Islam in Sweden

Among muslim residents of Sweden, as of 2014, 110,000 are registered as member of, or regularly served by, a muslim faith community.[1] Out of the roughly 500,000 Swedish residents with roots in countries and areas dominated by Muslims, approximately one third practice Islam to some extent.[2][3] Others are Cultural Muslims, apostates or convertites to other religions. Other sources set the figure at around 6% (almost 600 000) of the total Swedish population.[4]

History

The first registered Muslim groups in Sweden were Finnish Tatars who emigrated from Finland and Estonia in the 1940s. Islam began to have a noticeable presence in Sweden with immigration from the Middle East beginning in the 1970s.

Most Muslims in Sweden are either immigrants or descendants of immigrants. The majority are from the Middle East, in particular Iraq and Iran. However, 5 out of 6 Iranians in Sweden consider themselves secular rather than Muslim and are in strong opposition to the Islamic Republic regime in their ancestral home. Most Iranians and Iraqis fled as refugees to Sweden during the Iran-Iraq war from 1980 to 1988. The second-largest Muslim group consists of immigrants or refugees from former Yugoslavia, most of them are Bosniaks, who number 12,000. There is also a sizeable community of Somalis, who numbered 40,165 in 2011.

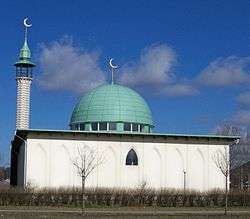

Sweden has a number of mosques providing the Muslim communities in Sweden places of worship.[5] The first mosque in Sweden was the Nasir Mosque, built in 1976. It was followed by the Malmö Mosque, 1984, and later, the Uppsala Mosque in 1995. More mosques were built during the 2000s, including the Stockholm Mosque (2000), the Umeå Mosque (2006) and the Fittja Mosque (completed 2007), among others. The governments of Saudi Arabia and Libya have financially supported the constructions of some of the largest Mosques in Sweden.[6][7]

As of the year 2000, an estimated 300,000 to 350,000 people of Muslim background lived in Sweden, or 3.5% of total population;[8] thereby included is anyone who fits the broad definition of someone who "belongs to a Muslim people by birth, has Muslim origin, has a name that belongs in the Muslim tradition, etc." regardless of personal religious convictions.[9]), of whom about 100,000 were second-generation immigrants (born in Sweden or immigrated as children).[10] In Sweden registration by personal belief is not common and is normally against the law, thus only figures of practising Muslims belonging to an Islamic community can be reported. In 2009, the Muslim Council of Sweden reported 106,327 registered members.[4]

In 2007 a documentary film, Aching Heart was released, documenting Muslim Swedes.[11]

Demography

Pew Research Center estimates the number of Muslims in Sweden at 451,000 (or 4.9% of the total population) for the year 2010. They project this to increase to 993,000 (or 9.9% of the total population) by the year 2030.[12] Although there are no official statistics of Muslims in Sweden, estimates count 200,000—250,000 people of Muslim background in 2000[8] (i.e. anyone who fits the broad definition of someone who "belongs to a Muslim people by birth, has Muslim origin, has a name that belongs in the Muslim tradition, etc. "[13]), roughly estimated close to 100,000 of which are second-generation.[10] Of the first-generation Muslims, 255,000 are thought to be Sunni, 5,000 Shi’ites, no more than 1,000 Ahmadiya, Alevi and other groups and probably no more than 5,000 converts – mainly women married to Muslim men.[14] In 2009 a US report stated that there are 450,000 to 500,000 Muslims in Sweden, around 5% of the total population, and that the Muslim Council of Sweden reported 106,327 officially registered members.[15] Swedish estimates are rather 350,000, including nominal Muslims and people from a Muslim background.

