Italian Somalis

|

Postcard of Downtown Mogadishu in 1936. At the centre is the Catholic Cathedral, similar to that of Cefalù in Sicily and now destroyed. Near the Cathedral, the Arch monument is to commemorate King Umberto I of Italy. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (50,000 (Italian Somaliland, 1940[1][2] 5% of the population)) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Mogadishu | |

| Languages | |

| Italian, Somali, Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Italians, Somalis, Arabs, Italian Eritreans |

Italian Somalis (Italian: Italo-Somali) are Somali descendants from Italian colonists, as well as long-term Italian residents in Somalia.

History

In 1892, the Italian explorer Luigi Robecchi Bricchetti for the first time labeled as Somalia the region in the Horn of Africa referred to as Benadir. The area was at the time under the joint control of the Somali Geledi Sultanate (who, also holding sway over the Shebelle region in the interior, was at the height of its power) and the Omani Sultan of Zanzibar.[3]

Italian Somaliland

In April 1905, the Italian government acquired control (from a private Italian company called SACI) of this coastal area around Mogadishu, and created the colony of Italian Somaliland.

From the outset, the Italians signed protectorate agreements with the local Somali authorities.[4] In doing this, the Kingdom of Italy was spared bloody rebellions like those launched by the Dervish leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (the so-called "Mad Mullah") over a period of twenty-one years against the British colonial authorities in northern Somalia, an area then referred to as British Somaliland.[5]

In 1908, the borders with Ethiopia in the upper river Shebelle River (Uebi-Scebeli in Italian) were defined, and after World War I, the area of Oltregiuba ("Beyond Juba") was ceded by Britain and annexed to Italian Somaliland.

The dawn of Fascism in the early 1920s heralded a change of strategy for Italy. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi on December 15, 1923, the then-ruling northeastern Somali Sultanes were soon to be forced within the boundaries of La Grande Somalia. Italy hitherto had access to these areas under various protection treaties, but not direct rule.[4] Under its new leadership, Italy mounted successive military campaigns against the Somali Sultanate of Hobyo and Majeerteen Sultanate, eventually defeating the Sultanates' troops and exiling the reigning Sultans. The colonial troops called dubats and the gendarmerie zaptié were extensively used by De Vecchi in this military campaign.

In the early 1930s, the new Italian governors, Guido Corni and Maurizio Rava, started a policy of assimilation of the local populace, enrolling many Somalis in the Italian colonial troops. Some thousands of Italian settlers also began moving to Mogadishu as well as agricultural areas around the capital, such as Jowhar (Villaggio duca degli Abruzzi).[6]

In 1928, the Italian authorities built the Mogadishu Cathedral (Cattedrale di Mogadiscio). It was constructed in a Norman Gothic style, based on the Cefalù Cathedral in Cefalù, Sicily.[7] Following its establishment, Crowned Prince Umberto II made his first publicized visit to Mogadishu.[8][9]

Crowned Prince Umberto I would make his second publicized visit to Italian Somaliland in October 1934.[8]

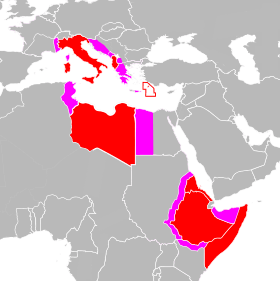

In 1936, Italy then integrated Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Italian Somaliland into a unitary colonial state called Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana), thereby enlarging Italian Somaliland from 500,000 km2 to 700,000 km2 with the addition of the Ogaden.

From 1936 to 1940, new roads such as the "Imperial Road" from Mogadishu to Addis Abeba were constructed in the region, as were new schools, hospitals, ports and bridges. New railways were also built, such as the famous Mogadishu-Villabruzzi Railway (Italian: Ferrovia Mogadiscio-Villabruzzi).

