History of Dedham, Massachusetts, 1635–1792

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Dedham |

|---|

|

| Main articles |

| People |

| Places |

| Organizations |

The history of Dedham, Massachusetts, began with the first settlers' arrival in 1635. The Puritans who built the village on what the Indians called Tiot incorporated the plantation in 1636. They devised a form of government in which almost every freeman could participate and eventually chose selectmen to run the affairs of the town. They then formed a church and nearly every family had at least one member.

The early residents of town built the first American canal, the first tax supported public school, run by Ralph Wheelock, and Jonathan Fairbanks built what is today the oldest woodframe house in North America.

Dedham is one of the few towns founded during the colonial era that has preserved extensive records of its earliest years.

Early years

In 1635 there were rumors in the Massachusetts Bay Colony that a war with the local Indians was impending and a fear arose that the few, small, coastal communities that existed were in danger of attack. This, in addition to the belief that the few towns that did exist were too close together, prompted the Massachusetts General Court to establish two new inland communities. The towns of Dedham and Concord, Massachusetts were thus established to relieve the growing population pressure and to place communities between the larger, more established coastal towns and the Indians further west.[1]

Landing and first settlement

Dedham was settled in the summer of 1636 by "about thirty families excised from the broad ranks of the English middle classes"[2] traveling up the Charles River from Roxbury and Watertown traveling in rough canoes carved from felled trees.[3] These original settlers, including Edward Alleyne, John Everard, John Gay and John Ellis "paddled up the narrow, deeply flowing stream impatiently turning curve after curve around Nonantum until, emerging from the tall forest into the open, they saw in the sunset glow a golden river twisting back and forth through broad, rich meadows."[3] In search of the best land available to them they continued on but

The river took many turns, so that it was a burden the continual turning about.... West, east, and north we turned on that same meadow and progressed none, so that I, rising in the boat, saw the river flowing just across a bit of grass, in a place where I knew we had passed through nigh an hour before. "Moore," said Miles then to me, "the river is like its Master, our good King Charles, of sainted memory, it promises overmuch, but gets you nowhere."[3]

They first landed where the river makes its 'great bend,'[3] near what is today Ames Street, and close by the Dedham Community House and the Allin Congregational Church in Dedham Square. The site is known as "the Keye," and in 1927 a stone bench and memorial plaque were installed on the site.[4]

The Algonquians living in the area called the place Tiot.[5] Tiot, which means "land surrounded by water," was later used to describe the village of South Dedham, today the separate town of Norwood.[6] In "its first years, the town was more than a place to live; it was a spiritual community."[7]

Many of the other yeomen settling the new Dedham in the Massachusetts Bay Colony came from Suffolk, in eastern England. This group included elders Nathan Aldis, George Barber, Henry Brock, Eleazor Lusher, Samuel Morse, Robert Ware, John Thurston, Francis and Henry Chickering and Anthony, Corneileus and Joshua Fisher.[8]

Of towns founded during the colonial era, Dedham is one of the few towns "that has preserved extensive records of its earliest years."[7] They have been described as "very full and perfect."[5]

Forming a government

The settlers petitioned the General Court to incorporate the plantation into a town, and to free the town from all "Countrey Charges" for four years and from all military exercises unless "extraordinary occasion require it."[9] They also asked to "distinguish our town by the name of Contentment"[9] but when the "prosaic minds" in the Court granted the petition on September 7, 1636 they decreed that the "Towne shall beare the name of Dedham."[10][11] The town was named for Dedham, Essex, where some of the original inhabitants, including John Dwight, John Page and John Rogers had been born.[3] "Contentment" eventually became the motto of the town.

