Italian Egyptians

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,374 (2007) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Alexandria, Cairo, Suez, Port Said | |

| Languages | |

| Italian, Arabic, French | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Maltese in Egypt, Greeks in Egypt |

Italians in Egypt, also referred to as Italian Egyptians, are a community with a history that goes back to Roman times. Perhaps the most famous Italian Egyptian is Yolanda Christina Gigliotti, Dalida. Diva, famous singer and actress.

History

The last Queen of ancient Egypt (Cleopatra) married the Roman Mark Antony bringing her country as "dowry", and since then Egypt was part of the Roman Empire for seven centuries. Many people from the Italian peninsula moved to live in Egypt during those centuries: the tombs of Christian Alexandria shows how deep was that presence.[1]

Since then there has been a continuous presence of people (born in the Italian peninsula) and their descendants in Egypt.

Origins of actual community

During the Middle Ages Italian communities from the "Maritime Republics" of Italy (mainly Pisa, Genova and Amalfi) were present in Egypt as merchants. Since the Renaissance the Republic of Venice has always been present in the history and commerce of Egypt: there was even a Venetian Quarter in Cairo.

From the time of Napoleon I, the Italian community in Alexandria and Egypt started to grow in a huge way: the size of the community had reached around 55,000 just before World War II, forming the second largest expatriate community in Egypt.

World War II

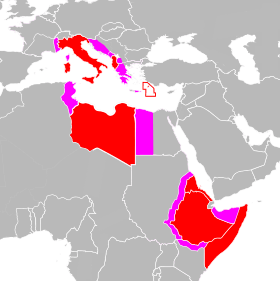

The expansion of the colonial Italian Empire after World War I was directed toward Egypt by Benito Mussolini, in order to control the Suez Canal.[2]

The Italian "Duce" created in the 1930s some sections of the National Fascist Party in Alexandria and Cairo, and many hundreds of Italian Egyptians become members of it. Even some intellectuals, like Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (founder of the Futurism) and the poet Giuseppe Ungaretti, were supporters of the Italian nationalism in their native Alexandria.

As a consequence, during World War II the British authorities interned in concentration camps nearly 8,000 Italian Egyptians with sympathy for Italian fascism, in order to prevent sabotage when the Italian Army attacked western Egypt in summer 1940.[3]

The areas of Egypt temporarily conquered by the Kingdom of Italy in the war (like Sallum and Sidi Barrani) were administered by the military.

Indeed, the nationalist organization Misr Al-Fatah (Young Egypt) was deeply influenced by the fascism ideals against the British Empire. The Young Egypt Party was ready to do a revolt in Cairo in summer 1942 if Rommel had conquered Alexandria after a victory at the El Alamein battle.[4]

However, like many other foreign communities in Egypt, migration back to Italy and the West reduced the size of the community greatly due to wartime internment and the rise of Nasserist nationalism against Westerners. After the war many members of the Italian community related to the defeated Italian expansion in Egypt were forced to move away, starting a process of reduction and disappearance of the Italian Egyptians.

After 1952 the Italian Egyptians were reduced - from the nearly 60,000 of 1940 - to just a few thousands. Most Italian Egyptians returned to Italy during the 1950s and 1960s, although a few Italians continue to live in Alexandria and Cairo. Officially the Italians in Egypt at the end of 2007 were 3,374 (1,980 families).[5]

In 2007 there were nearly 4,000 Italians in Egypt, mostly technicians and managers working (for a few years) in the 500 Italian companies with contracts with the Egyptian government: just a few hundreds of retired "real" Italian Egyptians remain, mainly in Alexandria and Cairo.

Egyptian–Italian relations

Italy's preeminence in its economic relations with Egypt was reflected in the size of its expatriate community. Some of the first educational missions that Egypt sent to Europe under Mohamed Ali were headed to Italy to learn the art of printing.

Mohamed Ali also engaged a number of Italian experts to assist in the various tasks of building the modern state: in the exploration of antiquities, the exploration of minerals, in the conquest of Sudan, designing the city of Khartoum and drawing the first survey map of the Nile Delta.

In addition, Italians featured prominently in the royal court under Ismail, which is perhaps why Italian architects were chosen to design most of Khedive Ismail's palaces, new suburbs of the capital and public buildings.

The most famous building related to the Italian community was the Royal Opera House, which was to be inaugurated in 1871 with the Aida by the Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi. The Khedivial Opera House or "Cairo Royal Opera House" was the original Opera House in Cairo. It was inaugurated on November 1869 and burned down on October 1971. The opera house was built on the orders of the Khedive Ismail to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal. The Italian Egyptian architects Pietro Avoscani and Mario Rossi designed the building.[6] Pietro Avoscani, before his 1891 death in Alexandria, created even the famous Corniche of Alexandria.[7]

The fondness of Egyptian monarchs towards Italy appeared in the number of Italians employed in their courts.

Italian-Egyptian relations were so strong and deemed so important that when the King of Italy Victor Emmanuel III abdicated in 1946 after Italy's defeat in World War II, Egyptian King Faruk invited Victor Emmanuel III to live in Alexandria. Victor Emmanuel III died in Alexandria in December 1947 and was buried there, behind the altar of St Catherine's Cathedral.

Areas of origin and residence

Before 1952, Italians formed the second largest expatriate community in Egypt, after the Greeks. The 1882 census of Egypt recorded 18,665 Italians in the country. By 1897 the figure rose to 24,454 and 30 years later to 52,462. Thus, the Italian community increased by 122 per cent in those years.