Such numbers do not imply religious beliefs or participation; Åke Sander claimed in 1992 that at most 40–50% of the people of Muslim background in Sweden "could reasonably be considered to be religious",[16] and in 2004, based on discussions and interviews with Muslim leaders, concerning second-generation Muslims born and raised in Sweden that "it does not seem that the percentage they consider to be religious Muslims in a more qualified sense exceeds fifteen percent, or perhaps even less".[17] Sander re-stated in 2004 that "we do not think it unreasonable to put the figure of religious Muslims in Sweden at the time of writing at close to 150,000".[18] Professor Mohammad Fazlhashemi at Umeå University estimates "a good 100,000".[19] About 25,000 are regarded as devout Muslims, visiting Friday prayers and practising daily prayers.

Muslims in Sweden most often originate from Iran, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Somalia, and Turkey. Muslim refugees from Syria, Iraq, Somalia, Eritrea, and Afghanistan are rapidly growing groups.

Conversion

There are no official statistics on the exact number of Swedish converts to Islam, but Anne Sofie Roald, a historian of religions at Malmö University College, estimates the number of converts from the Church of Sweden to Islam to be 3,500 people since the 1960s. Roald further states that conversions are also occurring from Islam to the Church of Sweden, most noticeably by Iranians, but also by Arabs and Pakistanis.[20]

The first known convert to Islam was the famous painter Ivan Aguéli who was initiated into the Shadhiliyya order in Egypt in 1909. It was Aguéli who introduced the French metaphysician René Guénon to Sufism. Aguéli is more known among Sufis by his Muslim name Abdul-Hadi al-Maghribi. Other well-known Swedish converts to Islam are Tage Lindbom, Kurt Almqvist, Mohammed Knut Bernström and Tord Olsson. Lindbom, Almqvist and Olsson are also initiates into various Sufi orders. Bernström translated the Quran into Swedish in 1998.

Places of worship

Several mosques have been built in Sweden since the 1980s, with notable ones in Malmö (1984) and Stockholm (2000). The Bellevue Mosque and the Brandbergen Mosque in the 2000s came to public attention as recruitment and propaganda centers for Islamist terrorism.[21][22]

The following are some of the places of Islamic worship that can be found today in Sweden.

| Name | Municipality | Year | Organization | Sect | Imam | Worship language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stockholm | ||||||

| Stockholm Mosque | Stockholm, Medborgarplatsen | 2000 | Islamiska Förbundet i Stockholm | Sunni | Abu Mahmoud | Arabic, Swedish |

| Bangladesh Jame Masjid | 23 Kocksgatan, Medborgarplatsen Stockholm | Sunni Hanafi | Bengali, Arabic | |||

| Fittja Mosque | Stockholm, Fittja | 2007 | Botkyrka Turkiska Islamiska Förening | Sunni (Hanafi) | Arabic, Turkish | |

| Brandbergen Mosque | Haninge (South Stockholm) | Haninge Islamiskt Kultur Center | Karim Laallam | Arabic | ||

| Imam Ali Mosque | Järfälla (West Stockholm) | Ahl Al Bayt Assembly | Shi'ite | Arabic, Persian | ||

| Central Sweden | ||||||

| Uppsala | Uppsala, Kvarngärdet | 1995 | Sunni | |||

| Örebro | Örebro, Vivalla | 2008 | ||||

| Southern Sweden | ||||||

| Bellevue Mosque | Gothenburg, Bellevue | Islamic Sunni Centre | Wahhabi | |||

| Musalla as-Salam | Gothenburg, Bellevue | Sunni (Shafi'i) | ||||

| Turkish Mosque 1 | Gothenburg, Hisingen | Sunni (Hanafi) | ||||

| skogås moske | skogås, stockholm | Sunni (unknown) | ||||

| Masjid Guraba | Gothenburg, Hisingen | Sunni | ||||

| Bosnian Mosque | Gothenburg, Hisingen | General | ||||

| Nasir Mosque | Gothenburg, Högsbo | 1976 | Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at | Ahmadiyya | Agha Yahya Khan | Arabic, Swedish, Urdu |

