Corona Australis

| Constellation | |

|

| |

| Abbreviation | CrA |

|---|---|

| Genitive |

|

| Pronunciation | /kəˈroʊnə ɔːˈstreɪlᵻs/ or /kəˈroʊnə ɔːˈstraɪnə/, genitive /kəˈroʊni/[1][2][3] |

| Symbolism | The Southern Crown |

| Right ascension | 17h 58m 30.1113s–19h 19m 04.7136s[4] |

| Declination | −36.7785645°–−45.5163460°[4] |

| Family | Hercules |

| Area | 128 sq. deg. (80th) |

| Main stars | 6 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 14 |

| Stars with planets | 2 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 0 |

| Brightest star | α CrA (4.10m) |

| Nearest star |

HD 166348 (42.26 ly, 12.96 pc) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | Corona Australids |

| Bordering constellations | |

|

Visible at latitudes between +40° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of August. | |

Corona Australis or Corona Austrina is a constellation in the Southern Celestial Hemisphere. Its Latin name means "southern crown", and it is the southern counterpart of Corona Borealis, the northern crown. One of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, it remains one of the 88 modern constellations. The Ancient Greeks saw Corona Australis as a wreath rather than a crown and associated it with Sagittarius or Centaurus. Other cultures have likened the pattern to a turtle, ostrich nest, a tent, or even a hut belonging to a rock hyrax.

Although fainter than its namesake, the oval- or horseshoe-shaped pattern of its brighter stars renders it distinctive. Alpha and Beta Coronae Australis are the two brightest stars with an apparent magnitude of around 4.1. Epsilon Coronae Australis is the brightest example of a W Ursae Majoris variable in the southern sky. Lying alongside the Milky Way, Corona Australis contains one of the closest star-forming regions to the Solar System—a dusty dark nebula known as the Corona Australis Molecular Cloud, lying about 430 light years away. Within it are stars at the earliest stages of their lifespan. The variable stars R and TY Coronae Australis light up parts of the nebula, which varies in brightness accordingly.

Characteristics

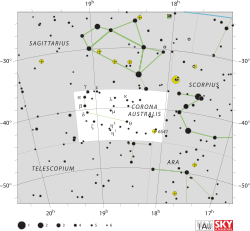

Corona Australis is a small constellation bordered by Sagittarius to the north, Scorpius to the west, Telescopium to the south, and Ara to the southwest. The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is 'CrA'.[5] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of four segments (illustrated in infobox). In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 17h 58.3m and 19h 19.0m, while the declination coordinates are between −36.77° and −45.52°.[4] Covering 128 square degrees, Corona Australis culminates at midnight around the 30th of June[6] and ranks 80th in area.[7] Only visible at latitudes south of 53° north,[7] Corona Australis cannot be seen from the British Isles as it lies too far south,[8] but it can be seen from southern Europe[9] and readily from the southern United States.[10]

Features

While not a bright constellation, Corona Australis is nonetheless distinctive due to its easily identifiable pattern of stars,[11] which has been described as horseshoe-[12] or oval-shaped.[6] Though it has no stars brighter than 4th magnitude, it still has 21 stars visible to the unaided eye (brighter than magnitude 5.5).[13] Nicolas Louis de Lacaille used the Greek letters Alpha through to Lambda to label the most prominent eleven stars in the constellation, designating two stars as Eta and omitting Iota altogether. Mu Coronae Australis, a yellow star of spectral type G5.5III and apparent magnitude 5.21,[14] was labelled by Johann Elert Bode and retained by Benjamin Gould, who deemed it bright enough to warrant naming.[15]

