Innovation

Innovation is defined simply as a "new idea, device, or method".[1] However, innovation is often also viewed as the application of better solutions that meet new requirements, unarticulated needs, or existing market needs.[2] This is accomplished through more-effective products, processes, services, technologies, or business models that are readily available to markets, governments and society. The term "innovation" can be defined as something original and more effective and, as a consequence, new, that "breaks into" the market or society.[3] It is related to, but not the same as, invention.[4]

While a novel device is often described as an innovation, in economics, management science, and other fields of practice and analysis, innovation is generally considered to be the result of a process that brings together various novel ideas in a way that they affect society. In industrial economics, innovations are created and found empirically from services to meet the growing consumer demand.[5][6][7]

Definition

In a survey of literature on innovation, Edison et al.[8] found over 40 definitions. They also performed an industrial survey to capture how innovation is defined in the software industry. After analysis of the existing definitions whether these definitions comprehensively cover all the dimensions of innovation, they found the following definition to be the most complete:

Innovation is: production or adoption, assimilation, and exploitation of a value-added novelty in economic and social spheres; renewal and enlargement of products, services, and markets; development of new methods of production; and establishment of new management systems. It is both a process and an outcome.

This definition was given by Crossan and Apaydin and it builds on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) manual's definition.

Edison et al.[8] also found two interesting dimensions of innovation including: degree of novelty (i.e. whether an innovation is new to the firm, new to the market, new to the industry, and new to the world) and type of innovation (whether it is process or product/service innovation).

Inter-disciplinary views

Business and economics

In business and economics, innovation can be a catalyst to growth. With rapid advancements in transportation and communications over the past few decades, the old world concepts of factor endowments and comparative advantage which focused on an area’s unique inputs are outmoded for today’s global economy. Economist Joseph Schumpeter, who contributed greatly to the study of innovation economics, argued that industries must incessantly revolutionize the economic structure from within, that is innovate with better or more effective processes and products, as well as market distribution, such as the connection from the craft shop to factory. He famously asserted that "creative destruction is the essential fact about capitalism".[9] In addition, entrepreneurs continuously look for better ways to satisfy their consumer base with improved quality, durability, service, and price which come to fruition in innovation with advanced technologies and organizational strategies.[10]

One prime example was the explosive boom of Silicon Valley startups out of the Stanford Industrial Park. In 1957, dissatisfied employees of Shockley Semiconductor, the company of Nobel laureate and co-inventor of the transistor William Shockley, left to form an independent firm, Fairchild Semiconductor. After several years, Fairchild developed into a formidable presence in the sector. Eventually, these founders left to start their own companies based on their own, unique, latest ideas, and then leading employees started their own firms. Over the next 20 years, this snowball process launched the momentous startup company explosion of information technology firms. Essentially, Silicon Valley began as 65 new enterprises born out of Shockley’s eight former employees.[11] Since then, hubs of innovation have sprung up globally with similar metonyms, including Silicon Alley encompassing New York City.

Organizations

In the organizational context, innovation may be linked to positive changes in efficiency, productivity, quality, competitiveness, and market share. However, recent research findings highlight the complementary role of organizational culture in enabling organizations to translate innovative activity into tangible performance improvements.[12] Organizations can also improve profits and performance by providing work groups opportunities and resources to innovate, in addition to employee's core job tasks.[13] Peter Drucker wrote:

Innovation is the specific function of entrepreneurship, whether in an existing business, a public service institution, or a new venture started by a lone individual in the family kitchen. It is the means by which the entrepreneur either creates new wealth-producing resources or endows existing resources with enhanced potential for creating wealth. –Drucker[14]

According to Clayton Christensen, disruptive innovation is the key to future success in business.[15] The organisation requires a proper structure in order to retain competitive advantage. It is necessary to create and nurture an environment of innovation. Executives and managers need to break away from traditional ways of thinking and use change to their advantage. It is a time of risk but even greater opportunity.[16] The world of work is changing with the increase in the use of technology and both companies and businesses are becoming increasingly competitive. Companies will have to downsize and re-engineer their operations to remain competitive. This will affect employment as businesses will be forced to reduce the number of people employed while accomplishing the same amount of work if not more.[17]

