Horseshoe crab

| Limulidae Temporal range: Ordovician–Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Limulus polyphemus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Merostomata |

| Order: | Xiphosura |

| Family: | Limulidae Leach, 1819 [1] |

| Genera | |

Horseshoe crabs are marine arthropods of the family Limulidae and order Xiphosura or Xiphosurida, that live primarily in and around shallow ocean waters on soft sandy or muddy bottoms. They occasionally come onto shore to mate. They are commonly used as bait and in fertilizer. In recent years, a decline in the population has occurred as a consequence of coastal habitat destruction in Japan and overharvesting along the east coast of North America. Tetrodotoxin may be present in the roe of species inhabiting the waters of Thailand.[2] Because of their origin 450 million years ago (Mya), horseshoe crabs are considered living fossils.[3]

Classification

Horseshoe crabs superficially resemble crustaceans. They belong to a separate subphylum, Chelicerata, and are closely related to arachnids.[4] The earliest horseshoe crab fossils are found in strata from the late Ordovician period, roughly 450 million years ago.

The Limulidae are the only recent family of the order Xiphosura, and contain all four living species of horseshoe crabs:[1]

- Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, the mangrove horseshoe crab, found in Southeast Asia

- Limulus polyphemus, the Atlantic horseshoe crab, found along the American Atlantic coast and in the Gulf of Mexico

- Tachypleus gigas, found in Southeast and East Asia

- Tachypleus tridentatus, found in Southeast and East Asia

Anatomy and behavior

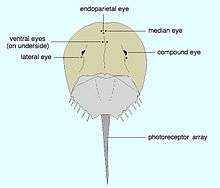

The entire body of the horseshoe crab is protected by a hard carapace. It has two compound lateral eyes, each composed of about 1,000 ommatidia, plus a pair of median eyes that are able to detect both visible light and ultraviolet light, a single endoparietal eye, and a pair of rudimentary lateral eyes on the top. The latter become functional just before the embryo hatches. Also, a pair of ventral eyes is located near the mouth, as well as a cluster of photoreceptors on the telson. Despite having a relatively poor eyesight, the animals have the largest rods and cones of any known animal, about 100 times the size of humans',[5][6] and their eyes are a million times more sensitive to light at night than during the day.[7] The mouth is located in the center of the legs, whose bases are referred to as gnathobases and have the same function as jaws and help grind up food. The horseshoe crab has five pairs of legs for walking, swimming, and moving food into the mouth, each with a claw at the tip, except for the last pair. The long, straight, rigid tail can be used to flip the animal over if turned upside down, so a horseshoe crab with a broken tail is susceptible to desiccation or predation.

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Behind its legs, the horseshoe crab has book gills, which exchange respiratory gases, and are also occasionally used for swimming. As in other arthropods, a true endoskeleton is absent, but the body does have an endoskeletal structure made up of cartilaginous plates that support the book gills.[8] They are more often found on the ocean floor searching for worms and molluscs, which are their main food. They may also feed on crustaceans and even small fish.

Females are larger than males; C. rotundicauda is the size of a human hand, while L. polyphemus can be up to 60 cm (24 in) long (including tail). The juveniles grow about 33% larger with every molt until reaching adult size.[9]

Breeding

During the breeding season, horseshoe crabs migrate to shallow coastal waters. A male selects a female and clings to her back. Often, several males surround the female and all fertilize together which makes it easy to spot and count females as they are the large center carapace surrounded by 3-5 smaller ones. The female digs a hole in the sand and lays her eggs while the male(s) fertilize them. The female can lay between 60,000 and 120,000 eggs in batches of a few thousand at a time. The eggs take about two weeks to hatch; shore birds eat many of them before they hatch. The larvae molt six times during the first year.[15] Raising horseshoe crabs in captivity has proven to be difficult. Some evidence indicates mating takes place only in the presence of the sand or mud in which the horseshoe crab's eggs were hatched. It is not known with certainty what is in the sand that the crab can sense, nor how they sense it.[16]

Blood

Unlike vertebrates, horseshoe crabs do not have hemoglobin in their blood, but instead use hemocyanin to carry oxygen. Because of the copper present in hemocyanin, their blood is blue. Their blood contains amebocytes, which play a role similar to white blood cells of vertebrates in defending the organism against pathogens. Amebocytes from the blood of L. polyphemus are used to make Limulus amebocyte lysate, which is used for the detection of bacterial endotoxins in medical applications. The blood of horseshoe crabs is harvested for this purpose.[17]

Harvesting horseshoe crab blood involves collecting and bleeding the animals, and then releasing them back into the sea. Most of the animals survive the process; mortality is correlated with both the amount of blood extracted from an individual animal, and the stress experienced during handling and transportation.[18] Estimates of mortality rates following blood harvesting vary from 3-15%[19] to 10-30%.[20]

