Hash table

| Hash table | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Unordered associative array | |

| Invented | 1953 | |

| Time complexity in big O notation | ||

| Average | Worst case | |

| Space | O(n)[1] | O(n) |

| Search | O(1) | O(n) |

| Insert | O(1) | O(n) |

| Delete | O(1) | O(n) |

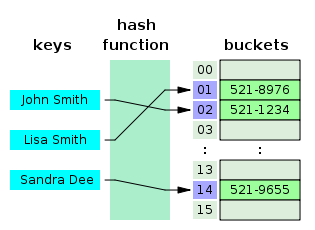

In computing, a hash table (hash map) is a data structure used to implement an associative array, a structure that can map keys to values. A hash table uses a hash function to compute an index into an array of buckets or slots, from which the desired value can be found.

Ideally, the hash function will assign each key to a unique bucket, but most hash table designs employ an imperfect hash function, which might cause hash collisions where the hash function generates the same index for more than one key. Such collisions must be accommodated in some way.

In a well-dimensioned hash table, the average cost (number of instructions) for each lookup is independent of the number of elements stored in the table. Many hash table designs also allow arbitrary insertions and deletions of key-value pairs, at (amortized[2]) constant average cost per operation.[3][4]

In many situations, hash tables turn out to be more efficient than search trees or any other table lookup structure. For this reason, they are widely used in many kinds of computer software, particularly for associative arrays, database indexing, caches, and sets.

Hashing

The idea of hashing is to distribute the entries (key/value pairs) across an array of buckets. Given a key, the algorithm computes an index that suggests where the entry can be found:

index = f(key, array_size)

Often this is done in two steps:

hash = hashfunc(key) index = hash % array_size

In this method, the hash is independent of the array size, and it is then reduced to an index (a number between 0 and array_size − 1) using the modulo operator (%).

In the case that the array size is a power of two, the remainder operation is reduced to masking, which improves speed, but can increase problems with a poor hash function.

Choosing a good hash function

A good hash function and implementation algorithm are essential for good hash table performance, but may be difficult to achieve.

A basic requirement is that the function should provide a uniform distribution of hash values. A non-uniform distribution increases the number of collisions and the cost of resolving them. Uniformity is sometimes difficult to ensure by design, but may be evaluated empirically using statistical tests, e.g., a Pearson's chi-squared test for discrete uniform distributions.[5][6]

The distribution needs to be uniform only for table sizes that occur in the application. In particular, if one uses dynamic resizing with exact doubling and halving of the table size s, then the hash function needs to be uniform only when s is a power of two. Here the index can be computed as some range of bits of the hash function. On the other hand, some hashing algorithms prefer to have s be a prime number.[7] The modulus operation may provide some additional mixing; this is especially useful with a poor hash function.

For open addressing schemes, the hash function should also avoid clustering, the mapping of two or more keys to consecutive slots. Such clustering may cause the lookup cost to skyrocket, even if the load factor is low and collisions are infrequent. The popular multiplicative hash[3] is claimed to have particularly poor clustering behavior.[7]

Cryptographic hash functions are believed to provide good hash functions for any table size s, either by modulo reduction or by bit masking. They may also be appropriate if there is a risk of malicious users trying to sabotage a network service by submitting requests designed to generate a large number of collisions in the server's hash tables. However, the risk of sabotage can also be avoided by cheaper methods (such as applying a secret salt to the data, or using a universal hash function). A drawback of cryptographic hashing functions is that they are often slower to compute, which means that in cases where the uniformity for any s is not necessary, a non-cryptographic hashing function might be preferable.

Perfect hash function

If all keys are known ahead of time, a perfect hash function can be used to create a perfect hash table that has no collisions. If minimal perfect hashing is used, every location in the hash table can be used as well.

Perfect hashing allows for constant time lookups in all cases. This is in contrast to most chaining and open addressing methods, where the time for lookup is low on average, but may be very large, O(n), for some sets of keys.

Key statistics

A critical statistic for a hash table is the load factor, defined as

where

- n is the number of entries;

- k is the number of buckets.

As the load factor grows larger, the hash table becomes slower, and it may even fail to work (depending on the method used). The expected constant time property of a hash table assumes that the load factor is kept below some bound. For a fixed number of buckets, the time for a lookup grows with the number of entries and therefore the desired constant time is not achieved.

Second to that, one can examine the variance of number of entries per bucket. For example, two tables both have 1,000 entries and 1,000 buckets; one has exactly one entry in each bucket, the other has all entries in the same bucket. Clearly the hashing is not working in the second one.

