William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount Brentford

| The Right Honourable The Viscount Brentford Bt PC PC (NI) DL | |

|---|---|

William Joynson-Hicks in 1923 | |

| Home Secretary | |

|

In office 7 November 1924 – 5 June 1929 | |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Arthur Henderson |

| Succeeded by | J. R. Clynes |

| Minister of Health | |

|

In office 27 August 1923 – 22 January 1924 | |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Neville Chamberlain |

| Succeeded by | John Wheatley |

| Financial Secretary to the Treasury (Office in Cabinet) | |

|

In office 25 May 1923 – 27 August 1923 | |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Archibald Boyd-Carpenter |

| Succeeded by | (from 5 October 1923) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

23 June 1865 Plaistow Hall, Kent |

| Died |

8 June 1932 (aged 66) London |

| Nationality | English |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse(s) |

Grace Lynn Joynson (d. 1952) |

William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount Brentford PC, PC (NI), DL (23 June 1865 – 8 June 1932), known as Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Bt, from 1919 to 1929 and popularly known as Jix, was an English solicitor and Conservative Party politician, best known as a long-serving and controversial Home Secretary from 1924 to 1929, during which he gained a reputation for strict authoritarianism.

Background and early life

Born William Hicks, he was the eldest of four sons and two daughters of Henry Hicks, of Plaistow Hall, Kent, and his wife Harriett, daughter of William Watts. Hicks was a prosperous merchant and senior evangelical Anglican layman[1] who demanded the very best from his children.[2] William Hicks was educated at Merchant Taylors' School, London. After leaving school, he was articled to a solicitor between 1881 and 1887, before setting up his own practice in 1888. Initially he struggled to attract clients, but Henry Hicks became associated with the London General Omnibus Company and this connection gained his son much legal work. It also made him an early authority on transport law, particularly motoring law. He was a founder member of The Automobile Association and served as its chairman for fifteen years.[3] In 1894 while on holiday, he met Grace Joynson, the daughter of a Lancashire silk manufacturer. They were married the following year, Hicks subsequently adding his wife's maiden name to his own.[4]

Entering Parliament

He joined the Conservative Party (at that time part of the Unionist coalition, which name it retained until 1925) and unsuccessfully contested seats in Manchester in the general elections of 1900 and 1906, but was elected in a by-election in 1908. Winston Churchill was obliged to submit to re-election in Manchester North West after his appointment as President of the Board of Trade, as the Ministers of the Crown Act 1908 required newly appointed Cabinet ministers to re-contest their seats. As Churchill had crossed the floor from the Conservatives to the Liberals in 1904, the Conservatives were disinclined to allow him an uncontested return. Joynson-Hicks was adopted against him and in a high-profile campaign defeated Churchill. This provoked a strong reaction across the country with The Daily Telegraph running the front page headline "Winston Churchill is OUT! OUT! OUT!" This election was notable for both the attacks of the Suffragette movement on Churchill, over his refusal to support legislation that would give women the vote, and Jewish hostility to Joynson-Hicks over his support for the controversial Aliens Act.[5]

Joynson-Hicks gained personal notoriety in the immediate aftermath of this election for an address to his Jewish hosts at a dinner given by the Maccabean Society, during which he said "he had beaten them all thoroughly and soundly and was no longer their servant."[6] Subsequent allegations that he was personally anti-Semitic have been frequently and thoroughly discussed. It has formed an important strand of the authoritarian streak that many, including recent scholars David Cesarani and Geoffrey Alderman, have detected in his speeches and behaviour. It also led to the nickname "Mussolini Minor" being coined for him, something that led Cesarani to caution "Although he may have been nicknamed "Mussolini Minor", Jix was no fascist."[7] Other work has disputed the notion that Joynson-Hicks was an anti-Semite, most notably a major article by W. D. Rubinstein which asserted Joynson-Hicks had allowed more Jews to be naturalized than any other Home Secretary.[8] Whether or not it was justified, the notion that Joynson-Hicks was an anti-Semite has played a large part in his portrayal as a narrow-minded and intolerant man, most obviously in the work of Ronald Blythe.[9]

Joynson-Hicks lost the seat in the January 1910 general election but was elected for the seat of Brentford in 1911, switching to Twickenham in 1918, a seat that he held until 1929. During the First World War he formed a Pals battalion within the Middlesex Regiment, the "Football Battalion," and continued to speak on matters pertaining to transport, especially Air Defence. However, he was not offered a government post. For his war work, he was created a Baronet, of Holmbury in the County of Surrey, in 1919.[10]

The Lloyd George Coalition

In 1919 he went on an extended visit to India, which changed his political fortunes. At the time, there was considerable unrest in India and a rapid growth in the Home Rule movement, something Joynson-Hicks opposed due to the great economic importance of the Indian Empire to Britain. He at one time had commented "I know it is frequently said at missionary meetings that we conquered India to raise the level of the Indians. That is cant. We hold it as the finest outlet for British goods in general, and for Lancashire cotton goods in particular."[11]

He emerged as a strong supporter of General Reginald Dyer over the Amritsar Massacre, and nearly forced the resignation of the Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, over the motion of censure the government put down concerning Dyer's actions.[12] This episode established his reputation as one of the "die-hards" on the right-wing of the party, and he emerged as a strong critic of the party's participation in a coalition government with the Liberal David Lloyd George.