All organizations can innovate, including for example hospitals, universities, and local governments.[18] For instance, former Mayor Martin O’Malley pushed the City of Baltimore to use CitiStat, a performance-measurement data and management system that allows city officials to maintain statistics on crime trends to condition of potholes. This system aids in better evaluation of policies and procedures with accountability and efficiency in terms of time and money. In its first year, CitiStat saved the city $13.2 million.[19] Even mass transit systems have innovated with hybrid bus fleets to real-time tracking at bus stands. In addition, the growing use of mobile data terminals in vehicles, that serve as communication hubs between vehicles and a control center, automatically send data on location, passenger counts, engine performance, mileage and other information. This tool helps to deliver and manage transportation systems.[20]

Still other innovative strategies include hospitals digitizing medical information in electronic medical records. For example, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's HOPE VI initiatives turned severely distressed public housing in urban areas into revitalized, mixed-income environments; the Harlem Children’s Zone used a community-based approach to educate local area children; and the Environmental Protection Agency's brownfield grants facilitates turning over brownfields for environmental protection, green spaces, community and commercial development.

Sources of innovation

There are several sources of innovation. It can occur as a result of a focus effort by a range of different agents, by chance, or as a result of a major system failure.

According to Peter F. Drucker, the general sources of innovations are different changes in industry structure, in market structure, in local and global demographics, in human perception, mood and meaning, in the amount of already available scientific knowledge, etc.[14]

In the simplest linear model of innovation the traditionally recognized source is manufacturer innovation. This is where an agent (person or business) innovates in order to sell the innovation.

Another source of innovation, only now becoming widely recognized, is end-user innovation. This is where an agent (person or company) develops an innovation for their own (personal or in-house) use because existing products do not meet their needs. MIT economist Eric von Hippel has identified end-user innovation as, by far, the most important and critical in his classic book on the subject, The Sources of Innovation.[21]

The robotics engineer Joseph F. Engelberger asserts that innovations require only three things:

- A recognized need,

- Competent people with relevant technology, and

- Financial support.[22]

However, innovation processes usually involve: identifying customer needs, macro and meso trends, developing competences, and finding financial support.

The Kline chain-linked model of innovation[23] places emphasis on potential market needs as drivers of the innovation process, and describes the complex and often iterative feedback loops between marketing, design, manufacturing, and R&D.

Innovation by businesses is achieved in many ways, with much attention now given to formal research and development (R&D) for "breakthrough innovations". R&D help spur on patents and other scientific innovations that leads to productive growth in such areas as industry, medicine, engineering, and government.[24] Yet, innovations can be developed by less formal on-the-job modifications of practice, through exchange and combination of professional experience and by many other routes. The more radical and revolutionary innovations tend to emerge from R&D, while more incremental innovations may emerge from practice – but there are many exceptions to each of these trends.

Information technology and changing business processes and management style can produce a work climate favorable to innovation.[25] For example, the software tool company Atlassian conducts quarterly "ShipIt Days" in which employees may work on anything related to the company's products.[26] Google employees work on self-directed projects for 20% of their time (known as Innovation Time Off). Both companies cite these bottom-up processes as major sources for new products and features.

An important innovation factor includes customers buying products or using services. As a result, firms may incorporate users in focus groups (user centred approach), work closely with so called lead users (lead user approach) or users might adapt their products themselves. The lead user method focuses on idea generation based on leading users to develop breakthrough innovations. U-STIR, a project to innovate Europe’s surface transportation system, employs such workshops.[27] Regarding this user innovation, a great deal of innovation is done by those actually implementing and using technologies and products as part of their normal activities. In most of the times user innovators have some personal record motivating them. Sometimes user-innovators may become entrepreneurs, selling their product, they may choose to trade their innovation in exchange for other innovations, or they may be adopted by their suppliers. Nowadays, they may also choose to freely reveal their innovations, using methods like open source. In such networks of innovation the users or communities of users can further develop technologies and reinvent their social meaning.[28][29]

Goals and failures

Programs of organizational innovation are typically tightly linked to organizational goals and objectives, to the business plan, and to market competitive positioning. One driver for innovation programs in corporations is to achieve growth objectives. As Davila et al. (2006) notes, "Companies cannot grow through cost reduction and reengineering alone... Innovation is the key element in providing aggressive top-line growth, and for increasing bottom-line results".[30]

