Histopathology

Histopathology (compound of three Greek words: ἱστός histos "tissue", πάθος pathos "suffering", and -λογία -logia "study of") refers to the microscopic examination of tissue in order to study the manifestations of disease. Specifically, in clinical medicine, histopathology refers to the examination of a biopsy or surgical specimen by a pathologist, after the specimen has been processed and histological sections have been placed onto glass slides. In contrast, cytopathology examines free cells or tissue fragments.

Collection of tissues

Histopathological examination of tissues starts with surgery, biopsy, or autopsy. The tissue is removed from the body or plant, and then placed in a fixative which stabilizes the tissues to prevent decay. The most common fixative is formalin (10% formaldehyde in water).

Preparation for histology

The tissue is then prepared for viewing under a microscope using either chemical fixation or frozen section.

If a large sample is provided e.g. from a surgical procedure then a pathologist looks at the tissue sample and selects the part most likely to yield a useful sample - this part is removed for examination in a process commonly known as cut up. This is then placed into a plastic cassette for most of the rest of the process [1]

Chemical Fixation

Water is removed from the sample in successive stages by the use of increasing concentrations of alcohol.[1] Xylene is used in the last dehydration phase instead of alcohol - this is because the wax used in the next stage is soluble in xylene where it is not in alcohol allowing wax to permeate the specimen.[1] Finally, molten wax is introduced into the specimen.[1] Further wax is added to the cassette surrounding the sample, producing a wax block with the sampled embedded within. This process is generally automated and done overnight. It is needed to provide a sample sturdy enough for obtaining a thin section for the slide.

Once the wax block is finished, sections will be cut from it. This is usually done by hand and is a skilled job with the lab personnel making choices about which parts of the specimen to place on slides.A number of slides will usually be prepared from different levels throughout the block. After this the thin section is stained and placed on a slide with a protective cover slip. For common stains and automatic process is normally used but rarely used stains are often done by hand.[1]

Frozen section processing

The second method of histology processing is called frozen section processing. This is a highly technical scientific method performed by a trained histoscientist (a Medical Laboratory scientist specialist in Histopathology. 5–6 years degree training) In this method, the tissue is frozen and sliced thinly using a microtome mounted in a below-freezing refrigeration device called the cryostat. The thin frozen sections are mounted on a glass slide, fixed immediately & briefly in liquid fixative, and stained using the similar staining techniques as traditional wax embedded sections. The advantages of this method is rapid processing time, less equipment requirement, and less need for ventilation in the laboratory. The disadvantage is the poor quality of the final slide. It is used in intra-operative pathology for determinations that might help in choosing the next step in surgery during that surgical session (for example, to preliminarily determine clearness of the resection margin of a tumor during surgery).

Staining of processed histology slides

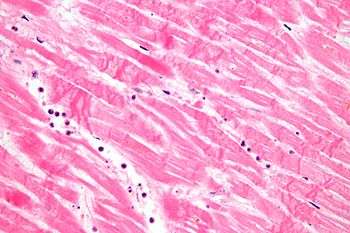

This can be done to slides processed by the chemical fixation or frozen section slides. To see the tissue under a microscope, the sections are stained with one or more pigments. The aim of staining is to reveal cellular components; counterstains are used to provide contrast.

The most commonly used stain in histopathology is a combination of hematoxylin and eosin (often abbreviated H&E). Hematoxylin is used to stain nuclei blue, while eosin stains cytoplasm and the extracellular connective tissue matrix pink. There are hundreds of various other techniques which have been used to selectively stain cells. Other compounds used to color tissue sections include safranin, Oil Red O, congo red, silver salts and artificial dyes. Histochemistry refers to the science of using chemical reactions between laboratory chemicals and components within tissue. A commonly performed histochemical technique is the Perls' Prussian blue reaction, used to demonstrate iron deposits in diseases like Hemochromatosis.[2]

Recently, antibodies have been used to stain particular proteins, lipids and carbohydrates. Called immunohistochemistry, this technique has greatly increased the ability to specifically identify categories of cells under a microscope. Other advanced techniques include in situ hybridization to identify specific DNA or RNA molecules. These antibody staining methods often require the use of frozen section histology. These procedures above are also carried out in the laboratory under scrutiny and precision by a trained specialist Medical laboratory scientist (Histoscientist) Digital cameras are increasingly used to capture histopathological images.

Interpretation

The histological slides are examined under a microscope by a pathologist, a medically qualified specialist who has completed a recognised training program (5 - 5.5 years in the United Kingdom). This medical diagnosis is formulated as a pathology report describing the histological findings and the opinion of the pathologist. In the case of cancer, this represents the tissue diagnosis required for most treatment protocols. In the removal of cancer, the pathologist will indicate whether the surgical margin is cleared, or is involved (residual cancer is left behind). This is done using either the bread loafing or CCPDMA method of processing.

In myocardial infarction

After a myocardial infarction (heart attack), no histopathology is seen the first ~30 minutes. The only possible sign the first 4 hours is waviness of fibres at border. Later, however, a coagulation necrosis is initiated, with edema and hemorrhage. After 12 hours, there can be seen karyopyknosis and hypereosinophilia of myocytes with contraction band necrosis in margins, as well as beginning of neutrophil infiltration. At 1 – 3 days there is continued coagulation necrosis with loss of nuclei and striations and an increased infiltration of neutrophils to interstitium. Until the end of the first week after infarction there is beginning of disintegration of dead muscle fibres, necrosis of neutrophils and beginning of macrophage removal of dead cells at border, which increases the succeeding days. After a week there is also beginning of granulation tissue formation at margins, which matures during the following month, and gets increased collagen deposition and decreased cellularity until the myocardial scarring is fully mature at approximately 2 months after infarction.[3]

See also

- Anatomical pathology

- Molecular pathology

- Frozen section procedure

- Medical technologist

- Laser capture microdissection

- List of pathologists

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 http://www.mwap.co.uk/path_staining.html

- ↑ http://www.scribd.com/doc/4448747/Perl Perls' Prussian blue original formula and uses. Accessed April 2, 2009.

- ↑ Chapter 11 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.

External links

- Virtual Histology Course - University of Zurich (German, English version in preparation)

- Histopathology of the uterine cervix - digital atlas (IARC Screening Group)

- PathologyPics.com: An interactive histology database for the Practicing Anatomic Pathologist as well as Pathology Trainees.

- Histopathology Virtual Slidebox - University of Iowa