Stars

The only star in the constellation to have received a name is Alfecca Meridiana or Alpha CrA. The name combines the Arabic name of the constellation with the Latin for "southern".[16] In Arabic, Alfecca means "break", and refers to the shape of both Corona Australis and Corona Borealis.[17] Also called simply "Meridiana",[1] it is a white main sequence star located 130 light years away from Earth,[11] with an apparent magnitude of 4.10 and spectral type A2Va.[18] A rapidly rotating star, it spins at almost 200 km per second at its equator, making a complete revolution in around 14 hours.[19] Like the star Vega, it has excess infrared radiation, which indicates it may be ringed by a disk of dust.[17] It is currently a main-sequence star, but will eventually evolve into a white dwarf; currently, it has a luminosity 31 times greater, and a radius and mass of 2.3 times that of the Sun.[17] Beta Coronae Australis is an orange giant 510 light years from Earth.[11] Its spectral type is K0II, and it is of apparent magnitude 4.11.[20] Since its formation, it has evolved from a B-type star to a K-type star. Its luminosity class places it as a bright giant; its luminosity is 730 times that of the Sun,[21] designating it one of the highest-luminosity K0-type stars visible to the naked eye.[1] 100 million years old, it has a radius of 43 solar radii (R☉) and a mass of between 4.5 and 5 solar masses (M☉). Alpha and Beta are so similar as to be indistinguishable in brightness to the naked eye.[21]

Some of the more prominent double stars include Gamma Coronae Australis—a pair of yellowish white stars 58 light years away from Earth, which orbit each other every 122 years. Widening since 1990, the two stars can be seen as separate with a 100 mm aperture telescope;[11] they are separated by 1.3 arcseconds at an angle of 61 degrees.[22] They have a combined visual magnitude of 4.2;[23] each component is an F8V dwarf star with a magnitude of 5.01.[24][25] Epsilon Coronae Australis is an eclipsing binary belonging to a class of stars known as W Ursae Majoris variables. These star systems are known as contact binaries as the component stars are so close together they touch. Varying by a quarter of a magnitude around an average apparent magnitude of 4.83 every seven hours, the star system lies 98 light years away.[26] Its spectral type is F4VFe-0.8+.[27] At the southern end of the crown asterism are the stars Eta¹ and Eta² Coronae Australis, which form an optical double.[28] Of magnitude 5.1 and 5.5, they are separable with the naked eye and are both white.[29] Kappa Coronae Australis is an easily resolved optical double—the components are of apparent magnitudes 6.3 and 5.7 and are 1700 and 490 light years away respectively.[11] They appear at an angle of 359 degrees, separated by 21.6 arcseconds.[22] Kappa² is actually the brighter of the pair and is more bluish white,[29] with a spectral type of B9V,[30] while Kappa¹ is of spectral type A0III.[31] Lying 202 light years away, Lambda Coronae Australis is a double splittable in small telescopes. The primary is a white star of spectral type A2Vn and magnitude of 5.1,[32] while the companion star has a magnitude of 9.7.[11] The two components are separated by 29.2 arcseconds at an angle of 214 degrees.[22]

Zeta Coronae Australis is a rapidly rotating main sequence star with an apparent magnitude of 4.8, 221.7 light years from Earth. The star has blurred lines in its hydrogen spectrum due to its rotation.[28] Its spectral type is B9V.[33] Theta Coronae Australis lies further to the west, a yellow giant of spectral type G8III and apparent magnitude 4.62.[34] Corona Australis harbours RX J1856.5-3754, an isolated neutron star that is thought to lie 140 (±40) parsecs, or 460 (±130) light years, away, with a diameter of 14 km.[35] It was once suspected to be a strange star,[36] but this has been discounted.[35]

Deep sky objects

In the north of the constellation is the Corona Australis Molecular Cloud, a dark molecular cloud with many embedded reflection nebulae,[21] including NGC 6729, NGC 6726–7, and IC 4812.[37] A star-forming region of around 7000 M☉,[21] it contains Herbig–Haro objects (protostars) and some very young stars.[37] About 430 light years (130 parsecs) away, it is one of the closest star-forming regions to the Solar System.[38] The related NGC 6726 and 6727, along with unrelated NGC 6729, were first recorded by Johann Friedrich Julius Schmidt in 1865.[39] The Coronet cluster, about 554 light years (170 parsecs) away at the edge of the Gould Belt, is also used in studying star and protoplanetary disk formation.[40]