A low load factor is not especially beneficial. As the load factor approaches 0, the proportion of unused areas in the hash table increases, but there is not necessarily any reduction in search cost. This results in wasted memory.

Collision resolution

Hash collisions are practically unavoidable when hashing a random subset of a large set of possible keys. For example, if 2,450 keys are hashed into a million buckets, even with a perfectly uniform random distribution, according to the birthday problem there is approximately a 95% chance of at least two of the keys being hashed to the same slot.

Therefore, almost all hash table implementations have some collision resolution strategy to handle such events. Some common strategies are described below. All these methods require that the keys (or pointers to them) be stored in the table, together with the associated values.

Separate chaining

In the method known as separate chaining, each bucket is independent, and has some sort of list of entries with the same index. The time for hash table operations is the time to find the bucket (which is constant) plus the time for the list operation.

In a good hash table, each bucket has zero or one entries, and sometimes two or three, but rarely more than that. Therefore, structures that are efficient in time and space for these cases are preferred. Structures that are efficient for a fairly large number of entries per bucket are not needed or desirable. If these cases happen often, the hashing function needs to be fixed.

Separate chaining with linked lists

Chained hash tables with linked lists are popular because they require only basic data structures with simple algorithms, and can use simple hash functions that are unsuitable for other methods.

The cost of a table operation is that of scanning the entries of the selected bucket for the desired key. If the distribution of keys is sufficiently uniform, the average cost of a lookup depends only on the average number of keys per bucket—that is, it is roughly proportional to the load factor.

For this reason, chained hash tables remain effective even when the number of table entries n is much higher than the number of slots. For example, a chained hash table with 1000 slots and 10,000 stored keys (load factor 10) is five to ten times slower than a 10,000-slot table (load factor 1); but still 1000 times faster than a plain sequential list.

For separate-chaining, the worst-case scenario is when all entries are inserted into the same bucket, in which case the hash table is ineffective and the cost is that of searching the bucket data structure. If the latter is a linear list, the lookup procedure may have to scan all its entries, so the worst-case cost is proportional to the number n of entries in the table.

The bucket chains are often searched sequentially using the order the entries were added to the bucket. If the load factor is large and some keys are more likely to come up than others, then rearranging the chain with a move-to-front heuristic may be effective. More sophisticated data structures, such as balanced search trees, are worth considering only if the load factor is large (about 10 or more), or if the hash distribution is likely to be very non-uniform, or if one must guarantee good performance even in a worst-case scenario. However, using a larger table and/or a better hash function may be even more effective in those cases.

Chained hash tables also inherit the disadvantages of linked lists. When storing small keys and values, the space overhead of the next pointer in each entry record can be significant. An additional disadvantage is that traversing a linked list has poor cache performance, making the processor cache ineffective.

Separate chaining with list head cells

Some chaining implementations store the first record of each chain in the slot array itself.[4] The number of pointer traversals is decreased by one for most cases. The purpose is to increase cache efficiency of hash table access.

The disadvantage is that an empty bucket takes the same space as a bucket with one entry. To save space, such hash tables often have about as many slots as stored entries, meaning that many slots have two or more entries.

Separate chaining with other structures

Instead of a list, one can use any other data structure that supports the required operations. For example, by using a self-balancing binary search tree, the theoretical worst-case time of common hash table operations (insertion, deletion, lookup) can be brought down to O(log n) rather than O(n). However, this introduces extra complexity into the implementation, and may cause even worse performance for smaller hash tables, where the time spent inserting into and balancing the tree is greater than the time needed to perform a linear search on all of the elements of a list.[3][8] A real world example of a hash table that uses a self-balancing binary search tree for buckets is the HashMap class in Java version 8.[9]

The variant called array hash table uses a dynamic array to store all the entries that hash to the same slot.[10][11][12] Each newly inserted entry gets appended to the end of the dynamic array that is assigned to the slot. The dynamic array is resized in an exact-fit manner, meaning it is grown only by as many bytes as needed. Alternative techniques such as growing the array by block sizes or pages were found to improve insertion performance, but at a cost in space. This variation makes more efficient use of CPU caching and the translation lookaside buffer (TLB), because slot entries are stored in sequential memory positions. It also dispenses with the next pointers that are required by linked lists, which saves space. Despite frequent array resizing, space overheads incurred by the operating system such as memory fragmentation were found to be small.

