Netherland. Harper Perennial. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-00-727570-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Eldredge, Niles & Horenstein, Sidney (2014), Concrete Jungle: New York City and Our Last Best Hope for a Sustainable Future, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-27015-2

- ↑ New York City Department of Environmental Protection, City Activates Gowanus Canal Flushing Tunnel, Publication 99-28, New York: April 30, 1999

- ↑ Cohen, Ariella (March 4, 2006). "Study: Yards feces to canal; Buddy: Developers' poop stinks" (PDF). The Brooklyn Paper. p. 3. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ↑ The Great Stink: When England was disgusting (and why America’s rivers still are)

- ↑ Buiso, Gary (July 9, 2010). "Toll Brothers is officially stigmatized by the Superfund". The Brooklyn Paper. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Cleanup of the Gowanus Canal", Gowanus Superfund website. Accessed: November 14, 2014

- ↑ Habitats, Celebrating the revitalization of the Historic Gowanus Canal, accessed November 7, 2006.

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. New York, NY. "Gowanus Canal Superfund Site." Updated February 4, 2010.

- ↑ Navarro, Mireya (July 2, 2009). "City Proposes New Plan for Gowanus Canal Cleanup". The New York Times. p. A19.

- ↑ "About: Partners". Gowanus Canal Conservancy website.

- ↑ Navarro, Mireya (March 2, 2010). "Gowanus Canal Gets Superfund Status". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Gowanus Canal site description" (PDF). EPA. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ Moskowitz, Peter (June 14, 2013). "For Local Residents, a Mission to Clean Up the Gowanus Canal". The New York Times. Gowanus Canal (NYC). Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ "EPA Gives Seven Options For Gowanus Canal Cleanup | New York League of Conservation Voters". Nylcv.org. January 5, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ Bekiempis, Victoria (January 30, 2012). "Gross Gowanus Canal: Cleanup Conversations Continue". Village Voice. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ Durkin,, Eric (January 21, 2012). "Gowanus Canal cleanup by National Grid is blasted by Gowanus Canal Community Development Corp. as a possible health risk". New York Daily News. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Region 2 Superfund: Gowanus Canal". EPA Superfund. U.S.Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ↑ Record of Decision: Gowanus Canal Superfund Site Brooklyn, Kings County, New York (PDF). September 27, 2013. p. 15. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Gregory, Kia (September 26, 2013). "Industry Still Churns, Even as Cleanup Plan Proceeds for a Canal". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Nuwer, Rachel, "On the Waterfront: Superfund Makeover," Edible Brooklyn, No. 33, Spring 2014.

- ↑ Long, Colleen (January 26, 2013). "Dolphin Dies Amid NY Canal's Industrial Pollution". ABC News. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Necropsy Reveals Dolphin That Died In Gowanus Canal Had String Of Health Problems". CBS News New York. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ↑ Eldredge, Niles & Horenstein, Sidney (2014), Concrete Jungle: New York City and Our Last Best Hope for a Sustainable Future, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, p. 202, ISBN 978-0-520-27015-2

- ↑ Dillon, Bryant (August 7, 2014). "'Tales of The Night Watchman Presents: It Came from the Gowanus Canal' - Comic Book Review (Revenge Is a Dish Best Served Slimy)". Fanbase Press. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Davis, Nicole (December 9, 2015). "Your Ideal Week: Dec. 10 – Dec. 16". Brooklyn Based. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

External links

- Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club

- The Gowanus Canal at southbrooklyn.net

- The Urban Divers Estuary Conservancy

- Gowanus Canal Conservancy

- Gowanus Institute

- Cleaning up a local superfund site: Natalie Loney at TEDxGowanus on YouTube (March 25, 2014)