One survey across a large number of manufacturing and services organizations found, ranked in decreasing order of popularity, that systematic programs of organizational innovation are most frequently driven by: Improved quality, Creation of new markets, Extension of the product range, Reduced labor costs, Improved production processes, Reduced materials, Reduced environmental damage, Replacement of products/services, Reduced energy consumption, Conformance to regulations.[30]

These goals vary between improvements to products, processes and services and dispel a popular myth that innovation deals mainly with new product development. Most of the goals could apply to any organisation be it a manufacturing facility, marketing firm, hospital or local government. Whether innovation goals are successfully achieved or otherwise depends greatly on the environment prevailing in the firm.[31]

Conversely, failure can develop in programs of innovations. The causes of failure have been widely researched and can vary considerably. Some causes will be external to the organization and outside its influence of control. Others will be internal and ultimately within the control of the organization. Internal causes of failure can be divided into causes associated with the cultural infrastructure and causes associated with the innovation process itself. Common causes of failure within the innovation process in most organizations can be distilled into five types: Poor goal definition, Poor alignment of actions to goals, Poor participation in teams, Poor monitoring of results, Poor communication and access to information.[32]

Diffusion

Diffusion of innovation research was first started in 1903 by seminal researcher Gabriel Tarde, who first plotted the S-shaped diffusion curve. Tarde defined the innovation-decision process as a series of steps that includes:[33]

- First knowledge

- Forming an attitude

- A decision to adopt or reject

- Implementation and use

- Confirmation of the decision

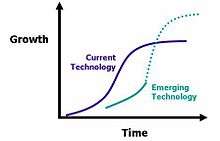

Once innovation occurs, innovations may be spread from the innovator to other individuals and groups. This process has been proposed that the life cycle of innovations can be described using the 's-curve' or diffusion curve. The s-curve maps growth of revenue or productivity against time. In the early stage of a particular innovation, growth is relatively slow as the new product establishes itself. At some point customers begin to demand and the product growth increases more rapidly. New incremental innovations or changes to the product allow growth to continue. Towards the end of its lifecycle, growth slows and may even begin to decline. In the later stages, no amount of new investment in that product will yield a normal rate of return

The s-curve derives from an assumption that new products are likely to have "product life" – i.e., a start-up phase, a rapid increase in revenue and eventual decline. In fact the great majority of innovations never get off the bottom of the curve, and never produce normal returns.

Innovative companies will typically be working on new innovations that will eventually replace older ones. Successive s-curves will come along to replace older ones and continue to drive growth upwards. In the figure above the first curve shows a current technology. The second shows an emerging technology that currently yields lower growth but will eventually overtake current technology and lead to even greater levels of growth. The length of life will depend on many factors.[34]

Measures

Edison et al.[8] in their review of literature on innovation management found 232 innovation metrics. They categorized these measures along five dimensions i.e. inputs to the innovation process, output from the innovation process, effect of the innovation output, measures to assess the activities in an innovation process and availability of factors that facilitate such a process.[8]

There are two different types of measures for innovation: the organizational level and the political level.

Organizational level

The measure of innovation at the organizational level relates to individuals, team-level assessments, and private companies from the smallest to the largest company. Measure of innovation for organizations can be conducted by surveys, workshops, consultants, or internal benchmarking. There is today no established general way to measure organizational innovation. Corporate measurements are generally structured around balanced scorecards which cover several aspects of innovation such as business measures related to finances, innovation process efficiency, employees' contribution and motivation, as well benefits for customers. Measured values will vary widely between businesses, covering for example new product revenue, spending in R&D, time to market, customer and employee perception & satisfaction, number of patents, additional sales resulting from past innovations.[35]

Political level

For the political level, measures of innovation are more focused on a country or region competitive advantage through innovation. In this context, organizational capabilities can be evaluated through various evaluation frameworks, such as those of the European Foundation for Quality Management. The OECD Oslo Manual (1995) suggests standard guidelines on measuring technological product and process innovation. Some people consider the Oslo Manual complementary to the Frascati Manual from 1963. The new Oslo manual from 2005 takes a wider perspective to innovation, and includes marketing and organizational innovation. These standards are used for example in the European Community Innovation Surveys.[36]

Other ways of measuring innovation have traditionally been expenditure, for example, investment in R&D (Research and Development) as percentage of GNP (Gross National Product). Whether this is a good measurement of innovation has been widely discussed and the Oslo Manual has incorporated some of the critique against earlier methods of measuring. The traditional methods of measuring still inform many policy decisions. The EU Lisbon Strategy has set as a goal that their average expenditure on R&D should be 3% of GDP.[37]

Indicators

Many scholars claim that there is a great bias towards the "science and technology mode" (S&T-mode or STI-mode), while the "learning by doing, using and interacting mode" (DUI-mode) is widely ignored. For an example, that means you can have the better high tech or software, but there are also crucial learning tasks important for innovation. But these measurements and research are rarely done.