| Malmö Mosque | Malmö | 1984 | ||||

| Trollhättan Mosque | Trollhättan | 1985 | Shi'ite | |||

Associations

The beginning of national Islamic (Sunni) institutions in Sweden dates back to the creation of FIFS (Förenade Islamiska Församlingar i Sverige) in 1973–1974. In 1982 and 1984 two splits, due to internal rivalries, cultural differences, personal conflicts and funding, brought to the creation of SMF (Svenska Muslimska Förbundet) and ICUS, today IKUS (Islamska Kulturcenterunionen i Sverige). Others national institutions are BHIRF (Bosnien-Hercegovinas Islamiska riksförbund), founded in 1995 by Bosnian refugees, IRFS (Islamiska Riksförbundet), also since 1995, and SIA (Svenska Islamiska Akademin), founded in 2000 by the former ambassador Mohammed Knut Bernström, with the task of establishing in the future an Islamic university in Sweden, charged with imam education. SIA also publishes since February 2001 the periodical Minaret in Swedish.

On a lower level, specific Islamic organizations targeting specific groups have been created as well. SMUF, SUM (Sveriges Unga Muslimer), was the greatest youth Muslim organization since 1986, but after the inception of the Muslim Peacemovement (SMPJ) ("Swedish Muslims for Peace and Justice") that was founded in 2008 SMPJ has grown beyond that as the most active organization gathering young Muslims, students and professionals with local branches all over the country. SMPJ is today the fastest growing Muslim organization and already one of the largest peace movements in Sweden and a recognized NGO that has received several awards for its advocacy work, human rights work and contribution to Peace and Justice. SMPJ has kept outside the different internal rivalries of other Muslim organisations and gathers members from all of the different national Islamic institutions both Shia and Sunni (in accordance to the Amman message and is the only Muslim NGO that does that in Sweden today and is fully independent Muslim movement.

There exist also the women association IKF (Islamiska Kvinnoförbund i Sverige), the youth association IUF (Islamiska Ungdomförbundet i Sverige) and the imam association SIR (Sveriges Imamråd). IIF (Islamiska Informationföreningen) is a member association of FIFS aiming at providing information about Islam in Sweden; 1986–2000 it published Salaam, whose editorial board has always been dominated by women, mainly Swedish converts.

National and target organization have also created umbrella organizations in order to simplify their relationships to the state. FIFS and SMF have created in 1990 SMR (Sveriges Muslimska Råd), of which SUM is also member. The IKUS umbrella organization is named IRIS (Islamiska Rådet i Sverige) and includes also IKF, IUF and SIR. Above all, IS (Islamiska samarbetsrådet) deals with financial issues with the Commission for state grants to religious communities (SST); it includes FIFS, SMF, IKUS, ISS and SIF.

The following are some of the Islamic associations in Sweden:

- Islamic Association in Stockholm

- Muslim Association of Sweden (SMF)

- Muslim Council of Sweden (SMR)'

- Swedish Muslims for Peace and Justice (SMFR)

Controversies

Muslim Council of Sweden

Swedish social anthropologist Aje Carlbom and parliamentarian Abderisak Aden, who has founded the Islamic Democratic Institute (Islamiska demokratiska institutet), have both stated that they believe that at least part of the leading members of SMR support Islamist ideologies and are influenced by the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.[23]

The Muslim Council of Sweden (SMR), an umbrella organization for Swedish Muslim organizations, has been involved in several controversies. In 2006 Mahmoud Aldebe, one of the Board members of SMR, sent letters to each of the major political parties in Sweden demanding special legislation for Muslims in Sweden, including the right to specific Islamic holidays, special public financing for the building of Mosques, that all divorces between Muslim couples be approved by an Imam, and that Imams should be allowed to teach Islam to Muslim children in public schools. The request was condemned by all political parties and the government and the Swedish Liberal Party requested that an investigation be started by the Office of the Exchequer into the use of public funding of SMR. The Chairman of the Board of SMR subsequently stated that it supported the demands made by Aldebe but that it did not think that the letter had been a good idea to communicate them in a list of demands.[24]