Covenant

The first public meeting of the plantation they called Contentment was held on August 18, 1636[12] and the town covenant was signed; eventually 125 men would ascribe their names to the document. As the Covenant stipulated that "for the better manifestation of our true resolution herein, every man so received into the town is to subscribe hereunto his name, thereby obliging both himself and his successors after him forever."[13] They swore that they would "in the fear and reverence of our Almighty God, mutually and severally promise amongst ourselves and each to profess and practice one truth according to that most perfect rule, the foundation whereof is ever lasting love."[13]

They also agreed that "we shall by all means labor to keep off from us all such as are contrary minded, and receive only such unto us as may be probably of one heart with us, [and such] as that we either know or may well and truly be informed to walk in a peacable conversation with all meekness of spirit, [this] for the edification of each other in the knowledge and faith of the Lord Jesus..."[14] Before a man could join the community he underwent a public inquisition to determine his suitability.[14] Every signer of the Covenant was required to tell all he knew of the other men and if a lie was uncovered the man who spoke it would be instantly excluded from town.[12]

The covenant also stipulated that if differences were to arise between townsmen that they would submit the issue to between one and four other members of the town for resolution,[13] "eschew[ing] all appeals to law and submit[ting] all disputes between them to arbitration.[15] This arbitration system was so successful that there were no need for courts.[nb 1] The commitment in the Covenant to allow only like-minded individuals to live within the town explains why "church records show no instances of dissension, Quaker or Baptist expulsions, or witchcraft persecutions."[1] They also agreed to pay their fair share for the common good.[13]

In 1857, however, the growth of the Town was limited to descendants of the those living there at the time.[16] Newcomers could settle there, so long as they were like-minded, but they would have to buy their way into the community.[16] Land was no longer freely available for those who wished to join.[16]

Town Meeting

The Town Meeting "was the original and protean vessel of local authority. The founders of Dedham had met to discuss the policies of their new community even before the General Court had defined the nature of town government."[17] "In theory, the power of the town meeting knew no limit."[18] The early meetings were informal, with all men in Town likely participating. A colony law required all voters to be Church members until 1647, though it may not have been enforced. Even if it were 70% of the men in town would have been eligible to participate.[18]

Attendance at Meetings was considered vital for the life of the community. The town meeting

created principals to regulate taxation and land distribution; it bought land for town use and forbade the use of it forever to those who could not pay their share within a month; it decided the number of pines each family could cut from the swamp and which families could cover their house with clapboard. The men who went to that town meeting hammered out the abstract principles under which they would live and regulated the most minute details of their lives. The decisions they made then affected the lives of their children and grandchildren.[19]

It was often the case that even after "meetings [had] been agreed upon and times appointed accordingly" many townsmen would still arrive late to the meeting and those who arrived promptly "wasted much time to their great damage."[20] To discourage tardiness the town set fines in 1636 of one shilling for arriving more than half an hour after the "beating of the drum" and two sixpence shilling if a member was completely absent. In 1637 those fines increased to twelve pence for being late and three shillings and four pence for not arriving at all.[20]

The more wealthy a voter was, the more likely he would attend the meeting. However, "even though no more than 58 men were eligible to come to the Dedham town meeting and to make the decisions for the town, even though the decisions to which they addressed themselves were vital to their existence, even though every inhabitant was required to live within one mile (1.6 km) of the meeting place, even though each absence from the meeting brought a fine, and even though the town crier personally visited the house of every latecomer half an hour after the meeting had begun, only 74 percent of those eligible actually showed up at the typical town meeting between 1636 and 1644."[19]

While the Meeting soon appointed selectmen to handle most of the Town's affairs, it was the meeting that created the Board and the Meeting could just as easily dissolve it. The Meeting would occasionally vote on the actions of the Selectmen, and choose to either approve or disapprove of them.[18] However, "its theoretical powers were fore the most part symbolic" and "[f]ormal review of the acts and accounts of the executive was sporadic and at best perfunctory."[21][16]

The meeting operated on a basis of consensus.[16]

Selectmen

The whole town would gather regularly to conduct public affairs, but it was "found by long experience that the general meeting of so many men…has wasted much time to no small damage and business is thereby nothing furthered."[17] In response, on May 3, 1639, seven selectmen were chosen "by general consent" and given "full power to contrive, execute and perform all the business and affairs of this whole town"[17] The leaders they chose "were men of proven ability who were known to hold the same values and to be seeking the same goals as their neighbors" and they were "invested with great authority."[22] The empowering of several selectmen to administer the affairs of the town was soon seen by the whole colony to have great value, and after the General Court approved of it, nearly all towns began choosing selectmen of their own.[17]