A common industry view (unsupported by empirical evidence) is that comparative cost-effectiveness research (CER) is a form of price control which, by reducing returns to industry, limits R&D expenditure, stifles future innovation and compromises new products access to markets.[38] Some academics claim the CER is a valuable value-based measure of innovation which accords truly significant advances in therapy (those that provide "health gain") higher prices than free market mechanisms.[39] Such value-based pricing has been viewed as a means of indicating to industry the type of innovation that should be rewarded from the public purse.[40] The Australian academic Thomas Alured Faunce has developed the case that national comparative cost-effectiveness assessment systems should be viewed as measuring "health innovation" as an evidence-based concept distinct from valuing innovation through the operation of competitive markets (a method which requires strong anti-trust laws to be effective) on the basis that both methods of assessing innovation in pharmaceuticals are mentioned in annex 2C.1 of the AUSFTA.[41][42][43]

Rate of innovation

Innovation indices

Several indices attempt to measure innovation and rank entities based on these measures, such as:

- The Bloomberg Innovation Index

- The Bogota Manual, similar to the Oslo Manual, is focused on Latin America and the Caribbean countries.

- The Creative Class developed by Richard Florida

- The EIU Innovation Ranking

- The Global Competitiveness Report

- The Global Innovation Index (GII), by INSEAD[44]

- The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) Index

- The Innovation Capacity Index (ICI) published by a large number of international professors working in a collaborative fashion. The top scorers of ICI 2009–2010 were: 1. Sweden 82.2; 2. Finland 77.8; and 3. United States 77.5.[45]

- The Innovation Index, developed by the Indiana Business Research Center, to measure innovation capacity at the county or regional level in the United States.[46]

- The Innovation Union Scoreboard

- The Innovations Indikator

- The INSEAD Innovation Efficacy Index (aka the INSEAD Innovation Efficiency Index)[47]

- The International Innovation Index, produced jointly by The Boston Consulting Group (BCG), the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), and The Manufacturing Institute (MI) (the NAM's nonpartisan research affiliate), is a worldwide index measuring the level of innovation in a country. NAM describes it as the "largest and most comprehensive global index of its kind".

- The Management Innovation Index - Model for Managing Intangibility of Organizational Creativity: Management Innovation Index[48]

- The NYCEDC Innovation Index, by the New York City Economic Development Corporation, tracks New York City’s "transformation into a center for high-tech innovation. It measures innovation in the City’s growing science and technology industries and is designed to capture the effect of innovation on the City’s economy."[49]

- The Oslo Manual, similar to the Bogota Manual, is focused on North America, Europe, and other rich economies.

- The State Technology and Science Index, developed by the Milken Institute, is a U.S.-wide benchmark to measure the science and technology capabilities that furnish high paying jobs based around key components.[50]

- The World Competitiveness Scoreboard[51]

Innovation rankings

Many research studies try to rank countries based on measures of innovation. Common areas of focus include: high-tech companies, manufacturing, patents, post secondary education, research and development, and research personnel. The left ranking of the top 10 countries below is based on the 2016 Bloomberg Innovation Index.[52] However, studies may vary widely; for example the Global Innovation Index 2016 ranks Switzerland as number one wherein countries like South Korea and Japan do not even make the top ten.[53]

|

|

Future of innovation

Jonathan Huebner, a physicist working at the Pentagon's Naval Air Warfare Center, argued on the basis of both U.S. patents and world technological breakthroughs, per capita, that the rate of human technological innovation peaked in 1873 and has been slowing ever since.[54] In his article, he asked "Will the level of technology reach a maximum and then decline as in the Dark Ages?"[54] In later comments to New Scientist magazine, Huebner clarified that while he believed that we will reach a rate of innovation in 2024 equivalent to that of the Dark Ages, he was not predicting the reoccurrence of the Dark Ages themselves.[55]

His paper received some mainstream news coverage at the time.[56]