An elaboration on this approach is the so-called dynamic perfect hashing,[13] where a bucket that contains k entries is organized as a perfect hash table with k2 slots. While it uses more memory (n2 slots for n entries, in the worst case and n × k slots in the average case), this variant has guaranteed constant worst-case lookup time, and low amortized time for insertion. It is also possible to use a fusion tree for each bucket, achieving constant time for all operations with high probability.[14]

Open addressing

In another strategy, called open addressing, all entry records are stored in the bucket array itself. When a new entry has to be inserted, the buckets are examined, starting with the hashed-to slot and proceeding in some probe sequence, until an unoccupied slot is found. When searching for an entry, the buckets are scanned in the same sequence, until either the target record is found, or an unused array slot is found, which indicates that there is no such key in the table.[15] The name "open addressing" refers to the fact that the location ("address") of the item is not determined by its hash value. (This method is also called closed hashing; it should not be confused with "open hashing" or "closed addressing" that usually mean separate chaining.)

Well-known probe sequences include:

- Linear probing, in which the interval between probes is fixed (usually 1)

- Quadratic probing, in which the interval between probes is increased by adding the successive outputs of a quadratic polynomial to the starting value given by the original hash computation

- Double hashing, in which the interval between probes is computed by a second hash function

A drawback of all these open addressing schemes is that the number of stored entries cannot exceed the number of slots in the bucket array. In fact, even with good hash functions, their performance dramatically degrades when the load factor grows beyond 0.7 or so. For many applications, these restrictions mandate the use of dynamic resizing, with its attendant costs.

Open addressing schemes also put more stringent requirements on the hash function: besides distributing the keys more uniformly over the buckets, the function must also minimize the clustering of hash values that are consecutive in the probe order. Using separate chaining, the only concern is that too many objects map to the same hash value; whether they are adjacent or nearby is completely irrelevant.

Open addressing only saves memory if the entries are small (less than four times the size of a pointer) and the load factor is not too small. If the load factor is close to zero (that is, there are far more buckets than stored entries), open addressing is wasteful even if each entry is just two words.

Open addressing avoids the time overhead of allocating each new entry record, and can be implemented even in the absence of a memory allocator. It also avoids the extra indirection required to access the first entry of each bucket (that is, usually the only one). It also has better locality of reference, particularly with linear probing. With small record sizes, these factors can yield better performance than chaining, particularly for lookups. Hash tables with open addressing are also easier to serialize, because they do not use pointers.

On the other hand, normal open addressing is a poor choice for large elements, because these elements fill entire CPU cache lines (negating the cache advantage), and a large amount of space is wasted on large empty table slots. If the open addressing table only stores references to elements (external storage), it uses space comparable to chaining even for large records but loses its speed advantage.

Generally speaking, open addressing is better used for hash tables with small records that can be stored within the table (internal storage) and fit in a cache line. They are particularly suitable for elements of one word or less. If the table is expected to have a high load factor, the records are large, or the data is variable-sized, chained hash tables often perform as well or better.

Ultimately, used sensibly, any kind of hash table algorithm is usually fast enough; and the percentage of a calculation spent in hash table code is low. Memory usage is rarely considered excessive. Therefore, in most cases the differences between these algorithms are marginal, and other considerations typically come into play.

Coalesced hashing

A hybrid of chaining and open addressing, coalesced hashing links together chains of nodes within the table itself.[15] Like open addressing, it achieves space usage and (somewhat diminished) cache advantages over chaining. Like chaining, it does not exhibit clustering effects; in fact, the table can be efficiently filled to a high density. Unlike chaining, it cannot have more elements than table slots.

Cuckoo hashing

Another alternative open-addressing solution is cuckoo hashing, which ensures constant lookup time in the worst case, and constant amortized time for insertions and deletions. It uses two or more hash functions, which means any key/value pair could be in two or more locations. For lookup, the first hash function is used; if the key/value is not found, then the second hash function is used, and so on. If a collision happens during insertion, then the key is re-hashed with the second hash function to map it to another bucket. If all hash functions are used and there is still a collision, then the key it collided with is removed to make space for the new key, and the old key is re-hashed with one of the other hash functions, which maps it to another bucket. If that location also results in a collision, then the process repeats until there is no collision or the process traverses all the buckets, at which point the table is resized. By combining multiple hash functions with multiple cells per bucket, very high space utilization can be achieved.

Hopscotch hashing

Another alternative open-addressing solution is hopscotch hashing,[16] which combines the approaches of cuckoo hashing and linear probing, yet seems in general to avoid their limitations. In particular it works well even when the load factor grows beyond 0.9. The algorithm is well suited for implementing a resizable concurrent hash table.

