Graphical user interface

In computer science, a graphical user interface (GUI /ɡuːiː/), is a type of user interface that allows users to interact with electronic devices through graphical icons and visual indicators such as secondary notation, instead of text-based user interfaces, typed command labels or text navigation. GUIs were introduced in reaction to the perceived steep learning curve of command-line interfaces (CLIs),[1][2][3] which require commands to be typed on a computer keyboard.

The actions in a GUI are usually performed through direct manipulation of the graphical elements.[4] Beyond computers, GUIs are used in many handheld mobile devices such as MP3 players, portable media players, gaming devices, smartphones and smaller household, office and industrial controls. The term GUI tends not to be applied to other lower-display resolution types of interfaces, such as video games (where head-up display (HUD)[5] is preferred), or not restricted to flat screens, like volumetric displays[6] because the term is restricted to the scope of two-dimensional display screens able to describe generic information, in the tradition of the computer science research at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC).

User interface and interaction design

Designing the visual composition and temporal behavior of a GUI is an important part of software application programming in the area of human–computer interaction. Its goal is to enhance the efficiency and ease of use for the underlying logical design of a stored program, a design discipline named usability. Methods of user-centered design are used to ensure that the visual language introduced in the design is well-tailored to the tasks.

The visible graphical interface features of an application are sometimes referred to as chrome or GUI (pronounced gooey).[7][8] Typically, users interact with information by manipulating visual widgets that allow for interactions appropriate to the kind of data they hold. The widgets of a well-designed interface are selected to support the actions necessary to achieve the goals of users. A model–view–controller allows a flexible structure in which the interface is independent from and indirectly linked to application functions, so the GUI can be customized easily. This allows users to select or design a different skin at will, and eases the designer's work to change the interface as user needs evolve. Good user interface design relates to users more, and to system architecture less.

Large widgets, such as windows, usually provide a frame or container for the main presentation content such as a web page, email message or drawing. Smaller ones usually act as a user-input tool.

A GUI may be designed for the requirements of a vertical market as application-specific graphical user interfaces. Examples include automated teller machines (ATM), point of sale (POS) touchscreens at restaurants,[9] self-service checkouts used in a retail store, airline self-ticketing and check-in, information kiosks in a public space, like a train station or a museum, and monitors or control screens in an embedded industrial application which employ a real-time operating system (RTOS).

By the 1990s, cell phones and handheld game systems also employed application specific touchscreen GUIs. Newer automobiles use GUIs in their navigation systems and multimedia centers, and/or navigation multimedia center combinations.

Examples

- Sample graphical desktop environments

-

_in_GNOME_3.8.png)

GNOME Shell (Gnome‑3)

-

KDE Plasma (KDE 4)

-

A twm X Window System environment

-

Windows on a Wayland compositor

Components

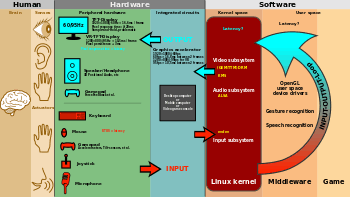

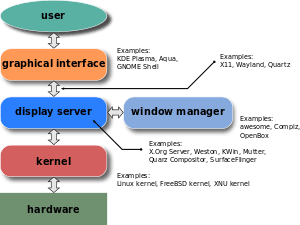

A GUI uses a combination of technologies and devices to provide a platform that users can interact with, for the tasks of gathering and producing information.

A series of elements conforming a visual language have evolved to represent information stored in computers. This makes it easier for people with few computer skills to work with and use computer software. The most common combination of such elements in GUIs is the windows, icons, menus, pointer (WIMP) paradigm, especially in personal computers.

The WIMP style of interaction uses a virtual input device to control the position of a pointing device, most often a mouse, and presents information organized in windows and represented with icons. Available commands are compiled together in menus, and actions are performed making gestures with the pointing device. A window manager facilitates the interactions between windows, applications, and the windowing system. The windowing system handles hardware devices such as pointing devices, graphics hardware, and positioning of the pointer.

In personal computers, all these elements are modeled through a desktop metaphor to produce a simulation called a desktop environment in which the display represents a desktop, on which documents and folders of documents can be placed. Window managers and other software combine to simulate the desktop environment with varying degrees of realism.

