Italian occupation of Corsica

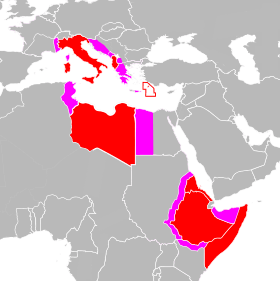

Italian-occupied Corsica refers to the military (and administrative) occupation by the Kingdom of Italy of the island of Corsica during World War II. It lasted from November 1942 to September 1943.[1]

History

After an initial period of increasing control over Corsica, Italian forces started losing territorial control to the local Resistance, and in the aftermath of the Italian capitulation to the Allies various units took different sides in the battle between newly landed German troops on one hand, and resistance fighters and Free French Forces on the other.

Occupation

On 8 November 1942, the Allies landed in North Africa. In response, Nazi Germany formulated Operation Anton, as part of which Italy occupied the island of Corsica on November 11 (Italian operation codename: "Operazione C2"), and some parts of France up to the Rhone.

The Italian occupation of Corsica had been strongly promoted by the Italian irredentist movement during Italy's Fascist period. The occupation force initially included 30,000 Italian troops and gradually reached the size of nearly 85,000 soldiers. This was a huge occupation force relative to the size of the local population of 220,000.[2]

The VII Army Corps of the Regio Esercito was able to occupy Corsica, which was still under the formal sovereignty of Vichy France, without a fight. Because of the initial lack of perceived partisan resistance and to avoid problems with Marshal Philippe Pétain, no Corsican units were formed under Italian control (except for a labour battalion in March 1943). The Corsican population initially showed some support for the Italians, partly as a consequence of irredentist propaganda.

The Italian troops grew to encompass two Army Divisions (the "Friuli" and the "Cremona"), two coastal Divisions (the Italian 225 Coastal Division and the Italian 226 Coastal Division), eight battalions of Fascist Militia, and some units of Military Police and Carabinieri.

The Italian troops were commanded by General Mondino until the end of December 1942, then by General Carboni until March 1943 and later by General Magli until September 1943.

Collaboration

In Corsica, the native collaborationists linked to the Italian irredentist movement supported the Italian occupation, stressing that this was a precautionary measure against a possible Anglo-American attack. Also some Corsican military officers collaborated with Italy, including the retired Major Pantalacci (and his son Antonio), Colonel Mondielli and Colonel Simon Petru Cristofini (and his wife, the first Corsican female journalist Marta Renucci).[3] Cristofini, who even met Benito Mussolini in Rome, was a strong supporter of the union of Corsica with Italy and defended irredentist ideals. Indeed, Cristofini actively collaborated with the Italian forces in Corsica during the first months of 1943 and (as head of the Ajaccio troops) helped the Italian Army to repress the Resistance in Corsica before the Italian Armistice in September 1943. He closely worked with the famous Corsican writer Petru Giovacchini, who was named as the potential "Governor of Corsica" had the Kingdom of Italy annexed the island.

In the first months of 1943 these irredentists, under the leadership of Petru Giovacchini and Bertino Poli, conducted large-scale propaganda efforts among the Corsican population to promote the unification of Corsica to Italy, as had been done in 1941 with Dalmatia (where Mussolini created the Governatorate of Dalmatia). Indeed, there was a mild support of the Italian occupation from most of the Corsican population until summer 1943.

The Italian occupation of Corsica was related to the Nazi Germany dominion of Europe over which Adolf Hitler ultimately exercised control: Benito Mussolini thus postponed the unification of Corsica to Italy until a "Peace Treaty" could be done after the hypothetical Axis victory in World War II, mainly because of German opposition to the irredentist claims.[4]

Administration

Social and economic life in Corsica was administered by the original French civil authorities, i.e. the préfet and four sous-préfets in Ajaccio, Bastia, Sartene and Corte.[5] On 14 November 1943, the préfet restated French sovereignty over the island and stated that the Italian troops were occupiers.

Rise of the Resistance

The French Resistance was initially limited, but it started taking shape immediately in the aftermath of the Italian invasion. This initially led to the development of two movements:[6]

- A network operating under the codename mission secrète Pearl Harbour (secret mission Pearl Harbor), which arrived from Algiers on 14 December 1942 aboard the Free French submarine Casabianca, the elusive "Phantom Submarine". Under the chief of the mission Roger de Saule, they coordinated various groups that merged in the Front national. Communists were most influential in this movement.

- The R2 Corse network was originally formed in connection with the London-based forces immediately under General de Gaulle in January 1943. Its leader Fred Scamaroni failed to unite the movements and was subsequently captured and tortured, committing suicide on 19 March 1943.

In April 1943 Paulin Colonna d'Istria was sent by Charles de Gaulle from Algeria and united the movements.

By early 1943, the Resistance was organized enough that it requested arms deliveries. The Resistance leadership was reinforced and the movement's morale was boosted by six visits by Casabianca carrying personnel and arms, and it was later further armed by Allied airdrops. This allowed the Resistance to increase its activities and establish greater territorial control, especially over the countryside in summer 1943.[6] In June and July 1943 the OVRA (Italian fascist police) and the fascist Black Shirts paramilitary groups started a large-scale repression. According to General Fernand Gambiez, 860 Corsicans were jailed and deported to Italy.[7] On 30 August, Jean Nicoli and two French partisans of the Front national were shot in Bastia by order of an Italian Fascist War Tribunal.