The claim has been met with criticism by John Smart, who asserted that research by technological singularity researcher Ray Kurzweil and others showed a "clear trend of acceleration, not deceleration" when it came to innovations.[57] The foundation issued a reply to Huebner in the pages of the journal his article was published in, citing the existence of Second Life and eHarmony as proof of accelerating innovation; Huebner also replied to this.[58] However, in 2010, Joseph A. Tainter, Deborah Strumsky, and José Lobo confirmed Huebner's findings using U.S. Patent Office data.[59] Additional verification was provided in a 2012 paper by Robert J. Gordon.[60]

Innovation and international development

The theme of innovation as a tool to disrupting patterns of poverty has gained momentum since the mid-2000s among major international development actors such as DFID,[61] Gates Foundation's use of the Grand Challenge funding model,[62] and USAID's Global Development Lab.[63] Networks have been established to support innovation in development, such as D-Lab at MIT.[64] Investment funds have been established to identify and catalyze innovations in developing countries, such as DFID's Global Innovation Fund,[65] Human Development Innovation Fund,[66] and (in partnership with USAID) the Global Development Innovation Ventures.[67]

Government policies

Given the noticeable effects on efficiency, quality of life, and productive growth, innovation is a key factor in society and economy. Consequently, policymakers have long worked to develop environments that will foster innovation and its resulting positive benefits, from funding Research and Development to supporting regulatory change, funding the development of innovation clusters, and using public purchasing and standardisation to 'pull' innovation through.

For instance, experts are advocating that the U.S. federal government launch a National Infrastructure Foundation, a nimble, collaborative strategic intervention organization that will house innovations programs from fragmented silos under one entity, inform federal officials on innovation performance metrics, strengthen industry-university partnerships, and support innovation economic development initiatives, especially to strengthen regional clusters. Because clusters are the geographic incubators of innovative products and processes, a cluster development grant program would also be targeted for implementation. By focusing on innovating in such areas as precision manufacturing, information technology, and clean energy, other areas of national concern would be tackled including government debt, carbon footprint, and oil dependence.[24] The U.S. Economic Development Administration understand this reality in their continued Regional Innovation Clusters initiative.[68] In addition, federal grants in R&D, a crucial driver of innovation and productive growth, should be expanded to levels similar to Japan, Finland, South Korea, and Switzerland in order to stay globally competitive. Also, such grants should be better procured to metropolitan areas, the essential engines of the American economy.[24]

Many countries recognize the importance of research and development as well as innovation including Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT);[69] Germany’s Federal Ministry of Education and Research;[70] and the Ministry of Science and Technology in the People's Republic of China. Furthermore, Russia's innovation programme is the Medvedev modernisation programme which aims at creating a diversified economy based on high technology and innovation. Also, the Government of Western Australia has established a number of innovation incentives for government departments. Landgate was the first Western Australian government agency to establish its Innovation Program.[71] The Cairns Region established the Tropical Innovation Awards in 2010 open to all businesses in Australia.[72] The 2011 Awards were extended to include participants from all Tropical Zone Countries.

Innovators

An innovator, in a general sense, is a person or an organization, who is one of the first to introduce into reality, something better than before. Something that opens up a new area for others, and achieves an innovation.

See also

- Communities of innovation

- Creative competitive intelligence

- Creative problem solving

- Creativity

- Disruptive innovation

- Theories of technology

- Deployment

- Diffusion (anthropology)

- Ecoinnovation

- List of countries by research and development spending

- List of emerging technologies

- List of Russian inventors

- Hype cycle

- Individual capital

- Induced innovation

- Information revolution

- Ingenuity

- Invention

- Innovation leadership

- Innovation management

- Innovation system

- Global Innovation Index (Boston Consulting Group)

- Global Innovation Index (INSEAD)

- Knowledge economy

- Multiple discovery

- Open Innovation

- Open Innovations (Forum and Technology Show)

- Outcome-Driven Innovation

- Participatory design

- Pro-innovation bias

- Public domain

- Research

- Sustainable Development Goals (Agenda 9)

- Technology Life Cycle

- Technological innovation system

- Timeline of historic inventions

- Toolkits for User Innovation

- Value network

- Virtual product development

- UNDP Innovation Facility

References

- ↑ "Innovation". Merriam-webster.com. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ Maryville, S (1992). "Entrepreneurship in the Business Curriculum". Journal of Education for Business. Vol. 68 No. 1, pp. 27–31.