The hopscotch hashing algorithm works by defining a neighborhood of buckets near the original hashed bucket, where a given entry is always found. Thus, search is limited to the number of entries in this neighborhood, which is logarithmic in the worst case, constant on average, and with proper alignment of the neighborhood typically requires one cache miss. When inserting an entry, one first attempts to add it to a bucket in the neighborhood. However, if all buckets in this neighborhood are occupied, the algorithm traverses buckets in sequence until an open slot (an unoccupied bucket) is found (as in linear probing). At that point, since the empty bucket is outside the neighborhood, items are repeatedly displaced in a sequence of hops. (This is similar to cuckoo hashing, but with the difference that in this case the empty slot is being moved into the neighborhood, instead of items being moved out with the hope of eventually finding an empty slot.) Each hop brings the open slot closer to the original neighborhood, without invalidating the neighborhood property of any of the buckets along the way. In the end, the open slot has been moved into the neighborhood, and the entry being inserted can be added to it.

Robin Hood hashing

One interesting variation on double-hashing collision resolution is Robin Hood hashing.[17][18] The idea is that a new key may displace a key already inserted, if its probe count is larger than that of the key at the current position. The net effect of this is that it reduces worst case search times in the table. This is similar to ordered hash tables[19] except that the criterion for bumping a key does not depend on a direct relationship between the keys. Since both the worst case and the variation in the number of probes is reduced dramatically, an interesting variation is to probe the table starting at the expected successful probe value and then expand from that position in both directions.[20] External Robin Hood hashing is an extension of this algorithm where the table is stored in an external file and each table position corresponds to a fixed-sized page or bucket with B records.[21]

2-choice hashing

2-choice hashing employs two different hash functions, h1(x) and h2(x), for the hash table. Both hash functions are used to compute two table locations. When an object is inserted in the table, then it is placed in the table location that contains fewer objects (with the default being the h1(x) table location if there is equality in bucket size). 2-choice hashing employs the principle of the power of two choices.[22]

Dynamic resizing

The good functioning of a hash table depends on the fact that the table size is proportional to the number of entries. With a fixed size, and the common structures, it is similar to linear search, except with a better constant factor. In some cases, the number of entries may be definitely known in advance, for example keywords in a language. More commonly, this is not known for sure, if only due to later changes in code and data. It is one serious, although common, mistake to not provide any way for the table to resize. A general-purpose hash table "class" will almost always have some way to resize, and it is good practice even for simple "custom" tables. An implementation should check the load factor, and do something if it becomes too large (this needs to be done only on inserts, since that is the only thing that would increase it).

To keep the load factor under a certain limit, e.g., under 3/4, many table implementations expand the table when items are inserted. For example, in Java's HashMap class the default load factor threshold for table expansion is 3/4 and in Python's dict, table size is resized when load factor is greater than 2/3.

Since buckets are usually implemented on top of a dynamic array and any constant proportion for resizing greater than 1 will keep the load factor under the desired limit, the exact choice of the constant is determined by the same space-time tradeoff as for dynamic arrays.

Resizing is accompanied by a full or incremental table rehash whereby existing items are mapped to new bucket locations.

To limit the proportion of memory wasted due to empty buckets, some implementations also shrink the size of the table—followed by a rehash—when items are deleted. From the point of space-time tradeoffs, this operation is similar to the deallocation in dynamic arrays.

Resizing by copying all entries

A common approach is to automatically trigger a complete resizing when the load factor exceeds some threshold rmax. Then a new larger table is allocated, each entry is removed from the old table, and inserted into the new table. When all entries have been removed from the old table then the old table is returned to the free storage pool. Symmetrically, when the load factor falls below a second threshold rmin, all entries are moved to a new smaller table.

For hash tables that shrink and grow frequently, the resizing downward can be skipped entirely. In this case, the table size is proportional to the maximum number of entries that ever were in the hash table at one time, rather than the current number. The disadvantage is that memory usage will be higher, and thus cache behavior may be worse. For best control, a "shrink-to-fit" operation can be provided that does this only on request.

If the table size increases or decreases by a fixed percentage at each expansion, the total cost of these resizings, amortized over all insert and delete operations, is still a constant, independent of the number of entries n and of the number m of operations performed.

For example, consider a table that was created with the minimum possible size and is doubled each time the load ratio exceeds some threshold. If m elements are inserted into that table, the total number of extra re-insertions that occur in all dynamic resizings of the table is at most m − 1. In other words, dynamic resizing roughly doubles the cost of each insert or delete operation.