Liberation of Corsica (Operation Vesuvius)

Following the imprisonment of Benito Mussolini in July 1943, 12,000 German troops came to Corsica. They formally took over the occupation on 9 September 1943, the day after the armistice between Italy and the Allies. While their leaders were ambivalent, most of the Italian troops remained loyal to the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III and some fought (mainly at Teghime, Bastia and Casamozza[8]) alongside the French Resistance against the Nazi troops until the liberation of Corsica on 4 October 1943. Meanwhile, the French resistance aimed to establish control of the mountains in the island's center, with the goal of preventing the occupying forces from moving from one coast to the other and thus facilitating an Allied invasion.

The liberation of Corsica began with an uprising ordered by the local Resistance on 9 September 1943. The Allies did not initially want such a movement, preferring to focus their forces on the invasion of Italy. However, in light of the insurrection, the Allies acquiesced to the landing of elements of the reconstituted French I Corps on Corsica in September 1943, starting with one division of elite French troops being landed -- again -- via the submarine Casabianca at Arone near the village of Piana in the northwest of Corsica. This prompted the German troops to attack Italian troops as well as French resistants in Corsica. The Corsican and French Partisans and the Italian 44 Infantry Division Cremona, 20 Infantry Division Friuli engaged in heavy combat with the German Sturmbrigade Reichsführer SS and 90th Panzergrenadier Division, supported by the Italian 12th Parachute Battalion of the 184th Parachute Regiment),[9] which came from Sardinia and retreated through Corsica from Bonifacio towards the northern harbor of Bastia. On 13 September elements of the Free French 4th Moroccan Mountain Division were landed in Ajaccio to support the efforts to stop the 30,000 retreating German troops. During the night of 3 to 4 October the last German units evacuated Bastia and left for northern Italy, leaving behind 700 dead and 350 POWs.

Punishment of collaborators

After the war, nearly one hundred collaborators or autonomists (including intellectuals) were put on trial by the French authorities in 1946. Among those found guilty, eight were sentenced to death. However, only one irredentist was executed in the end: Petru Cristofini. He had been put on trial after the Allied liberation for treason and sentenced to death; he tried to kill himself, and was executed while he was dying in November 1943.[10]

Petru Giovacchini was forced to hide after the Free French and Allied invasion retaking the island. Prosecuted by a French tribunal in Corsica, he received a death sentence in 1945 and went into exile in Canterano, near Rome. He died on September 1955 as a consequence of former combat wounds, and since his death the Italian irredentist movement in Corsica is considered finished.

See also

- Italian irredentism in Corsica

- Italian occupation of France during World War II

- Petru Giovacchini

- Military history of Italy during World War II

- Royal Italian Army (1940–1946)

- History of Corsica

Notes

- ↑ Rodogno, Davide. Il nuovo ordine mediterraneo - Le politiche di occupazione dell'Italia fascista in Europa (1940-1943) Chapter: France

- ↑ Dillon, Paddy (2006). Gr20 - Corsica: The High-level Route. Cicerone Press Limited. p. 14. ISBN 1852844779.

- ↑ Vita e Tragedia dell'Irredentismo Corso, Rivista Storia Verità

- ↑ Marco Cuzzi: La rivendicazione fascista della Corsica (1938-1943) p. 57 (in Italian)

- ↑ Rodogno Davide: Italian occupation of Corsica p. 218

- 1 2 Hélène Chaubin, Sylvain Gregory, Antoine Poletti (2003). La résistance en Corse (CD-ROM). Paris: Association pour des Études sur la Résistance Intérieure.

- ↑ Général Gambiez. Liberation de la Corse. Hachette, Paris 1973, p. 128.

- ↑ "Regio Esercito - Divisione Friuli".

- ↑ "Esercito Italiano: Divisione "Nembo" (184)".

- ↑ Il Martirio di un irredento: il colonnello Petru Simone Cristofini. Rivista Storia Verità

References

- Jean-Marie-Arrighi et Olivier Jehasse. Histoire de la Corse et des Corses Colonna édition et Perrin. Paris, 2008

- Mastroserio, Giuseppe. Petru Giovacchini – Un Patriota esule in Patria. Editrice Proto. Bari, 2004.

- Rainero, R. Mussolini e Petain. Storia dei rapporti tra l'Italia e la Francia di Vichy. (10 giugno 1940-8 settembre 1943) Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito-Ufficio Storico, Roma, 1990

- Renucci, Janine. La Corse. Presses universitaires de France. Paris, 2001 ISBN 2130371698.

- Rodogno, Davide. Fascism's European empire: Italian occupation during the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, 2006 ISBN 0521845157

- Varley, Karine. 'Between Vichy France and Fascist Italy: Redefining Identity and the Enemy in Corsica during the Second World War', Journal of Contemporary History (2012) 47:3, 505-527 ISSN 0022-0094

- Vergé-Franceschi, Michel. Histoire de la Corse. Éditions du Félin. Paris, 1996 ISBN 2866452216.

- Vignoli, Giulio. Gli Italiani Dimenticati Ed. Giuffè. Roma, 2000

- Vita e Tragedia dell'Irredentismo Corso, Rivista Storia Verità, n.4, 1997

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Corsica in World War II. |