Although the Board of SMR did not condemn Aldebe the letter has caused conflict within the organization.[25] SMR has also been accused of being closely allied to the Swedish Social Democratic Party, which has been criticised both inside and outside the party.[23]

Brandbergen Mosque

The Brandbergen Mosque has been described by the FBI terrorism consultant Evan Kohlmann as a propaganda central for the Armed Islamic Group (GIA). According to Kohlmann, people connected to the mosque also participated in the financing of GIA's bombing campaign in France in 1995.[21]

In 2004 an Arabic-language manual, which carried the logo and address of the Brandbergen Mosque, was spread on the internet. The manual described the construction of simple chemical weapons, including how to build a chemical munition from an ordinary artillery round.[26] On December 7, 2006, the Swedish citizen Mohamed Moumou, who is described by the United States Department of the Treasury as an "uncontested leader of an extremist group centered around the Brandbergen Mosque in Stockholm", was put on the United Nations Security Council Committee 1267 list of foreign terrorists.[27]

Investigative journalism uncovers discrimination against women

In 2012, the SVT program Uppdrag granskning visited 10 mosques once with a hidden camera and once with a visible camera. When the representatives were aware of being filmed, they stated that they supported values such as gender equality. However, when two undercover journalists posed as Muslim women with difficulties in their marriage, the answers from the majority of the visited imams were different. The imams told the women that they were expected to sleep with their husbands even if they did not want to, that they were to accept being beaten and strongly discouraged them to go to the police. Since about half of the visited mosques receive state or local funding, they are expected to promote basic values of Swedish society, such as equal rights between genders and to counteract discrimination and violence.[28]

Radical preachers invited to Sweden

In March 2014 Malmö Municipality withdrew financial support to a local association because they invited a Syrian lecturer who says that homosexuality should be punished by death to a charity event.[29] The organisers said that the lecturer would not attend and hold no speeches, but after a video recording showed him holding a lecture, the sum of money was recalled.[30]

In January 2015, Sigtuna council stopped radical Islamic preacher Haitham al-Haddad from holding a lecture at their premises.[31] He had been invited by Märsta Unga Muslimer (tr: Muslim Youth of Märsta) but when the council was informed of the preacher's homophobic and antisemitic views, the council cancelled the rental contract.[31]

According to cricism by British think-tank Quilliam in May 2015, Sweden is more likely than other countries to allow preachers with radical views to enter the country and spread their views.[32]

In May 2015, radical preacher Said Rageahs was invited to the mosque in Gävle where he promoted the views that whomever insults Mohammed should be killed along with apostates and advocated segregation between Muslims and non-Muslims.[33] The local imams at Gävle mosque ran the webpage muslim.se which espoused similar views (with the death penalty for homosexuality added) and according to islamologist Jan Hjärpe at Lund University their views are typical of wahhabists.[34]

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.sst.a.se/statistik/statistik2014.4.1295346115121ad63f315d2a.html

- ↑ Swedish religion, revised 2016- (in swedish)

- ↑ http://www.sst.a.se/statistik/statistik2014.4.1295346115121ad63f315d2a.html

- 1 2 International Religious Freedom Report 2014 : Sweden, U.S. Department Of State.