As part of this campaign, he led an abortive attempt to block Austen Chamberlain's nomination as leader of the Unionist party on Andrew Bonar Law's retirement, putting forward Lord Birkenhead instead with the express aim of "splitting the coalition".[13]

Entering government

When the coalition fell in October 1922 and most of its leading Unionist members refused to serve in government, Joynson-Hicks was appointed Secretary for Overseas Trade. In the fifteen-month Conservative administration of first Andrew Bonar Law and then Stanley Baldwin, Joynson-Hicks was rapidly promoted, often filling positions left vacant by the promotion of Neville Chamberlain. In 1923, he became Paymaster-General then Postmaster General. When Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister, he initially also retained his previous position of Chancellor of the Exchequer whilst searching for a permanent successor. To relieve the burden of this position, he promoted Joynson-Hicks to Financial Secretary to the Treasury and included him in the Cabinet.

In that role, Joynson-Hicks was responsible for making the Hansard statement, on 19 July 1923, that the Inland Revenue would not prosecute a defaulting taxpayer who made a full confession and paid the outstanding tax, interest and penalties. Joynson-Hicks had hopes of eventually becoming Chancellor himself, but instead Neville Chamberlain was appointed to the post in August 1923. Once more, Joynson-Hicks filled the gap left by Chamberlain's promotion, serving as Minister of Health. He became a Privy Counsellor in 1923.[14] Following the hung parliament, amounting to a Unionist defeat in the general election of 1923, Joynson-Hicks became a key figure in various intra-party attempts to oust Baldwin.

At one time, the possibility of his becoming leader himself was discussed, but it seems to have been quickly discarded. He was involved in a plot to persuade Arthur Balfour that should the King seek his advice on who to appoint Prime Minister, Balfour would advise him to appoint Austen Chamberlain or Lord Derby Prime Minister instead of Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald. The plot failed when Balfour refused to countenance such a move and the Liberals publicly announced they would support MacDonald, causing the government to fall in January 1924.[15]

Home Secretary

The Conservatives returned to power in November 1924 and Joynson-Hicks was appointed to his most famous role, that of Home Secretary. In this role he was portrayed as a reactionary for his attempts to crack down on night clubs and other aspects of the "Roaring Twenties". He was also heavily implicated in the banning of Radclyffe Hall's novel on a lesbian theme, The Well of Loneliness in which he took a personal interest.[16] During the General Strike of 1926, he was a leading organizer of the systems that maintained supplies and law and order, although there is some evidence that left to himself he would have pursued a more hawkish policy – most notably, his repeated appeals for more volunteer constables and his attempt to close down the Daily Herald.[17]

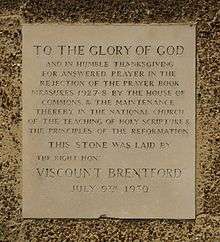

In 1927 Joynson-Hicks turned his fire on the proposed new version of the Book of Common Prayer. The law required Parliament to approve such revisions, normally regarded as a formality, but when the Prayer Book came before the House of Commons Joynson-Hicks argued strongly against its adoption as he felt it strayed far from the Protestant principles of the Church of England. The debate on the Prayer Book is regarded as one of the most eloquent ever seen in the Commons, and resulted in the rejection of the revised Prayer Book. A further revised version was submitted in 1928 but rejected again. However, the National Assembly of the Church of England then declared an emergency, and this was argued as a pretext for the use of the 1928 Prayer Book in many churches for decades afterwards.[18]

Joynson-Hicks was also responsible for piloting the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 through Parliament, which allowed women to vote on the same terms as men. He made a strong speech in support of the Bill, and was blamed for the Conservatives' unexpected electoral defeat the following year, which the right of the party attributed to newly enfranchised young women (referred to derogatorily as "flappers") voting for the opposition Labour party. This led to the creation by Winston Churchill of the oft-repeated legend that Joynson-Hicks had committed the party to giving votes to young women with a parliamentary pledge to Lady Astor in 1925 – a claim that has entered popular mythology but has no basis in fact.[19]