R Coronae Australis is an irregular variable star ranging from magnitudes 9.7 to 13.9.[41] Blue-white, it is of spectral type B5IIIpe.[42] A very young star, it is still accumulating interstellar material.[37] It is obscured by, and illuminates, the surrounding nebula, NGC 6729, which brightens and darkens with it.[41] The nebula is often compared to a comet for its appearance in a telescope, as its length is five times its width.[43] S Coronae Australis is a G-class dwarf in the same field as R and is a T Tauri star.[28] Nearby, another young variable star, TY Coronae Australis, illuminates another nebula: reflection nebula NGC 6726–7. TY Coronae Australis ranges irregularly between magnitudes 8.7 and 12.4,and the brightness of the nebula varies with it.[41] Blue-white, it is of spectral type B8e.[44] The largest young stars in the region, R, S, T, TY and VV Coronae Australis, are all ejecting jets of material which cause surrounding dust and gas to coalesce and form Herbig–Haro objects, many of which have been identified nearby.[45] Lying adjacent to the nebulosity is the globular cluster known as NGC 6723, which is actually in the neighbouring constellation of Sagittarius and is much much further away.[46]

Near Epsilon and Gamma Coronae Australis is Bernes 157, a dark nebula and star forming region. It is a large nebula, 55 by 18 arcminutes, that possesses several stars around magnitude 13. These stars have been dimmed by up to 8 magnitudes by its dust clouds.[47]

IC 1297 is a planetary nebula of apparent magnitude 10.7, which appears as a green-hued roundish object in higher-powered amateur instruments.[48] The nebula surrounds the variable star RU Coronae Australis, which has an average apparent magnitude of 12.9[49] and is a WC class Wolf–Rayet star.[50] IC 1297 is small, at only 7 arcseconds in diameter; it has been described as "a square with rounded edges" in the eyepiece, elongated in the north-south direction.[51] Descriptions of its color encompass blue, blue-tinged green, and green-tinged blue.[51]

Corona Australis' location near the Milky Way means that galaxies are uncommonly seen. NGC 6768 is a magnitude 11.2 object 35′ south of IC 1297. It is made up of two galaxies merging,[29] one of which is an elongated elliptical galaxy of classification E4 and the other a lenticular galaxy of classification S0.[52] IC 4808 is a galaxy of apparent magnitude 12.9 located on the border of Corona Australis with the neighbouring constellation of Telescopium and 3.9 degrees west-southwest of Beta Sagittarii. However, amateur telescopes will only show a suggestion of its spiral structure. It is 1.9 arcminutes by 0.8 arcminutes. The central area of the galaxy does appear brighter in an amateur instrument, which shows it to be tilted northeast-southwest.[53]

Southeast of Theta and southwest of Eta lies the open cluster ESO 281-SC24, which is composed of the yellow 9th magnitude star GSC 7914 178 1 and five 10th to 11th magnitude stars.[29] Halfway between Theta Coronae Australis and Theta Scorpii is the dense globular cluster NGC 6541. Described as between magnitude 6.3[41] and magnitude 6.6,[22] it is visible in binoculars and small telescopes. Around 22000 light years away, it is around 100 light years in diameter.[41] It is estimated to be around 14 billion years old.[54] NGC 6541 appears 13.1 arcminutes in diameter and is somewhat resolvable in large amateur instruments; a 12-inch telescope reveals approximately 100 stars but the core remains unresolved.[55]

Meteor showers

The Corona Australids are a meteor shower that takes place between 14 and 18 March each year, peaking around 16 March.[56] This meteor shower does not have a high peak hourly rate. In 1953 and 1956, observers noted a maximum of 6 meteors per hour and 4 meteors per hour respectively; in 1955 the shower was "barely resolved".[57] However, in 1992, astronomers detected a peak rate of 45 meteors per hour.[58] The Corona Australids' rate varies from year to year.[59][60] At only six days, the shower's duration is particularly short,[58] and its meteoroids are small; the stream is devoid of large meteoroids. The Corona Australids were first seen with the unaided eye in 1935 and first observed with radar in 1955.[60] Corona Australid meteors have an entry velocity of 45 kilometers per second.[61] In 2006, a shower originating near Beta Coronae Australis was designated as the Beta Coronae Australids. They appear in May, the same month as a nearby shower known as the May Microscopids, but the two showers have different trajectories and are unlikely to be related.[62]

History

Corona Australis may have been recorded by ancient Mesopotamians in the MUL.APIN, as a constellation called MA.GUR ("The Bark"). However, this constellation, adjacent to SUHUR.MASH ("The Goat-Fish", modern Capricornus), may instead have been modern Epsilon Sagittarii. As a part of the southern sky, MA.GUR was one of the fifteen "stars of Ea".[63]