- ↑ David Westerlund, Ingvar Svanberg, Islam outside the Arab world, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, ISBN 978-0-312-22691-6, p. 392

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2 Sander (2004), pp. 218–224

- ↑ Sander (1990), pp. 16–17

- 1 2 Sander (2004), p. 224

- ↑ http://laikafilm.lcsthlm.com/detsviderihjartat/

- ↑ "The Future of the Global Muslim Population • Region: Europe". Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ Sander (1990), iversity, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Sander (2004), pp. 223–4

- ↑ "Sweden", International Religious Freedom Report 2009

- ↑ Sander (2004), p. 217

- ↑ Sander (2004), pp. 216–7

- ↑ Sander (2004), p. 218

- ↑ Prof. Mohammad Fazlhashemi about adjustment to Swedish law

- ↑ Svenska Dagbladet (SvD), Fler kristna väljer att bli muslimer, November 19, 2007 (Accessed November 19, 2007)

- 1 2 Petersson, Claes (July 13, 2005). "Terrorbas i Sverige" (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. Retrieved Mar 3, 2007.

- ↑ Lisinski, Stefan (11 November 2005). "Säpo utreder medhjälp till terrorbrott" (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ↑ Sveriges muslimska råd i krismöte Swedish Radio, Friday 28 April 2006 (in Swedish). A copy of the letter sent by Aldebe can be found here (in Swedish)

- ↑ Sydsvenska dagbladet, Krav på muslimska lagar i Sverige skapar maktkamp, 28 April 2006. Folkbladet i Norrköping, Imam: Vi vill ha egna lagar – men muslimska rådets krav möter hårt motstånd, 29 April 2006

- ↑ Evan Kohlmann (2004-09-18) Global terror alert. globalterroralert.com

- ↑ "Treasury Designations Target Terrorist Facilitators" (Press release). United States Department of the Treasury. Dec 7, 2006.

- ↑ Yllner, Nadja (16 May 2012). "Undercover report: Muslim leaders urges women to total submission". SVT – Uppdrag Granskning. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "Bidrag dras in efter homofobi-tal". Helsingborgs Dagblad. Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå. 20 Mar 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ "Utbetalning stoppas efter kritiserat besök". Sydsvenskan. 21 Mar 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- 1 2 ""Hatpredikant" inbjuden att tala i Sigtuna – stoppas av kommunen". Sveriges Television. 29 Jan 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ Scherman, Lena; Bernardson, Pia (7 May 2015). ""Sverige för flat mot hatpredikanter" (sv: Sweden too lenient towards hate preachers)". Sveriges Television. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ "Radikal imam fick predika i Gävles moské". Gefle Dagblad. 2015-06-21. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ↑ "Gävleimamen ansvarig för radikal hemsida". www.gd.se. Gefle Dagblad. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

Bibliography

- Sander, Åke (1990), Islam and Muslims in Sweden, Göteborg : Centre for the Study of Cultural Contact and International Migration, Gothenburg University

- Sander, Åke (2004), "Muslims in Sweden", by Muhammad Anwar, Jochen Blaschke and Åke Sander, State Policies Towards Muslim Minorities: Sweden, Great Britain and Germany, Berlin : Parabolis

Further reading

- Alwall, Jonas (1998), Muslim rights and plights : the religious liberty situation of a minority in Sweden, Lund : Lund University Press, pp. 145–238

- Carlbom, Aje (2006). "An Empty Signifier: The Blue-and-Yellow Islam of Sweden". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 26 (2): 245–261. doi:10.1080/13602000600937754.

- Carlbom, Aje (2003), The Imagined versus the Real Other : Multiculturalism and the Representation of Muslims in Sweden, Lund: Lund Monographs in Social Anthropology, pp. 63–163

- Nielsen, Jørgen S. (1992), Muslims in Western Europe, Edinburgh : Edinburgh University Press, pp. 80–84

- Sander, Åke (1993), Islam and Muslims in Sweden and Norway : a partially annotated bibliography 1980–1992 with short presentations of research centres and research projects, Göteborg : Centre for the Study of Cultural Contact and International Migration, Gothenburg University

- Sander, Åke (1997), “To what extent is the Swedish Muslim religious?”, in Steven Vertovec and Ceri Peach (eds.), Islam in Europe : The politics of religion and community, London : Macmillan and New York : St.Martin’s, pp. 179–210

.jpg)