Soon the selectmen "enjoyed almost complete control over every aspect of local administration."[23] They met roughly 10 times a year for formal sessions, and more often in informal subcommittees. They also served like a court, determining who had broken by-laws and issuing fines. Almost all townsmen would have to appear before them at one point or another during the year to ask for a swap of land, to ask to remove firewood from the common lands or for some other purpose.[23] The selectmen shared the power to appoint men to positions with the Town Meeting but they retained "a strong initiative" to act on their own. They wrote most of the laws in the town, and they levied taxes on their fellow townsmen.[24]

Selectmen were "the most powerful men in town. As men, they were few in number, old, and relatively rich and [members] of the church."[25] Throughout the 17th century the selectmen, "particularly those elected again and again for ten or twenty years, owned considerably more land than the average citizen. Between 1640 and 1740 'the selectmen were almost without exception in the most wealthy 20 percent of the town. Often, a majority of a particular board would be found in the top 10 percent."[26] Men who were not members of the church were still allowed to hold town office, however, in light of the "high rate of admissions, the townsmen may have assumed that [they] would be members soon enough."[27]

The men chosen to serve were consistently sent back to serve multiple year long terms on the Board. Between 1637 and 1639 there were 43 different men chosen as selectmen and they served on average 8 terms each. In that time period there were 10 men who served an average of 20 terms each. They made up only 5% of the population but filled 60% of the seats on the Board. An additional 15 men served an average of 10 terms each, filling 30% of the seats. These 15 usually left office only when they had an early death or they removed from town.[25] If a man served more than three terms he could usually count on returning for many more.[28]

The burdens of office could take up to a third of their time during busy seasons. They served without salary and came up through the ranks of lower offices. In return they became "men of immense prestige" and were frequently selected to serve in other high posts.[29] For 45 of the first 50 years of Dedham's existence one of the 10 selectmen who served most often also served in "the one superior [the Town] recognized, the General Court."[30]

Forming a church

While it was of the utmost importance, "founding a church was more difficult than founding a town."[31] Meetings were held late in 1637 and were open to "all the inhabitants who affected church communion... lovingly to discourse and consult together [on] such questions as might further tend to establish a peaceable and comfortable civil society ad prepare for spiritual communion."[32] On the fifth day of every week they would meet in a different home and would discuss any issues "as he felt the need, all 'humbly and with a teachable heart not with any mind of cavilling or contradicting.'"[32][14]

After they became acquainted with one another, they asked if "they, as a collection of Christian strangers in the wilderness, have any right to assemble with the intention of establishing a church?"[33] Their understanding of the Bible led them to believe that they did, and so they continued to establish a church based on Christian love, but also one that had requirements for membership. In order to achieve a "further union", they determined the church must "convey unto us all the ordinances of Christ's instituted worship, both because it is the command of God... and because the spiritual condition of every Christian is such as stand in need of all instituted ordinances for the repair of the spirit."[33]

Only 'visible saints' were pure enough to become members.[14] A public confession of faith was required, as was a life of holiness.[34][14] A group of the most pious men interviewed all who sought admission to the church.[14] All others would be required to attend the sermons at the meeting house, but could not join the church, nor receive communion, be baptized or become an officer of the church.[34]

Finally, on November 8, 1638, two years after the incorporation of the town and one year after the first church meetings were held, the covenant was signed and the church was gathered.[35][14] Guests from other towns were invited for the event as they sought the "advice and counsel of the churches" and the "countenance and encouragement of the magistrates."[35][14] A "tender" search for a minister took an additional several months, and finally John Allin was ordained as pastor and John Hunting as Ruling Elder.[1][36] Both men had been among the 8 found worthy enough to be the first members of the church and to first sign the covenant.[35] As in England, Puritan ministers in the American colonies were usually appointed to the pulpits for life[37] and Allin served for 32 years.[3]