During the first half of 1940, there were about 22,000 to 50,000 Italians living in Italian Somaliland. In urban areas, the colony was one of the most developed on the continent in terms of standard of living.[1][10]

In the second half of 1940, Italian troops invaded British Somaliland[11] and ejected the British.[12] The Italians also occupied areas bordering Jubaland around the villages of Moyale and Buna.[13] However, Britain retained control of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited Northern Frontier District.[14][15][16]

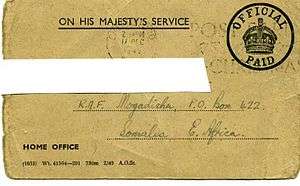

In the spring of 1941, Britain regained control of British Somaliland and conquered Italian Somaliland with the Ogaden.[12] However, until the summer of 1943, there was an Italian guerrilla war in all the areas of the former Italian East Africa.

After World War II

During the Second World War, Britain occupied Italian Somaliland and militarily administered the territory as well as British Somaliland. Faced with growing Italian political pressure inimical to continued British tenure and Somali aspirations for independence, the Somalis and the British came to see each other as allies. The first modern Somali political party, the Somali Youth Club (SYC), was subsequently established in Mogadishu in 1943; it was later renamed the Somali Youth League (SYL).[17]

In 1945, the Potsdam conference was held, where it was decided not to return Italian Somaliland to Italy.[12] and that the territory would be under British Military Administration (BMA). As a result of this failure on the part of the Big Four powers to agree on what to do with Italy's former colonies, Somali nationalist rebellion against the Italian colonial administration culminated in violent confrontation in 1948. 24 Somalis and 51 Italians died in the ensuing political riots in several coastal towns.[18]

In November 1949, the United Nations finally opted to grant Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland, but only under close supervision and on the condition—first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (later Hizbia Dastur Mustaqbal Somali, or HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL), that were then agitating for independence—that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.[19][20]

Despite the initial unrest, the 1950s were something of a golden age for the nearly 40,000 remaining Italian expatriates in Italian Somaliland. With United Nations funds pouring in and experienced Italian administrators who had come to see the territory as their home, infrastructural and educational development blossomed. Relations between the Italian settlers and the Somalis were also generally good.[21] This decade passed relatively without incident and was marked by positive growth in many sectors of local life.[22]

The economy was controlled by the Bank of Italy through emissions of the Somalo shilling, that was used as money in the Italian administered region from 1950 to 1962.

In 1960, Italian Somaliland declared its independence and united with British Somaliland in the creation of modern Somalia.[23]

In 1992, after the fall of the Siad Barre administration, Italian troops returned to Somalia to help restore peace during Operation Restore Hope (UNISOM I & II). Operating under a United Nations mandate, they patrolled for nearly two years the southern riverine area around the Shebelle River.[24][25]

By the early nineties, there were just a few dozen Italian colonists left. All were elderly and still concentrated in Mogadishu and its surroundings.[26] The last Italian colonist, Virginio Bresolin, died in Merka in early 2010.[27]

Italian population in Somalia

The first Italians moved to Somalia at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1923, there were fewer than a thousand Italians in Italian Somaliland.[28] However, it was not until after World War I that this number rose, with the settlers primarily concentrated in the towns of Mogadishu, Kismayo, Brava, and other cites in the south-central Benadir region.

The colonial period emigration to Italian Somaliland initially mainly consisted of men. Emigration of entire families was only later promoted during the Fascist period, mainly in the agricultural developments of the Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi (Jowhar), near the Shebelle River.[29] In 1920, the Societa Agricola Italo-Somala (SAIS) was founded by the Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi in order to explore the agricultural potential of central Italian Somaliland and create a colony for Italian farmers.[30]

The area of Janale in southern Somalia (near the Jubba River) was another place where Italian colonists from Turin developed a group of farms. Under governor De Vecchi, these agricultural areas cultivated cotton, and after 1931, also produced large quantities of banana exports.[31]