Throughout his tenure at the Home Office, Joynson-Hicks was noted for his reform of the penal system – in particular, Borstal reform and the introduction of a legal requirement for all courts to have a probation officer. He made a point of visiting all the prisons in the country, and was often dismayed by what he found there.[20] He made a concerted effort to improve the conditions of the prisons under his jurisdiction, and earned a compliment from persistent offender and night-club owner Kate Meyrick, who noted in her memoirs that prisons had improved considerably thanks to his efforts.[21]

The Conservatives lost power in 1929, and Joynson-Hicks was raised to the peerage as the Viscount Brentford, of Newick in the County of Sussex in the Dissolution Honours.[22] He remained a leading figure in the Conservative Party, but due to his declining health he was not invited to join the National Government in either August or November 1931.

Family

Lord Brentford married Grace Lynn, only daughter of Richard Hampson Joynson, JP, of Bowdon Cheshire, on 12 June 1895 in St. Margaret's Church, Westminster. They had two sons and one daughter. He died in June 1932, aged 66, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Richard. His youngest son, the Hon. Lancelot (who succeeded in the viscountcy in 1958), was also a Conservative politician. The Viscountess Brentford died in January 1952.

Subsequent reputation

Although Joynson-Hicks was Home Secretary, a notoriously difficult office to hold, for some four and a half years, he is frequently overlooked by both historians and politicians. His length of tenure was exceeded in the twentieth century only by Chuter Ede, R. A. Butler and Herbert Morrison,[23] yet he was not included in a list of long-serving Home Secretaries presented to Jack Straw in 2001 on his departure from the Home Office.[24] He is also virtually the only major politician of the 1920s not to have been accorded a recent biography.

For many years detailed discussion of Joynson-Hicks' life and career was hampered by the inaccessibility of his papers, which were kept by the Brentford family. This meant the discourse on his life was shaped by the official biography of 1933 by H. A. Taylor, and by material published by his contemporaries – much of it published by people who hated him. As a result, public discourse has been shaped by material that portrayed him in an unflattering light. Ronald Blythe's biographical chapter in The Age of Illusion is perhaps the apogee of this tendency. Huw Clayton, a former pupil of W. D. Rubinstein, commented that "to refer to The Age of Illusion as Irvingesque would be to overstate the case, yet I managed to get even one of Blythe's admirers to admit that the chapter on Joynson-Hicks (where he somehow worked the word "paederast" into the debate) was an unfair caricature of the man".[25]

In the 1990s the current Viscount lent his grandfather's papers to an MPhil student at the University of Westminster, Jonathon Hopkins,[26] who prepared a catalogue of them and wrote a short biography of Joynson-Hicks as part of his thesis.[27] In 2007, a number of these papers were deposited with the East Sussex Record Office in Lewes (which transferred to The Keep in Brighton in 2013) where they are available to the public.[28] Following this Huw Clayton, whose PhD thesis concerned Joynson-Hicks' moral policies at the Home Office, has announced that he plans to write a new biography of Joynson-Hicks with the aid of these sources.[27] An article on Joynson-Hicks, written by Clayton, has since appeared in the Journal of Historical Biography – it is unclear whether this is what he meant by a new biography, or whether it is an interim measure prior to a full book.[29]

References

- ↑ Paul Zahl (1997). The Protestant Face of Anglicanism. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8028-4597-9.

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 14–15

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Blythe, p. 23

- ↑ Paul Addison, Churchill on the Home Front 1900–1955 (2nd ed., London 1993) p. 64

- ↑ W. D. Rubinstein (1993). "Recent Anglo-Jewish Historiography and the Myth of Jix's Anti-Semitism, Part Two". Australian Journal of Jewish Studies. 7 (2): 24–45, 35.

- ↑ David Cesarani, "Joynson-Hicks and the Radical Right in England after the First World War" in Tony Kushner and Kenneth Lunn (eds.) Traditions of Intolerance: Historical Perspectives on Fascism and Race Discourse in Britain (Manchester 1989) pp. 118–139, p. 134

- ↑ Rubinstein "Recent Anglo-Jewish Historiography", Australian Journal of Jewish Studies 7 (1993) part one in 7:1 pp. 41–70, part two in 7:2 pp. 24–45

- ↑ Blythe, p. 27

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 31587. p. 12418. 7 October 1919. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ↑ Quoted in Blythe, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Cesarani p. 123 (he wrongly credits this campaign with toppling Montagu, who in fact stayed in office until the Lloyd George coalition fell in 1922)

- ↑ Max Aitken, Decline and Fall of Lloyd George: and great was the fall thereof (London 1963) p. 21