Incremental resizing

Some hash table implementations, notably in real-time systems, cannot pay the price of enlarging the hash table all at once, because it may interrupt time-critical operations. If one cannot avoid dynamic resizing, a solution is to perform the resizing gradually:

- During the resize, allocate the new hash table, but keep the old table unchanged.

- In each lookup or delete operation, check both tables.

- Perform insertion operations only in the new table.

- At each insertion also move r elements from the old table to the new table.

- When all elements are removed from the old table, deallocate it.

To ensure that the old table is completely copied over before the new table itself needs to be enlarged, it is necessary to increase the size of the table by a factor of at least (r + 1)/r during resizing.

Disk-based hash tables almost always use some scheme of incremental resizing, since the cost of rebuilding the entire table on disk would be too high.

Monotonic keys

If it is known that key values will always increase (or decrease) monotonically, then a variation of consistent hashing can be achieved by keeping a list of the single most recent key value at each hash table resize operation. Upon lookup, keys that fall in the ranges defined by these list entries are directed to the appropriate hash function—and indeed hash table—both of which can be different for each range. Since it is common to grow the overall number of entries by doubling, there will only be O(log(N)) ranges to check, and binary search time for the redirection would be O(log(log(N))). As with consistent hashing, this approach guarantees that any key's hash, once issued, will never change, even when the hash table is later grown.

Other solutions

Linear hashing[23] is a hash table algorithm that permits incremental hash table expansion. It is implemented using a single hash table, but with two possible lookup functions.

Another way to decrease the cost of table resizing is to choose a hash function in such a way that the hashes of most values do not change when the table is resized. Such hash functions are prevalent in disk-based and distributed hash tables, where rehashing is prohibitively costly. The problem of designing a hash such that most values do not change when the table is resized is known as the distributed hash table problem. The four most popular approaches are rendezvous hashing, consistent hashing, the content addressable network algorithm, and Kademlia distance.

Performance analysis

In the simplest model, the hash function is completely unspecified and the table does not resize. For the best possible choice of hash function, a table of size k with open addressing has no collisions and holds up to k elements, with a single comparison for successful lookup, and a table of size k with chaining and n keys has the minimum max(0, n − k) collisions and O(1 + n/k) comparisons for lookup. For the worst choice of hash function, every insertion causes a collision, and hash tables degenerate to linear search, with Ω(n) amortized comparisons per insertion and up to n comparisons for a successful lookup.

Adding rehashing to this model is straightforward. As in a dynamic array, geometric resizing by a factor of b implies that only n/bi keys are inserted i or more times, so that the total number of insertions is bounded above by bn/(b − 1), which is O(n). By using rehashing to maintain n < k, tables using both chaining and open addressing can have unlimited elements and perform successful lookup in a single comparison for the best choice of hash function.

In more realistic models, the hash function is a random variable over a probability distribution of hash functions, and performance is computed on average over the choice of hash function. When this distribution is uniform, the assumption is called "simple uniform hashing" and it can be shown that hashing with chaining requires Θ(1 + n/k) comparisons on average for an unsuccessful lookup, and hashing with open addressing requires Θ(1/(1 − n/k)).[24] Both these bounds are constant, if we maintain n/k < c using table resizing, where c is a fixed constant less than 1.

Features

Advantages

The main advantage of hash tables over other table data structures is speed. This advantage is more apparent when the number of entries is large. Hash tables are particularly efficient when the maximum number of entries can be predicted in advance, so that the bucket array can be allocated once with the optimum size and never resized.

If the set of key-value pairs is fixed and known ahead of time (so insertions and deletions are not allowed), one may reduce the average lookup cost by a careful choice of the hash function, bucket table size, and internal data structures. In particular, one may be able to devise a hash function that is collision-free, or even perfect (see below). In this case the keys need not be stored in the table.

Drawbacks

Although operations on a hash table take constant time on average, the cost of a good hash function can be significantly higher than the inner loop of the lookup algorithm for a sequential list or search tree. Thus hash tables are not effective when the number of entries is very small. (However, in some cases the high cost of computing the hash function can be mitigated by saving the hash value together with the key.)

For certain string processing applications, such as spell-checking, hash tables may be less efficient than tries, finite automata, or Judy arrays. Also, if there are not too many possible keys to store -- that is, if each key can be represented by a small enough number of bits -- then, instead of a hash table, one may use the key directly as the index into an array of values. Note that there are no collisions in this case.

