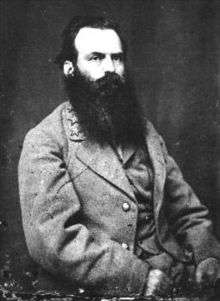

James L. Kemper

| James L. Kemper | |

|---|---|

| |

| 37th Governor of Virginia | |

|

In office January 1, 1874 – January 1, 1878 | |

| Lieutenant |

Robert E. Withers Henry Wirtz Thomas |

| Preceded by | Gilbert Carlton Walker |

| Succeeded by | Frederick W. M. Holliday |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates | |

|

In office 1853 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

June 11, 1823 Madison County, Virginia |

| Died |

April 7, 1895 (aged 71) Walnut Hills, Orange County, Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Cremora "Belle" Conway Cave |

| Alma mater | Washington College |

| Profession | Lawyer, Soldier, Politician |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service |

1846–1848 (USA) 1861–1865 (CSA) |

| Rank |

|

| Unit | Regiment of Virginia Volunteers (USA) |

| Commands |

7th Virginia Infantry Kemper's Brigade Kemper's Division Virginia Reserve Forces |

| Battles/wars | |

James Lawson Kemper (June 11, 1823 – April 7, 1895) was a lawyer, a Confederate general in the American Civil War, and the 37th Governor of Virginia. He was the youngest of the brigade commanders, and the only non-professional military officer, in the division that led Pickett's Charge, in which he was wounded and captured but rescued.

Early and family life

Kemper was born at Mountain Prospect plantation in Madison County, Virginia, the son of William and Maria E. Allison Kemper. His father's family had emigrated from near what became Siegen, Germany, in the early 18th century. His great-grandfather had been among the miners recruited for Governor Alexander Spotswood's colony at Germanna, Virginia,[1] and his merchant father had moved to the new town of Madison Court House in the 1790s after his own father had died falling from a horse in 1783, leaving his widow to take care of five daughters and a son. By the time young James was born, his paternal grandmother and four aunts also lived at the plantation which William Kemper had bought for $5,541.40 in 1800. His maternal great-grandfather, Col. John Jasper Stadler, had served on George Washington's staff as a civil engineer and planned fortifications in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina during the American Revolutionary War, and his grandfather John Stadler Allison served as an officer in the War of 1812, but died when his daughter Maria was very young.[2] Although several of his paternal ancestors were involved in the German Reformed Church, William Kemper was an elder in the local Presbyterian church and his mother was devout, but also hosted dances and parties that lasted several days. His brother, Frederick T. Kemper later founded Kemper Military School).

James Kemper had virtually no military training as a boy, but his father and a neighboring planter, Henry Hill of Culpepper, founded Old Field School on the plantation to educate local children, including A.P. Hill, who became a lifelong friend. From 1830-1840, Kemper boarded during winters at Locust Dale Academy, which had a military corps of cadets.[3] Kemper later attended Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) and also took civil engineering classes at nearby Virginia Military Institute. At Washington College's graduation ceremony in 1842, 19-year-old Kemper gave the commencement address, taking for a topic "The Need of a Public School System in Virginia." Kemper then returned home, where he joined a Tee-Total (Temperance) Society as well as studied law under George W. Summers of Kanawha County (a former U.S. Representative), after which Washington College awarded him a Master's degree in June 1845. He was admitted to the Virginia bar on October 2, 1846.[4]

Military and early political career

After Congress had declared war on Mexico in 1846, President James K. Polk called for nine regiments of volunteers. Kemper and his friend Birkett D. Fry of Kanawha County traveled to the national capital on December 15, 1846, hoping to secure commissions in the First Regiment of Virginia Volunteers. After traveling to Richmond and back to Washington for more networking, Kemper learned that he had been appointed the unit's quartermaster and captain under Col. John F. Hamtramck. During the Mexican-American War, Kemper received favorable reviews and met many future military leaders, but his unit arrived just after the Battle of Buena Vista and mainly maintained a defensive perimeter in Coahuila province.[5]

Honorably discharged from the U.S. Army on August 3, 1848, Kemper returned to practice law in Madison County, and neighboring Orange and Culpeper Counties. He represented many fellow veterans making land claims, as well as speculated in real estate and helped form the Blue Ridge Turnpike Company (between Gordonsville and the Shenandoah Valley.[6]

Interested in politics, Kemper first campaigned for office in 1850, but lost the contest to become clerk of the Commonwealth's constitutional convention. Promoting himself as pro-slavery, anti-abolitionist, and pro-states' rights, Kemper defeated Marcus Newman and was elected to represent Madison County in the Virginia House of Delegates in 1853 (the year his father died at age 76).[7] A strong advocate of state military preparedness, as well as an ally of Henry A. Wise, Kemper rose to become chairman of the Military Affairs Committee. By 1858 he was a brigadier general in the Virginia militia.

In early 1861 Kemper became Speaker, a position he held until January 1863. Much of his term as Speaker coincided with his service in the Confederate States Army.