By 1648, 70% of the men and many of their wives, and in some cases the wives only, had become members of the Church.[38][14] Between the years of 1644 and 1653, 80% of children born in town were baptized, indicating that at least one parent was a member of the church. Servants and masters, young and old, rich and poor alike all joined the church.[38]

A few decades after founding the Church, however, the number of young people joining was in decline and by 1660 a future could be seen when a minority of residents were members.[16] At the insistence of the ministers of the church, a "halfway covenant" was adopted were children of members could become members, although would not be allowed to receive communion.[16]

The Town grows

In early years each resident was cautioned to keep a ladder handy in case that he may need to put out a fire on his thatched roof or climb out of harm's way should there be an attack from the Indians. It was also decreed that if any man should tie his horse to the ladder against the meetinghouse then he would be fined sixpence[3] and occasionally "found it necessary to institute fines against those caught borrowing another's canoe without permission or cutting down trees on the common land."[15]

Land distribution

The first settlers obtained title to the land from the Wampanoag people in the area, and began parceling out tracts of land.[14] They did so sparingly, however, and gave no family more land than they could currently improve.[14] Married men received 12 acres, while single men received eight.[39] Twenty years after it was founded, only 3% of the land had been distributed, with the rest being retained by the Town.[14] In 1657 there was still 125,000 acres remaining to be distributed to settlers.[16]

Land and animals

The grant from the colony gave them over "two hundred square miles of virgin wilderness, complete with lakes, hills, forests, meadows, Indians, and a seemingly endless supply of rocks and wolves."[1] Aside from "several score Indians, who were quickly persuaded to relinquish their claims for a small sum, the area was free of human habitation."[2] The original grant stretched from the border of Boston to the Rhode Island border.[2] It included the present-day communities of Natick, Wellesley, Needham, Dover, Westwood, Norwood, Walpole, Medfield, Millis, Medway, Norfolk, Franklin, Bellingham, Wrentham, and Plainville.[40] Early settlers gave places names such as Dismal Swamp, Purgatory Brook, Satan's Kingdom, and Devil's Oven.[40]

Wild animals were an issue, and the town placed a bounty on several of them. Upon producing an inch and a half of a rattlesnake, plus the rattle, the killer was entitled to six pence.[41] Other bounties were placed on wolves, which were frequently paid, as well as on wildcats.[41] In March 1639, 17-year-old John Dwight disappeared near Wigwam Pond, an area known to be particularly infested with wolves.[41] A 20 shilling bounty per bobcat was established in 1734, and the last person to claim it did so in 1957.[42]

In 1654, Town Meeting voted to dig a 4000' ditch connecting the Charles River at either end of its great loop.[4] Doing so created an island, today the neighborhood of Riverdale, and allowed the "Broad meadow" that was then there to more easily drain away the flood waters that gathered every spring.[4]

Jonathan Fairbanks

In 1637 Jonathan Fairbanks signed the town Covenant and was allotted 12 acres (49,000 m2) of land to build his home, which today is the oldest house in North America. In 1640 "the selectmen provided that Jonathan Fairbanks 'may have one cedar tree set out unto him to dispose of where he will: In consideration of some special service he hath done for the towne.'"[43] He had "long stood off from the church upon some scruples about public profession of faith and the covenant, yet after divers loving conferences..., he made such a declaration of his faith and conversion to God and profession of subjection to the ordinances of Christ in the church that he was readily and gladly received by the whole church."[38]

The house is still owned by the Fairbanks family and today stands at 511 East Street, on the corner of Whiting Ave, and near the site of the Old Avery Oak Tree. The builders of the USS Constitution once offered $70 to buy the tree, but the owner would not sell.[44] The Avery Oak, which was over 16' in circumference, survived the New England Hurricane of 1938 to be toppled by a violent thunderstorm in 1973; the Town Meeting Moderator's gavel was carved out of it.