In 1935, there were over 50,000 Italians living in Italian Somaliland. Of those, 20,000 resided in Mogadishu (called Mogadiscio in Italian), representing around 40% of the city's 50,000 residents. Other Italian settler communities were concentrated in the Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi, Adale (Itala in Italian), Janale, Jamame, and Kismayo.[2][32][33] The same year, during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, there were more than 220,000 Italian soldiers stationed in Italian Somaliland.[34]

By March 1940, over 30,000 Italians lived in Mogadishu, representing around 33% of the city's total 90,000 residents.[32][35] They frequented local Italian schools that the colonial authorities had opened, such as the Liceum.[29]

Italian Somalis were concentrated in the cities of Mogadishu, Merca, Baidoa, Kismayo and the agricultural areas of the riverine Jubba and Shebelle valleys (around Jowhar/Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi).

After World War II, the number of Italians in Somali territory started to decrease. By 1960 and the establishment of the Somali Republic, their numbers had dwindled to less than 10,000. Most Italian settlers returned to Italy, while others settled in the United States, United Kingdom, Finland and Australia. In 1972, there were 1,575 Italians remaining in Somalia, down from 1,962 in 1970. This decline was largely due to the nationalization policy adopted by the Siad Barre administration.[36] By 1989, there were only 1,000 of the settlers left, with fewer after the start of the civil war and the fall of the Barre regime in 1991. Many Italian Somalis had by then departed for other countries. With the disappearance of Italians from Somalia, the number of Roman Catholic adherents dropped from a record high of 8,500 parishioners in 1950 (0.7% of Mogadishu's population) to just 100 individuals in 2004.[37]

| year | Italian Somalis | population | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | 1,000 | 365,300 | <1% | ||||

| 1930 | 22,000 | 1,021,000 | 2% | ||||

| 1940 | 30,000 | 1,150,000 | 3% | ||||

| 1945 | 50,000 | n/a | n/a | ||||

| 1960 | 10,000 | 2,230,000 | <1% | ||||

| 1970 | 1,962 | 3,601,000 | <1% | ||||

| 1972 | 1,575 | n/a | <1% | ||||

| 1989 | 1,000 | 6,089,000 | <1% | ||||

| 2015 | <1,000 | 10,63,000 | <1% | ||||

| The Italian Somali population in Somalia, from 1914 to 1989 | |||||||

Italian language in Somalia

Prior to the Somali civil war, the legacy of Italian influence in Somalia was evinced by the relatively wide use of the Italian language among the country's ruling elite. Until World War II, the Italian language was the only official language of Italian Somaliland. Italian was official in Italian Somaliland during the Fiduciary Mandate, and the first years of independence.

By 1952, the majority of Somalis had some understanding of the language.[38] In 1954, the Italian government established post-secondary institutions of law, economics and social studies in Mogadishu. These institutions were satellites of the University of Rome, which provided all the instruction material, faculty and administration. All the courses were presented in Italian. By the end of the trust period in 1960, over 200,000 people in the nascent Somali Republic spoke Italian.[39] In 1964, the institutions offered two years of study in Somalia, followed by two years of study in Italy. After a military coup in 1969, all foreign entities were nationalized, including Mogadishu's principal university, which was renamed Jaamacadda Ummadda Soomaliyeed (Somali National University).

Until 1967, all schools in central and southern Somalia taught Italian.[40] In 1972, the Somali language was officially declared the only national language of Somalia, though it now shares that distinction with Arabic. Due to its simplicity, the fact that it lent itself well to writing Somali since it could cope with all the sounds in the language, and the already widespread existence of machines and typewriters designed for its use,[41] the government of Somali president Mohamed Siad Barre, following the recommendation of the Somali Language Committee that was instituted shortly after independence with the purpose of finding a common orthography for the Somali language, unilaterally elected to only use the Latin script for writing Somali instead of the long-established Arabic script and the upstart Osmanya script.[42] During this period, Italian remained among the languages used in higher education.[43] In 1983, nine out of the twelve faculties in the Somali National University used Italian as the language of instruction.[44] Until 1991, there was also an Italian school in Mogadishu (with courses of Middle school and Liceum), later destroyed because of the civil war.[45]