Post-WIMP interfaces

Smaller mobile devices such as personal digital assistants (PDAs) and smartphones typically use the WIMP elements with different unifying metaphors, due to constraints in space and available input devices. Applications for which WIMP is not well suited may use newer interaction techniques, collectively termed post-WIMP user interfaces.[10]

As of 2011, some touchscreen-based operating systems such as Apple's iOS (iPhone) and Android use the class of GUIs named post-WIMP. These support styles of interaction using more than one finger in contact with a display, which allows actions such as pinching and rotating, which are unsupported by one pointer and mouse.[11]

Interaction

Human interface devices, for the efficient interaction with a GUI include a computer keyboard, especially used together with keyboard shortcuts, pointing devices for the cursor (or rather pointer) control: mouse, pointing stick, touchpad, trackball, joystick, virtual keyboards, and head-up displays (translucent information devices at the eye level).

There are also actions performed by programs that affect the GUI. For example, there are components like inotify or D-Bus to facilitate communication between computer programs.

History

Precursors

A precursor to GUIs was invented by researchers at the Stanford Research Institute, led by Douglas Engelbart. They developed the use of text-based hyperlinks manipulated with a mouse for the On-Line System (NLS). The concept of hyperlinks was further refined and extended to graphics by researchers at Xerox PARC and specifically Alan Kay, who went beyond text-based hyperlinks and used a GUI as the main interface for the Xerox Alto computer, released in 1973. Most modern general-purpose GUIs are derived from this system.

Ivan Sutherland developed a pointer-based system called the Sketchpad in 1963. It used a light pen to guide creating and manipulating objects in engineering drawings.

PARC user interface

The PARC user interface consisted of graphical elements such as windows, menus, radio buttons, and check boxes. The concept of icons was later introduced by David Canfield Smith, who had written a thesis on the subject under the guidance of Kay.[12][13][14] The PARC user interface employs a pointing device along with a keyboard. These aspects can be emphasized by using the alternative term and acronym for windows, icons, menus, pointing device (WIMP).

Evolution

Following PARC the first GUI-centric computer operating model was the Xerox 8010 Information System (Xerox Star) in 1981,[15][16] followed by the Apple Lisa (which presented the concept of menu bar and window controls) in 1983, the Apple Macintosh 128K in 1984, and the Atari ST with Digital Research's GEM, and Commodore Amiga in 1985.

Visi On was released in 1983 for the IBM PC compatible computers, but was never popular due to its high hardware demands.[17] Nevertheless, it was a crucial influence on the contemporary development of Microsoft Windows.[18]

Apple, Digital Research, IBM and Microsoft used many of Xerox's ideas to develop products, and IBM's Common User Access specifications formed the basis of the user interfaces used in Microsoft Windows, IBM OS/2 Presentation Manager, and the Unix Motif toolkit and window manager. These ideas evolved to create the interface found in current versions of Microsoft Windows, and in various desktop environments for Unix-like operating systems, such as macOS and Linux. Thus most current GUIs have largely common idioms.

Popularization

GUIs were a hot topic in the early 1980s. The Apple Lisa was released in 1983, and various windowing systems existed for DOS operating systems (including PC GEM and PC/GEOS). Individual applications for many platforms presented their own GUI variants.[19] Despite the GUIs advantages, many reviewers questioned the value of the entire concept,[20] citing hardware limits, and problems in finding compatible software.

In 1984, Apple released a television commercial which introduced the Apple Macintosh during the telecast of Super Bowl XVIII by CBS,[21] with allusions to George Orwell's noted novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four. The goal of the commercial was to make people think about computers, identifying the user-friendly interface as a personal computer which departed from prior business-oriented systems,[22] and becoming a signature representation of Apple products.[23]

Accompanied by an extensive marketing campaign,[24] Windows 95 was a major success in the marketplace at launch and shortly became the most popular desktop operating system.

In 2007, with the iPhone[25] and later in 2010 with the introduction of the iPad,[26] Apple popularized the post-WIMP style of interaction for multi-touch screens, and those devices were considered to be milestones in the development of mobile devices.[27][28]

The GUIs familiar to most people as of the mid-2010s are Microsoft Windows, OS X, and the X Window System interfaces for desktop and laptop computers, and Android, Apple's iOS, Symbian, BlackBerry OS, Windows Phone, Palm OS-WebOS, and Firefox OS for handheld (smartphone) devices.

Comparison to other interfaces

Command-line interfaces

Since the commands available in command line interfaces can be many, complex operations can be performed using a short sequence of words and symbols. This allows greater efficiency and productivity once many commands are learned,[1][2][3] but reaching this level takes some time because the command words may not be easily discoverable or mnemonic. Also, using the command line can become slow and error-prone when users must enter long commands comprising many parameters and/or several different filenames at once. However, windows, icons, menus, pointer (WIMP) interfaces present users with many widgets that represent and can trigger some of the system's available commands.