- ↑ Based on Frankelius, P. (2009). "Questioning two myths in innovation literature". Journal of High Technology Management Research. Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 40–51.

- ↑ Bhasin, Kim (2012-04-02). "This Is The Difference Between 'Invention' And 'Innovation'". Business Insider.

- ↑ http://www.oecd.org/general/34749412.pdf

- ↑ http://www.oecd.org/berlin/45710126.pdf

- ↑ "EPSC - European Commission" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 Edison, H., Ali, N.B., & Torkar, R. (2013). "Towards innovation measurement in the software industry". Journal of Systems and Software 86(5), 1390–407. Available at: http://www.torkar.se/resources/jss-edisonNT13.pdf

- ↑ Schumpeter, J. A. (1943). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (6 ed.). Routledge. pp. 81–84. ISBN 0-415-10762-8.

- ↑ Heyne, P., Boettke, P. J., and Prychitko, D. L. (2010). The Economic Way of Thinking. Prentice Hall, 12th ed. pp. 163, 317–18.

- ↑ "Silicon Valley History & Future". Netvalley.com. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ Salge, T.O. & Vera, A. (2012). "Benefiting from Public Sector Innovation: The Moderating Role of Customer and Learning Orientation". Public Administration Review, Vol. 72, Issue 4, pp. 550–60.

- ↑ West, M. A. (2002). "Sparkling fountains or stagnant ponds: An integrative model of creativity and innovation implementation in work groups". Applied Psychology: An International Review, p. 424.

- 1 2 "The Discipline of Innovation". Harvard Business Review. August 2002. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ↑ Christensen, Clayton & Overdorf, Michael. (2000). "Meeting the Challenge of Disruptive Change"

- ↑ MIT Sloan Management Review Spring 2002. "How to identify and build New Businesses"

- ↑ Anthony, Scott D.; Johnson, Mark W.; Sinfield, Joseph V.; Altman, Elizabeth J. (2008). Innovator’s Guide to Growth. "Putting Disruptive Innovation to Work". Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 978-1-59139-846-2.

- ↑ Salge, T.O. & Vera, A. (2009). "Hospital innovativeness and organizational performance". Health Care Management Review. Vol. 34, Issue 1, pp. 54–67.

- ↑ Perez, T. and Rushing R. (2007). "The CitiStat Model: How Data-Driven Government Can Increase Efficiency and Effectiveness". Center for American Progress Report. pp. 1–18.

- ↑ Transportation Research Board (2007). "Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Synthesis 70: Mobile Data Terminals". pp. 1–5. TCRP (PDF).

- ↑ Von Hippel, Eric (1988). The Sources of Innovation (PDF). Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ↑ Engelberger, J. F. (1982). "Robotics in practice: Future capabilities". Electronic Servicing & Technology magazine.

- ↑ Kline (1985). Research, Invention, Innovation and Production: Models and Reality, Report INN-1, March 1985, Mechanical Engineering Department, Stanford University.

- 1 2 3 Mark, M., Katz, B., Rahman, S., and Warren, D. (2008) MetroPolicy: Shaping A New Federal Partnership for a Metropolitan Nation. Brookings Institution: Metropolitan Policy Program Report. pp. 4–103.

- ↑ "New Trends in Innovation Management". Forbesindia.com. Forbes India Magazine. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "ShipIt Days". Atlassian. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "U-STIR". U-stir.eu. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ Tuomi, I. (2002). Networks of Innovation. Oxford University Press. Networks of Innovation

- ↑ Siltala, R. (2010). Innovativity and cooperative learning in business life and teaching. University of Turku.

- 1 2 Davila, T., Epstein, M. J., and Shelton, R. (2006). "Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It." Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing.

- ↑ Khan, A. M (1989). I"nnovative and Noninnovative Small Firms: Types and Characteristics". Management Science, Vol. 35, no. 5. pp. 597–606.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, David (2002). "Framework for Managing Development in the Networked Organisations". Journal of Computers in Industry 47(1): 77–88.

- ↑ Tarde, G. (1903). The laws of imitation (E. Clews Parsons, Trans.). New York: H. Holt & Co.

- ↑ Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of Innovation. New York, NY: Free Press.