The Somali language also contains a few Italian loanwords that were retained from the colonial period.[46] The most widely used is ciao, meaning goodbye.[40] As part of a broader governmental effort to ensure and safeguard the primacy of the Somali language, the post-independence period in Somalia saw a push toward replacement of such foreign loanwords with their Somali equivalents or neologisms. To this end, the Supreme Revolutionary Council during its tenure officially prohibited the borrowing and usage of Italian and English terms.[46]

Alongside English, Italian was declared a second language of Somalia by the Transitional Federal Government in the Transitional Federal Charter adopted in 2004. Somali (Maay and Maxaa-tiri) and Arabic were the official national languages.[47] Following the adoption of the Provisional Constitution in 2012 by the Federal Government of Somalia, Somali and Arabic were retained as sole official languages.[48]

Notable Italian Somalis

- Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, mountaineer and explorer; member of the royal House of Savoy.

- Annalena Tonelli, lawyer and social activist.

- Cristina Ali Farah, writer and poet.

- Jonis Bashir, actor and musician.

- Elisa Kadigia Bove, activist and voice and film actress.

- Saba Anglana, actress and international singer.[49]

- Luciano Ceri, singer-songwriter, journalist and radio host.

- Zahra Bani, athletic champion (javelin).

- Fabio Liverani, professional football player and coach.

- Salvatore Colombo, Bishop of Mogadishu.

- Leonella Sgorbati, Catholic nun.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Gallo, Adriano. Memories from Somalia". Hiiraan Online. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- 1 2 A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe and Its Empires. p. 311. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

- ↑ I. M. Lewis, A modern history of Somalia: nation and state in the Horn of Africa, (Westview Press: 1988), p.38

- 1 2 Mariam Arif Gassem, Somalia: clan vs. nation, (s.n.: 2002), p.4

- ↑ Laitin, David. Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience Section: Italian Influence. p. 73

- ↑ Bevilacqua, Piero. Storia dell'emigrazione italiana. p. 233

- ↑ Giovanni Tebaldi. Consolata Missionaries in the World (1901-2001). p. 127. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- 1 2 R. J. B. Bosworth. Mussolini's Italy: Life Under the Fascist Dictatorship, 1915-1945. p. 48. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ↑ Peter Bridges. Safirka: An American Envoy. p. 71. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ↑ Tripodi, Paolo. The Colonial Legacy in Somalia. p. 66

- ↑ Mussolini Unleashed, 1939-1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. p. 138. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- 1 2 3 Federal Research Division, Somalia: A Country Study, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p.38

- ↑ "The loss of Italian East Africa (in Italian)". La Seconda Guerra Mondiale. n.d. Archived from the original on 2 August 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Africa Watch Committee, Kenya: Taking Liberties, (Yale University Press: 1991), p.269

- ↑ Women's Rights Project, The Human Rights Watch Global Report on Women's Human Rights, (Yale University Press: 1995), p.121

- ↑ Francis Vallat, First report on succession of states in respect of treaties: International Law Commission twenty-sixth session 6 May-26 July 1974, (United Nations: 1974), p.20

- ↑ I. M. Lewis, A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p.304.

- ↑ Melvin Eugene Page, Penny M. Sonnenburg. "Colonialism: An International, Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia". p. 544. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Zolberg, Aristide R., et al., Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World, (Oxford University Press: 1992), p.106

- ↑ Gates, Henry Louis, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1749

- ↑ Ak̲h̲tar Ḥusain Rāʼepūrī. "The dust of the road: a translation of Gard-e-Raah". p. 200. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ "Italian life in Somaliland during the Fifties and Sixties". Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ↑ "BBC News: Somalia profile". 19 December 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Tripodi, Paolo. The Colonial Legacy in Somalia p. 88

- ↑ "UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN SOMALIA II UNOSOM II (March 1993 - March 1995)". Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Aidan Hartley. The Zanzibar Chest: A Story of Life, Love, and Death in Foreign Lands. p. 181. Retrieved 2014-04-05.