In the 3rd century BC, the Greek didactic poet Aratus wrote of, but did not name the constellation,[64] instead calling the two crowns Στεφάνοι (Stephanoi). The Greek astronomer Ptolemy described the constellation in the 2nd century AD, though with the inclusion of Alpha Telescopii, since transferred to Telescopium.[65] Ascribing 13 stars to the constellation,[6] he named it Στεφάνος νοτιος (Stephanos notios), "Southern Wreath", while other authors associated it with either Sagittarius (having fallen off his head) or Centaurus; with the former, it was called Corona Sagittarii.[66] Similarly, the Romans called Corona Australis the "Golden Crown of Sagittarius".[67] It was known as Parvum Coelum ("Canopy", "Little Sky") in the 5th century.[68] The 18th-century French astronomer Jérôme Lalande gave it the names Sertum Australe ("Southern Garland")[66][68] and Orbiculus Capitis, while German poet and author Philippus Caesius called it Corolla ("Little Crown") or Spira Australis ("Southern Coil"), and linked it with the Crown of Eternal Life from the New Testament. Seventeenth-century celestial cartographer Julius Schiller linked it to the Diadem of Solomon.[66] Sometimes, Corona Australis was not the wreath of Sagittarius but arrows held in his hand.[68]

Corona Australis has been associated with the myth of Bacchus and Stimula. Jupiter had impregnated Stimula, causing Juno to become jealous. Juno convinced Stimula to ask Jupiter to appear in his full splendor, which the mortal woman could not handle, causing her to burn. After Bacchus, Stimula's unborn child, became an adult and the god of wine, he honored his deceased mother by placing a wreath in the sky.[69]

In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Corona Australis are located within the Black Tortoise of the North (北方玄武, Běi Fāng Xuán Wǔ).[70] The constellation itself was known as ti'en pieh ("Heavenly Turtle") and during the Western Zhou period, marked the beginning of winter. However, precession over time has meant that the "Heavenly River" (Milky Way) became the more accurate marker to the ancient Chinese and hence supplanted the turtle in this role.[71] Arabic names for Corona Australis include Al Ķubbah "the Tortoise", Al Ĥibā "the Tent" or Al Udḥā al Na'ām "the Ostrich Nest".[66][68] It was later given the name Al Iklīl al Janūbiyyah, which the European authors Chilmead, Riccioli and Caesius transliterated as Alachil Elgenubi, Elkleil Elgenubi and Aladil Algenubi respectively.[66]

The ǀXam speaking San people of South Africa knew the constellation as ≠nabbe ta !nu "house of branches"—owned originally by the Dassie (rock hyrax), and the star pattern depicting people sitting in a semicircle around a fire.[72]

The indigenous Boorong people of northwestern Victoria saw it as Won, a boomerang thrown by Totyarguil (Altair).[73] The Aranda people of Central Australia saw Corona Australis as a coolamon carrying a baby, which was accidentally dropped to earth by a group of sky-women dancing in the Milky Way. The impact of the coolamon created Gosses Bluff crater, 175 km west of Alice Springs.[74] The Torres Strait Islanders saw Corona Australis as part of a larger constellation encompassing part of Sagittarius and the tip of Scorpius's tail; the Pleiades and Orion were also associated. This constellation was Tagai's canoe, crewed by the Pleiades, called the Usiam, and Orion, called the Seg. The myth of Tagai says that he was in charge of this canoe, but his crewmen consumed all of the supplies onboard without asking permission. Enraged, Tagai bound the Usiam with a rope and tied them to the side of the boat, then threw them overboard. Scorpius's tail represents a suckerfish, while Eta Sagittarii and Theta Coronae Australis mark the bottom of the canoe.[75] On the island of Futuna, the figure of Corona Australis was called Tanuma and in the Tuamotus, it was called Na Kaua-ki-Tonga.[76]

References

- 1 2 3 Bagnall 2012, p. 170.

- ↑ "Corona". Merriam-Webster Dictionary., "Australis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary..

- ↑ "Corona Australis". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- 1 2 3 IAU, The Constellations, Corona Australis.

- ↑ Russell 1922, p. 469.

- 1 2 3 Malin & Frew 1995, p. 218

- 1 2 Ridpath, Constellations.