GUIs can be made quite hard when dialogs are buried deep in a system, or moved about to different places during redesigns. Also, icons and dialog boxes are usually harder for users to script.

WIMPs extensively use modes, as the meaning of all keys and clicks on specific positions on the screen are redefined all the time. Command line interfaces use modes only in limited forms, such as for current directory and environment variables.

Most modern operating systems provide both a GUI and some level of a CLI, although the GUIs usually receive more attention. The GUI is usually WIMP-based, although occasionally other metaphors surface, such as those used in Microsoft Bob, 3dwm, or File System Visualizer (FSV).

GUI wrappers

Graphical user interface (GUI) wrappers circumvent the command-line interface versions (CLI) of (typically) Linux and Unix-like software applications and their text-based user interfaces or typed command labels. While command-line or text-based application allow users to run a program non-interactively, GUI wrappers atop them avoid the steep learning curve of the command-line,[1][2][3] which requires commands to be typed on the keyboard. By starting a GUI wrapper, users can intuitively interact with polipo, start, stop, and change its working parameters, through graphical icons and visual indicators of a desktop environment, for example. Applications may also provide both interfaces, and when they do the GUI is usually a WIMP wrapper around the command-line version. This is especially common with applications designed for Unix-like operating systems. The latter used to be implemented first because it allowed the developers to focus exclusively on their product's functionality without bothering about interface details such as designing icons and placing buttons. Designing programs this way also allows users to run the program in a shell script. An example of this basic design could be the specialized polipo command-line web proxy server, which has some connected GUI wrapper projects, e.g., for Windows OS (solipo[29]), OS X (dolipo[30]), and Android (polipoid[31]).

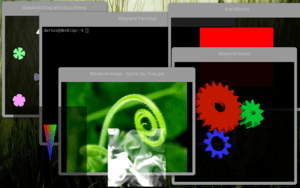

Three-dimensional user interfaces

For typical computer displays, three-dimensional is a misnomer—their displays are two-dimensional. Semantically, however, most graphical user interfaces use three dimensions. With height and width, they offer a third dimension of layering or stacking screen elements over one another. This may be represented visually on screen through an illusionary transparent effect, which offers the advantage that information in background windows may still be read, if not interacted with. Or the environment may simply hide the background information, possibly making the distinction apparent by drawing a drop shadow effect over it.

Some environments use the methods of 3D graphics to project virtual three dimensional user interface objects onto the screen. These are often shown in use in science fiction films (see below for examples). As the processing power of computer graphics hardware increases, this becomes less of an obstacle to a smooth user experience.

Three-dimensional graphics are currently mostly used in computer games, art, and computer-aided design (CAD). A three-dimensional computing environment can also be useful in other uses, like molecular graphics and aircraft design.

Several attempts have been made to create a multi-user three-dimensional environment, including the Croquet Project and Sun's Project Looking Glass.

Technologies

The use of three-dimensional graphics has become increasingly common in mainstream operating systems, from creating attractive interfaces, termed eye candy, to functional purposes only possible using three dimensions. For example, user switching is represented by rotating a cube which faces are each user's workspace, and window management is represented via a Rolodex-style flipping mechanism in Windows Vista (see Windows Flip 3D). In both cases, the operating system transforms windows on-the-fly while continuing to update the content of those windows.

Interfaces for the X Window System have also implemented advanced three-dimensional user interfaces through compositing window managers such as Beryl, Compiz and KWin using the AIGLX or XGL architectures, allowing use of OpenGL to animate user interactions with the desktop.

Another branch in the three-dimensional desktop environment is the three-dimensional GUIs that take the desktop metaphor a step further, like the BumpTop, where users can manipulate documents and windows as if they were physical documents, with realistic movement and physics.

The zooming user interface (ZUI) is a related technology that promises to deliver the representation benefits of 3D environments without their usability drawbacks of orientation problems and hidden objects. It is a logical advance on the GUI, blending some three-dimensional movement with two-dimensional or 2.5D vector objects. In 2006, Hillcrest Labs introduced the first zooming user interface for television.[32]

In science fiction

Three-dimensional GUIs appeared in science fiction literature and films before they were technically feasible or in common use. For example; the 1993 American film Jurassic Park features Silicon Graphics' three-dimensional file manager File System Navigator, a real-life file manager for Unix operating systems. The film Minority Report has scenes of police officers using specialized 3d data systems. In prose fiction, three-dimensional user interfaces have been portrayed as immersible environments like William Gibson's Cyberspace or Neal Stephenson's Metaverse. Many futuristic imaginings of user interfaces rely heavily on object-oriented user interface (OOUI) style and especially object-oriented graphical user interface (OOGUI) style.[33]

See also

- Apple Computer, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp.