Jonathan Fairbanks would have a number of notable descendants including murderer Jason Fairbanks of the famous Fairbanks case, as well as Presidents William H. Taft,[45] George H.W. Bush,[46] George W. Bush[47] and Vice President Charles W. Fairbanks.[48] He is also an ancestor of the father and son Governors of Vermont Erastus Fairbanks and Horace Fairbanks,[49] the poet Emily Dickinson,[50] and the anthropologist Margaret Mead.[51]

Wealth, population, and new towns

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1640 | >200[22] |

| 1648 | ~450[52] |

| 1686 | <600[53] |

| 1700 | 700[22] - >750[52] |

| 1736 | 1,200[53] |

| 1750 | 1,500[22] |

| 1765 | 1,919[54] |

| 1801 | 2,000[55] |

With a small population, a simple and agrarian economy, and the free distribution of large tracts of land, there was very little disparity in wealth. The servants in town "amounted to less than five percent of the population and were nearly all captive Indians, Negro slaves (of whom there were very few), or young children serving in another family as part of their upbringing."[56] The 5% of men who paid the highest taxes only owned 15% of the property. In contrast, the wealthiest 5% of men in nearby Boston controlled 25% of that town's wealth.[57] As the population grew disparities in wealth became apparent and "a permanent group of dependent poor began to appear" in the 1700s[22]

As the town's population grew greater and greater numbers of residents moved further away from the center of town. Until 1682 all Dedhamites had lived within 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of the meetinghouse.[22] As the numbers further away grew they began to break off and form new towns beginning with Medfield in 1651 and followed by Needham in 1711, Bellingham in 1719 and Walpole in 1724. As the population spread the residents crossed borders into other towns and between 1738 and 1740 Dedham annexed about eight square miles from Dorchester and Stoughton.[22] In the 1650s the Reverend John Eliot and the "praying Indians" won a lengthy court battle and were awarded the title to the 2,000 acres (8 km²) of land in the town now known as Natick.[1] Other towns would break away on their own, and some of them would further subdivide after that giving Dedham the designation "Mother of Towns."[6]

Despite the splits of other towns, the population of Dedham grew to more than ten times its original size by the end of the 18th century.

The 1700s

In the 1700s, Town Meeting began to assert more authority and fewer decisions were left to the judgment of the selectmen.[22]

Eleven Acadians arrived in Dedham in 1758 after the British deported them from what is today Nova Scotia. Though they were Catholics, the officially Protestant town accepted them and they "were allowed harbor in town as 'French Neutrals.'"[58] There would be no Catholic Church in Dedham for another 99 years when the first St. Mary's Church opened.

A legend first published in 1932 by William Moore tells the story of Black Bear, a descendant of King Phillip, who allegedly haunts the woods surrounding Wigwam Pond. According to the legend, Black Bear was a petty thief who one night in 1775 tried to kidnap the infant child of Sam Stone, a local farmer. Earlier in the day Stone had thwarted Black Bear's attempt to steal some horse blankets, and Black Bear took the child as revenge. When the child's cry awoke his parents, however, Stone gave chase.[59]

Black Bear eventually dropped the child in the woods so he could run faster to his waiting canoe. When Stone arrived on shore, he shot Black Bear, who gave out a loud cry and then fell into the pond. His spirit still allegedly haunts the area, and is sometimes seen holding a child, and other times with horse blankets, but always giving off an unearthly wail. The part of the pond that never freezes, even in the coldest winters, is said to be the spot where he died.[59]

American Revolution

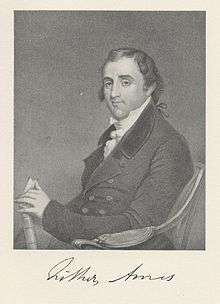

In the years leading to the American Revolution Dedham had a number of men rise to protect the liberties of the colonists. When Governor Edmund Andros was deposed and arrested in 1689 it was Dedham's Daniel Fisher who "burst into [John] Usher's house, to drag forth the tyrant by the collar, to bind him and cast him into a fort" and eventually send him back to England to stand trial.[3] Fisher also served, along with John Fairbanks, as town explorers and together selected 8,000 acres (32 km²) in Pocumtuck in place of the land given to Elliot and the praying Indians.[3] Fisher was the great-grandfather of Fisher Ames, Dedham resident and member of the First, Second, Third and Fourth Congresses.