- ↑ Moore & Tirion 1997, p. 164

- ↑ Moore 2005, p. 202

- ↑ Moore, Stargazing 2000, p. 86

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ridpath & Tirion 2007, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Falkner 2011, p. 100

- ↑ Bakich 1995, p. 130.

- ↑ SIMBAD Mu Coronae Australis.

- ↑ Wagman 2003, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Allen 1963, pp. 172–173.

- 1 2 3 Kaler, Alfecca Meridiana.

- ↑ SIMBAD Alpha Coronae Australis.

- ↑ Royer, Zorec & Gómez 2007, p. 463.

- ↑ SIMBAD Beta Coronae Australis.

- 1 2 3 4 Kaler, Beta Coronae Australis.

- 1 2 3 4 Moore & Rees 2011, p. 413.

- ↑ SIMBAD LTT 7565.

- ↑ SIMBAD HR 7226.

- ↑ SIMBAD HR 7227.

- ↑ Kaler, Epsilon Coronae Australis.

- ↑ SIMBAD Epsilon Coronae Australis.

- 1 2 3 Motz & Nathanson 1991, pp. 254–255.

- 1 2 3 4 Streicher 2008, pp. 135–139.

- ↑ SIMBAD HR 6953.

- ↑ SIMBAD HR 6952.

- ↑ SIMBAD Lambda Coronae Australis.

- ↑ SIMBAD Zeta Coronae Australis.

- ↑ SIMBAD Theta Coronae Australis.

- 1 2 Ho Wynn C. G. et al. 2007.

- ↑ Drake, Jeremy J. et al. 2002.

- 1 2 3 Malin 2010.

- ↑ Reipurth 2008, p. 735.

- ↑ Steinicke 2010, p. 176.

- ↑ Sicilia-Aguilar, Aurora; Henning, Thomas; Juha´sz, Attila; Bouwman, Jeroen; Garmire, Gordon; Garmire, Audrey (10 November 2008). "VERY LOW MASS OBJECTS IN THE CORONET CLUSTER: THE REALM OF THE TRANSITION DISKS" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. arXiv:0807.2504

. Bibcode:2008ApJ...687.1145S. doi:10.1086/591932.

. Bibcode:2008ApJ...687.1145S. doi:10.1086/591932. - 1 2 3 4 5 O'Meara 2002, pp. 164–165, 271–273, 311

- ↑ SIMBAD R Coronae Australis.

- ↑ Bakich Podcast 25 June 2009.

- ↑ SIMBAD TY Coronae Australis.

- ↑ Wang et al. 2004.

- ↑ Coe 2007, p. 105

- ↑ Bakich 2010, p. 266.

- ↑ Griffiths 2012, p. 132

- ↑ Moore, Data Book 2000, pp. 367–368.

- ↑ SIMBAD RU Coronae Australis.

- 1 2 Bakich 2010, p. 270.

- ↑ NASA/IPAC NGC 6768.

- ↑ Bakich Podcast 18 August 2011.

- ↑ O'Meara 2011, p. 322

- ↑ Bakich Podcast 5 July 2012.

- ↑ Sherrod & Koed 2003, p. 50

- ↑ Weiss 1957, p. 300.

- 1 2 Rogers & Keay 1993, p. 274.

- ↑ Weiss 1957, p. 302.

- 1 2 Ellyett & Keay 1956, p. 479.

- ↑ Jenniskens 1994, p. 1007.

- ↑ Jopek et al. 2010, p. 871–872.

- ↑ Rogers 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ Bakich 1995, p. 83.

- ↑ Ridpath, Star Tales Corona Australis.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allen 1963, pp. 172–174.

- ↑ Simpson 2012, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 4 Motz & Nathanson 1988, p. 254.

- ↑ Staal 1988, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ AEEA 2006.

- ↑ Porter1996, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Lloyd 1873.

- ↑ Hamacher & Frew 2010.

- ↑ Hamacher 28 March 2011.

- ↑ Staal 1988, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Makemson 1941, p. 281.

Sources

- Allen, Richard Hinckley (1963) [1899]. Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning (reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-21079-7.

- Bagnall, Philip M. (2012). The Star Atlas Companion : What you need to know about the Constellations. Springer New York. ISBN 978-1-4614-0830-7.

- Bakich, Michael E. (1995). The Cambridge Guide to the Constellations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44921-2.

- Bakich, Michael E. (2010). 1,001 Celestial Wonders to See Before You Die. Springer Science + Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-1777-5.

