Hales Bar Dam

|

Hale's Bar Dam Powerhouse | |

|

Hales Bar Dam Powerhouse, now used as dry boat storage for Hales Bar Marina | |

| |

| Location | 1265 Hale's Bar Rd., Haletown, Tennessee |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°2′48″N 85°32′22″W / 35.04667°N 85.53944°WCoordinates: 35°2′48″N 85°32′22″W / 35.04667°N 85.53944°W |

| Area | 2 acres (0.81 ha) |

| Built | 1913 |

| Architect | John Bogart[1] |

| Architectural style | Classical Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 08001111[2] |

| Added to NRHP | November 25, 2008 |

Hales Bar Dam was a hydroelectric dam once located on the Tennessee River in Marion County, Tennessee, United States. The Chattanooga and Tennessee River Power Company began building the dam in 1905 and completed it in 1913, making Hales Bar one of the first major multipurpose dams and one of the first major dams to be built across a navigable channel in the United States.

In 1939, the Tennessee Valley Authority assumed control of Hales Bar Dam after purchasing TEPCO's assets. TVA spent two decades trying to fix a leakage problem that had plagued Hales Bar since its construction, but after continued leakage, and after it was determined that expanding the dam's navigation lock would be too expensive, TVA decided to replace the dam by building Nickajack Dam 6 miles (9.7 km) downstream in 1968.[3]

Location and capacity

Hales Bar Dam was located along the Tennessee River at just over 431 miles (694 km) above the river's mouth, near the southwest end of the Tennessee River Gorge. The dam's reservoir extended up the river through the gorge all the way to Chattanooga, and had 162 miles (261 km) of shoreline. Before the construction of Hales Bar, this was a particularly unpredictable and dangerous section of the river, with numerous navigation obstacles. Downstream from the dam site, the river begins to steady as it enters the hills and flatlands near Guntersville.

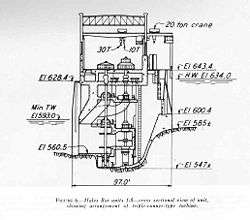

Hales Bar Dam was 113 feet (34 m) high and 2,315 feet (706 m) long, and its spillway had a combined discharge capacity of 224,000 cubic feet per second (6,300 m3/s). After improvements by TVA in 1949, the dam had a generating capacity of 99,700 kilowatts. The dam's lock, which went into operation on November 1, 1913, was 60 feet (18 m) by 260 feet (79 m), and its 41-foot (12 m) lift was the highest in the world at that time.[3][4]

Construction

Along with Muscle Shoals and the Elk River Shoals further downstream, the Tennessee River Gorge had long been one of the major impediments to river navigation in the upper Tennessee Valley. While various 19th-century canal projects had minor success in extending navigation across the shoals, the Tennessee River Gorge remained largely untamed. In 1898, several Chattanooga business interests formed the Tennessee River Improvement Association to lobby for efforts to extend year-round navigation to Chattanooga, and around 1900, Major Dan C. Kingman of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers drafted a design for a dam that would flood the Tennessee River Gorge and remove the swift current and various hazards that had long prevented large-scale navigation through this stretch of the river. In 1904, Kingman's friend, Josephus Conn Guild, offered to build the dam with private funding in exchange for the rights to the dam's hydroelectric power. Congress passed the enabling legislation on April 27, 1904, and with funding from Chattanooga entrepreneur Charles E. James and New York financier Anthony Brady, Guild formed the Chattanooga and Tennessee River Power Company to oversee the project.[5]

The dam's initial contractor, William J. Oliver and Company, began work on the dam in October 1905. Two self-contained communities, Guild (now Haletown) and Ladds, were built to house the thousands of construction workers needed to build the dam. The dam was originally slated for completion in 1909, but numerous difficulties brought about primarily by the soft bedrock upon which the dam was built continuously stalled construction, and by 1910, only the lock and powerhouse had been completed. Engineers finally began to make progress after employing the use of pressure grouting and concrete caissons— the first use of either in a major dam construction project— and Hales Bar Dam was finished on November 11, 1913. Leaks began to appear almost immediately after completion, however. In 1919, engineers attempted to minimize the leakage by pumping hot asphalt into the dam's foundation. This was temporarily successful, but by 1931, a study showed the dam was leaking at a rate of 1,000 cubic feet per second (28 m3/s).[3]

TVA operations

The passage of the TVA Act in 1933 created the Tennessee Valley Authority and gave it control of flood control and improvement initiatives in the Tennessee Valley. By this time, Chattanooga and Tennessee River Power had merged with several other companies to form the Tennessee Electric Power Company, or TEPCO. The new company was eventually headed by Guild's son, Jo Conn Guild, who was a fierce opponent of TVA. With the help of attorney Wendell Willkie, TEPCO challenged the constitutionality of the TVA Act in federal court. In 1939, however, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Tennessee Electric Power Company v. TVA in which they upheld the TVA Act, and a few months later, TEPCO was forced to sell most of its assets, including Hales Bar Dam, to TVA for $78 million.[6]

After gaining control of Hales Bar Dam in 1939, TVA carried out extensive repair work on the dam's foundation that by 1943 had succeeded in halting the dam's leakage. In 1949, TVA increased the dam's generating capacity and equipped the spillway with radial gates that helped extend the Hales Bar Reservoir's navigation channel all the way to the base of Chickamauga Dam. In the late 1950s, however, boils began to appear in the water below Hales Bar Dam, and an investigation showed the dam was again leaking, this time at an alarming 2,000 cubic feet per second (57 m3/s). Dye tests carried out in 1960 suggested that many of the leakage channels had interconnected, increasing the possibility of a future dam failure.[3]

In the 1960s, TVA began expanding the size of its dam locks to accommodate the increase in river traffic the Tennessee Valley had experienced since the end of World War II. A study in 1963 suggested that expanding the size of the Hales Bar lock would be extremely expensive, and considering the continued expenses involved with leak repair, TVA decided that would be more practical to replace the dam altogether. Nickajack Dam was authorized in January 1963 and construction was completed December 14, 1967. Operations were halted at Hales Bar Dam the following day, and by September 1968, Hales Bar Dam had been dismantled to the extent that it no longer threatened navigation on the new Nickajack Lake. Two of Hales Bar's generators and parts of Hales Bar's switchyard were installed at Nickajack.[3]

References

- ↑ Paul Archambault. National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Hale's Bar Dam Powerhouse. National Park Service, 2008-05-30. Accessed 2009-08-31.

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tennessee Valley Authority, The Nickajack Project: A Report on the Planning, Design, Construction, Initial Operations, and Costs, Technical Report No. 16 (Knoxville, Tenn.: Tennessee Valley Authority, 1972), pp. 1-3, 10-11, 17-19, 307-311.

- ↑ Tennessee Valley Authority, The Melton Hill Project: A Report on the Planning, Design, Construction, Initial Operations, and Costs, Technical Report No. 15 (Knoxville, Tenn.: Tennessee Valley Authority, 1966), pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Gilbert Govan and James Livingood, The Chattanooga Country, 1540-1962: From Tomahawks to TVA (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1963), pp. 445-447.

- ↑ Timothy Ezzell, "Jo Conn Guild." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 14 January 2009.

External links

- Hales Bar Marina and Resort — resort presently located at the site of Hales Bar Dam