Civil War

After the start of the Civil War, Kemper served as a brigadier general in the Provisional Army of Virginia, and then a colonel in the Confederate States Army, becoming head of the 7th Virginia Infantry. At First Bull Run, Kemper led the regiment as part of Jubal Early's brigade. His regiment was later assigned to Brig. Gen. A.P. Hill's brigade in Maj. Gen. James Longstreet's division of the Confederate Army of the Potomac from June 1861 to March 1862. On May 26, A.P. Hill was promoted to division command and Kemper got the brigade. After a gallant performance at the Battle of Seven Pines during the Peninsula Campaign, Kemper was promoted to brigadier general on June 3, 1862. Leading the brigade through the Seven Days Battles, he then became a division commander after Robert E. Lee reorganized the army (commanding half of James Longstreet's old division).

At the Second Battle of Bull Run, Kemper's division took part in Longstreet's surprise attack against the Union left flank, almost destroying Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia. Afterwards, his division was merged into General David R. Jones's command and Kemper reverted to brigade command. At the Battle of Antietam he was south of the town of Sharpsburg, defending against Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's assault in the afternoon of September 17, 1862. He withdrew his brigade in the face of the Union advance, exposing the Confederate right flank, and the line was saved only by the hasty arrival of A.P. Hill's division from Harpers Ferry.

When George Pickett returned to duty after Antietam, he took command of the troops Kemper had led at Second Bull Run. In 1863, the brigade was assigned to Pickett's Division in Longstreet's Corps, which meant that he was absent from the Battle of Chancellorsville, while the corps was assigned to Suffolk, Virginia. However, the corps returned to the army in time for the Gettysburg Campaign.

At the Battle of Gettysburg, Kemper arrived with Pickett's Division late on the second day of battle, July 2, 1863. His brigade was one of the main assault units in Pickett's Charge, advancing on the right flank of Pickett's line. After crossing the Emmitsburg Road, his brigade was hit by flanking fire from two Vermont regiments, driving it to the left and disrupting the cohesion of the assault. Kemper rose on his stirrups to urge his men forward, shouting "There are the guns, boys, go for them!"

This bravado made him a more visible target and he was wounded by a bullet in the abdomen and thigh and captured by Union troops. He was rescued by Sgt. Leigh Blanton of the 1st Virginia,[8] and was carried back to Confederate lines on Seminary Ridge. General Robert E. Lee encountered Kemper being carried on a stretcher and inquired about the seriousness of his wound, which Kemper said he thought was mortal. He requested that Lee "do full justice to this division for its work today."[9] During the Confederate Army's retreat from Gettysburg, Kemper was again captured by Union forces. He was exchanged (for Charles K. Graham) on September 19, 1863.[10] For the rest of the war he was too ill for combat, and commanded the Reserve Forces of Virginia. He was promoted to major general on September 19, 1864.

Postbellum career

Kemper was paroled in May, 1865. Since his previous house had been destroyed in a raid led by future Gen. George Armstrong Custer, his mother-in-law purchased a house for the family in Madison County. Kemper then resumed his legal career. However, the bullet that had wounded him at Gettysburg had lodged close to a major artery and could not be removed without risking his life, so he suffered groin pain for the rest of his life. Nonetheless, he tried to attract northern capital to rebuild the devastated local economy. He and former classmate and Confederate general John D. Imboden also maintained a general legal practice, which because of the times, included much bankruptcy law.

Beginning in 1867, Kemper helped found Virginia's Conservative Party, initially to oppose the new state constitution adopted by a convention chaired by John Underwood (who allied with the Radical Republican faction and opposed allowing former Confederates the vote, among other measures). In 1869 Kemper allied with another former Confederate general turned railroad entrepreneur William Mahone to elect Gilbert C. Walker to the Virginia House of Delegates.[11]

After his beloved 33-year old wife Bella[12] died in September 1870 of complications from the birth of their seventh child, Kemper's political activities increased. Distraught from the loss, he no longer slept in the house they had shared, but in his law office.[13] Kemper ran for Congress in the 7th Congressional District (after the redistricting caused by the 1870 census), but lost to incumbent John T. Harris of Harrisonburg.

In the 1873 election for Governor of Virginia, as the Reconstruction Era ended and former Confederate soldiers regained voting rights, Kemper handily defeated former Know-Nothing and fellow ex-Confederate turned Republican Robert William Hughes of Abingdon, who won only 43.84% of the votes cast. Kemper's supporters included former Confederate Generals Jubal Early and Fitzhugh Lee as well as Mahone and noted raider John Singleton Mosby. However, former Governor and Confederate General Henry A. Wise supported Hughes.