Threats

Fishery

Horseshoe crabs are used as bait to fish for eels (mostly in the United States) and whelk, or conch. However, fishing with horseshoe crab is temporarily forbidden in New Jersey (moratorium on harvesting) and restricted to males in Delaware. A permanent moratorium is in effect in South Carolina.[21] The eggs are eaten in parts of Southeast Asia and China.[22]

A low horseshoe crab population in the Delaware Bay is hypothesized to endanger the future of the red knot. Red knots, long-distance migratory shorebirds, feed on the protein-rich eggs during their stopovers on the beaches of New Jersey and Delaware.[23] An effort is ongoing to develop adaptive-management plans to regulate horseshoe crab harvests in the bay in a way that protects migrating shorebirds.[24]

Shoreline development

Development along shorelines is dangerous to horseshoe crab spawning, limiting available space and degrading habitat. Bulkhead can block access to intertidal spawning regions as well.[25]

References

- 1 2 Kōichi Sekiguchi (1988). Biology of Horseshoe Crabs. Science House. ISBN 978-4-915572-25-8.

- ↑ Attaya Kungsuwan; Yuji Nagashima; Tamao Noguchi; et al. (1987). "Tetrodotoxin in the Horseshoe Crab Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda Inhabiting Thailand" (pdf). Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi. 53 (2): 261–266. doi:10.2331/suisan.53.261.

- ↑ David Sadava; H. Craig Heller; David M. Hillis; May Berenbaum (2009). Life: the Science of Biology (9th ed.). W. H. Freeman. p. 683. ISBN 978-1-4292-1962-4.

- ↑ Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason A. (2014). "Three-dimensional reconstruction and the phylogeny of extinct chelicerate orders". PeerJ. 2: e641. doi:10.7717/peerj.641. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ↑ Anatomy: Vision - The Horseshoe Crab

- ↑ Horseshoe Crab, Limulus polyphemus ~ MarineBio.org

- ↑ The Extreme Life of the Sea

- ↑ The biology of cartilage. I. Invertebrate cartilages: Limulus gill cartilage

- ↑ Lesley Cartwright-Taylor; Julian Lee; Chia Chi Hsu (2009). "Population structure and breeding pattern of the mangrove horseshoe crab Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda in Singapore" (PDF). Aquatic Biology. 8 (1): 61–69. doi:10.3354/ab00206.

- ↑ Manton SM (1977) The Arthropoda: habits, functional morphology, and evolution Page 57, Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Shuster CN, Barlow RB and Brockmann HJ (Eds.) (2003) The American Horseshoe Crab Pages 163–164, Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674011595.

- ↑ Vosatka ED (1970) "Observations on the swimming, righting, and burrowing movements of young horseshoe crabs, Limulus polyphemus" Ohio Journal of Science, 70 (5): 276–283. pdf

- ↑ Battelle, B.A. (2006), "The eyes of Limulus polyphemus (Xiphosura, Chelicerata) and their afferent and efferent projections.", Arthropod Structure & Development, 35 (4): 261–74, doi:10.1016/j.asd.2006.07.002, PMID 18089075.

- ↑ Barlow RB (2009) "Vision in horseshoe crabs" Pages 223–235 in JT Tanacredi, ML Botton and D Smith, Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs, Springer. ISBN 9780387899589.

- ↑ 23rd September 2014. "The Rabbit and the Horse Shoe Crab". Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ David Funkhouser (April 15, 2011). "Crab love nest". Scientific American. 304 (4): 29. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0411-29.

- ↑ http://www.horseshoecrab.org/med/med.html

- ↑ Lenka Hurton (2003). Reducing post-bleeding mortality of horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) used in the biomedical industry (PDF) (M.Sc. thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- ↑ "Crash: A Tale of Two Species – The Benefits of Blue Blood", PBS

- ↑ The Blood Harvest The Atlantic, 2014.

- ↑ "Horseshoe crab". SC DNR species gallery. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ 大西一實. "Vol.56 食うか食われるか?". あくあは〜つ通信. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ↑ "Red knots get to feast on horseshoe crab eggs". Environment News Service. March 26, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ↑ October 26, 2011. "Critter Class Hodge Podge (Horseshoe crabs and Wooly Bears)" (PDF). The Wildlife Center. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ "Conservation". ERDG. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

Further reading

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "King-Crab". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "King-Crab". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

Media related to Limulidae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Limulidae at Wikimedia Commons

- LAL Update

- Science Friday Video: horseshoe crab season

- Horseshoe crab at the Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- The Horseshoe Crab – Medical Uses; The Ecological Research & Development Group (ERDG)

- RedKnot.org links to shorebird recovery sites, movies, events & other info on Red Knot rufa & horseshoe crabs.

- Crab Bleeders Article about the men who bleed horseshoe crabs for science.

- Day time mating of horseshoe crabs in Maine