- Console user interface

- Computer icon

- Distinguishable interfaces

- Ergonomics

- General Graphics Interface (software project)

- Look and feel

- Natural user interface

- Ncurses

- Object-oriented user interface

- Organic user interface

- Rich Internet application

- Skeuomorph

- Skin (computing)

- Theme (computing)

- Text entry interface

- User interface design

- Vector-based graphical user interface

References

- 1 2 3 Computerhope.com

- 1 2 3 Technet.com

- 1 2 3 Technet.com

- ↑ "window manager Definition". PC Magazine. Ziff Davis Publishing Holdings Inc. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ↑ Greg Wilson (2006). "Off with Their HUDs!: Rethinking the Heads-Up Display in Console Game Design". Gamasutra. Retrieved February 14, 2006.

- ↑ "GUI definition". Linux Information Project. October 1, 2004. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ↑ The Jargon Book, "Chrome"

- ↑ Jakob Nielsen. "Browser and GUI Chrome".

- ↑ The ViewTouch restaurant system by Giselle Bisson

- ↑ IEEE.org.

- ↑ Reality-Based Interaction: A Framework for Post-WIMP Interfaces

- ↑ Lieberman, Henry. "A Creative Programming Environment, Remixed", MIT Media Lab, Cambridge.

- ↑ Salha, Nader. "Aesthetics and Art in the Early Development of Human-Computer Interfaces", October 2012.

- ↑ Smith, David. "Pygmalion: A Creative Programming Environment", 1975.

- ↑ The first GUIs

- ↑ Xerox Star user interface demonstration, 1982

- ↑ "VisiCorp Visi On".

The Visi On product was apparently not intended for the home user. It was designed and priced for high end corporate workstations. The hardware it required was quite a bit for 1983. It required a minimum of 512k of ram and a hard drive (5 megs of space).

- ↑ A Windows Retrospective, PC Magazine Jan 2009.

- ↑ "Magic Desk I for Commodore 64".

- ↑ "Value of Windowing is Questioned".

- ↑ Friedman, Ted (October 1997). "Apple's 1984: The Introduction of the Macintosh in the Cultural History of Personal Computers". Archived from the original on October 5, 1999.

- ↑ Friedman, Ted (2005). "Chapter 5: 1984". Electric Dreams: Computers in American Culture. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-2740-9. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ↑ Grote, Patrick (October 29, 2006). "Review of Pirates of Silicon Valley Movie". DotJournal.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ↑ Washington Post (August 24, 1995). "With Windows 95's Debut, Microsoft Scales Heights of Hype". Washington Post. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ↑ Mather, John. iMania, Ryerson Review of Journalism, (February 19, 2007) Retrieved February 19, 2007

- ↑ "the iPad could finally spark demand for the hitherto unsuccessful tablet PC" --Eaton, Nick The iPad/tablet PC market defined?, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 2010

- ↑ Bright, Peter Ballmer (and Microsoft) still doesn't get the iPad, Ars Technica, 2010

- ↑ "The iPad's victory in defining the tablet: What it means". Infoworld.

- ↑ "Solipo". Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ↑ "Dolipo". Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ↑ "Polipoid". Retrieved 2014-04-21.

- ↑ Macworld.com November 11, 2006. Dan Moren. CES Unveiled@NY ‘07: Point and click coming to set-top boxes?

- ↑ Dayton, Tom. "Object-Oriented GUIs are the Future". OpenMCT Blog. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

External links

| Look up graphical user interface in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Graphical user interface. |

- Evolution of Graphical User Interface in last 50 years by Raj Lal

- The men who really invented the GUI by Clive Akass

- Graphical User Interface Gallery, screenshots of various GUIs

- Marcin Wichary's GUIdebook, Graphical User Interface gallery: over 5500 screenshots of GUI, application and icon history

- The Real History of the GUI by Mike Tuck

- In The Beginning Was The Command Line by Neal Stephenson

- 3D Graphical User Interfaces (PDF) by Farid BenHajji and Erik Dybner, Department of Computer and Systems Sciences, Stockholm University