Kemper served as Virginia's Governor from January 1, 1874, to January 1, 1878. He lived frugally, using his son Meade (d. 1886) as his secretary. Kemper trimmed the state budget where possible, and late in his term advocated taxing alcohol. One major political controversy involved whether to repay the state's war debt. Kemper allied with the Funder Party to pay it off; the Readjuster Party (which Mahone came to lead) opposed him. Gov. Kemper also enforced the civil rights provisions in the new state constitution, despite having opposed it originally. His February 1874 veto of a new law passed by the General Assembly that attempted to transfer control in Petersburg from elected officials (including African Americans) to a board of commissioners appointed by a judge was sustained by Virginia's Senate, although the law's proponents hanged him in effigy. Gen. Early also vehemently disagreed with Kemper's 1875 decision to allow a militia unit of African Americans to participate in the dedication of a statue of Gen. Stonewall Jackson. Gov. Kemper also attempted prison reform and built public schools despite budget shortages. His last major public reception, in October 1877, hosted President Rutherford B. Hayes who opened the state fair in Richmond.[14] One modern historian analogized Kemper's Conservative philosophy (and that of other Virginia Redeemers) to that of Gov. Wade Hampton of South Carolina.[15]

Death and legacy

As his term of office ended (the state Constitution forbidding his re-election), Kemper (with his six surviving children and various domestic animals) returned to farming and his legal practice. He sold the Madison County home and purchased a house known as Walnut Hills, which overlooked the Rapidan River and Blue Ridge Mountains and was near the Orange County courthouse.[16] However, complications from the inoperable bullet worsened, and eventually paralyzed his left side. Kemper died on April 7, 1895 and was buried in the family cemetery.[17]

Virginia erected a historic marker at Kemper's former home,[18] which has now been restored by the Madison County Historical Society and other organizations, and is available for receptions and other activities.[19] It is part of the Madison Courthouse historic district.[20] His papers are held by the Library of Virginia.[21]

Because Kemper (like Mahone) supported education of African-Americans, some schools for African-Americans founded during his governorship were named after him, including Kemper School No. 4 in the Arlington District of Alexandria County, Virginia.[22][23]

Also, the Kemper Street Industrial Historic District in Lynchburg, Virginia straddles the former Lynchburg and Durham Railroad, construction of which began in May, 1887; the Norfolk and Southern Railroad acquired the line in 1898, which spurred that district's industrial growth.[24]

In popular media

Actor Royce D. Applegate portrayed Kemper in two films, Gettysburg (1993) and Gods and Generals (2003).

See also

Notes

- ↑ John W. Wayland, Germanna at page 13

- ↑ Harold R. Woodward, Jr., The Confederacy's Forgotten Son (Rockbridge Publishing Company, 1993) at pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Woodward at pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Woodward at pp. 6-8.

- ↑ Woodward at pp. 9-15.

- ↑ Woodward at pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Woodward at pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 61.

- ↑ Freeman, vol. 3, p. 130.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 330.

- ↑ http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/kemper_james_lawson_1823-1895#start_entry

- ↑ http://civilwarwomenblog.com/cremora-belle-cave-kemper/

- ↑ http://civilwarwomenblog.com/cremora-belle-cave-kemper/

- ↑ http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/kemper_james_lawson_1823-1895#start_entry

- ↑ Robert R. Jones, "James L. Kemper and the Virginia Redeemers Face the Race Question: A Reconsideration." Journal of Southern History 1972 38(3): 393–414.

- ↑ http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/kemper_james_lawson_1823-1895#start_entry

- ↑ http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=11006

- ↑ http://www.markerhistory.com/james-l-kemper-residence-marker-je-3/

- ↑ http://www.madisonvahistoricalsociety.org/Facilities.html

- ↑ NRIS continuation page 5, item 7, available at http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Counties/Madison/256-0004_%20Madison_County_Courthouse_Historic_District_1984_Final_Nomination.pdf

- ↑ http://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=lva/vi00718.xml

- ↑ Arlington Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development Historic Preservation Program, A Guide to the African American Heritage of Arlington County, Virginia (Arlington, 2016) 2d Ed. p. 32

- ↑ http://lindseybestebreurtje.org/arlingtonhistory/items/show/37

- ↑ NRIS p. 11, available at http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Cities/Lynchburg/118-5292_Kemper_Street_Industrial_HD_2008_NR_final.pdf

References

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934–35. OCLC 166632575.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. The Third Day at Gettysburg and Beyond. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-8078-4753-4.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

Further reading

- Hess, Earl J. Pickett's Charge–The Last Attack at Gettysburg. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8078-2648-5.

- Jamerson, Bruce F. Speakers and Clerks of the Virginia House of Delegates, 1776–2007. Richmond: Virginia House of Delegates, 1996. OCLC 182976627. Revised version of work by E. Griffith Dodson, first published in 1956.

- Stewart, George R. Pickett's Charge: A Microhistory of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959. ISBN 0-395-59772-2.

- Wert, Jeffry D. Gettysburg: Day Three. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-85914-9.

External links

- "James L. Kemper". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor James L. Kemper, 1874–1877 at The Library of Virginia

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gilbert C. Walker |

Governor of Virginia 1874–1878 |

Succeeded by Frederick W. M. Holliday |

| Preceded by Oscar M. Crutchfield |

Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates 1861–1863 |

Succeeded by Hugh W. Sheffey |