The entries stored in a hash table can be enumerated efficiently (at constant cost per entry), but only in some pseudo-random order. Therefore, there is no efficient way to locate an entry whose key is nearest to a given key. Listing all n entries in some specific order generally requires a separate sorting step, whose cost is proportional to log(n) per entry. In comparison, ordered search trees have lookup and insertion cost proportional to log(n), but allow finding the nearest key at about the same cost, and ordered enumeration of all entries at constant cost per entry.

If the keys are not stored (because the hash function is collision-free), there may be no easy way to enumerate the keys that are present in the table at any given moment.

Although the average cost per operation is constant and fairly small, the cost of a single operation may be quite high. In particular, if the hash table uses dynamic resizing, an insertion or deletion operation may occasionally take time proportional to the number of entries. This may be a serious drawback in real-time or interactive applications.

Hash tables in general exhibit poor locality of reference—that is, the data to be accessed is distributed seemingly at random in memory. Because hash tables cause access patterns that jump around, this can trigger microprocessor cache misses that cause long delays. Compact data structures such as arrays searched with linear search may be faster, if the table is relatively small and keys are compact. The optimal performance point varies from system to system.

Hash tables become quite inefficient when there are many collisions. While extremely uneven hash distributions are extremely unlikely to arise by chance, a malicious adversary with knowledge of the hash function may be able to supply information to a hash that creates worst-case behavior by causing excessive collisions, resulting in very poor performance, e.g., a denial of service attack.[25][26][27] In critical applications, a data structure with better worst-case guarantees can be used; however, universal hashing—a randomized algorithm that prevents the attacker from predicting which inputs cause worst-case behavior—may be preferable.[28] The hash function used by the hash table in the Linux routing table cache was changed with Linux version 2.4.2 as a countermeasure against such attacks.[29]

Uses

Associative arrays

Hash tables are commonly used to implement many types of in-memory tables. They are used to implement associative arrays (arrays whose indices are arbitrary strings or other complicated objects), especially in interpreted programming languages like Perl, Ruby, Python, and PHP.

When storing a new item into a multimap and a hash collision occurs, the multimap unconditionally stores both items.

When storing a new item into a typical associative array and a hash collision occurs, but the actual keys themselves are different, the associative array likewise stores both items. However, if the key of the new item exactly matches the key of an old item, the associative array typically erases the old item and overwrites it with the new item, so every item in the table has a unique key.

Database indexing

Hash tables may also be used as disk-based data structures and database indices (such as in dbm) although B-trees are more popular in these applications. In multi-node database systems, hash tables are commonly used to distribute rows amongst nodes, reducing network traffic for hash joins.

Caches

Hash tables can be used to implement caches, auxiliary data tables that are used to speed up the access to data that is primarily stored in slower media. In this application, hash collisions can be handled by discarding one of the two colliding entries—usually erasing the old item that is currently stored in the table and overwriting it with the new item, so every item in the table has a unique hash value.

Sets

Besides recovering the entry that has a given key, many hash table implementations can also tell whether such an entry exists or not.

Those structures can therefore be used to implement a set data structure, which merely records whether a given key belongs to a specified set of keys. In this case, the structure can be simplified by eliminating all parts that have to do with the entry values. Hashing can be used to implement both static and dynamic sets.

Object representation

Several dynamic languages, such as Perl, Python, JavaScript, Lua, and Ruby, use hash tables to implement objects. In this representation, the keys are the names of the members and methods of the object, and the values are pointers to the corresponding member or method.

Unique data representation

Hash tables can be used by some programs to avoid creating multiple character strings with the same contents. For that purpose, all strings in use by the program are stored in a single string pool implemented as a hash table, which is checked whenever a new string has to be created. This technique was introduced in Lisp interpreters under the name hash consing, and can be used with many other kinds of data (expression trees in a symbolic algebra system, records in a database, files in a file system, binary decision diagrams, etc.).

Transposition table

Implementations

In programming languages

Many programming languages provide hash table functionality, either as built-in associative arrays or as standard library modules. In C++11, for example, the unordered_map class provides hash tables for keys and values of arbitrary type.

The Java programming language (including the variant which is used on Android) includes the HashSet, HashMap, LinkedHashSet, and LinkedHashMap generic collections.[30]

In PHP 5, the Zend 2 engine uses one of the hash functions from Daniel J. Bernstein to generate the hash values used in managing the mappings of data pointers stored in a hash table. In the PHP source code, it is labelled as DJBX33A (Daniel J. Bernstein, Times 33 with Addition).