Writing in Al-Ahram of 19 February 1933, under the headline, "The Italians in Egypt", the Italian historian Angelo San Marco wrote, "The Venetians and the people from Trieste, Dalmatia, Genoa, Pisa, Livorno, Naples and Sicily continued to reside in Egypt long after their native cities fell into decay and lost their status as maritime centres with the decline of the Mediterranean as a major thoroughfare for world trade."

Elsewhere in the article, San Marco writes that the Italian community in Egypt held monopolies on the goods that were still popular in the East, which included many imports. The majority of the Italian community lived in either Cairo or Alexandria, with 18,575 in the former and 24,280 in the latter, according to the 1928 census.[8]

Italians tended to live in exclusively Italian neighbourhoods or in neighbourhoods with other foreigners. Perhaps the most famous of these districts in Cairo was known as the "Venetian Quarter". Nevertheless, San Marco notes that, in order to avoid harassment, the Italians tended to wear Egyptian dress and follow, as much as possible, Egyptian customs.

Community organisations

The Italian community in Egypt consisted primarily of a large array of merchants, artisans, professionals and an increasing number of workers. This was because Italy had remained for a long period of time politically and economically weak, which rendered it incapable of competing with the major industries and capitalist investment coming to Egypt from France.

During the fascist period there were eight public and six Italian parochial schools. The government schools were supervised by an official committee chaired by the Italian consul and they had a total student enrollment of approximately 1,500. Other schools had student bodies numbering in the hundreds. Italians in Alexandria also had 22 philanthropic societies, among which were the "National Opera Society", the "Society for Disabled War Veterans", the "Society of Collectors of Military Insignia", the "Italian Club", the "Italian Federation for Labour Cooperation", the "War Orphans Relief Society", the "Mussolini Italian Hospital" and the "Dante Alighieri Italian Language Association". In addition, many Italian-language newspapers were published in Alexandria, the most famous of which was L'Oriente and Il Messaggero Egiziano.[9]

Indeed, the hundreds of Italian words that have been incorporated into the Egyptian dialect is perhaps the best testimony to the fact that of all the foreign communities residing in Egypt, Italians were the most closely connected to Egyptian society.

San Marco ventures that the reason for this was that "our people are noted for their spirit of tolerance, their lack of religious or nationalist chauvinism and, unlike other peoples, their aversion to appearing superior."

Language and religion

All remaining Italian Egyptians speak Italian, while speaking Arabic and English as second language, and are Catholics.

The Italian Egyptians of the new generations are assimilated to the Egyptian society, and most of them speak mainly Arabic but still secondarily Italian (and sometimes English). In religion, most Italian Egyptians are Roman Catholics.

Notable people

- Anna Magnani, actress

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, poet and writer (founder of Futurism).

- Giuseppe Ungaretti, poet and essayist.

- Goffredo Alessandrini, script writer and film director.

- Angelo San Marco, historian

- Pietro Avoscani, architect.

- Yolanda Christina Gigliotti, better known as Dalida, famous singer and actress.

- Stephan Rosti, actor and film director.

- Rushdi Abaza, actor mother was Italian

- Stephan El Shaarawy, young football player born and raised in Italy who plays for AS Roma, his father is Egyptian and his mother is Italian.

- Antonio Lasciac, architect, engineer, poet and musician.

- Ashraf Saber, athlete born to an Egyptian father and an Italian mother.

- Adel Smith, founder of the Union of Italian Muslims. He was born in Naples to a Scottish father and an Egyptian mother

- Nadia Gamal, actress that was born in Alexandria as Maria Kardiadis to a Greek father and an Italian mother

- Lara Scandar, singer born in the USA to an Egyptian-Italian father and a Lebanese mother

See also

Notes

- ↑ Roman Catacombs in Alexandria

- ↑ Davide Rodogno. Fascism's European Empire p.243

- ↑ Internment of the Italian Egyptians (in Italian)

- ↑ Nasser and Sadat, 1942 revolt (in Italian)

- ↑ Official statistics on Italian Emigration

- ↑ History and photos of the Khedivial Opera House

- ↑ Photo of the Alexandria Corniche

- ↑ Marta Petricioli. L'Egitto degli italiani (1917-1947). Milano, Bruno Mondadori, 2007

- ↑ Lamb, Richard. Mussolini as Diplomat. Fromm International Ed. London, 1999 ISBN 0-88064-244-0

Bibliography

- Petricioli, Marta. Oltre il mito. L'Egitto degli Italiani (1917–1947) Mondadori. Milano, 2007 ISBN 978-88-424-2120-7

- Rodogno, Davide. Fascism's European Empire. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, 2006. ISBN 0-521-84515-7

- Serra, Luigi. L'Italia e l'Egitto dalla rivolta di Arabi Pascià all'avvento del fascismo. Marzorati Editore. Milano, 1991.

- Yannakakis, I. Alexandria 1860-1960. The brief life of a cosmopolitan community. Alexandria Press. Alexandria, 1997.

External links

- Close to Italy

- Website of the ANPIE, the Italian Egyptians organization (in Italian).

- History of the Italian emigration in Egypt

- 2008 Bibliotheca Alexandrina exposition Alexandria: An Italian Itinerary

- Gallery showing some photos of Italian influence in Alexandria