- ↑ Davila, Tony; Marc J. Epstein and Robert Shelton (2006). Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It. Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing

- ↑ OECD The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities. Proposed Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Technological Innovation Data. Oslo Manual. 2nd edition, DSTI, OECD / European Commission Eurostat, Paris 31 December 1995.

- ↑ "Industrial innovation – Enterprise and Industry". Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ Chalkidou K, Tunis S, Lopert R, Rochaix L, Sawicki PT, Nasser M, Xerri B. "Comparative Effectiveness research and Evidence-Based Health Policy: Experience from Four Countries". The Milbank Quarterly 2009; 87(2): 339–67 at 362–63.

- ↑ Roughead E, Lopert R and Sansom L. "Prices for innovative pharmaceutical products that provide health gain: a comparison between Australia and the United States Value". Health 2007. 10:514–20

- ↑ Hughes B. Payers "Growing Influence on R&D Decision Making". Nature Reviews Drugs Discovery 2008. 7: 876–78.

- ↑ Faunce T, Bai J and Nguyen D. "Impact of the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement on Australian medicines regulation and prices". Journal of Generic Medicines 201.; 7(1): 18-29

- ↑ Faunce TA (2006). "Global intellectual property protection of 'innovative' pharmaceuticals: Challenges for bioethics and health law in B Bennett and G Tomossy" (PDF). Law.anu.edu.au. Globalization and Health Springer. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ↑ Faunce TA. "Reference pricing for pharmaceuticals: is the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement affecting Australia's Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme?". Medical Journal of Australia. 20 August 2007. 187(4):240–42.

- ↑ "The INSEAD Global Innovation Index (GII)". INSEAD.

- ↑ "Home page". Innovation Capacity Index. Retrieved February 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Tools". Statsamerica.org. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ "The INSEAD Innovation Efficiency Inndex". Technology Review. February 2016.

- ↑ Kerle, Ralph. "Model for Managing Intangibility of Organizational Creativity: Management Innovation Index". Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship: 1300–1307.

- ↑ "Innovation Index". NYCEDC.com.

- ↑ "Home page". statetechandscience.org. Retrieved February 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The World Competitiveness Scoreboard 2014" (PDF). IMD.org. 2014.

- ↑ "These Are the World's Most Innovative Economies". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- ↑ "Infografik: Schweiz bleibt globaler Innovationsführer". Statista Infografiken. Statista (In German). Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- 1 2 Huebner, J. (2005). "A possible declining trend for worldwide innovation". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 72 (8): 980–986. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2005.01.003.

- ↑ Adler, Robert (2 July 2005). "Entering a dark age of innovation". New Scientist. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Hayden, Thomas (7 July 2005). "Science: Wanna be an inventor? Don't bother". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ Smart, J. (2005). "Discussion of Huebner article". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 72 (8): 988–995. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2005.07.001.

- ↑ Huebner, Jonathan (2005). "Response by the Authors". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 72 (8): 995–1000. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2005.05.008.

- ↑ Strumsky, D.; Lobo, J.; Tainter, J. A. (2010). "Complexity and the productivity of innovation". Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 27 (5): 496. doi:10.1002/sres.1057.

- ↑ Gordon, Robert J. (2012). "Is U.S. Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds". National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w18315.

- ↑ "Jonathan Wong, Head of DFID's Innovation Hub | DFID bloggers". Dfid.blog.gov.uk. 2014-09-24. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Grand Challenge Partners Commit to Innovation with New Investments in Breakthrough Science - Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation". Gatesfoundation.org. 2014-10-07. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "Global Development Lab | U.S. Agency for International Development". Usaid.gov. 2015-08-05. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "International Development Innovation Network (IDIN) | D-Lab". D-lab.mit.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "Global Innovation Fund International development funding". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "Human Development Innovation Fund (HDIF)". Hdif-tz.org. 2015-08-14. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "USAID and DFID Announce Global Development Innovation Ventures to Invest in Breakthrough Solutions to World Poverty | U.S. Agency for International Development". Usaid.gov. 2013-06-06. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "U.S. Economic Development Administration : Fiscal Year 2010 Annual Report" (PDF). Eda.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "Science and Technology". MEXT. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ "BMBF " Ministry". Bmbf.de. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ "Home". Landgate.wa.gov.au. Landgate Innovation Program. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "Welcome to TNQ20". Tropicalinnovationawards.com. Retrieved 2016-03-14.