- ↑ "Somalia bears scars of a former colonial state". 2010-02-18. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

- ↑ Robert L. Hess. Italian colonialism in Somalia. p. 108. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

- 1 2 Gian Luca Podestà. "Italian emigration in East Africa (in Italian)" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- ↑ Tropical Africa's Emergence As a Banana Supplier in the Inter-War Period. p. 77. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ↑ "Somalia-THE COLONIAL ECONOMY". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- 1 2 Fernando Termentini. "Somalia, a nation that does not exist (In Italian)". Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- ↑ Rolando Scarano. "The Italian Rationalism in the colonies 1928 to 1943: The "new architecture" of Terre Overseas (In Italian)" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- ↑ Nicolle, David, "The Italian Invasion of Abyssinia 1935–1936", p. 41

- ↑ Ferdinando Quaranta di San Severino (barone). Development of Italian East Africa. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ Centro di documentazione. Italy; Documents and Notes, Volume 22. p. 357. Retrieved 2014-03-30.

- ↑ "Diocese of Mogadiscio". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ↑ United States. Hydrographic Office. Publications, Issue 61. p. 9.

- ↑ Statistical Report on the Languages of the World: Cumulative Index of the Language of the World. p. 74. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

- 1 2 David D. Laitin. Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. p. 67. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ↑ Andrew Simpson, Language and National Identity in Africa, (Oxford University Press: 2008), p.288

- ↑ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.73

- ↑ Mohamed Haji Mukhtar. Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 125. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ↑ Lee Cassanelli and Farah Sheikh Abdikadir. "Somalia: Education in Transition". p. 103. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ↑ "Photo of a mixed Italian and Somali school in Mogadishu". 11 October 2008. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- 1 2 Ammon, Ulrich; Hellinger, Marlis (1992). Status Change of Languages. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 128–131.

- ↑ According to article 7 of Transitional Federal Charter for the Somali Republic: The official languages of the Somali Republic shall be Somali (Maay and Maxaatiri) and Arabic. The second languages of the Transitional Federal Government shall be English and Italian.

- ↑ According to article 5 of Provisional Constitution: The official language of the Federal Republic of Somalia is Somali (Maay and Maxaa-tiri), and Arabic is the second language.

- ↑ "World, Music, Network: Saba Anglana". Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

Bibliography

- Antonicelli, Franco. Trent'anni di storia italiana 1915 - 1945. Mondadori Editore. Torino, 1961.

- Bevilacqua, Piero. Storia dell'emigrazione italiana. Donzelli Editore. Roma, 2002 ISBN 88-7989-655-5

- Hess, Robert L. Italian Colonialism in Somalia. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, 1966.

- Laitin, David. Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, 1977 ISBN 0-226-46791-0

- MacGregor, Knox. Mussolini unleashed 1939-1941. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, 1980.

- Mohamed Issa-Salwe,Abdisalam. The Collapse of the Somali State: The Impact of the Colonial Legacy. Haan Associates Publishers. London, 1996.

- Page, Melvin E. Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO Ed. Oxford, 2003 ISBN 1-57607-335-1

- Tripodi, Paolo. The Colonial Legacy in Somalia. St. Martin's Press. New York, 1999.

External links

- Interview with Italian Somalis in Italy: Part One (in Italian)

- Interview with Italian Somalis in Italy: Part Two (in Italian)

- Reunion of Italian Somalis in Italy (largely in Italian and Somali)

- Website of Italian Somalis in Italy (in Italian)

- Blog of Italian Somalis (in Italian)

- Article with photos on a 2005 visit to 'Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi' (Jowhar) and areas of former Italian Somalia (in italian)

- Website of the exiled Italians of Somalia, with photos of the colonial era (in italian)

- Photos of the destroyed Catholic Cathedral of Mogadiscio, similar to a Norman Cathedral in Sicily

- Detailed map of Somalia in 1936

.svg.png)