Python's built-in hash table implementation, in the form of the dict type, as well as Perl's hash type (%) are used internally to implement namespaces and therefore need to pay more attention to security, i.e., collision attacks. Python sets also use hashes internally, for fast lookup (though they store only keys, not values).[31]

In the .NET Framework, support for hash tables is provided via the non-generic Hashtable and generic Dictionary classes, which store key-value pairs, and the generic HashSet class, which stores only values.

In Rust's standard library, the generic HashMap and HashSet structs use linear probing with Robin Hood bucket stealing.

Independent packages

- SparseHash (formerly Google SparseHash) An extremely memory-efficient hash_map implementation, with only 2 bits/entry of overhead. The SparseHash library has several C++ hash map implementations with different performance characteristics, including one that optimizes for memory use and another that optimizes for speed.

- SunriseDD An open source C library for hash table storage of arbitrary data objects with lock-free lookups, built-in reference counting and guaranteed order iteration. The library can participate in external reference counting systems or use its own built-in reference counting. It comes with a variety of hash functions and allows the use of runtime supplied hash functions via callback mechanism. Source code is well documented.

- uthash This is an easy-to-use hash table for C structures.

History

The idea of hashing arose independently in different places. In January 1953, H. P. Luhn wrote an internal IBM memorandum that used hashing with chaining.[32] Gene Amdahl, Elaine M. McGraw, Nathaniel Rochester, and Arthur Samuel implemented a program using hashing at about the same time. Open addressing with linear probing (relatively prime stepping) is credited to Amdahl, but Ershov (in Russia) had the same idea.[32]

See also

- Rabin–Karp string search algorithm

- Stable hashing

- Consistent hashing

- Extendible hashing

- Lazy deletion

- Pearson hashing

- PhotoDNA

- Search data structure

Related data structures

There are several data structures that use hash functions but cannot be considered special cases of hash tables:

- Bloom filter, memory efficient data-structure designed for constant-time approximate lookups; uses hash function(s) and can be seen as an approximate hash table.

- Distributed hash table (DHT), a resilient dynamic table spread over several nodes of a network.

- Hash array mapped trie, a trie structure, similar to the array mapped trie, but where each key is hashed first.

References

- ↑ Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2009). Introduction to Algorithms (3rd ed.). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 253–280. ISBN 978-0-262-03384-8.

- ↑ Charles E. Leiserson, Amortized Algorithms, Table Doubling, Potential Method Lecture 13, course MIT 6.046J/18.410J Introduction to Algorithms—Fall 2005

- 1 2 3 Knuth, Donald (1998). 'The Art of Computer Programming'. 3: Sorting and Searching (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 513–558. ISBN 0-201-89685-0.

- 1 2 Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001). "Chapter 11: Hash Tables". Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. pp. 221–252. ISBN 978-0-262-53196-2.

- ↑ Pearson, Karl (1900). "On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling". Philosophical Magazine, Series 5. 50 (302). pp. 157–175. doi:10.1080/14786440009463897.

- ↑ Plackett, Robin (1983). "Karl Pearson and the Chi-Squared Test". International Statistical Review (International Statistical Institute (ISI)). 51 (1). pp. 59–72. doi:10.2307/1402731.

- 1 2 Wang, Thomas (March 1997). "Prime Double Hash Table". Archived from the original on 1999-09-03. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

- ↑ Probst, Mark (2010-04-30). "Linear vs Binary Search". Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- ↑ "How does a HashMap work in JAVA". coding-geek.com.

- ↑ Askitis, Nikolas; Zobel, Justin (October 2005). Cache-conscious Collision Resolution in String Hash Tables. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference, String Processing and Information Retrieval (SPIRE 2005). 3772/2005. pp. 91–102. doi:10.1007/11575832_11. ISBN 978-3-540-29740-6.

- ↑ Askitis, Nikolas; Sinha, Ranjan (2010). "Engineering scalable, cache and space efficient tries for strings". The VLDB Journal. 17 (5): 633–660. doi:10.1007/s00778-010-0183-9. ISSN 1066-8888.

- ↑ Askitis, Nikolas (2009). Fast and Compact Hash Tables for Integer Keys (PDF). Proceedings of the 32nd Australasian Computer Science Conference (ACSC 2009). 91. pp. 113–122. ISBN 978-1-920682-72-9.

- ↑ Erik Demaine, Jeff Lind. 6.897: Advanced Data Structures. MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Spring 2003. http://courses.csail.mit.edu/6.897/spring03/scribe_notes/L2/lecture2.pdf

- ↑ Willard, Dan E. (2000). "Examining computational geometry, van Emde Boas trees, and hashing from the perspective of the fusion tree". SIAM Journal on Computing. 29 (3): 1030–1049. doi:10.1137/S0097539797322425. MR 1740562..