In 1766 Dr. Nathaniel Ames, Fisher Ames' father, and the Sons of Liberty erected the Pillar of Liberty on the Church green at the Corner of High and Court streets. It is the only monument known to have been erected by the Sons of Liberty. On top of the 10' pillar was a bust of William Pitt the Younger who, according to the inscription on the granite base, "saved America from impending slavery, and confirmed our most loyal affection to King George III by procuring a repeal of the Stamp Act."[60] The monument was later destroyed.[3]

The Woodward Tavern stood diagonal from the monument on September 6, 1774. It was at the tavern, where the Norfolk County Superior Court now stands, that the Suffolk Convention convened and eventually adopted the Suffolk Resolves. The resolves were then rushed by Paul Revere to the First Continental Congress. The Congress in turn adopted as a precursor to the Declaration of Independence. The resolves denounced the Intolerable Acts as "gross infractions of those rights to which we are justly entitled by the laws of nature, the British constitution, and the charter of the province" and called on the towns to organize militias to protect "the rights of the people."[61] In 1774, the year after the Boston Tea Party, the Town outlawed India tea and appointed a committee to publish the names of any resident caught drinking it.[62]

On the morning of April 19, 1775, a messenger came "down the Needham road" with news about the battle in Lexington. A Dedham resident, "Captain Joseph Guild 'gagged a croaker' who said the news was false and in an hour"[3] the "men of Dedham, even the old men, received their minister's blessing and went forth, in such numbers that scarce one male between sixteen and seventy was left at home."[64] Aaron Guild, a captain in the British Army during the French and Indian War, was plowing his fields in South Dedham (today Norwood) when he heard of the battle. He immediately "left plough in furrow [and] oxen standing" to set forth for the conflict, arriving in time to fire upon the retreating British.[65]

Nearly every man who was physically able joined Guild and a majority served in the siege of Boston. The Continental Army issued the town a quota as the war progressed but as the town had already run through its available men it was forced to hire mercenaries from Boston.[1] The population at the time was between 1,500 and 2,000 persons, of which 672 men fought in the Revolution and 47 did not return.[5]

As the Revolutionary War went on the attention of the General Court, which had resolved itself into a Provincial Congress in 1774, focused primarily on military matters.[66] The town was then forced to develop a government that operated with increasing independence from the province. The Dedham men who would become American leaders in the first years of independence from the British crown, including "Reverend Jason Haven, the younger Nathaniel Ames, his brother Fisher, and the Samuel Dexters (father and son) all received their political indoctrinations in Dedham during this period of turmoil and change."[1] Following the evacuation of Boston General George Washington spent the night of April 4, 1776 at Samuel Dexter's home on his way to New York.[44] The house still stands today at 699 High Street.[67]

Firsts

While both the Charles River and the Neponset River ran through Dedham and close by to one another, both were slow moving and could not power a mill. With an elevation difference of 40 feet (12 m) between the two, however, a canal connecting them would be swift moving. In 1639 the town ordered that a 4000' ditch be dug between the two so that one third of the Charles' water would flow down what would become known as Mother Brook and into the Neponset. Abraham Shaw would begin construction of the first dam and mill on the Brook in 1641 and it would be completed by John Elderkin, who later built the first church in New London, Connecticut.[3]

On January 1, 1644, by unanimous vote, Dedham authorized the first U.S. taxpayer-funded public school; "the seed of American education."[68] Its first teacher, Rev. Ralph Wheelock, was paid 20 pounds annually to instruct the youth of the community. Descendants of these students would become presidents of Dartmouth College, Yale University and Harvard University. Another early teacher, Michaell Metcalfe, was one of the town's first residents and a signer of the Covenant. At the age of 70 he began teaching reading in the school[69] and in 1652 purchased a joined armchair that is today the oldest dated piece of American furniture.[8][70]

John Thurston was commission by the town to build the first schoolhouse in 1648 for which he received a partial payment of £11.0.3 on December 2, 1650. The details in the contract require him to construct floorboards, doors, and "fitting the interior with 'featheredged and rabbited' boarding" similar to that found in the Fairbanks House.[8]

Notes

- ↑ The third paragraph of the Town Covenant stated that "That if at any time differences shall rise between parties of our said town, that then such party or parties shall presently refer all such differences unto some one, two or three others of our said society to be fully accorded and determined without any further delay, if it possibly may be."[13][16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "A Capsule History of Dedham". Dedham Historical Society. 2006. Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- 1 2 3 Lockridge 1985, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Abbott 1903, pp. 290-297.