- Coe, Steven R. (2007). Nebulae and how to observe them. Astronomers' observing guides. New York, New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-84628-482-3.

- Drake, Jeremy J.; Marshall, Herman L.; Dreizler, Stefan; Freeman, Peter E.; Fruscione, Antonella; Juda, Michael; Kashyap, Vinay; Nicastro, Fabrizio; Pease, Deron O.; Wargelin, Bradford J.; Werner, Klaus (June 2002). "Is RX J1856.5−3754 a Quark Star?". The Astrophysical Journal. 572 (2): 996–1001. arXiv:astro-ph/0204159

. Bibcode:2002ApJ...572..996D. doi:10.1086/340368.

. Bibcode:2002ApJ...572..996D. doi:10.1086/340368. - Ellyett, C. D.; Keay, C. S. L. (1956). "Radio Echo Observations of Meteor Activity in the Southern Hemisphere" (PDF). Australian Journal of Physics. 9 (4): 471–480. Bibcode:1956AuJPh...9..471E. doi:10.1071/PH560471.

- Falkner, David E. (2011). The Mythology of the Night Sky: An Amateur Astronomer's Guide to the Ancient Greek and Roman Legends. New York, New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-0136-0.

- Griffiths, Martin (2012). Planetary Nebulae and How to Observe Them. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-1781-1.

- Hamacher, Duane W.; Frew, David J. (2010). "An Aboriginal Australian Record of the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae" (PDF). Journal of Astronomical History & Heritage. 13 (3): 220–234. arXiv:1010.4610

. Bibcode:2010JAHH...13..220H.

. Bibcode:2010JAHH...13..220H. - Ho, W. C. G.; Kaplan, D. L.; Chang, P.; Van Adelsberg, M.; Potekhin, A. Y. (March 2007). "Magnetic hydrogen atmosphere models and the neutron star RX J1856.5–3754". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 375 (3): 821–830. arXiv:astro-ph/0612145v1

. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.375..821H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11376.x.

. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.375..821H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11376.x. - Jenniskens, Peter (July 1994). "Meteor stream activity I. The annual streams". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 287: 990–1013. Bibcode:1994A&A...287..990J.

- Jopek, T. J.; Koten, P.; Pecina, P. (May 2010). "Meteoroid streams identification amongst 231 Southern hemisphere video meteors". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 404 (2): 867–875. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.404..867J. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.16316.x.

- Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941). The Morning Star Rises: an account of Polynesian astronomy. Yale University Press.

- Malin, David; Frew, David J. (1995). Hartung's Astronomical Objects for Southern Telescopes: A Handbook for Amateur Observers. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55491-6.

- Malin, David (August 2010). "The Corona Australis nebula (NGC 6726-27-29)". Australian Astronomical Observatory. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Moore, Patrick; Tirion, Wil (1997). Cambridge Guide to Stars and Planets. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58582-8.

- Moore, Patrick (2000). The Data Book of Astronomy. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7503-0620-1.

- Moore, Patrick (2000). Stargazing: Astronomy without a Telescope. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79445-9.

- Moore, Patrick (2005). The Observer's Year: 366 Nights of the Universe. Springer. ISBN 978-1-85233-884-8.

- Moore, Patrick; Rees, Robin (2011). Patrick Moore's Data Book of Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-04070-9.

- Motz, Lloyd; Nathanson, Carol (1988). The Constellations. New York City: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-17600-2.

- Motz, Lloyd; Nathanson, Carol (1991). The Constellations: An Enthusiast's Guide to the Night Sky. London, United Kingdom: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-85410-088-7.

- O'Meara, Stephen James (2002). The Caldwell Objects. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82796-6.

- O'Meara, Stephen James (2011). Deep-Sky Companions: The Secret Deep. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19876-9.

- Porter, Deborah Lynn (1996). From Deluge to Discourse: Myth, History, and the Generation of Chinese Fiction. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3034-7.

- Reipurth, Bo, ed. (2008). "The Corona Australis Star Forming Region". Handbook of Star Forming Regions. II: The Southern Sky. ASP Monograph Publications. Bibcode:2008hsf2.book..735N.