- 1 2 Tenenbaum, Aaron M.; Langsam, Yedidyah; Augenstein, Moshe J. (1990). Data Structures Using C. Prentice Hall. pp. 456–461, p. 472. ISBN 0-13-199746-7.

- ↑ Herlihy, Maurice; Shavit, Nir; Tzafrir, Moran (2008). "Hopscotch Hashing". DISC '08: Proceedings of the 22nd international symposium on Distributed Computing. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. pp. 350–364.

- ↑ Celis, Pedro (1986). Robin Hood hashing (PDF) (Technical report). Computer Science Department, University of Waterloo. CS-86-14.

- ↑ Goossaert, Emmanuel (2013). "Robin Hood hashing".

- ↑ Amble, Ole; Knuth, Don (1974). "Ordered hash tables". Computer Journal. 17 (2): 135. doi:10.1093/comjnl/17.2.135.

- ↑ Viola, Alfredo (October 2005). "Exact distribution of individual displacements in linear probing hashing". Transactions on Algorithms (TALG). ACM. 1 (2,): 214–242. doi:10.1145/1103963.1103965.

- ↑ Celis, Pedro (March 1988). External Robin Hood Hashing (Technical report). Computer Science Department, Indiana University. TR246.

- ↑ http://www.eecs.harvard.edu/~michaelm/postscripts/handbook2001.pdf

- ↑ Litwin, Witold (1980). "Linear hashing: A new tool for file and table addressing". Proc. 6th Conference on Very Large Databases. pp. 212–223.

- ↑ Doug Dunham. CS 4521 Lecture Notes. University of Minnesota Duluth. Theorems 11.2, 11.6. Last modified April 21, 2009.

- ↑ Alexander Klink and Julian Wälde's Efficient Denial of Service Attacks on Web Application Platforms, December 28, 2011, 28th Chaos Communication Congress. Berlin, Germany.

- ↑ Mike Lennon "Hash Table Vulnerability Enables Wide-Scale DDoS Attacks". 2011.

- ↑ "Hardening Perl's Hash Function". November 6, 2013.

- ↑ Crosby and Wallach. Denial of Service via Algorithmic Complexity Attacks. quote: "modern universal hashing techniques can yield performance comparable to commonplace hash functions while being provably secure against these attacks." "Universal hash functions ... are ... a solution suitable for adversarial environments. ... in production systems."

- ↑ Bar-Yosef, Noa; Wool, Avishai (2007). Remote algorithmic complexity attacks against randomized hash tables Proc. International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT) (PDF). p. 124.

- ↑ https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/collections/implementations/index.html

- ↑ https://stackoverflow.com/questions/513882/python-list-vs-dict-for-look-up-table

- 1 2 Mehta, Dinesh P.; Sahni, Sartaj. Handbook of Datastructures and Applications. p. 9-15. ISBN 1-58488-435-5.

Further reading

- Tamassia, Roberto; Goodrich, Michael T. (2006). "Chapter Nine: Maps and Dictionaries". Data structures and algorithms in Java : [updated for Java 5.0] (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 369–418. ISBN 0-471-73884-0.

- McKenzie, B. J.; Harries, R.; Bell, T. (Feb 1990). "Selecting a hashing algorithm". Software Practice & Experience. 20 (2): 209–224. doi:10.1002/spe.4380200207.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hash tables. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Data Structures/Hash Tables |

- A Hash Function for Hash Table Lookup by Bob Jenkins.

- Hash Tables by SparkNotes—explanation using C

- Hash functions by Paul Hsieh

- Design of Compact and Efficient Hash Tables for Java

- Libhashish hash library

- NIST entry on hash tables

- Open addressing hash table removal algorithm from ICI programming language, ici_set_unassign in set.c (and other occurrences, with permission).

- A basic explanation of how the hash table works by Reliable Software

- Lecture on Hash Tables

- Hash-tables in C—two simple and clear examples of hash tables implementation in C with linear probing and chaining, by Daniel Graziotin

- Open Data Structures – Chapter 5 – Hash Tables

- MIT's Introduction to Algorithms: Hashing 1 MIT OCW lecture Video

- MIT's Introduction to Algorithms: Hashing 2 MIT OCW lecture Video

- How to sort a HashMap (Java) and keep the duplicate entries

- How python dictionary works