- 1 2 3 Parr 2009, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Rev. Elias Nason (1890). "A Gazetteer of the State of Massachusetts". CapeCodHistory.us. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- 1 2 "A Brief History of Norwood". Town of Norwood, Massachusetts. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- 1 2 Mansbridge 1980, p. 130.

- 1 2 3 St. George, Robert Blair (1979). "Style and Structure in the Joinery of Dedham and Medfield, Massachusetts, 1635-1685". Winterthur Portfolio. Henry Francis DuPont Winterthur Museum. 13: 1–46. ISSN 1545-6927. JSTOR 1180600 – via JSTOR. (registration required (help)).

- 1 2 Hill, Don Gleason (1892). The Early Records of the Town of Dedham, Massachusetts 1636 - 1659, The Dedham Transcript, Vol. 3. Dedham, Massachusetts.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985.

- ↑ Brown & Tager 2000, p. 37.

- 1 2 Lockridge 1985, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Dedham Covenant". A Puritan's Mind. 1636. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Brown & Tager 2000, p. 38.

- 1 2 Mansbridge 1980, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Brown & Tager 2000, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 Lockridge 1985, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 Lockridge 1985, p. 47.

- 1 2 Mansbridge 1980, p. 131.

- 1 2 Mansbridge 1980, p. 352.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 48.

- 1 2 Lockridge 1985, p. 40.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 41.

- 1 2 Lockridge 1985, p. 42.

- ↑ Mansbridge 1980, p. 133.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 32.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 44.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 46.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 45.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 22.

- 1 2 Lockridge 1985, p. 25.

- 1 2 Lockridge 1985, p. 26.

- 1 2 Lockridge 1985, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Lockridge 1985, p. 29.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 30.

- ↑ Friedman, Benjamin M. (2005). The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Lockridge 1985, p. 31.

- ↑ "Questions We Are Often Asked". Dedham Historical Society News-Letter (May): 3–4. 2015.

- 1 2 Parr 2009, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 Parr 2009, p. 12.

- ↑ Parr 2009, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Miles, D H, Worthington, M J, and Grady, A A (2002). "Development of Standard Tree-Ring Chronologies for Dating Historic Structures in Eastern Massachusetts Phase II". Boston Dendrochronology Project. Oxford Dendrochronology Laboratory. Archived from the original on January 3, 2005. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- 1 2 Guide Book To New England Travel. 1919.

- ↑ Lineage as follows: Jonathan (b. 1595) to his son George (b. 1619) to his daughter Mary who married Joseph Daniels and together they had a son Eleazer (b. 1681). It continues through his son David to his daughter Cloe who married Seth Davenport and together had a child Anna. Anna married William Torrey whose son Samuel had a daughter Louisa. Louisa married Alphonso Taft and together they had President William Howard Taft.

- ↑ Lineage as follows: Jonathan (b. 1595) to his son Jonathan (b. 1628) to his son Jeremiah (b. 1674) to his daughter Mary who married Richard Bush and together had Timothy Bush (b. 1728). The lineage continues with Timothy's son Timothy Bush, Jr. (b. 1761) to his son Obadiah Newcomb Bush(b. 1791) to his son James Smith Bush (b. 1825) to his son Samuel P. Bush (b. 1863) to his son Senator Prescott Bush who was George Bush's father.