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 32809. p. 2303. 27 March 1923. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ↑ Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Labour 1920–1924: The Beginning of Modern British Politics (Cambridge 1971) pp. 332–333, 384

- ↑ Diana Souhami, The Trials of Radclyffe Hall (London 1999) pp. 180–181: a more recent but unfortunately not widely available account of these actions may be found in Huw Clayton, "A Frisky, Tiresome Colt?" Sir William Joynson-Hicks, the Home Office and the "Roaring Twenties" in London, 1924–1929" Aberystwyth University PhD thesis (2009)

- ↑ Anne Perkins, A Very British Strike: 3–12 May 1926 (London 2006) pp. 160, 180, 138–9

- ↑ Ross McKibbin, Classes and Cultures: England 1918–1951 (Oxford 1998) pp. 277–278

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 282–285

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 186–189

- ↑ Kate Meyrick, Secrets of the 43 (2nd ed., Dublin 1994) p. 80

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 33515. p. 4539. 9 July 1926. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ↑ List available in David Butler and Gareth Butler, Twentieth Century British Political Facts 1900–2000 (revised eighth edition Basingstoke 2005) p. 56

- ↑ Matthew D'Ancona, "Mr Blair is now, at best, a politician in remission," Sunday Telegraph (Opinion Section) 26 March 2006: article on Telegraph website

- ↑ Blythe, p. 35

- ↑ Cameron Hazlehurst et al. (eds) A Guide to the Papers of British Cabinet Ministers 1900–1964 (London 1997) p. 185

- 1 2 "William Joynson-Hicks « Doctor Huw". Doctorhuw.wordpress.com. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ National Register of Archives: Accessions to Repositories 2007: East Sussex Record Office. nationalarchives.gov.uk

- ↑ Huw Clayton (2010). "The Life and Career of William Joynson-Hicks 1865–1932: A Reassessment" (PDF). The Journal of Historical Biography. 8: 1–32.

Bibliography

- Blythe, Ronald (1963). "Ch. 2 "The Salutary Tale of Jix"". The Age of Illusion: England in the Twenties and Thirties 1919–1940. London.

- Taylor, H. A. (1933). Jix, Viscount Brentford: being the authoritative and official biography of the Rt. Hon. William Joynson-Hicks, First Viscount Brentford of Newick. London.

Further reading

- Alderman, Geoffrey, "Recent Anglo-Jewish Historiography and the Myth of Jix's Anti-Semitism: A Response" Australian Journal of Jewish Studies 8:1 (1994)

- – "The Anti-Jewish Career of Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Cabinet Minister,' Journal of Contemporary History 24 (1989) pp. 461–482

- Perkins, Anne, A Very British Strike: 3–12 May 1926 London 2006

- - "Professor Alderman and Jix: A Response" Australian Journal of Jewish Studies 8:2 (1994) pp. 192–201

- Thompson, F. M. L. (January 2008). "Hicks, William Joynson- , first Viscount Brentford (1865–1932)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

Other sources on Joynson-Hicks:

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by William Joynson-Hicks

- Hopkins, Jonathon M., "Paradoxes Personified: Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Viscount Brentford and the conflict between change and stability in British Society in the 1920s" University of Westminster MPhil thesis (1996): copy available at the East Sussex Record Office.

- National Register of Archives: Accessions to Repositories 2007: East Sussex Record Office: "Search other Archives | Accessions to Repositories | Major Accessions to East Sussex Record Office, 2007". The National Archives. Retrieved 16 April 2010. link to ESRO website: "East Sussex Record Office". Eastsussex.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount Brentford. |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Viscount Brentford

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Winston Churchill |

Member of Parliament for Manchester North West 1908–January 1910 |

Succeeded by George Kemp |

| Preceded by Lord Alwyne Compton |

Member of Parliament for Brentford 1911–1918 |

Constituency abolished |

| New constituency | Member of Parliament for Twickenham 1918–1929 |

Succeeded by John Ferguson |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Archibald Boyd-Carpenter |

Financial Secretary to the Treasury 1923 |

Succeeded by Walter Guinness |

| Preceded by Neville Chamberlain |

Paymaster General 1923 |

Succeeded by Archibald Boyd-Carpenter |

| Postmaster General 1923 |

Succeeded by Sir Laming Worthington-Evans, Bt | |

| Minister of Health 1923–1924 |

Succeeded by John Wheatley | |

| Preceded by Arthur Henderson |

Home Secretary 1924–1929 |

Succeeded by J. R. Clynes |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Viscount Brentford 1929–1932 |

Succeeded by Richard Cecil Joynson-Hicks |

| Baronetage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Baronet (of Holmbury) 1919–1932 |

Succeeded by Richard Cecil Joynson-Hicks |

.svg.png)