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2007). Stars and Planets Guide. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

- Rogers, J. H. (1998). "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (1): 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- Rogers, L. J.; Keay, C. S. L. (1993). Stohl, J.; Williams, I.P., eds. "Observations of some southern hemisphere meteor showers". Meteoroids and their parent bodies, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Symposium held at Smolenice, Slovakia, July 6–12, 1992: 273–276. Bibcode:1993mtpb.conf..273R.

- Royer, F.; Zorec, J.; Gómez, A.E. (February 2007). "Rotational velocities of A-type stars. III. Velocity distributions" (PDF). 463 (2). Astronomy and Astrophysics: 671–682. arXiv:astro-ph/0610785

. Bibcode:2007A&A...463..671R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065224.

. Bibcode:2007A&A...463..671R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065224. - Russell, Henry Norris (October 1922). "The new international symbols for the constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- Sherrod, P. Clay; Koed, Thomas L. (2003). A Complete Manual of Amateur Astronomy: Tools and Techniques for Astronomical Observations. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-42820-8.

- Simpson, Phil (2012). Guidebook to the Constellations : Telescopic Sights, Tales, and Myths. Springer New York. ISBN 978-1-4419-6940-8.

- Staal, Julius D. W. (1988). The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars. McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-04-5.

- Steinicke, Wolfgang (2010). Observing and Cataloging Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19267-5.

- Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, VA: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- Wang, Hongchi; Mundt, Reinhard; Henning, Thomas; Apai, Dániel (20 December 2004). "Optical Outflows in the R Coronae Australis Molecular Cloud" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 617 (2): 1191–1203. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617.1191W. doi:10.1086/425493.

- Weiss, A. A. (1957). "Meteor Activity in the Southern Hemisphere". Australian Journal of Physics. 10 (2): 299–308. Bibcode:1957AuJPh..10..299W. doi:10.1071/PH570299.

Online sources

- "AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 7 月 2 日" (in Chinese). 2006. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- Bakich, Michael E. (25 June 2009). "Podcast: Night-sky targets for June 26 – July 3, 2009". Astronomy. Retrieved 21 August 2012. (subscription required)

- Bakich, Michael E. (26 August 2010). "Observing podcast: Corona Australis, the Castaway Cluster, and the Red Spider Nebula". Retrieved 21 August 2012. (subscription required)

- Bakich, Michael E. (18 August 2011). "Open cluster M26, globular cluster M56, and spiral galaxy IC 4808". Astronomy. Retrieved 21 August 2012. (subscription required)

- Bakich, Michael E. (5 July 2012). "Globular cluster NGC 6541, planetary nebula NGC 6563, and irregular galaxy IC 4662". Astronomy. Retrieved 21 August 2012. (subscription required)

- Hamacher, Duane (28 March 2011). "Impact Craters in Aboriginal Dreamings, Part 2: Tnorala (Gosses Bluff)". Australian Aboriginal Astronomy. Aboriginal Astronomy Project. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- "Corona Australis, constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Kaler, Jim. "Alfecca Meridiana". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- Kaler, Jim. "Beta Coronae Australis". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- Kaler, Jim. "Epsilon Coronae Australis". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2011). "Classifications for NGC 6768: 2 Classifications found in NED". NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database. California Institute of Technology/National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Lloyd, Lucy (11 October 1873). "Story: ≠nabbe ta !nu (Corona Australis)". The Digital Bleek & Lloyd. University of Cape Town. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations". Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Corona Australis". Star Tales. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Streicher, Magda (August 2008). "The Southern Queen's Crown" (PDF). Deepsky Delights. The Astronomical Society of Southern Africa. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Alpha Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- "Beta Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- "LTT 7565 (Gamma Coronae Australis)". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- "HR 7226 (Gamma Coronae Australis A)". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- "HR 7227 (Gamma Coronae Australis B)". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- "Epsilon Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- "HR 6953 (Kappa² Coronae Australis)". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "HR 6952 (Kappa¹ Coronae Australis)". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Lambda Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "HR 7050 (Mu Coronae Australis)". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Zeta Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- "Theta Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- "R Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- "TY Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "RU Coronae Australis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Corona Australis

- Corona Australis photo

- Corona Australis at Constellation Guide

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (over 30 medieval and early modern images of Corona Australis)

Coordinates: ![]() 19h 00m 00s, −40° 00′ 00″

19h 00m 00s, −40° 00′ 00″