- ↑ Lineage as follows: Jonathan (b. 1595) to his son Jonathan (b. 1628) to his son Jeremiah (b. 1674) to his daughter Mary who married Richard Bush and together had Timothy Bush (b. 1728). The lineage continues with Timothy's son Timothy Bush, Jr. (b. 1761) to his son Obadiah Newcomb Bush(b. 1791) to his son James Smith Bush (b. 1825) to his son Samuel P. Bush (b. 1863) to his son Senator Prescott Bush to his son President George H. W. Bush who was George W. Bush's father.

- ↑ Lineage as follows: Jonathan to his son Jonas to his son Jabez to his son Joshua to his son Luther to his son Luther to his son Loriston Monroe who was the father of Vice President Charles Warren Fairbanks.

- ↑ Lineage as follows: Jonathan to his son John to his son Joseph to his son Joseph to his son Ebenezer to his son Joseph to his son Governor Erastus Fairbanks to his son Governor Horace Fairbanks.

- ↑ Lineage as follows: Jonathan to his son George to his son Eliesur to his son Eliesur to his son Eleazer to his daughter Sarah who married Jude Fay to their daughter Betsey who married Joel Norcross to their daughter Emily who married Edward Dickinson and their child was Emily Dickinson.

- ↑ Lineage as follows: Jonathan to his son George to his son Eliesur to his daughter Martha who married Ebenezer Leland, and together they had a child Caleb whose daughter Hannah married John Ware. Their son Orlando had a daughter Emily who married James Pecker Fogg, who had a son James Leland Fogg. He married Elizabeth Bogart Lockwood and they had a daughter Emily Fogg who married Edward Sherwood Mead. Together their child was Margaret Mead.

- 1 2 Lockridge 1985, p. 65.

- 1 2 Lockridge 1985, p. 94.

- ↑ Worthington, Erastus (1827). The History of Dedham: From the beginning of Its Settlement in September, 1635 to May 1827. Boston: Dutton and Wentworth. p. 65.

- ↑ Sean Murphy. "Historian recalls the Fairbanks case, Dedham's first big trial". Daily News Transcript. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 72.

- ↑ Lockridge 1985, p. 73.

- ↑ "St. Mary's Community Parish History". St. Mary's Parish. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- 1 2 Parr 2009, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Translated from the Latin: "Laus Deo Regi et Imunitatm/ Autoribusq, maxime Patrono/ Pitt, qui Rempub. rursum evulsit/ Faucibus Orch."

- ↑ Suffolk County Convention (1774). "Suffolk Resolves". Constitution Society. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ↑ The Genealogical History of Dover, Massachusetts, Frank Smith]

- ↑ Peter Schworm (2006-10-01). "He was a patriot, not a redcoat". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ↑ David Gibbs, Jr.; Jerry Newcombe (April 19, 2008). "A Pastor's Role at Lexington". One Nation Under God: Ten Things Every Christian Should Know About the Founding of America. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ From the Aaron Guild Memorial Stone, dedicated in 1903, which stands outside the Norwood public library and reads: "Near this spot/ Capt. Aaron Guild/ On April 19, 1775/ left plow in furrow, oxen standing/ and departing for Lexington/ arrived in time to fire upon/ the retreating British".

- ↑ "Historical Sketch – Provincial Congresses (1774-1775)". Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ↑ Robert Hanson (1999). "Stories Behind the Pictures in the Images of America: Dedham Book". Dedham Historical Society News-Letter (December). Archived from the original on December 31, 2006.

- ↑ Maria Sacchetti (2005-11-27). "Schools vie for honor of being the oldest". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ Jennifer Monaghan. "Literacy instruction and the town school in seventeenth-century New England". University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ↑ "Collections". Dedham Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 9, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

Works cited

- Mansbridge, Jane J. (1980). Beyond Adversary Democracy. New York: Basic Books.

- Abbott, Katharine M. (1903). Old Paths And Legends Of New England (PDF). New York: The Knickerbocker Press. pp. 290–297.

- Lockridge, Kenneth (1985). A New England Town. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 4. ISBN 0-393-95459-5.

- Brown, Richard D.; Tager, Jack (2000). Massachusetts: A concise history. University of Massachusetts Press.

- Parr, James L. (2009). Dedham: Historic and Heroic Tales From Shiretown. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-750-0.